Thinking in forests

Lys Alcayna-Stevens

Introduction

The seeds of this chapter grew from a kaleidoscope of contrasts made between ‘field’ and ‘home’ by fledgling field primatologists studying an endangered and elusive great ape (the bonobo) in the equatorial forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo. During both fieldwork and retrospective interviews, young scientists reminisced of ‘a separate world’ which was ‘remote’, ‘isolated’, ‘pristine’, ‘undisturbed’, ‘interconnected’, ‘alive’ and ‘easier to breathe in’.

Initially, I was tempted to read these narratives alongside familiar global discourses of habitat loss and environmental crisis, an exoticising or fetishising of African wilderness, and a nostalgia for simplicity, authenticity and immediacy. And yet, as I thought more about their reflections, and my own experiences in those same forests, and as I pored over my notes and re-listened to interviews, I began to pay more attention to those moments in which researchers themselves punctuated their reflections with caveats; ‘this sounds like a cliché’ they would admit, insisting that they were unable to find the words to fully capture their experiences of the world around them (and beyond them), their own subjectivities and the passing of time in ‘the field’.

What to make of these caveats? The apparent failure of language to capture experience has spurred me to reflect on the kinds of embodied ‘edgework’, or ‘cuspwork’, through which these neophyte field scientists navigate the known, the unknown and the inarticulable, as they come to appreciate the forests in which they live and work when searching for, following and studying elusive and itinerant bonobo communities. In using these terms, I am inspired by the invitation of feminist geographer Kathryn Yusoff (2013: 209), to ‘think along the cusp’ or ‘the edge’ of the insensible when attempting to apprehend issues such as biodiversity loss and climate change.

Feminist scholarship has long challenged the neutrality, rationality and disembodiment on which scientific objectivity rests (Barad 2007; Haraway 1988; Myers 2015; Myers & Dumit 2011). Many of these theorists have taken a phenomenological approach, privileging the body of the scientist in their analyses of scientific work. Seeking to capture not only scientists’ narratives and impressions, but also the world with/in which those impressions are formed, they write within relational and materialist frameworks which allow them to challenge assumptions about the kinds of labour required to do scientific research, and reframe this work as premised on ‘the capacities of a lively sensorium tethered to a lively world’ (Myers 2015: 15).

These scholars have also explored the limits of knowing and understanding, including the ways in which such limits are stretched in the messy, fleshy-semiotic encounters between scientists and animals (Despret 2004, 2013; Haraway 2008). These encounters are perhaps at their messiest in ‘the field’. STS scholars and ethnographers who have followed scientists to the field have examined the ways in which they attempt to stabilise their data and control for the vitality and excess which encroaches (Henke and Gieryn 2008; Walford 2015). Field primatologists themselves forgo the more systematic, reproducible and controlled nature of lab-based cognitive experiments, and I argue that an ethnographic exploration of their edgework in the forest can dovetail the limits of knowing and relating explored by feminist approaches to animal science, and feminist geographies which explore the indeterminacies of the contemporary environmental crisis.

The chapter draws on intensive ethnographic research at one bonobo field station, shorter visits to three other bonobo field stations (all in the Democratic Republic of Congo), and ongoing exchanges with the primatologists who work at these sites. In field primatology, there are many unknowns, and much remains unpredictable: where the primates will go, what they will do, whether it will even be possible to find them. The bonobos are free-ranging, sometimes travelling up to 10km in a day, and there are no tracking devices with which to find them in the dense forest. Researchers have very little equipment (a pen, a notebook, a pair of binoculars and a GPS), and must rely on their bodies to find and follow bonobos, and to collect data. The forest itself is often just as unpredictable as the bonobos; researchers are sometimes attacked by bees or wasps and can find themselves in parts of the forest which are almost unnavigable due to swamps, rivers or tangled vegetation.

