Conclusion

Scientific expertise and the politics of a ‘bad idea whose time has come’

Climate engineering has gained political traction in recent years not by mobilising positive visions of techno-scientific innovation, but by promising to respond to a dire crisis – that is, by tackling increasingly dangerous climate change. The magnitude of this crisis seems to suggest that we are simply out of options when it comes to deciding how we do or do not wish to address it. Climate engineering emerges in this historical moment as something to try, perhaps crazy, perhaps impossible, but potentially, the ‘least bad option we are going to have’.1

From this perspective, climate engineering seems to fit eerily well into the world that we live in today. It is a world that not only seems to be ridden with various globe-spanning problems, but that has also turned to scientific expertise for answers and solutions, for facts and fixes. As this book is being completed in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, notions of crisis, global problems, and ‘grand societal challenges’ have become increasingly central reference points for science-policy agendas.2 Such notions seem to provide an ever more critical context for scientific expertise to prove and reaffirm its relevance to society as a whole. Expectations for science in society are perhaps higher than at any point in recent history.

This is something of an odd twist, given that we supposedly also live in times of ‘post truth’, conspiracies and denialism. In fact, it seems as if precisely such notions of ‘post truth’ have supercharged scientific facts with political expectations. Despite readily rehearsed assertions within the social sciences that we are aware of the societal embeddedness of scientific expertise and the limits of techno-scientific control, scientific facts and expertise have witnessed a momentous comeback in recent years. As a kind of external, a-political, and therefore, universal problem-solving authority, the seemingly definite assertions of science mobilise hopes of clarity and unity in such divided times.

Against this backdrop, the career of climate engineering provides a crucial source of insight, and an important call for caution at that. In this concluding chapter, I want to suggest how this book’s analysis has not merely unpacked a highly controversial and somewhat curious debate in current climate policy contexts, but it has also shown how critically this debate speaks to the role of scientific expertise in contemporary politics.

(Re)Assembling the career of climate engineering

At its core, this book has unpacked the rich history of a ‘bad idea whose time has come’. Instead of essentialising climate engineering in its current form, the preceding chapters have sought to re-contextualise the making of this controversial governance object. The notion of the career of climate engineering has drawn attention to the historical contingency of what today is discussed as climate engineering. Retracing the career of climate engineering has helped to disentangle the various threads of scientific inquiry, national policy, and global geopolitical contexts that have, in hindsight, systematically brought us to the present point. It has enabled the turbulent trajectory of this ‘bad idea’ to be unpacked alongside its multiple temporalities, the diverse expert infrastructure that has assembled and stabilised it, and the epistemological categories which have defined climate engineering.

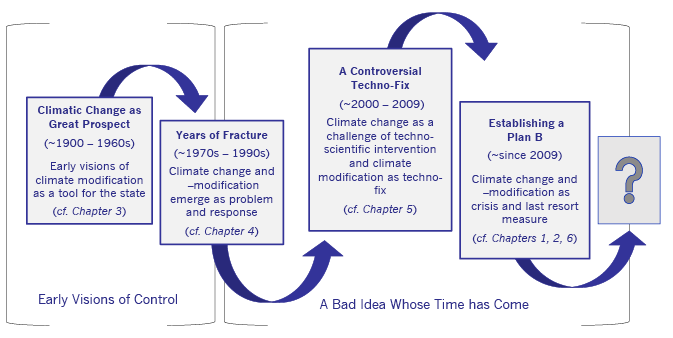

Before we dive into the broader significance of this analysis, let us briefly revisit some of its core findings. The book has revealed at least two defining historical threads (or even temporalities) in the career of climate engineering. Fig. 8.1 suggests how these two defining temporalities – suggested via the brackets – can be further differentiated into at least four distinct historical settings which define the career of climate engineering.

Fig. 8.1 The Career of Climate Engineering in US Policy

The first historical thread of this career of climate engineering is rooted in the history of climatology. In Chapter 2, we have seen how notions of targeted climate intervention have their historical origins in isolated projects of scientific curiosity at the turn of the twentieth century. Historical scholarship has illustrated in this context that before initial findings on the possibility of human impacts on climatic change were problematised, they provoked positive techno-scientific visions of the targeted modification and control of the climate. Climate change thus emerged as a ‘great prospect’. This dynamic then came into full swing with significant observational and modelling progress during the second half of the twentieth century.

