2

Sharing Heritage Through Friction

Fig. 2.0 Old construction secured with concrete bricks, 2008, Osu, Ghana.

Cultural Encounters in the Hot Colonies

It is important to emphasize that these projects are not undertaken to show how Denmark once acted in the wider world. Neither colonization and foreign politics nor a distant dream of national grandeur are the focus of the projects – the focus is on the cultural encounter.1

With these introductory words, the two coordinators of the Trankebar Initiative and the Ghana Initiative explained the National Museum of Denmark’s engagements in what the former Director referred to as ‘the hot colonies’. More specifically, these engagements translated into initial steps to renovate a former Governor’s house in India and reconstruct a former plantation named Frederiksgave in Ghana. If successful, they would later be followed up by further projects in the two countries.2 By focusing on the so-called ‘cultural encounter’, the authors were accommodating a criticism that was rarely aired in the museum but which was, every now and then, talked about among the Danes involved in the projects, namely the criticism of creating projects that potentially revived a past in which the Danish nation’s grandiose international role was in focus. At one point, this criticism was formulated in a song for an office Christmas party written by a museum employee who was not a part of the initiatives. The song was a rewriting of a well-known children’s lullaby which during the 2000s was criticised for being racist because of a line that has a baby elephant using a ‘negro boy as a rattle’. The rewritten song had four verses, one introductory and one for each of Denmark’s ‘hot colonies’ (i.e. parts of India, of Ghana and the Virgin Islands). The photocopied song was distributed at the Christmas party, and within minutes we were all standing, slightly intoxicated, with the sheet in our hands, ready to sing.3 The introduction and verse about Ghana went as follows:

Now stars are lit in the blue skies

and in the countries near by Equator,

And what a thrill to think about

when Denmark was a coloniser.

So dream of those days when we were there

With helmets, forts and frigates.

But the grandeur of the past is near now,

And our flag Dannebrog4 waves again.

Now whites are sent to Ghana’s coast,

Once again to build plantations,

Where blacks are working like anything

To create for us affective tableaux.

And in the midst of the jungle where nothing is up,

Where there is practically nothing to do,

Of stones and clay a phoenix bird rises,

The Danish-most house Frederiksgave

In a bitingly satirical way, the song jokingly pointed to the grandiose nationalistic and neo-colonialist perspective potentially embedded in the museum’s hot colonies initiatives. By pointing to a lost Danish past that was now to be revived by the Frederiksgave project and other similar projects, it echoed – humorously – the nationalistic voices also raised in one of the books about the old ‘tropical colonies’ written during World War Two and referred to in Chapter One. In general, people seemed amused to be singing the song at the Christmas party, but I never heard it mentioned again after the collective singing by all the museum’s employees in 2006. If the grandiose nationalistic perspective was discussed by the Frederiksgave project planners, it was from angles other than the satirical. The hot colonies held histories that were delicate and nothing that Denmark could be proud of, as one person from the museum said, but the project planners agreed that these stories of hurt were not to be blamed on present-day Denmark; the Danish involvement on the West African coast certainly presents a difficult heritage, but the project planners did not project this embarrassing legacy onto present-day Danes. This opinion was shared by the people I talked to in Ghana, and a similar statement was made by the Director of the National Museum in an interview with a Danish newspaper.5 Needless to say, however, such a common understanding of not blaming present-day Danish people for past atrocities complicated considerably the attempts to tell the history of ‘our common past’ in a straightforward and homogeneous way, as I will explore in the following chapters. The song, and a few critical voices, raised a criticism that the Director of the Museum had already referred to on previous occasions. And with a consequent change of focus, the project coordinators of ‘The Trankebar Initiative’ and ‘The Ghana Initiative’ stated that, instead of ‘colonisation’ or ‘foreign politics’, the two projects would focus on the key term of ‘cultural encounter’. The coordinators further specified that

The Danish presence in the regions concerned brought about encounters between completely different cultures, and in our times, too, cultural encounters take place, even if on different terms. It is important that the cultural encounters are seen and appraised not only from a Danish point of view, but also from local perspectives. What images of the strangers from the far north do people in these former colonies have, and what were the cultural, economic and social consequences of the Danish presence – then and now?6

In this chapter, I will explore how people – primarily from the Danish National Museum – conceptualised, designed and framed the Frederiksgave project and the plans for new projects in Ghana. I will offer a reading of how the Frederiksgave project was visualised and presented as a cultural encounter between equal partners, making it appear to be a heritage project beyond the colonial encounter in a very particular sense. Implied in the project vision, it seems, was an idea that we are all past being responsible for or victims of colonial wrongs. In our symmetric present, accordingly, science and history can be cast as neutral and evenly accessible to all, provided we inform people properly about their findings. How did the museum’s ideal of a symmetric cultural encounter, in which ‘local perspectives’ are equally important to Danish perspectives, relate to ideas about a common history also present in the project? In what ways were Denmark and Ghana seen as sharing a past? How was commonness articulated in the design and realisation of the Frederiksgave project, and in what ways were the Ghanaian collaborators expected to be involved? And, more generally, what kind of objects of knowledge does it take to even conceive of the heritage initiative as a cultural encounter? This chapter explores these questions by looking closely at a series of encounters that took place within the Frederiksgave project.

My choice to start this chapter with the above two quotes is, of course, deliberate. Together, the quotes immediately raise the question of what is meant by ‘culture’ – a highly contested term within anthropology7– and also ‘encounter’. As I will substantiate throughout the book, the concept of encounter is crucial because it was central to the Frederiksgave project, and also because it structures whichever entities can be foregrounded as things that meet. The quotes give us a hint. ‘Denmark’ and ‘Danish’ are both mentioned as being one part of an encounter between ‘completely different cultures’. Concerning Danish culture, the authors thereby partly conflate the notions of culture and the nation state, denying space to other cultures qualified as being ‘local’, that is, in the etymological meaning of being limited to a particular place but not necessarily bound to a nation. Such an understanding of culture might seem straightforward from the perspective of a national museum accustomed to classifying and thinking about its purpose according to the Danish nation state.8 The quotes from the two coordinators of the National Museum’s initiatives presented above emphasise the fact that continuous encounters between different cultures need to be seen and evaluated from more than one perspective; in their case, not only from a Danish perspective. The other side of the encounter, i.e. how the ‘locals’ view the Danes, is presented as a necessary part of the equation. The idea of switching between these two cultural perspectives illustrates the presumed existence of a sort of meta-perspective, an abstract neutral space that can collect and structure the information on how different cultures ‘see and appraise’ the world and each other. In order to study ‘what images’ we (as in the Danes) have of them (as in the locals) and how they see ‘the strangers from the far north’ one would thus have to externalise oneself from one’s cultural perspective, take the point of view of the other culture’s perspective and, finally, abstract oneself from both cultures in question by presenting what is thought to be ‘one culture’s view of the other’ – an abstraction of or meta-perspective on the observations collected. As we shall see, in the design of the Frederiksgave project this abstracted perspective turned out to be a mix of cultural relativism and indisputable and impartial science – which in the actual realisation of the heritage project turned out to be a difficult position to speak from with any clear voice. The two coordinators’ statements require a sort of empathetic movement that falls into three steps of, metaphorically speaking, undressing (take off one’s own cultural dress), re-dressing (putting on the other culture’s dress) and, finally, dressing in an authoritative and supposedly non-distinct white coat in order to speak from a neutral position.9 Even though most anthropologists have disputed and long dismissed any idea of speaking from a neutral position, there seems to me to be a remnant of this vision in the relativist stance, with its implied external point of view, allegedly enabling a cultural expert to speak and translate on behalf of the (other) culture in question. It should be added that this authority may not be recognised as such, because the notion of cultures here implied is rarely queried in cultural relativism – there is in a sense nothing to exert authority over; rather, cultures appear as universal givens, beyond discussion – an understanding that has been strongly challenged, perhaps most famously in the book ‘Writing Culture’.10 Hence, from a cultural relativist perspective, the (cultural, historical…) scientist seems endowed with a kind of authority without any source, an authority from nowhere or everywhere, which reflects the idea that authority is gained by abstracting the perspective.11