‘The field’ is all the more compelling, in studies of science, because domestic and professional life are not as separate there, and the ethnographer has access to both. Junior research scientists often live at field sites for up to 9 or 12 months. While this chapter will not touch on researchers’ more domestic activities, it will examine those interstitial moments in which field scientists cannot collect any data because they have ‘lost’ bonobos – in which bonobos have melted into the shadows of the forest and disappeared, sometimes for hours, sometimes for days or weeks. I am interested in what happens in those moments of waiting, searching and wondering. Indeed, it is often during those interstitial moments that the forest comes to the fore and begins to captivate the researchers’ attention. This shift opens up the possibility for different kinds of thought – thoughts which are embodied, undirected, uncertain, introspective and indeterminate. That is, kinds of thought which are seldom associated with the neutrality, rationality and disembodiment of scientific objectivity.

Phenomenological approaches have allowed for a resolution of the mind-body problem in philosophy and social and psychological science, bridging the distinction made by Enlightenment philosophers between thinking (reason) and feeling (sentience). For phenomenologists, thought is felt. Nonetheless, thinking and feeling remain fairly exotic topics in anthropology, due to the discipline’s focus on social patterns and dynamics. ‘Psychological’ or ‘cognitive’ matters, such as emotion, inner dialogue, mood, free association, reverie and imagination, have often appeared too unstable and too individuated to qualify as an object of social study. Unlike behaviour (in the form of ritual, exchange and performance) these experiential phenomena have little empirical ground.

Social scientists have made many attempts to grapple with emotion and experience, most of them engaging with debates in phenomenology and materialism.1 Other approaches have prioritised semiosis. Rising to prominence with Geertz’ interpretive anthropology and finding its most recent expression in Kohn’s (2013) Peircean ‘anthropology of life’, semiotic approaches have emphasised communication, symbolism and shared meaning. In order to extend anthropology’s reach, Kohn uses Peirce’s triadic semiology to argue that all life forms engage in processes of signification. He argues that iconic signs and indexical signs must be brought into the anthropological agenda (heretofore dominated by symbolism), because icons and indexes are the signs that non-human organisms use to represent the world and communicate.

Kohn then makes a connection with thought, arguing that all beings are thinking beings, and that living environments are environments of thought. However, using the inspiration of the forest, and taking ‘sylvan thinking’ (Kohn 2014) in another direction – one inspired by feminist geographies and studies of science – I want to untether thought from communication and semiosis, and to linger on those moments when meaning fails to cohere and when understanding appears beyond one’s grasp. Taking sylvan thinking in this direction necessitates ‘staying with the trouble’ (Haraway 2016) of alterity and lingering on the ways in which indeterminacy emerges as bodies flourish and as bodies die. I am interested in the echoes, traces and palimpsests of elsewheres and elsewhens which render thought simultaneously relational and beyond the relation. Thoughts appear then as tendrils reaching out to others (times, places, being), but seldom connecting.

Attention to thought in ethnographic writing perturbs both a commitment to the empirical and a commitment to the social. Thoughts are ephemeral and wayward, and others’ thoughts are often opaque or only indirectly available to us. In an attempt to grasp the kinds of thinking which the forest facilitates, I will employ ethnographic fiction, and follow a composite character whose movements – both wandering and wondering – are based on formal interviews and informal conversations with scientists, and on my own experiences of living and working in the forest, alone and with others. There are many limitations to this approach, and this composition should be read as an experiment rather than an analysis. It is an experiment which allows me to linger on the mundane, the habitual, the non-event, and on the interstitial moments in which thought meanders and mutates and brings alterity and understanding in and out of one’s grasp.

Indeterminate

Our field scientist methodically ticks off her mental checklist and packs the remaining objects (a satellite phone, her GPS and binoculars) into her backpack, making sure that her notepad, pencil and compass are securely tied to the belt loops on her waistband. Eager to leave camp, she wolfs down a bowl of rice and boiled cassava leaves prepared by the Congolese cook, and muses on where she might search in order to find the lost bonobos. She signs herself out in the ‘daily book’ and notes down the names of the trails she plans to walk this afternoon.