During this time, a massive infrastructure of organisations, professionals, programs, and technical equipment stabilised the ‘quest for perfectly accurate machine forecasts and […] perfectly accurate data acquisition’.3 This infrastructure transformed the atmosphere into a subject that could not only be qualitatively described and mapped, but also ‘rendered calculable’, and therefore – this was the hope – controllable.4 This infrastructure provided the critical observational basis for assembling climatic change as a governance object that would lend itself to deliberate techno-scientific modification. Around the 1960s, we can observe an incremental shift in how visions of climate modification were problematised, when the distinction of deliberate and inadvertent climate modification appeared in scientific assessments. What would later be posited as problem and response, emerged as two sides of the same coin: as challenge and opportunity.

A second historical thread of the career of climate engineering was added around the 1970s through to the 1990s when the politicisation of climate change challenged carefully nurtured hopes of climate control and fractured established alliances between climate science and the state. In Chapter 4, we have seen how climate change emerged as an issue of environmental safeguarding; it was an issue that threatened to question the political and economic status quo. Only incrementally was climate engineering able to regain political traction. Alliances between climate science and the state now evolved around coming to grips with defining and understanding the problem of climate change. Climate engineering in this context appeared as a potential response measure to an increasingly urgent problem of global political significance. Finally, at the dawn of the new millennium, climate engineering moved from the margins of natural scientific assessments of climate change to the heart of fiercely contested congressional debates over how to tackle it best. By the end of its first decade, the concept had arrived in US climate policy as a challenge in its own right: climate engineering now took shape as the least evil in a hopeless situation.

This career of climate engineering thus corresponds to historically shifting modes of making sense of and problematising climatic change in relatively distinct historical settings. The boxes in Fig. 8.1 provide a strongly simplified overview. These historically particular modes of making sense of and problematising climatic change, also correspond to shifting configurations or alliances between climate science and the state. These alliances were forged by military and geopolitical challenges during the first half of the twentieth century by environmental challenges and the politicisation of climate change during the second half of the twentieth century, and by the notion of a climate emergency since the dawn of the new millennium. We have seen how the making of this ‘bad idea’ has mutually linked science and politics; how historically contingent visions of what is today discussed as climate engineering have provided a continuous, yet shape-shifting node in linking climate science and the state across different contexts and throughout different times; how climate engineering, in other words, can be understood as the result of highly specialised scientific and political processes, as well as their growing interdependence.

This outlook then questions some of the prominent dichotomies that have come to define the current debates over climate engineering. Particularly, it questions the narrative of the historical fracture that the recent rise of climate engineering has implied for existing climate policy agendas and established alliances between climate science and the state. A bold reading of this book’s account might even suggest that we tell this story the other way around, namely, as a story of how visions of climate engineering turned into explorations of anthropogenic climate change. Such a bold reading would suggest that it was not so much climate engineering that disrupted established climate change agendas, but rather that it was climate change that disrupted established climate engineering agendas and that it was the politicisation of anthropogenic climate change that fundamentally questioned established science-politics alliances around hopes of techno-scientific control.

More modestly, however, this book has shown that climate engineering has not emerged out of thin air. The book has embedded climate engineering in the larger history of efforts to understand and govern climatic change. Through the lens of this career of climate engineering, we get to see just how closely entwined these stories of efforts to understand and efforts to deliberately modify (even control) climatic change have been. This means that, as a response, climate engineering rests on a particular way of defining the issue at hand. This ‘bad idea’ grew out of a distinct mode of assembling climate change. Problem and response, in other words, are interrelated.

This does not, of course, delegitimise a critique of climate engineering, let alone render these measures unequivocally desirable. On the contrary, the analysis suggests that a meaningful engagement with (and critique of) climate engineering, must go further. It suggests that instead of singling out and essentialising climate engineering as the somewhat crazy, yet inevitable last resort measure, we must explore this interrelation between assembling and addressing, between understanding and governing climate change much more thoroughly. A meaningful engagement with climate engineering as a controversial policy measure essentially hinges on a thorough assessment of the modes of expert observations which have assembled it and the expert infrastructure which have stabilised this particular problem formulation. A meaningful critique of climate engineering cannot disregard the problematisation of climate change which these measures rest on and respond to. This is true even more so if we do in fact consider climate engineering as a ‘bad idea’ or as ‘barking mad’.5 The previous chapters suggest that it is high time to move beyond distinctions of good and bad when it comes to climate science and climate engineering and to instead unpack their joint histories and infrastructures. I want to make two points on the matter.