In Chapter One, I mentioned the widely held view that no heritage projects are ever devoid of particular perspectives on the past, a view that has given rise to many analyses of the contested nature of heritage and the attendant negotiations of power involved in reconstruction. Here, interestingly, the exertion of authority takes the form of ideally equalising the potentially conflicting points of view by assuming the viewpoint of an allegedly uniform template, geared to accommodate differences of content without the form (Culture or History, as we shall further explore, with capitals) of these being shaken. The relativist idea of cultures as parallels within a given pattern, and as identifiable regardless of perspective, is discernible in the fact that what is constant in the coordinators’ statement is the very notion of cultures; what changes is what these cultures consist of. One can see how Danes involved in the project were supposed not only to visualise the encounter from a ‘Danish’ perspective but also to attempt to extract themselves from their Danishness and enter – or at least look at – the ‘completely different culture’. Interestingly, as we shall further explore, this extraction entails a step up to an abstracted sphere provided and guaranteed by the National Museum – which, paradoxically, then figures as a common universal platform rather than a particular national figure. By virtue of its relativist neutral stance, the National Museum supposedly has universality on its side. To create the symmetry and equality needed to imagine the heritage work as an equal cultural encounter between universally given cultures, the Danes involved in the project were supposed to ‘see and appraise’ how the Ghanaians involved saw not only the cultural encounter itself but also the Danes, described as ‘strangers from the far north’. An appraisal of both sides of the equation necessitates abstraction. One might therefore ask whether this externalisation of perspective is a necessary prerequisite for the project-makers in order to reach the desired commonness. And what happens to the encounter if it is only to be reached through a move to an externalised, abstracted and universal space? In this chapter, I will explore these attempted movements to the universal (and thus seemingly anonymous and apolitical) realm to discuss a potential implicit contradiction in the Frederiksgave project design, between the abstracted neutral universality of cultural relativism and the actual encounters of the project work.

Protecting Remains: ‘The least we can do’

In Denmark, one of the biggest newspapers wrote in a sub-headline: ‘Experts from the National Museum have come to Ghana to save the ruins of Danish colonial times on the former Gold Coast’.12 Using a well-known rhetorical trick to stress the dynamism of the initiators, the article began by opposing the sub-headline with the following: ‘Accompanied by the lazy waves against the Gold Coast, and enveloped by the curiosity of friendly locals, experts from the National Museum are surveying the remnants of…’.13 Seemingly, nothing would be done in the country, repeatedly being lapped by the lazy waves hitting the coastline, if it were not for the initiators from the Danish National Museum. By countering the invading nature, in what could be termed a natural encounter, the initiators of the Frederiksgave project were acting heroically on behalf of history, according to the journalist. Indeed, such natural forces were recognised as acting directly on the former Danish objects, as we shall see.

Fort Prindsensten, the easternmost former Danish fort, painfully reminded the people from the National Museum of this fight against time and the necessity of taking action. The sea had been slowly advancing since the beginning of the twentieth century, and by the 1990s, three-quarters of the fort had been eroded.

Fig. 2.1 Fort Prindsensten from the seaside, 2008, Keta, Ghana.

Only following the most recent serious flooding in the 1980s had foreign donors sponsored a billion-dollar sea defence to protect the city of Keta. The architect hired to find Danish traces in Ghana was left with only one curtain wall of Prindsensten and a few illustrations of the fort drawn by expatriate Danes in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Tirelessly and with enthusiasm, I helped the Danish architect trace photos of the fort at the public office, at the Chief’s office and at various private households in order to supplement our knowledge about the otherwise disappearing fort. People enjoyed showing us their photos of various important moments in their lives. And, indeed, it was exciting to be invited to look at people’s photo albums and see all the connections and travels they and their relatives had made. In contrast to the lack of interest in the (histories of the) Prindsensten Fort, the personal histories entailed in the photo albums were clearly of high priority. Having looked at several faded, dusty and treasured photos, we found a handful of old photos depicting various parts of the fort. Bent over the photos, we meticulously studied details and accompanied our discoveries with exclamations of: ‘It’s fantastic!’, ‘Wow’, ‘Oh, look there’s also this feature’, ‘Yeah, you’re right, there used to be a door there’, ‘Oh, it would have been even better if they’d taken a photo from the other side as well’, etc. With the aid of a magnifying glass, the photos were compared with the physical remains in minute detail.

Over the last couple of years, I have spent time with several Danish architects in Ghana, learning the importance of one of their basic activities, namely surveying buildings. As an alternative to rescuing the common heritage in time, it was repeatedly suggested that this surveying was ‘the least we can do’ with regard to the Danish-built forts and buildings along the Ghanaian coast. The Danish architects thus echoed what the museum director had advocated a few years before the Frederiksgave project was launched. In an interview with one of the most popular newspapers in Denmark, the director had been invited to discuss ‘general education’.14 Although he made it clear that bildung did not come from the National Museum or other cultural institutions, he was nevertheless scarcely able to imagine what generally educated people would do without the National Museum. Having stressed the importance of the family in creating educated people, he continued:

that we [the National Museum] have an obligation because general education [bildung] and personal identity simply cannot exist without historical awareness. This does not necessarily imply that you must know the list of kings. But at least it is important that you have some sense of the sequence of events, and of the frame of reference. Because the reference unites us and provides a shared interpretation and understanding.15

Here the director wanted to underscore the importance of an historical awareness among Danes, an awareness that, even minimally defined, could at least frame events and give a sense of sequence. As such, the director argued, historical awareness was vital and a prerequisite to having a personal identity and general education/bildung. This is a view that he shared with the Minister of Culture, who, in an interview with another major Danish newspaper, related rootlessness to not knowing one’s history.16 In his critique of the tendency to historicise life and thereby risk mummifying it, Nietzsche suggests that we should ‘serve history only so far as it serves life’.17 The question is, then, which forms of life does the history produced in the Frederiksgave project serve?