It is nearly noon as she walks quickly through the camp towards the forest path, and the sun is already beating down on the thatch roofs which provide shade for the researchers’ tents. Sweat begins to bead on her forehead. She steps over the fallen tree which marks the entrance to the forest and is engulfed by the hum of insects and the cool shade of the dense canopy. The stale heat and exposure of the camp melt away and she picks up her pace, feeling purposeful.

She is aware of the forest beneath her feet, stepping over lines of driver ants and avoiding tree roots. Her lungs feel capacious, and her legs feel powerful as she side-steps and skips over uneven ground. Passing another fallen tree, she takes a deep breath, inhaling the smell of sap, bark and crushed foliage. She feels connected to the forest and kindled by the unseen activity around her. If she had been here six hours earlier, the beam of her headlamp would have bounced off the back of the retinæ – the tapetum lucidum – of hidden mammals and insects, alerting her to their presence. Now in the daylight, even if they are there, they remain unseen.

After some time walking and letting her thoughts unwind, her mental checklist replays itself and she begins to doubt that she put the second notebook in her backpack. She stops and takes the bag off her back, resting it against the buttress of a giant tree – she doesn’t know the species. Her notebook is there.

She makes the most of the pause to take a swig of water and wipe her brow. Now that the breeze driven by her movement has stopped, heat emanates from her body and appears to coagulate beneath her shirt. She pulls at her collar to fan herself a little and licks the salt above her lip.

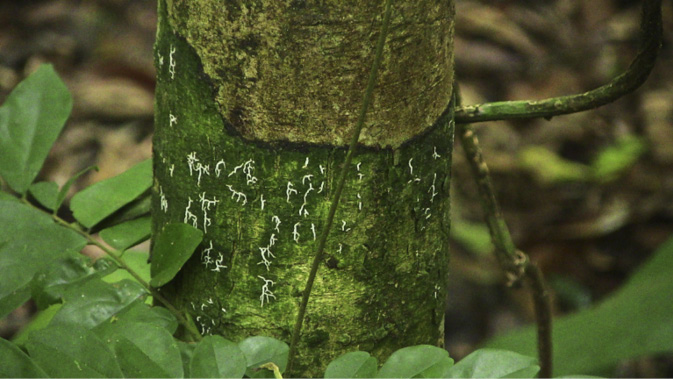

So much is unknown in the forest. A stream of light filtering from above and glinting off a russet leaf catches her attention. Behind it is a slim, moss-covered tree trunk, bright green, and covered in intricate and staccato white markings. She assumes they must be some sort of fungi, even if, in that moment, they look to her like ancient or alien glyphs or simple drawings of antelope or birds. When they have talked about the markings in camp, others have suggested that they look like dancing figures.

Fig. 2.2 Tree trunk covered in intricate and staccato white markings – fungi ‘glyphs’ (Photograph by Lys Alcayna-Stevens, 2012)

She never ceases to be amazed by the forest. One can easily transform markings into hidden signs with one’s imagination, just as one can easily miss or misinterpret other elements which could have been read as signs; the tracks which Congolese hunters follow with great skill, for example. Cycles of life and death render these signs even more ephemeral. She has seen insects camouflaged as sticks and stones, detectable only by their movement – if at all. When they die, they become invisible for ever more.

She is also amazed by the speed with which things grow and re-grow, Lazarus-like, in the forest. Even here, not far from the ‘buttress tree’ (as she calls it), is a fallen log. Its branches are bare and mostly disintegrated, indicating that it must have fallen several weeks or months before. And yet, growing out from the broken bark, vertically towards the sky, is a new branch. A sapling? The tree is still alive.