On pluralising expert observations

To begin with, the perspective on the career of climate engineering advanced in this book suggests why and how it might be productive to pluralise policy-relevant expert perspectives on climate change. It suggests the merit of diversifying expert modes of observing and assembling the issue of climatic change. By making this suggestion, the analysis speaks to a body of literature which has pointed out that more climate science does not in fact lead to more effective policy action. Despite the vast amounts of resources that climate policy programs have poured into understanding the mechanical, physical, and chemical grounds of anthropogenic climate change, there has been little progress in addressing the negative impacts of climate change for society and the environment.6 Recent accounts in environmental history go even further, suggesting that progress in our climatological understanding of global warming not only failed to spur mitigation of the issue, but – quite to the contrary – directly corresponded to a spectacular acceleration of the crisis. There is now more CO2 being emitted to the atmosphere on a daily basis than ever before in human history.7

How might we make sense of this? Why has this ever more differentiated picture of the climatological intricacies of global warming had so little effect on halting its causes? An obvious response to these questions is that, quite simply, understanding is not the same as acting, that knowing about an issue is not the same as doing something about it, and that, by extension, scientific facts and findings do not affect political action in any linear or targeted sense. Following this line of reasoning, science policy literature has diagnosed an oversupply of useless expertise, pointing to the irrelevance of the provided expertise to effectuate policy change.8 The authors find that a general mismatch between the provided expertise and the needs of political decision-makers provokes the systematic failure to generate ‘relevant and usable scientific information’ in this case of climate change.9 The scientists, put differently, follow a different logic in their work than the political decision-makers, and therefore, supply and demand of expertise are not balanced and need to be reconciled to ensure a better societal outcome to act on this issue.

I want to suggest that this book’s analysis of the career of climate engineering complements this diagnosis. Specifically, it aids in further differentiating the notion of what we consider as politically ‘relevant’ scientific expertise by emphasising the interrelation between science and politics in assembling and addressing societal problems.

Despite being framed as a ‘Plan B’, climate engineering evolved from persistent political efforts to cultivate and harness climatological expertise as a means to make climatic change politically legible and governable. Somewhat paradoxically, the rise of this ‘bad idea’ suggests how climatological modes of assembling the issue have proved politically effective as much as misleading in the sense that they suggested the possibility of their political control. We have seen how, over the years, expert committees and agencies have assembled the issue of anthropogenic climate change as an issue that concerns the understanding and governance of an exceedingly complex ‘climate system’, compounded of not only the atmosphere, but also the ocean, large ice-shields, such as sea ice or glaciers, the pedosphere, as well as the marine and terrestrial biospheres and many more parameters.10 The career of climate engineering suggests how this particular mode of observing climate change not only turned the issue into a challenge to utilise ever more precise scientific observation, measurement and prediction of a complex climatological system. But also, it demonstrates how this mode of observing the climate corresponded to and even directly fuelled hopes of being able to deliberately modify and control the parameters of this very system. Climate engineering, in this sense, emerged as a project of climatological cultivation and control. This case of climate engineering thus suggests that the issue of scientific expertise in climate policy is not so much useless, but, rather to the contrary: it involves a somewhat distorted overreliance on one particular expert mode of observation on the issue at hand. To put it bluntly, the career of climate engineering suggests just how consequential the political cultivation of climatological expertise has been.

This, of course, is not to say that the political consideration and support of climatological expertise, let alone the mere progress of climatology, single-mindedly led us to the prospect of climate engineering. However, it is to stress the complex interplay between science and politics in assembling and addressing societal problems. It is to emphasise that the history and particular trajectory of climate engineering is intimately linked to the history and particular trajectory of alliances between climate science and the state. Science and politics do not merely meet in this context as evidence base on the one hand, and decision-making authority on the other. Both are coupled at the upstream; that means, they are mutually constitutive in assembling societal problems and devising respective response measures. The question then is not merely one of more or less useful facts, but a question of what kinds of facts for what kinds of politics, and, vice versa, what kind of politics for what kind of facts.11

The turbulent trajectory of climate engineering reminds us that it matters how we choose to look at the issues of our time. It reinforces to us that we are precisely not out of options. If anything, this book’s account suggests we need to consider alternative, additional, and more diverse perspectives in making sense of and addressing the issue of climate change. While climate science is obviously essential to this endeavour, it can only solve part of the puzzle. To change course, it seems essential to broaden disciplinary vistas and avoid a kind of tunnel vision onto the climate ‘out there’. In this context, scholars from various disciplinary backgrounds have repeatedly emphasised the continued lack of social scientific perspectives within climate policy.