Soon after the Frederiksgave project – the museum’s first initiative in Ghana – was launched, the director said, ‘We approach these foreign sites with a bit of humility. But, after all, we do think that we share a common interest in uncovering the past that we have in common.’18 Here the director again argues for the importance of an historical awareness and of having a ‘common interest’ in a shared past, but this time not only to a Danish audience but also, indirectly, to the people with whom we share a past. It is interesting to note the small words ‘after all’ contrasting the ‘bit of humility’ with which the Danes should approach these sites. Even though the Danes from the National Museum are humble, ‘after all’, we need to ‘uncover the past we share’ and, in the words chosen two years earlier, the need for an ‘historical awareness’ in order to have a ‘personal identity’ is expanded to include the Ghanaian population. The unveiling of the shared past was quite simply seen to be of common universal interest. To the Director of the National Museum, a museum has to approach these foreign sites with a little humility but, ‘after all’, history must be brought to light. And uncovering our common past entails countering the invasion of nature before it is too late; rescuing what remains is ‘the least we can do’. In other words, the National Museum here portrayed itself as giving ‘a helping hand’, as a key person from the museum framed it, to the supposedly innocent activity of preserving a heritage of universal value. Likewise, and in response to the different histories told at the Frederiksgave site, the Danish coordinator expressed this need on several occasions: ‘We have to insist on bringing to light the true history – we have to dig our heels in’. In light of the director’s statement about the need to know one’s past, the coordinator’s stake seems obvious; of course ‘we have to dig our heels in’ – our very identity is at risk. In an interview with a Danish postgraduate student of history in the spring of 2010, the Danish coordinator was confronted with accounts from the ‘local guides’ that did not coincide with or communicate the story told on official posters at the Frederiksgave site – a ‘problem’ that was also encountered at the forts and castles. In response, the coordinator explained: ‘One cannot blame them [the guides] for telling the story that brings more money, yet this [blame them] is what we must do anyway!’19 The problem that the coordinator was alluding to was the so-called ‘wrong story’ that connected the Frederiksgave plantation to the transatlantic slave trade, as told by some of the guides at the Frederiksgave site – an issue I will return to in Chapter Five. The issue here is that the apparent dissonance in the heritage project is seen as having to be resolved. It becomes a matter of trying to make the Ghanaian guides play their part in the common project of informing about the shared history while not blaming (yet in fact, blaming) them for not doing so. It is not that the coordinator does not understand the use of the dramatic – and potentially lucrative – history of transatlantic slave trade; the problem is that the guides somehow betray the project that is regarded as of completely common interest. Collaboration becomes a matter of speaking with one voice, namely that of history. The coordinator was also alluding to some of the stories told by guides at the forts and castles along the coast, who at times portrayed Europeans as unscrupulous robbers who stole Africans and shipped them to a life in slavery. When people from the National Museum and I heard such stories during our visits to the forts and castles, we agreed among ourselves that, true, the Europeans may have been unscrupulous in even thinking about dealing in slaves, but the slaves were traded with willing African kingdoms; they were not stolen. Importantly, this seemingly vital difference was affirmed by an appeal to indisputable historical records. According to the Danish coordinator, these wrong and hateful narrations that contradicted historical evidence should not be accepted. What is interesting and perhaps paradoxical here is that the reason for this apparent need to set the historical record straight by striving to allow the heritage sites to tell only one story seems to be a ‘democratic’ notion of equal access to historical knowledge; if we allow more stories to flourish, reconciliation, curiously, is threatened, as expressed by the Danish coordinator:

From a phenomenological point of view, should we not leave these narratives be? On the other hand this creates reversed racism. Reconciliation is important and we should drag history back into the light. The Ghanaians do not want to talk about personal matters, but are willing to talk about the general history. We cannot create unity by ‘hate stories’. This is why we have to dig our heel in.20

There seems to be only one story that should be told at the site, namely History (with capital H). It is a history that, just as the director noted, lies slumbering, waiting to be discovered as being of common interest. The commonness of the heritage is therefore found in objective evidence and must result in the joint fight against wrong-tellers of hate-histories (and against the expanding invasive nature). In this way, I suggest, history in the singular – as bildung extended to all – undermines or pre-empts the practical encounter by attempting to make the ‘wrong stories disappear’. Because there is only one history, with its assumed shared importance that is already universal and unquestionable, it becomes the shared and neutral responsibility of all involved in the project to communicate just that. The other stories told by the guides at the sites are false and threaten to erode historical awareness and identity – understood and presented as being uniformly based on and in accordance with archival records, archaeological excavations and architectural examination – and should be eliminated by ‘digging one’s heels in’. The project self-identified as naturally speaking for a total ‘human community’, ideally formed by historical bildung. It was not a matter of representing different communities’ points of view. In a sense, one might say that within the Ghana Initiative’s discourse there are no relevant local points of view. For all the praise for cultural encounter, the only encounter which is really allowed to produce changed conditions is the meeting with the expanding and destructive natural world (the rising sea, the growing forest, etc.) or the expanding capital city that threatens to obliterate history. On both accounts, the National Museum is the perfect objective custodian.

In the opening to this chapter, I remarked on how cultural relativism pervaded the ideas of cultural encounters in the Frederiksgave project and demanded a sort of meta-perspective from where one could see and appraise encounters between given cultural entities. Likewise, the quotations above can be seen to communicate an understanding of history that demands a sort of non-situated perspective – a perspective beyond the messiness of everyday life, beyond economic temptations and racial delusions, and beyond hate (which were the concerns of the coordinator). In other words, this perspective stresses a universal history that is, unless the National Museum interferes, under threat from the encroaching natural world, growing urbanisation and cunning wrong-tellers. This universal history should, with the help of the National Museum of Denmark uncovering it, inform about the past independently of economic interests. Moreover, by ‘digging one’s heels in’, this uncovering should bring about reconciliation – which is apparently an automatic result of dragging history into the light – and ensure that no ‘hate-histories’ are told. The truth demands action, not so much as a human or national ‘we’, but as a meta-agent talking on behalf of history. This produces a paradoxical figure of an encounter without any encounter, since the truth only has one side. One might say that it is ‘the heel’ that has to dig in ‘the heel’.

To sum up so far, we see the Frederiksgave project design entailing both a symmetrical encounter between different given cultures (no foreign politics or colonial legacy) and a view of a ‘now’ encountering a common universal history of equal importance to all, which we must protect from erosion whether by nature, modernity or by wrong-telling. What is central here is not just the glossing over of different perspectives by the appeal to a seemingly neutral historical science. Importantly, both of these ideas of encounter also belittle the generative friction out of which new entities are produced in a contact zone. Both notions of encounter in the Frederiksgave project (i.e. between equal but different cultures and between ‘now’ and common history) invoke claims to universal entities, all the while obscuring that these entities are made within the very same movement in which they are voiced. Let us take an even closer look at these paradoxical and simultaneously relativising and universalising manoeuvres.

Asking how ‘the universality of Nature operates in a world of friction’,21 Tsing examines the development of botany as a universalising science. Such an examination, I argue, could be analogous to an understanding of history as a universalising science, as presented above. I thus ask the same question, exchanging the word History for Nature, to explore the universality of history in a world of friction. But first I must digress into botany as it was developed in Europe in the heyday of the Enlightenment, according to Tsing. Being interested in analysing the movement through which singular observations relate to generalisations, Tsing explores the development of the European botanical tradition. Since the Middle Ages, she argues, this tradition has tried to create singular global systems that make it possible to understand and classify the empirical diversity of the universal Nature.22 The famous Swedish botanist Carl Linné’s celebrated book Systema Naturae is, as the title indicates, just such an attempt to create a classificatory system with a global reach; with this book, he wanted to create an overarching system for nature that was useful and applicable anywhere in the world. Tsing argues that the effect of Linné’s method is that the system becomes the primary object of botanical knowledge, while the multifarious flora that comprise it are reduced to data.23 Having first discovered such a system, botany then becomes a matter of pure collection, of collecting data that can be put into the system; each plant, or species, to use Linné’s vocabulary, has a place and, just as important, rooms are left open for as yet undiscovered species. The species are the parts or entities that are filled into the whole system, which pre-exists its parts. Linné’s universal system produces a natural distance between system and singular observations – an external relation between system and data. The development of botany, Tsing argues, can be seen as an index of how analyses use generalisations that aspire to a universal system, as in Linné’s case, or are conceptualised along more humble lines, i.e. by providing generalisations that do not aspire to universality. Tsing stresses that making generalisations is something that we all do all the time, and is not normatively bad. Generalisations are a particular way of dealing with difference and similarity and, more particularly, how difference and similarity are set. Making generalisations involves what Tsing analytically calls ‘axioms of unity’24 – an analytical synonym for generalisations. Axioms of unity are, as the name suggests, what unite otherwise dissimilar units and make their unity or relationship appear evident. In order to succeed, the unity must pre-exist the particulars. For instance, as Tsing writes, before uniting apples and pears, one needs the general category of fruit. The difference between apples and pears must recede into the background in order to foreground the relationship of similarity, generalised as fruit. By pre-determining the singular parts, the axiom of unity makes it possible to collect and order different singularities/particulars into generalisations, just as in the case of the apples and pears the generalisation of fruit demands that incompatible singulars be made compatible. Even the smallest conjunction among otherwise incompatible units is promoted to a unification. The abovementioned conjunction between apples and pears creates the generalisation of fruit by backgrounding their differences and foregrounding their similarities – one could say that they need to collaborate on their sameness by backgrounding their differences. There needs to be some shared agreement about the structuring of sameness and difference, and the conjunction legitimates the generalisations it produces. Or in Tsing’s words:

What is most striking to me about these two features of generalization is the way they cover each other up. The specificity of collaborations is erased by pre-established unity; the a priori status of unity is denied by turning to its instantiation in collaborations.25

Clearly, the two movements create a circular argument. On the one hand, the generalisations pre-exist the particular instances but, on the other, the particular instances create legitimacy for the generalisations. As a classical circular argument, the two movements need each other while at the same time covering each other up. In order not to naturalise the units and systems that the generalisations operate with, thus letting the circular argument affirm itself endlessly, we need to pay attention to the fact that the axioms of unity (and thereby the particulars and the generalisations) are products of collaborative processes. As such, the axioms are collaboratively accomplished figurations. The system of nature discovered by Linné is, then, a particular figure. If axioms of unity, then, are to be explored as creations, what is the generalising principle and what are its parts, its singular instances? In other words, what makes the axiom of unity work? Or, in relation to the question that has continuously guided me during my fieldwork and in this chapter, where should one position oneself in order to make the generalisation of a universal shared history and common past work in the Frederiksgave project? How is this generalisation accomplished in the project?

Juxtaposing accounts from the project with Tsing’s work, my suggestion is that history – as talked about by the project planners from the National Museum – can be seen as sharing features with botany as developed by Linné. Just as the botanical system was seen as external to the data it consists of, the understanding of history, as expressed by the project planners, was likewise seen as if from an external position with regard to the data filled into it. History was seen as progressing along a line (the system), and events such as the transatlantic slave trade (data) had to be duly filled in along that line. Filling the history of the Danish plantation in Africa into the place occupied by the transatlantic slave trade did not work – the Danish plantation belonged to ‘another chapter’, as the Danish coordinator framed it, a later chapter. The story of the Danish plantation had its own place on the timeline. In order to produce the generalisation of a universal history represented as a timeline, however, one needs singular instances such as the Danish plantations in Africa and the transatlantic slave trade, to mention but two of the events important for the project planners and for telling ‘our common past’. These are needed to fill the particulars into the same story – a story that by its sameness can ensure bildung, reconciliation and indeed unity, as we saw above. And in order to fill the data into the timeline, one needs to focus on a small conjunction between the transatlantic slave trade and a Danish plantation in Africa. These are needed – as different points – to fill the particulars into the same story. The small conjunction in this case could be the shared implication of ‘whites’ making use of African labourers. The conjoined points are both structured according to a course of events; they both have a beginning and an end, which gives them the possibility of covering a period in time, or being a ‘chapter’ as chapters follow each other and chart progress through a book. Where the comparative feature in the Linnéan system was the reproductive organs of plants, in the case of history in the Frederiksgave project it could be that events related to the European colonisation of Africa are thought of as having a temporal beginning and an end. This makes the events available to progressive sequencing such as can be found in a timeline, where the year 1750 logically comes before 1830. With greater or lesser precision, the events are given a year or a period in time when they occurred. One event succeeds the other, and the fact that the events share the same structure and the possibility of being progressively sequenced unites them in this small conjunction that orders the particular events as different while affirming the system as overarching and general. In order to generalise a universal history (or fruit/Nature) as a system waiting to be filled in with data in the form of particular periods (or apples and pears/species), one needs to structure the singular events according to an external timeline by foregrounding their ability to have a beginning and an end (i.e. their possibility of being designated to an annual period) and backgrounding other potential similarities and differences. The point is that this operation requires effort and collaboration – and if the collaboration is threatened by a mixing up of particulars it is important (for the sake of the system) to dig in one’s heel to get history back on track. Heritage scholars Logan and Reeves (2009) have observed that sometimes the local community in which heritage work takes place may refuse to accept national or world interest in their past. The community, they state, might thus have their own ‘different yet equally valid interpretations’26 of heritage sites, particularly if these are sites commemorating or implying ‘acute anguish’.27 The authors go on to state that

Foreign [heritage] professionals can avoid or at least minimise problems such as these by adopting a sensitive cross-cultural negotiation approach in all stages of the commemoration process, remembering that they are working on someone else’s land.28

What is interesting here is that to the Frederiksgave project makers this sensitivity to the cross-cultural setting of the project implied in the design of the project as a symmetric cultural encounter is thought to be achieved by an appeal not to local community involvement but to a universal global history as a shared resource for all. In that sense, one might say, the project was not really perceived as being ‘on someone else’s land’. Instead, the project was designed as if from nowhere in particular – even if informed by bilateral collaboration. The point here, however, is that this is of course in itself a specific perspective, creating progressive world history as the axiom of unity. In other words, history does not pre-exist the singularities, but is made up of multiple instances that may comprise various conjunctions other than a progressive timeline.

Now, to invoke Tsing again, the Common Heritage Project can be explored by asking what happens to the universality of history in a world of friction in which the pre-givens are abandoned and seen – more realistically – as particular contrived figurations of sameness and difference? In a world where universalising ideas are constantly made rather than found? Indeed, the need to ask this question surfaced all the time in my fieldwork material, as we saw above in the case where the universality of history was questioned – and reaffirmed – in the discussions of the guides’ ‘wrong’ stories. The view of collaboration as a way of treating differences and similarities in order to make working generalisations becomes visible in my presentation of encounters as understood in the Frederiksgave project as a relativistic perspective, where one culture meets the other. As we can now see, cultural encounters in a relativistic perspective such as that advocated by the coordinators are, by presupposing that there is a universal form that can be filled out with different particulars, consistent with ideas of a universalism. Both universalisms, seeing history as a given progression of different events and seeing cultures as having the same form but different content, share, as mentioned above, the need for a meta-perspective from where one can see cultures or events from the outside. In terms of the overall discussion of what heritage making involves, the perception of this universal aspiration as a common and neutral system that accords with an external timeline as its ordering principle is crucial, since it allots only one slot for any of the particulars, thereby effectively controlling difference. Except, of course, that difference keeps coming back in to show the contrived nature of such a generalisation. When configured within this particular project imaginary, I suggest that sharing a common past is conditional upon a form of universalising – a common fight against nature and wrong-tellers and for history. What we share is a universal truth (History consisting of encounters between distinct cultures and/or sequences of events) and where we meet it is in this shared ‘landscape’ that is threatened by being engulfed by nature and laissez faire. Difference, such as other stories about the Frederiksgave site than the history communicated via posters, is then understood according to the same universal system, and if it does not live up to the criterion of the system it must be forced into sameness; i.e. corrected to confirm the established story. There is thus a self-fulfilling quality to this way of generalising; it is always ‘right’.