At times, she feels overwhelmed by the forest. By its magnitude and its majesty. It is an uncanny feeling. If anything, the forest emanates… indifference. As she touches the buttress tree’s rough, mossy bark, she feels insignificant. The powerful feeling which comes from that realisation cannot be described as either good or bad. It feels like a kind of rejection, but one that leaves her winded rather than stinging. And grateful somehow... She grazes her fingertips lightly down and off the bark, takes a deep breath, swings her bag onto her back, and begins to walk again, picking up the pace.

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) exist only in the equatorial forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo and have been very little studied compared with their close evolutionary cousins, the chimpanzees.2 The two ape species are separated by the Congo River, with bonobos encircled by the curve of the river along its left bank, and chimpanzees ranging beyond it, in forest and forest-savannah landscapes to the north, east and west, from Senegal to Tanzania.

Unlike evolutionary psychologists, who conduct lab-based experiments to explore the limits and potential of primate minds, field primatologists are committed to the principle that studying a species in the environment in which it evolved can provide the most insight into the factors which have shaped its body, mind, behaviour and social organisation. This issue is of particular relevance to questions of bonobo evolution, because current hypotheses suggest that some of the most significant differences between bonobo and chimpanzee social structures and behaviour lie in their different ecological niches. As the theory goes, while chimpanzee females often reside alone in a territory which has only enough fruiting trees to support them and their offspring, bonobo females live in forests abundant in ‘fall-back foods’ (terrestrial vegetation), and females are therefore able to travel together. In terms of social structure, this has led to the formation of male coalitions (and male dominance and violence against females) in chimpanzees, as groups of males patrol and control the territories of several females, and a more egalitarian and peaceful social life in bonobos, where females are able to form coalitions which limit male dominance and violence.

For field researchers, the forest is an essential component in their study of bonobo ecology, social structure and behaviour, and much of the data they collect is about seasonality in fruiting trees, bonobo feeding, travel and nest-making behaviour. However, the forest also ‘gets in the way’ of their research. Visibility is hampered by thick vegetation, and researchers’ ability to follow bonobos is slowed by swamps and rivers, which bonobos are able to bypass by sticking to the canopy or making use of fallen logs too precarious for researchers to clamber over. Furthermore, hookworm infestations from walking through swamps, and allergic reactions to the stings inflicted when researchers disturb bee hives or wasp nests, can force researchers to spend days in camp recovering, and thus miss valuable data collection opportunities.

While researchers learn about the forest by following and even mimicking bonobos’ movements within it (Alcayna-Stevens 2016), many of them have acknowledged retrospectively that it was in the hours and days spent searching for lost bonobos that they most appreciated the forest. Freed from the pressures of data collection, they had time to linger, to examine odd or unusual things in more detail, to revel in the forest and to drift into reverie.

It was in retrospective conversations that I had the opportunity to discuss these solitary moments with researchers in more depth. I think of the distinctions they would draw between ‘home’ and ‘field’ (often used interchangeably with ‘forest’) as a kaleidoscope of contrasts because the distinctions do not map neatly onto each other, and at times they even contradict, with the same terms being used to compare and highlight different differences. For example, an urban and ‘artificial’ home in which one is isolated and ‘cooped up in a box with electric power all the time’ was often contrasted with a ‘verdant’ forest in which one is ‘connected’ and ‘very much in tune with what’s happening around you’. At other times, however, constant connection was what characterised life at home, while the forest – using an electronic metaphor – was described as ‘a place to recharge your batteries’.

Similarly, life in the field was often described as ‘simplified’, ‘predictable’ and ‘limited’, in contrast with an ‘overwhelming’ return home in which one would ‘have to deal with hundreds of options’. At other times, it was the forest which was described as ‘unpredictable’ and with ‘so much going on it’s hard to keep track’. The passage of time was also conceptualised through a variety of contrasts. Some researchers described days in the forest as endless and full of events, while the ‘outside world’ was described as speeding by with very little happening. At other times, researchers described the changes and events (missed weddings, celebrations, newsworthy occurrences) which happened in what they also called the ‘real world’, while very little happened in the forest. In all cases, the contrasts served to capture the timbre and tenor of their experiences, if only partially.