In the early 1990s, environmental scholars Peter Taylor and Frederick H. Buttel already began to ask, How do We Know We Have Global Environmental Problems? In this essay, the authors contrast the problem-defining authority of climatological expertise with the social precondition of the climate change challenge:

Of course, global change researchers know that climate change is a social problem, since it is through industrial production, transport and electrical generation systems and tropical deforestation that societies generate greenhouse gases. Nonetheless, it is physical change – the mechanical and inexorable greenhouse effect – that is invoked to promote policy responses and social change.12

This important observation continues to resound in more recent accounts of the potential role and importance of the social sciences and humanities in crafting meaningful climate change policy.13 Such accounts emphasise that climate change is not merely a biophysical process. They illustrate how climate change is an issue of social and power relations engraved in human infrastructures; it is an issue of how we live and sustain ourselves, how we work and commute, and it is an issue of international relations, economic systems, and political order. In his comprehensive account on The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming, Andreas Malm, for example, explores the critical role of labour relations in driving the issue of climate change. He writes that

Anthropogenic climate change – this is part of its very definition – has its roots outside the realm of temperature and precipitation, turtles and polar bears, inside a sphere of human praxis that could be summed up in one word as labour.14

The task, then, is not to explore the ways in which climate and climate change have defined history, but to explore how history has shaped climate: ‘in a warming world, causation runs, at least initially, from company to cloud’.15 To change course, in other words, it is essential to understand these kinds of drivers of climatic change, to explore more thoroughly how we ended up in this mess in the first place.

The funders of scientific research have also recognised the lack of social scientific perspectives on the problem of climate change. In its 2012 review of the government’s new ten-year strategic plan for the federal development of climate change expertise, the US National Research Council emphasised that the plan’s ‘proposed broadening […] to better integrate the social and ecological sciences’ would be ‘essential for […] understanding and responding to global change’. 16 It openly criticised that the responsible agencies ‘have insufficient expertise in these domains and lack clear mandates to develop the needed science’.17

Almost a decade later, however, the issue seems to persist. Pluralising expert modes of observing and assembling climate change as a societal problem would thus necessitate a more consistent and radical mode of interdisciplinarity. It cannot merely imply charging the social sciences and humanities with illuminating the consequences of techno-scientific interventions. Chapter 6 has suggested that the situation is much more complicated than that. A change of perspective would require inviting competing – even conflicting – modes of observation. It would imply strengthening diverging modes of making sense of societal issues. It would require not only hunting for ‘facts’ but allowing for ambiguity and complexity.

From scientific conspiracies, cliques, and mafias to matched struggles

The perspective on the career of climate engineering provided by this book suggests a second area where critical attention is required to move beyond simplistic distinctions between good and bad when it comes to climate science and climate engineering – accounts that reduce climate engineering to the concerted agenda of individual scientists. The preceding chapters have illustrated that neither the discovery of global warming as a societal problem of global political significance, nor the rise of climate engineering as a controversial ‘risk management strategy’18 for tackling this issue are merely the result of a scientific conspiracy, sinister or otherwise. Visions to technically modify, deliberately alter, or engineer the climate have not been forced onto the political agenda in an orchestrated plot by a group of scientific experts. Rather, the previous chapters have suggested that scientific expertise has to be understood as relational. Who gets to ‘speak’ to politics, who appears as a scientific spokesperson, which experts and what kind of expertise are heard by policymakers – and thus define political agendas – depends just as much on political selection processes as on the experts themselves. To be politically relevant, that is, to bear in one way or another on political processes, scientific expertise must resonate in and be internalised by the political system.

Rather than overemphasising the relevance of individual scientists and their personal agenda in pushing policy programs and forcing their perspectives onto the political realm, the book has drawn our attention to the settings which have channelled these experts onto the political stage. It has shed light on the expert infrastructure, that is, the channels and pathways, arenas and corridors, effectively structuring alliances between climate science and the state, and thus giving these alliances their particular form and shape. Therefore, this perspective on the career of climate engineering not only helps make sense of the recent rise of this ‘bad idea whose time has come’ by opening our gaze onto this multi-layered expert infrastructure, but the analysis also speaks more broadly to science policy studies and the study of expertise in politics.