It was in these universalising senses described above that the initiatives from the National Museum could be understood; they were ‘a helping hand’ preserving something presumed to be of universal interest and common value, and ‘the least we can do’ to assist the impoverished Ghanaian nation, as it was often framed by the people involved from the National Museum. In order to fulfil these minimum standards and thereby help the Ghanaian nation to get its fair share of the universal bildung, even though it ‘lacked money to finance these kind of things,’29 as explained by the director in a national Danish newspaper, the people from the National Museum wished to survey ‘all the Danish traces that were severely threatened by decay’, as they repeatedly told me. As a passing remark, the recognition of a natural encounter that acts on and changes the object should once more be noted. In this sense, the museum was not only following its expectations and obligations as the Danish National Museum and the ensuing national legal requirements;30 it was also following the international charters for the conservation and restoration of monuments and sites – particularly the preamble to the Venice Charter (1964), which was often referred to primarily by the Danish architects involved in the reconstruction project at Frederiksgave. The preamble states the following:

Imbued with a message from the past, the historic monuments of generations of people remain to the present day as living witnesses of their age-old traditions. People are becoming more and more conscious of the unity of human values and regard ancient monuments as a common heritage. The common responsibility to safeguard them for future generations is recognised. It is our duty to hand them on in the full richness of their authenticity.31

In the Athens Charter, a predecessor to the Venice Charter, the task of maintaining cultural heritage is normatively seen as a task for the ‘wardens of civilization’ – or, as stated,

[t]he conference, convinced that the question of the conservation of the artistic and archaeological property of mankind is one that interests the community of the States, which are wardens of civilization.32

The salvage operation of surveying the decaying buildings, and the statement mentioned above that surveying all the Danish-built forts and buildings in Ghana is ‘the least we can do’, could be seen as a continuation of a rhetoric germinating in the 1940s on the West African Coast.33 At that time, Thurstan Shaw, one of the first curators of collections in the Gold Coast, stated that ‘no nation can feel truly self-confident or self-conscious if it is uncertain about its past’.34 In the same spirit, Julian Huxley, a scientist, was sent by Great Britain to the Gold Coast among other things to research the development of museums, archaeology and ethnology in West Africa. In a report, he wrote that

knowledge of and interest in the history and cultural achievements of the region will be of great importance in fostering national and regional pride and self-respect, and in providing a common ground on which educated Africans and Europeans can meet and cooperate.35

Here Huxley, like his Danish successor sixty years later, expresses the universal and absolute value of knowing one’s past. Interestingly, he also understands this particular way of knowing as providing a common ground for cooperation between ‘educated Africans and Europeans’. Returning to the ideas expressed by the Director of the National Museum, knowing one’s history was understood as a vital part of being an educated human being. Interestingly, upon closer inspection, as we have already seen, this promotion of a universal history requires a concerted effort. It is necessary to dig in one’s heels and insist on a proper education that can ensure recognition of the universal history and thereby a common ground where we, the Danes, can meet them, the Ghanaians. ‘Education’, or ‘capacity building’ as it was also called by the coordinator, was needed; education and capacity building could provide a similarity that made the idea of a universal history possible and evident, and they both demanded an effort in the form of educational programmes and other forms of promotion since, as Tsing pointed out when identifying the circular argument implied in a generalising logic, this was not something emanating from the universal history itself. Capacity building, then, can be seen as an outcome of the challenge to the universality of history. It has grown as a particular response to an awkward encounter that suggested – for the sake of all – resolving the problem of different ways of understanding how and when the Europeans used the African workforce by erasing the differences and settling the similarities.

Verran discusses what seem to her to be the dangers of such universalising ideas, taking her point of departure in how ‘Yoruba numbers’ have been repressed by ‘universal numbers’. According to Verran, the problem is that the universalist explanation has

legislated the primitiveness of Africans and established the need for their uplifting through development – modern education. Difference is ruled out in universalism as it legislates a particular and, I would have argued, an abhorrent moral order: “You should give up your nonmodern Yoruba ways to become full knowing subjects in the process of making modernity in Yorubaland!” For a universalist, Western colonizing is an agent of progress in Africa. And any notion of postcolonialism is neo-colonialism – a continuing struggle to roll back the darkness through learning to use the given universal categories singularly embedded in material reality.36

As Verran points out, difference, and I would add, truly generative encounters, are ruled out in universalism – there is only one way forward and that is via modern education conveying the only true story and system, to which different events contribute. Together we stand against decay and darkness; so close do we stand, actually, that ‘we’ turn into ‘one’. In the international charters, the Danish Museum Act, and both Huxley’s and Shaw’s ideas, the rhetoric of the sentence uttered by the Danes at the beginning of the new millennia (‘the least we can do’), can thus be seen as a polite continuation or re-enactment of this civilising drive to conserve the artistic and ancient property of humankind – especially when we know that the Ghanaian government lacks the money to take care of these treasures. It was exactly from this normative perspective that the Danish National Museum saw its engagement in Ghana as ‘a helping hand’ or a contribution to preserving valuable heritage. As noted in an article by some of the people involved in the project, the National Museum’s activities in Ghana could ‘contribute to giving the heterogeneous population in Ghana a greater understanding of the history of this still young country’.37 The project, established as a collaboration between trained archaeologists from the University of Ghana and heritage workers from the Danish National Museum, could therefore, as suggested by Huxley in the 1940s, be seen as the academic common ground on which collaboration could commence. Consequently, ‘education’ or ‘training’ were therefore also seen as important elements of the project, and included in the budgets accordingly. This was, however, education that flowed in only one direction, namely from from the educated personnel to the local villagers in order to distribute the shared responsibility for our common past. But education and training were found to be more complicated than initially imagined, and therefore gradually faded from view in the development of the Frederiksgave site – perhaps because the universal value of the common heritage was not so straightforwardly universal after all.

An additional grant was, nonetheless, provided for the training of guides, once the National Museum had withdrawn from the project following its inauguration in October 2007. The issue of training, education and capacity building will be further explored in Chapter Five, but for now I will simply point out that it was an aspiration to establish a common ground for the educated, where they could put themselves at the service of history. Training and capacity building thus become yet another way of ruling out difference and potential tension, since education and history are understood as apolitical and acultural. This apparently creates a new platform for an encounter between lay and expert: the project planners saw their task as one of collecting information from near and far and instilling this information into the uneducated guides and visitors to come, thereby making true history: ‘The goal was,’ as stated on the Ghana Initiative’s homepage: ‘to shed new light on the common Ghanaian-Danish cultural heritage and inform people in both countries about this historical chapter’.38 In light of the above, one might ask what, from the perspective of an ‘academic communitas’, are these cultural encounters in which prevail an understanding of cultural heritage as being of common interest to humankind and an assertion of history as essential to the formation of nations and its individuals.

Cultural encounters, understood as dialogues between two completely different cultures in the geographical sense – in this case, one from ‘the far north’, the other ‘locals’ from the West African coast – are displaced into another encounter in which equal academic partners can, through their joint efforts, enlighten the uninformed Ghanaian and Danish populations about ‘the history of Frederiksgave’, as it was often referred to. The encounter then becomes displaced into one between academics or experts and laymen. This layman/expert encounter, however, was not what the coordinators meant by cultural encounter, and was therefore not talked about in cultural terms. Furthermore, one could say the whole point of the encounter between expert and layman was to turn the latter into the former; the encounter had to be eradicated or made superfluous by enlightening people about the common past, and differences here would hardly fit into the project’s ideals.