One can read within these contrasts a nostalgia for simplicity, authenticity and immediacy, a desire for connection and an exoticising or fetishising of wilderness and nature. It is a familiar nostalgia. Scholarly and popular accounts of globalised late capitalism are often shot through with anxious and nostalgic notes (Stewart 2013): a ‘disembedding’ of social relations from ‘local contexts’ (Giddens 1990), and a disconnection from place, which was described by Said (1979: 18) as a ‘generalized condition of homelessness’. But these are not simply narratives. Sensory regimes, like bodies, are shaped by the processes of capitalism, colonialism and biopower. Social scientists have examined the ways in which such processes leave bodies ruptured, exhausted and abandoned, afflicted by toxicity or obesogenic ‘slow death’ (Das 1996; Povinelli 2011; Chen 2011; Berlant 2007). Researchers’ descriptions capture something less dramatic, but equally beyond narrative and representation. These simultaneously pedestrian and prodigious experiences of ‘lethargy’, isolation and oversaturation are captured powerfully in the words of one researcher:

I felt more alive in the forest. I was very aware of this constant cycling process of life and death and regeneration. It’s hard to explain, but you do have a feeling of connectedness. It’s the level of solitude and nature that I need to feel normal. Here, sometimes I feel like I’m having trouble breathing, I feel more lethargic, I have more headaches. The best way to describe it is I just breathe better in the forest.

It is the caveats – ‘it’s hard to explain’, ‘I know it sounds silly’, ‘I’m having trouble expressing it’, ‘I can’t articulate it’, ‘I know it isn’t exactly true, but it feels like…’ which interest me most here. These are not simply narratives drawing on established tropes of wilderness and disconnection. They are also attempts to express and verbalise vital, excessive and ineffable experiences.

The impression I have, from both informal and formal conversations, and from my own experiences in the forest, is not that language here fails to capture an intuitive understanding of the forest. If anything, what they appear to point to is that the forest is fundamentally other, and beyond one’s grasp – and that this is one of the reasons it is so compelling. Researchers continuously come across plants, animals, fungi and other phenomena for which they have no name and no explanation. They sometimes search for the most striking of these lifeforms in the mouldy paperback field guides stored in a metal crate in the camp depot. But, as none of these guides address little-studied central African flora and fauna in detail, their efforts to identify are not always successful.

At times mysterious, the forest is also mercurial. Walking a few hundred meters, it can transform from a cool, open understorey, to a dense, hot and almost impenetrable overgrowth of terrestrial herbaceous vegetation. It is mercurial because it is multiple. The animals within it often attempt to evade discovery. ‘Crypsis’ is a term used by ecologists to describe an animal’s ability to avoid detection by other animals. It can refer to strategies of concealment, including nocturnality, camouflage and mimicry. Phasmids – also known as stick insects, leaf insects, ghost insects or ‘walking sticks’ – offer one of the most striking forms of crypsis.3 Many use ‘motion camouflage’ by swaying or rocking in the breeze like leaves or small branches, or, alternatively, entering a ‘cataleptic state’ in which they adopt a rigid, motionless posture which can be maintained for a long period, or ‘thanatosis’ in which they drop to the ground and play dead, becoming indistinguishable from the leaf litter of the forest floor.

Uncertainty and indeterminacy are anathema to the goal of science, which is to explain and to understand. And yet it is the imponderabilia, the unanswerable, the unfathomable and the indeterminate which research scientists find so compelling when thinking with and about the forest. After all, even if uncertainty and indeterminacy have no place in science’s goals, wonder and curiosity are the seeds of the scientific endeavour. A brush with the innumerable other worlds which ‘graze’ our own (Yusoff 2013) is what appears to produce a feeling of connection in researchers to something larger than themselves, in all its multiplicity. Theories of affect and semiotic approaches are inadequate frameworks for capturing this indeterminacy because of their emphasis on the social, the shared and the communicative. Reading scientists’ narratives with Yusoff’s theory of ‘cohabitation’ in mind, they are not about what is shared or communicated, but about an acceptance of connection irrespective of asymmetry, non-rapport, nonrecognition and indifference.