By following the career of climate engineering as it has defined science-state alliances in different contexts and at different times, we gain a comparative perspective on the various settings defining these alliances and linking scientific expertise to politics. The general insight from mapping this climate engineering expert infrastructure is that the political relevance of scientific expertise can be differentiated along the particular settings which connect it to the policy process. Put differently, the various settings which channel scientific expertise to politics correspond to respectively distinct roles of scientific expertise in shaping the politics of climate engineering. There are congressional expert witnesses serving as ‘masked agenda setters’, pushing a controversial measure seemingly incidentally onto the congressional agenda before policymakers take an official stance on the issue (see Chapter 5). There are also various settings in which policymakers invite or commission different forms of ‘staged advice’, defining the issue at stake as a ‘matter of facts’ (see Chapters 2, 4 and 6), and there are expert organisations and programs within the federal bureaucracy that institutionalise the political cultivation of issue-relevant expertise within the political realm (see Chapters 2 and 6).

Two such expert settings, in particular, appear to be important components of the climate engineering expert infrastructure. The first expert setting concerns what I suggest we call arenas of ‘staged advice’. We have seen how these arenas provide the relevant context for linking scientific expertise from beyond the federal infrastructure to the political realm. This is an expert setting which indeed made scientists into a kind of spokespeople for assembling policy issues. Both the politicisation of climate change during the 1980s, as well as the politicisation of climate engineering during the early 2000s, became visible to the public primarily by means of a highly visible group of experts who were ‘raising the alarm’19 and defining the relevant ‘facts’ about these issues respectively. The fact that the literature has somewhat ironically described these experts as conspiracies, cliques, or mafias is instructive in this context but not for blaming or praising the political stance of these individual scientists and experts. Instead, these metaphors are telling as they suggest an underlying logic, an implicit script or system that guides the concerted agenda of these scientific experts and explains their visibility and impact in shaping the political agenda.

Chapters 2 and 6 speak to this assumption by unpacking just how carefully these arenas of staged advice are orchestrated. The chapters suggest that the political system has developed two forms of such staged advice that serve to determine politically relevant experts and channel scientific spokespeople onto the political stage, namely scientific assessments and legislative inquiries. In the context of climate change, as well as climate engineering, scientific experts shaped the political agenda on these issues by testifying before Congress and contributing to scientific assessment reports. Both forms of staged advice institutionalise the selection of politically relevant scientific expertise differently. Both embody different modes of linking scientific to political observations. Scientific assessments seek to harvest scientific excellence for policy questions. While policymakers may ask the questions (and commission or approve the assessments), the assessment bodies strive to institutionalise criteria of scientific quality in the selection of viable experts and the production of these assessments. Scientific assessments and their respective lists of experts thus document how the politicisation of visions to modify and intervene in the global climate have historically connected to inner-scientific structures of disciplinary distinctions, research schools and programs, methodological and conceptual outlooks.

Legislative inquiries, in contrast, give much more leeway to the policymakers and committees in selecting who qualifies as a relevant expert. This selection process is precisely not specialised on the selection of scientific experts.20 It follows additional criteria other than scientific output and academic reputation, which makes the prominent status of scientists (even academic scientists) as spokespeople for the politicisation of climate change and climate engineering all the more noteworthy. What is more, in the politicisation of climate change as well as climate engineering, the experts testifying before Congress were often also quite visible and outspoken on these issues in the media. The exact connection between these two contexts of appearance would have to be studied systematically in future research. Does political expert status explain media visibility or does media visibility explain political expert status? Aside from scientific and technical credibility and media appearances, the literature points to a plurality of selection criteria that are at play in this context.21

The second critical component of the climate engineering expert infrastructure is an expert setting that I suggested we call ‘science for national needs’. We have seen how, building on the invitation of staged advice, the political system internalises scientific expert modes of observation into the federal infrastructure. The state thus stabilises and institutionalises a particular gaze on the issue at hand, seeking to actively steer or cultivate politically relevant expertise within its own infrastructure. This expert setting thus does not channel external expertise towards the political system, but instead cultivates relevant expertise within its own bounds.

Through the lens of this expert infrastructure, climate engineering hardly appears as something controversial and new. From this angle, the rise of this ‘bad idea’ instead emerges as rooted in the organisations and programs that have defined the US political problematisation of climate change for decades. This includes agencies such as the IPCC, central agencies of the US Global Change Research Program (USGCRP), such as NASA, NOAA, EPA, DOE, as well as WHOI or LLNL. Many of these organisations have been established even before anthropogenic climate change had even been politicised as an issue in its own right. They essentially represent the institutionalisation of atmospheric and oceanographic research within the federal bureaucracy.

Outlook: From following the actors to following the problems?