Through this synthetic reading, I suggest that there seems to be a tension between, on the one hand, working for the expansion of a universal perspective of history and, on the other, taking an interest in culturally specific perspectives. Built into the design of the Frederiksgave project were two types of encounter: the first could be framed as an equal cultural encounter that can supposedly be reached from an abstracted perspective – namely that of the cultural expert who can compare two cultures. The second is a ‘now’ encountering a past that has to be understood in the right way, and this has to be ensured by capacity building and training which, likewise, can be reached from an abstracted perspective – namely that of a universal history identified with the educated man. Both of these encounters, I suggest, work to preserve rather than generate – more than anything the entities appear as whole given and unquestionable units. By focusing on conservation, the safeguarding of heritage is, as quoted above, ‘the least we can do’ – preservation of already existing data is key. However, in this ideally encounter-free zone of cultural encounter and universal history, a great many new things and uncontrollable events did happen and emerge. Let us look again, then, at the paradoxical combination of relativising and universalising manoeuvres in the making of the cultural heritage projects initiated by the Danish National Museum.

On Common Ground

On several occasions, I found myself sitting bent over a table with a group of people at the National Museum. We were all immersed in old maps of the West African coastline which, in addition to their meticulously handcrafted lines, bore old informative inscriptions. These inscriptions indicated that regions were ‘uninhabited’, that ‘In September, the River Volta bursts its banks and floods all nearby areas’ and, among the still recognisable names of African villages, Danish buildings were marked out, their names underscored with a red pen on one of the maps. All the maps were highly detailed along the coastline, with all the forts marked with names, at times almost unreadable. The level of detail decreased exponentially the further inland we looked. Staring at these maps, we were reminded of the massive European presence along the West African coast and, at the same time, of the limited European access to the hinterland, mainly due to the diseases that took their toll on foreigners.

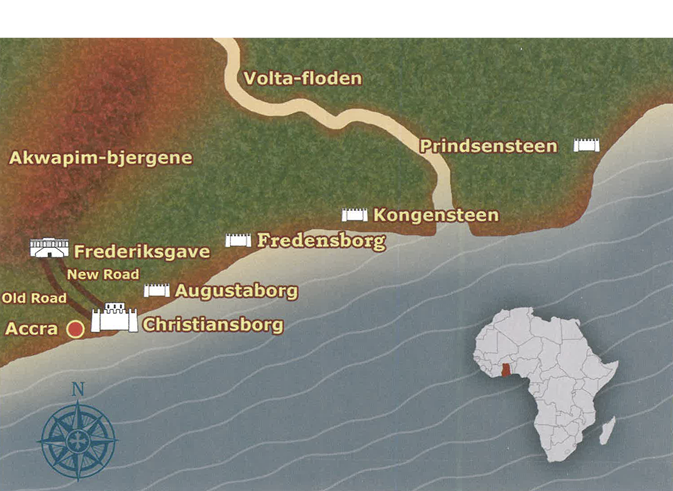

When making posters for the exhibition at the Frederiksgave site, it seemed natural to the project planners to use maps as an illustration, since the compass rose is obligatory on all maps. ‘Then we know where we are,’ we told each other. With this solid ground under our feet we could unfold the history of Frederiksgave. A closer look at the maps indicates where the cultural encounters that motivated the common heritage work are thought to have taken place. A map made by one of the Danes from the National Museum unmistakably shows the Museum’s interests.

Fig. 2.2 Map drawn for an article about the Frederiksgave project published by, and courtesy of, the National Museum of Denmark.39

The map roughly outlines the eastern coast of Ghana, sketched in a few colours and dominated by Danish toponyms. In fact, it is not a map of Ghana but a ‘map of the Danish possessions on the Gold Coast’ as we are told in the text accompanying the illustration. By using the name Gold Coast, the authors point to a pre-independence time when the coastal region had several names among the Europeans, including the Gold Coast, the most durable name, also used by the British colonisers. Along the coastline, the positions of five former Danish forts are indicated by a cartoon-like icon of a white fort. The newly reconstructed Frederiksgave plantation is indicated by a similar icon. On several occasions during the project I had the opportunity to study maps in Ghanaian schoolbooks, and I was struck by the contrast with the map made by the Dane. Remarkably, the latter turned the present-day maps for juniors40 inside out by omitting almost all Ghanaian landmarks and instead making the Danish presence stand out. The map therefore illustrates a Danish presence that is emphasised by the absence of Ghanaian names and cities, except for the ‘given’ physical features such as the river, the mountains and the capital. Considering the minor size of the physical remnants of the Danes’ activities, and the limited awareness that these forts and plantations occasion in Ghana (and in Denmark, as discussed in Chapter One), the size and brightness of the white icons almost make a caricature of the Danish presence. If compared to the map showing tourist sites from the Ghanaian school book, the Danish National Museum’s interests along the Ghanaian coast appear marginal; they are not even noted on the school map, apart from Christiansborg Castle, where the Ghanaian presidential office is located.41 Put differently, the absence of Ghanaian names on the map made by one of the Danes, and the relative lay ignorance of the Danish traces, stand in stark contrast to the large fort icons. The sketched map is accompanied by a small geographically accurate drawing of the African continent. In contrast to the roughly outlined map, the thin lines and curves make the small map of Africa look geographically precise, and the thinly outlined nation-states indicate that it is a map of present-day Africa with Ghana highlighted in red. The continental map is conveniently situated in the right corner, floating in the vast blue Atlantic Ocean. The dual map, as I will call the illustration, can immediately be seen as showing where the cultural encounter took and takes place. Here, one could argue, Danish culture, in the shape of small white fort icons with Danish names indicating Danish constructed buildings, meets local culture, by being on the Gold Coast/Ghanaian soil. However, there is more to the dual map than this straightforward representation of the location of the cultural encounter. As I will argue, the map not only describes a site where the encounter was able to take place, but creates both the site and the encounter in particular ways. It was produced, like all maps, as a cartographical depiction that conjures up certain features and leaves others out.42 So apart from illustrating the museum’s interest in the former Danish constructions, the dual map is also an image of what the cultural encounter might look like from the perspective of the authors of the article in which the map is used as an illustration. By only sharing with maps printed in school books the features of the characteristic coastline divided by the River Volta, the Akuapem Mountains and the capital of present-day geographical Ghana, the dual map conjures up the nation of Denmark on African soil – in Ghana, an African nation among other African nations, as meticulously demarcated by the red colour on the supplementary free floating geographical map of the continent. Apart from conflating the two geographically far-flung nations or territories into one frame, the illustration also entails other conflations. The idea of referring a particular site to a larger and recognisable region, country or continent is a well-known pedagogical trick used with maps; at best it helps the reader localise the particular site. In this case, the idea is to locate former Danish possessions in present-day Ghana. But whereas thin lines and curves make the Africa map look geographically and nationally accurate in relation to present-day borders, the roughly outlined map of the coastline seems more like a sketch. By using two different types of maps (i.e. a sketch and a geographically accurate outline) the illustration conflates different cartographic genres. Furthermore, the pedagogical trick seems problematic, since there is also a collapse in time on the dual map. The sketched map is, on the one hand, an illustration of the coast at a particular period in time – a time when this region was called the Gold Coast and when Danes built forts. On the other, the geographically accurate map of the present nation state is a contemporary map, featuring national borders that were drawn much later.