Introspective

After walking for nearly an hour, our field scientist decides to stop. She has reached another large ‘buttress tree’, which marks the beginning of one of the most southerly trails. The bonobos were last seen near here two days before. While it seems unlikely to her that they would still be here after two days, she has been surprised before to find them close to where they were lost.

She plucks two large, broad, waxy leaves from a nearby arrowroot plant and places them between the buttresses. She sits on the leaves and drinks from her bottle. Bathed in the dappled light of the canopy, she looks languidly around, her knees up, elbows resting on them, her water bottle dangling from her index finger by its lanyard. After walking for so long, with her mind wandering along other paths, her head feels fresh and empty.

As the heat builds around her body, her thoughts too, seem to catch up with her. She can feel her heart beating, and her muscles hum like the insects in the undergrowth. She makes a mental note to walk more often when she returns home. To spend more time in nature. She takes another sip of water and tries to recall another mental note she had made to herself as she walked, but has momentarily forgotten. It was a question she had wanted to ask her parents next time a batch of emails would be sent out with the satellite radio system – ah yes! That was it: Are there native wild honey bees in Europe, or are they all feral?

She sits for a moment, lost in thought. Then she takes her second notebook from her backpack and notes the question down. As her pencil scratches along the paper, other thoughts come back to her – other people to email, belongings to organise or look for in camp, an article someone mentioned finding in the depot about bonobo language experiments, which would probably take a while to find, buried in a large metal crate, under other yellowed, wrinkled and mouldy papers. She scribbles down some of her other thoughts into lists. Lists of things to do in four months, once she gets back home, books to read, people to visit, recipes to experiment with…

She enjoys making these lists in the forest. The lists are all the more satisfying here because there is nothing she can do to complete them until she returns home. Here, she is in a kind of limbo, where lists can be conjured but not executed. She never has a to-do-list weighing on her mind the way she does back home, because everything she needs to do is almost always both pressing and immediately realisable. She wonders how long she will keep doing fieldwork, whether one day she will tire of this itinerant lifestyle and of the stresses which fieldwork can impose on personal relationships.

She muses on that ‘home self’, whose life and priorities are so different from her priorities here. She is a different person, inhabiting a different body, when she is in the field. When she first arrived in Kinshasa, she was hit by the hot, heavy, evening air of the runway and a smell of… not-home. She isn’t sure how she would describe it. When the little bush plane dropped them off near the villages and she was finally able to enter the forest for the first time, it was this cool air, brimming with the scents of different vegetation that connected her to why she had come and what she was here for, and to all of the discomforts she was willing to endure in order to focus on and collect her data.

The thought of her data takes her mind back to the bonobos. Where might they be? They had been walking less in the days preceding their disappearance. Perhaps they were tired. Or, more likely, they had been sticking around one patch of forest, waiting for the large, mature Dialium trees to come into fruit. She decides to keep walking. She hasn’t quite reached the part of the forest where she thinks they might actually be, and there are no signs that they are in this area anymore. She will walk to a large fruiting Dialium slightly further to the south. That will be the place to pause and wait for them – if they are not feeding there already…

Time spent in camp is usually time spent eating, washing, organising things or inputting data into the camp computer. When bonobos are lost, the forest offers researchers an opportunity for quiet reflection, for solitude, and for introspection and prospection – a moment to think, and to visualise thoughts, in the form of letters, diaries, notes, doodles or lists. In these moments, researchers ‘lose themselves’ in a very everyday and un-spectacular way.