This book presented an analysis of the role of scientific experts and expertise in politics by approaching the matter somewhat inversely. Instead of merely following the experts, it placed an object of expert work, namely climate engineering, front and centre. Connecting to the basic tenet of ‘following the actors’, it sought to give climate engineering a life of its own.22 The book followed climate engineering through shifting historical contexts, through diverse expert settings, and different expert modes of observation to get a sense of how it became what it is today. In other words, it sought to understand how it became assembled as a controversial policy tool to fight the problem of anthropogenic climate change.

As global problems and societal challenges become increasingly important reference points in determining the societal status of science and the political relevance of scientific expertise, this approach promises to provide a differentiated picture of the complex interplay of science and politics as two distinct, yet increasingly interdependent, realms of society. I want to end by reflecting on the potential merit of this approach for making sense of the status of science in society – not only as an academic enterprise within science studies, but more generally, to suggest how it might help us grapple with the current situation we find ourselves in, which is beset by so many often overlapping global challenges, as laid out at the beginning of this chapter.

Approaching the science-politics interrelation via the historical trajectories or ‘careers’ of societal problems sheds light on the contingent and reflexive nature of this interplay. The analysis in this book demonstrates that climate engineering is neither the result of a simple steering (politics → science), nor the result of an informing or advisory relationship (science → politics). Instead, it emerges precisely from the mutual observation of both societal realms. This approach, then, suggests how the interrelation between science and politics amounts to more than the sum of its parts. Giving climate engineering a life of its own in this sense means considering the inherently dynamic trajectory that this object of expertise unfolded.

We saw how this reflexive relation is written into a diverse infrastructure of expert settings and various kinds of expertise that emerge at the interface of science and politics, and that have given climate engineering its particular shape over the years. Following the career of climate engineering in this sense sheds light on how settings of expert policy advice complement networks of epistemic communities or independent scientific agencies in linking science and politics. At the same time, it embeds this expert infrastructure and these forms of expertise in their particular historical context. The witness lists and expert assessments, and the programs and missions of expert agencies, for example, document how the political problematisation of climatic change and intervention has shifted over the years. This approach thus combines an interest in overarching structures that define the interrelation of science and politics across time and space with an interest in the historical genesis and evolution of these very structures. Finally, following this career of climate engineering suggests how, vice versa, this object of expertise bears consequences for science and politics respectively. This is a theme which has been less thoroughly explored in this book and needs to be subject to future research. The book can only hint at how climate engineering fosters changes in inner-scientific structures and political landscapes, how different visions of modifying and intervening in the global climate generate new publication networks, research communities, and gradually also formal scientific programs, how it gives rise to new political constituencies regarding climate change, and how it formulates new political categories.

Therefore, the analytical approach of this book might also help us make sense of the status of science in society today. It may help us grapple with the crisis narrative that is so often attached to major contemporary global challenges – to return to the themes with which this chapter and the book as a whole began. To put it bluntly, the story that this book tells suggests that we are precisely not out of options. Instead, the perspective that this analysis has opened up encourages a more productive way of engaging with science in society. It suggests a more productive vision for the role and status of science in addressing the issues of our time.

In shedding light on the career of climate engineering, the book’s analysis suggests that advancing scientific expertise in the name of emergency or crisis is unproductive if it serves to suggest a lack of agency in the face of the issues that societies face today. It is unproductive, in other words, if it is mobilised as a means of closing down democratic dispute or options of engagement and political controversy. We have seen that scientific expertise is not external to the issues that it promises to tackle. Instead, the process of making sense of societal problems and devising response measures, of assembling and addressing governance objects, is reflexively linked. Scientific expertise might seem difficult to argue with. This book suggests that it shouldn’t be. Mobilising scientific expertise in the name of tackling crises and societal issues can be productive precisely if it serves to foster reflexivity and a change of direction. Instead of emphasising factual constraints and closing down possible futures, it should be mobilised to diversify them.

Promoting climate engineering as a necessary evil, then, is not only problematic because it proposes a narrative of scientific control in the face of the dangers of climate change. It is also actively misleading if it serves to deflect attention away from an understanding of how we got here, via a rich and multi-layered history, involving the cultivated structures that have systematically brought forth this ‘bad idea whose time has come’. Taking this rich history of climate engineering seriously is also essential for challenging the narrative of a future without choices. As I suggested in the introduction, as much as politics might sometimes allude to external urgencies that force our hands, climate engineering is not infused into the political process by the external urgency of dangerous climate change. It arrived here from within: this particular vision of making sense of and responding to climatic change has a historical legacy and system.