So what do these conflations in space, genres and time conjure up? How can we understand a sketched, historical, ‘Denmark in Africa’ map appearing in close relation to a detailed map of present-day Africa? In what way is the dual map illustrative of an encounter? I would suggest that this particular cartographical depiction is a compact illustration of a specific idea of encounter that runs through the Frederiksgave project design. The several shifts in genre that are enacted in the illustration appear as unproblematised, seemingly neutral translations. This dual map establishes an axiom of unity, as described above, which unites various particulars by focusing on small similarities and ignoring differences. The generalisation is Denmark in Africa (through a so-called common heritage), and the particulars are two different genres of maps, and two different periods, somehow coming together on part of a coastline. As such, the map is literally grounding the cultural encounters that the two coordinators wrote about then and now – what we see is Denmark in Africa in the past and in the present. In a double movement, the map illustrates the physical sites of the constructions once erected by the Danes on the Gold Coast and, at the same time, it shows the present-day interests of the Danish National Museum in Ghana. Via the dual map, the Danish buildings on the Gold Coast/Ghanaian soil are marked out as the historical and present sites of the cultural encounter. The Danish presence is illustrated both as an historical fact (Denmark built forts on the Gold Coast) and as a present-day reality now being located in Ghana as a geographical site. The interesting thing is that these two sites, illustrated by the duality of the places and times of the encounter between Danes and Africans, are depicted as nesting within each other. By focusing on a small similarity – Danish buildings in Africa – the dual map can be said to naturalise the National Museum’s projects in Ghana via the geographically accurate map. The dual map becomes illustrative of a natural encounter with history, a common ground and illustration of the times when we shared the territories. If readers look at the geographically accurate map and then zoom in, they will find Denmark in Ghana in the form of Danish forts and plantations. And similarly, if readers look at the sketched map and zoom out, they will see an image of present-day Africa. But such movements demand an effort that is often neglected in its circular argumentation: the map shows where we are in order to show where we were, and vice versa – and it does not therefore matter from a Danish perspective whether it is the Gold Coast or Ghana, as long as the generalisation ‘Denmark in Africa’ is affirmed. Denmark may meet its history, but only as a strange timeless presence. And Ghana may be in Africa, but only as a host to Danish buildings and as a naturalised space with a river, a mountain and a capital. By collapsing time and space, the map seems out of proportion. The map thus naturalises the Danish presence in present-day Ghana, as if the only difference between the two elements of the dual map rested in zooming in and out. The map shows the ‘same’ from up close (the rough sketch) and from afar (the outline of Ghana and Africa), respectively. We are thus led to ignore the efforts invested in making such a presence seem natural – that it takes a certain effort to see the Danish forts and plantations in present-day Ghana. One could easily imagine many other things foregrounded – such as, for instance, the sites featured on the Ghanaian school children’s map.43 The result of the unproblematised dual map is that generative aspects of the encounter are ignored; when foregrounded on the geographically accurate map, it is obscured that common heritage, Denmark as former actor on the West African coast, Ghana as a site of plantation exploitation, and so on, all emerge from the making of the Frederiksgave project and from the way it is illustrated by the map. What appears is an obvious coming together of data, just as Linné’s species had their natural position in the system of nature and were not seen as a result of classificatory efforts to make small similarities meet and neglect inherent differences. In effect, then, there is no encounter; all we have is a naturalised image of Denmark in Africa that we can either see close up or from afar, as if nothing had been foregrounded or backgrounded; the dual map shows only grounded common heritage then and now.

Examining What is Left: ‘Danish Traces’

In describing the interests of the Danish National Museum, a particular expression, namely that of ‘Danish traces’, gained a foothold among those involved in the Ghana Initiative. It was repeated over the years of the museum’s involvement in Ghana. For example, even in 2006, in an article written by the Danish coordinator and the Danish archaeologist excavating the Frederiksgave site, the expression was used as a sub-headline stating ‘Lots of Danish traces’. The sub-headline was followed by a description of several plantations and Danish forts.44 It also appeared in a slightly different version as an image of ‘walking in the Danes’ footprints’ – in Danish, footprints would be translated as ‘foot-traces’ – referring to present-day visits as a close re-walking of the former Danish forts and plantation sites.45 The expression was solidified in a new initiative following the Frederiksgave project but still under the overarching Ghana Initiative, entitled ‘Conservation of Danish Traces’ – abbreviated in everyday speech to ‘Danish Traces’. In line with the cartographic encounter, ‘Danish Traces’ framed and condensed, I will argue, the National Museum’s interests in Ghana, and can be explored to further qualify the ideas of common heritage embedded in the museum’s projects. After the completion of the Frederiksgave project, a group of people who had been involved announced that

the museum looks forward to continuing, together with the Ghanaian partners, to communicate our common history, including to ensure that the physical traces, our common material cultural heritage, are preserved for the future.46

The ambition of the preliminary study into ‘Danish Traces’ was to obtain an overview of the Danish remnants in Ghana in order to support further applications for funds in Denmark. This was attempted through an architectural registration and description of all Danish physical structures in Ghana, concurrent with an historical search in various archives in Europe and Ghana for Danish traces regarding our common Danish-Ghanaian past. These works were accompanied by anthropological fieldwork at the various sites in Ghana in order to explore and collect knowledge from, and ensure the interests of, the people living in or close to the sites. I conducted this third part of the Danish Traces project, seeing it as an opportunity to further study collaboration and interest in common heritage. All three studies were conducted in order to advise people at the National Museum on the possibilities and relevance of renovating other sites, which might thus qualify for further funding. The project echoed an encyclopaedic ambition to trace, survey and collect information on all the physical Danish traces related to Ghana in the period up until the Danes officially left the coast in 1850. And it echoed an idea of specialists being sent out into the world to gather information upon which new actions could then be taken in offices back in Copenhagen. On a small scale, we were re-enacting the totalising knowledge-building ambitions of former European explorative scientists. Whereas the expansionist conquerors’ ambition was, as Pratt brilliantly reminds us, to take over huge tracts of land, appropriate and control resources and civilise people, the European travelling scientists claimed no such transformative infringements. By tracking, observing and registering Danish traces through our knowledge-building project’s ‘descriptive apparatuses of natural history,’47 we were creating ‘a new kind of Euro-centic planetary consciousness’.48 Pratt refers to this utopian descriptive scientific paradigm, both abstract and benign, as ‘anti-conquest’.49 Essential to the notion of anti-conquest is the idea that description, often made with the observant eye, does not interfere with the world. Through a variety of techniques and tools, a removed observer carefully comes into being and systematises the world by way of description rather than conquest. I suggest that the National Museum’s survey project, referred to as ‘the least we can do’, can be seen as such an anti-conquest – a benign non-interfering process of description. One might argue that, together with the museum’s initiatives in the cold colonies, the mapping of the hot colonies created not a Euro-centric planetary consciousness, let alone a cosmopolitics,50 but rather a nationally-centred one – a consciousness of all Danish traces spread over the planet. So, rather than teaching the Danish population about ‘the cultures of the world, and their interdependence’ as the Museum Act (§5) has it, the museum inverted the argument via its focus on the former Danish colonies. By this emphasis, the initiatives actually taught about Denmark in the world. The relation between a national focus and a universal history is seen as just a matter of having a particular starting point – a Danish contribution to history, a case or an event from which to begin filling in data on the given universal storyline. In this way ‘nations’ become an unquestionable, one might even say innocent, ordering of particular events.

With the Danish Traces project, the National Museum was not engaged in reconstruction work, as was the case with the Frederiksgave project, nor was it interested in taking over land, resources or people. The express idea with ‘Danish Traces’ was only to make pre-studies that could qualify applications for future initiatives, including reconstruction projects. The intention with ‘Danish Traces’ was to build knowledge in order to gain a complete idea of what the Danes had left behind. It was primarily a meticulously explorative and descriptive manoeuvre. With this all-encompassing ambition, the project went far beyond the small white icons on the map entitled ‘Danish possessions’, as indicated above. Several severely dilapidated former Danish plantations were traced, many only with a few stones remaining that could indicate a ground-plan. Merchant houses built by Danes in the neighbourhood close to the main Danish fort of Christiansborg in Accra were ‘discovered’, ‘investigated’, ‘registered’ and added to maps and lists. Archives in Ghana, Denmark, Germany and the UK were visited, and additional information and photos unearthed and, likewise, added to the expanding knowledge bank. These physical Danish traces on Ghanaian soil, partly illustrated on the map discussed above, were the raison d’être for the Danish National Museum’s presence in Ghana. Or, to put it more precisely, the museum was present in Ghana in order to take care of (i.e. to collect, register, preserve, research and communicate – see the Museum Act §2) these Danish traces, since the Ghanaian nation lacked the money to do so. As ‘wardens of civilization’ (Athens Charter), or rather as ‘wardens of the Danish nation’, the museum followed the old international charters, taking on the task of caring for a ‘common cultural heritage’ for the future. By engaging in such a knowledge-building project, just like the former explorative scientists, the museum created a national consciousness (to be extended to the Ghanaians by way of capacity building, as we saw above), in this case particularly with regard to the outreach and influence of Danish history and heritage.

If the ‘Danish Traces’ project focused on surveying and describing what the Danes left behind, in what way did it fall within the overall ideology of cultural encounter? I will look closely at the specific making of these sites, and explore how they were turned into stories of ‘our common past’. Following on from this, I shall explore some encounters at these particular sites – in these contact zones – and see how the encounters and the entities that take part in them are constituted.

A Non-Encounter in the Meeting Room

In an article written by most of the Danes involved in the Frederiksgave project, the sites of the cultural encounter and the consequences of the Danish influence were described in the following way:

In addition to Danish toponyms and a long list of descendants with Danish family names, the Danes left six Danish forts, a long list of plantations and merchants’ houses behind.51

Following on from this interest in the Danish influence and what the Danes left behind (which became the physical manifestations of the cultural encounter), I have met a good many people who have old Danish/German names such as Wulffs, Svanekiers, Lutterodts, Engmanns and Richters to name but a few, precisely because they are the descendants of former expatriate officials sent out by the Danish State. These descendants live in and/or own parts of family houses built by these expatriated ancestors who centuries ago established a family on the coast. Present-day Ghanaians with Danish/German names could literally be seen as the children of cultural encounters, understood in terms of nations. As such, they attracted a great deal of attention from the National Museum. The museum’s attention was all the greater because these families owned the old houses that their expatriated forefathers had erected using Danish measurements, architecture and materials, meaning that the houses qualified as Danish traces. In this way, what was known among the Danes from the National Museum as ‘Wulff’s House’ or ‘Frederichs Minde’,52 as the founder W. J. Wulff called his house, was an obligatory stop on official visits from Denmark. In the area where the house is located, however, it was not recognised as Wulff’s House but went under another family name. Employed by the National Museum to detect these family houses, I came to see how complex and contested they were as manifestations of cultural encounters.53 Patrilineal inheritance down many generations had led to a proliferation of legal ownership of the houses to such an extent, I was told, that some of the Danish-built houses I visited now had over 200 formal owners, often spread all over the world.

Wulff’s House was a special case for the National Museum since, according to the Danish architect, it was ‘very authentic and well preserved’. Furthermore, it was situated on the road leading up to the former Danish fort of Christiansborg. Another recommendation of the house was that W. J. Wulff, its founder, had written a diary that was published in Denmark in 1917, and he was therefore well-known and read among interested Danes. The house, to the National Museum, provided a unique opportunity to meet with this semi-famous forefather. Over the years when the National Museum was engaged in the Frederiksgave project, interest in the house increased among people from the museum, culminating in an official visit in the autumn of 2008 by the museum’s Head of Ethnographic Collections, the coordinator for the projects under the Ghana Initiative, and myself. Two years previously, I had joined the Director of the National Museum who, together with the Danish and Ghanaian coordinators and the people from the Danish fund granting money to the Frederiksgave project, had also visited the house. In 2008 we therefore knew that the people living in the house were happy to show their house to interested Danes. Their hospitality was always repaid with some money, discreetly passed to the person in charge of the visit. As arranged with the residents, we drove down ‘Castle Drive’ leading to Christiansborg Castle, where the Presidential office is located, shortly before 10 a.m. one morning in 2008. In addition to Wulff’s House, a number of other big old houses are majestically positioned along the eastern side of this road. They, or their backyards, form the border with the slum area of Osu. On the other side of ‘Castle Drive’, to the west, a vast green area leading up to ‘Independence Square’ forms a contrast to the densely populated slum area. Today it is a huge green lawn with an allotted area for small-scale farming – and patrolled by the military that guard the presidential offices in the castle. It was once a part of Osu village, but due to several bombings and fires, the last at the end of the nineteenth century when the British were forcing the inhabitants to pay taxes, the area had been left a wasteland. This sudden laying bare of a vast area generated many fantasies in the minds of archaeologists – maybe this huge area could be excavated, just as archaeologists had excavated a similar ground in Elmina.54 In addition, a small old Danish cemetery built in connection with Christiansborg Castle takes up a part of the vast area. Together with other curious Danes, I have made several attempts to visit the cemetery. Because of its proximity to the presidential castle, however, it is not easy to gain access without special permission, and on several occasions we were chased away by the military pointing their guns at us.

On this late morning in November, the sun was already strong; the military were patrolling in the shade under the trees along the road. Our driver knew that, being so close to the presidential palace, he should not search too long for a place to park the car. Immediately after passing Wulff’s House he therefore turned the four-wheel drive into a small, dusty, dilapidated space. On rubble, open drains and huge furrows in the red soil, he smoothly parked the car. Our small delegation from the Danish National Museum was received by three men. They welcomed us, guiding us into the main room on the first floor, apparently characteristic of Danish-built houses in the region. A fresh breeze constantly aired the room, and we soon cooled down. On several occasions the Danish architect had talked about his fascination with the skilled builders of the past, and the intelligent design built into the houses. With the right materials and construction skills, he explained, they had succeeded in making a house which, in contrast to houses built in Denmark, could resist the strong sun and, at the same time, be as cool as possible. And it certainly felt good to be in this centrally located large ventilated room, with its open windows and fluttering curtains. Indeed, the builders had taken the encounter with nature into consideration. Along the light blue walls covered with old pictures, sofas and big chairs were lined. Our host asked us to sit down, and our eyes immediately began to explore the room. The beamed ceiling, the boarded floor and the old framed photographs of descendants of W. J. Wulff all reminded us of why we were there. A formal presentation of all the people in the room followed, after which we were given a cold soda. A photo was passed around. It was from the 1980s, and revealed that a Danish minister had made it to the house – the photo provoked a smile from the Danes. To me, it was not just any minister but one that immediately took me back to demonstrations in the huge square in front of Christiansborg, the palace housing the Danish parliament in Copenhagen. Together with what seemed like all the Danish students and pupils in the country, I had demonstrated against his reforms and belted out satirical songs. But here in Wulff’s House in Accra, close to another Christiansborg, we and the minister suddenly shared the same interest, as became apparent from the photo. Through the minor conjunction of being a Dane visiting descendants and their Danish constructed house in Africa, we created and participated in the same axiom of unity that could be formulated as a Danish interest in Danish physical traces in Ghana/Africa.