Building on Barad’s (2007) agential realism, according to which phenomena and objects do not precede their interaction, but emerge through encounters or ‘intra-actions’, Yusoff (2013: 210) asks ‘how to understand the durability of intra-actions, beyond the intra-action itself?’ She poses the question in order to think through enduring environmental harm, toxicity and degradation. Here, the question inspires me to linger instead on the ways in which subjects are connected to the world through the echoes, traces and palimpsests of elsewheres and elsewhens which emerge in thought.

While relatively marginalised as an object of anthropological examination until the 1980s, dreaming, and its relationship to ritual trance, spirit possession and oneiromancy, has received increased attention in the last few decades.4 Galinier et al. (2010) argue that the relative anthropological neglect of dreaming is just one example of the ethnographic privileging of public, daytime experiences over private, night-time experiences. However, if dreams have received relatively little anthropological attention, daydreams and reverie have received even less.

I did not study the daydreams and reveries of research scientists in detail (to do so would have necessitated a different methodology). What I am interested in here is how reflecting on daydreaming in the forest can reveal something about researchers’ relations with and within it, and offer a new dimension to sylvan thinking – or perhaps, to sylvan thought. The distinction between the verb and noun is significant. Where ‘thinking’ is often conceived as a cerebral manipulation of information, or a mental process which allows beings to model the world and to engage with it according to their goals and desires, a ‘thought’ appears to have agency of its own – it is something which occurs somewhat spontaneously in the mind.

Researchers spoke of feeling refreshed after an hour’s walk in the forest had allowed their thoughts to wander – refreshed in the way one might feel after waking up from a restful dream. Reverie allows for a kind of ‘wringing out’ of accumulated perceptions and preoccupations – a chance for thoughts, ideas and observations to combine and recombine, and mutate, in myriad configurations. Imagination travels beyond immediate experience, and rather than abstracting a subject from the world, thoughts serve to tighten knots to other places, persons and times. They are imprints of an intra-action, which continue to have an effect even in their apparent absence.

In those moments of connecting with others – of reaching out tendrils of thought to those others – a temporally-stable self becomes difficult to pinpoint or hold on to. Researchers muse on their future selves – ‘I wonder whether I’ll be interested in that kind of thing at that point in my life?’ – and even their past selves – ‘I don’t know what I was thinking back then’. Selves appear temporally extended, unknowable, multiple. Selves, conceived over time, appear as an internal other, or intimate alterity.5

A self is a term used in conjunction with terms which conjure vitality, wakefulness, perception and reflection, such as ‘consciousness’. When considered the object of introspection or reflexive action, a self often remains beyond one’s grasp. We often conceive of a ‘sense of self’. This sense is distinguishable from other senses because, unlike them, it is proprioceptive and interoceptive, or inward-looking. The exteroceptive senses perceive the outside world, conceived of as ‘other’, while the ‘sense of self’ perceives the self – or, through introspection and reflection, labours to grasp the self. This is often edgework, especially when the self is conceived temporally.

In order to theorise a ‘sense of self’ across time, and to recognise its relationship to the forces of capitalism, colonialism and biopower, social scientists often work with the concept of subjectivity, which is as much a process of socialisation as it is a process of individuation. Taking a phenomenological approach to subjectivity, I find it useful to conceive of it with reference to ‘emplacement’, which suggests the sensuous interrelationship of body-mind-environment (Howes 2005: 7), and to the ‘sensorium’, which Jones (2006 in Myers 2015: 21) describes as ‘the changing sensory envelope of the self’.

Researchers recognise their ‘future selves’ and ‘past selves’ as somehow absent and other, while simultaneously connecting their ‘present selves’ to other times and places. Sometimes, they conceive of this as a kind of oscillation between their ‘field selves’ and their ‘at-home selves’. Several researchers described to me that they consider themselves to enter a kind of ‘fieldwork mode’ when they are in the field. This ‘mode’ comprised a ‘very different state psychologically’, one where people described being able to focus on one objective, and not having other distractions, or one in which they became more patient and resilient, less affected by discomfort and less disheartened by setbacks, even despite the blisters, insect bites, hunger and aching muscles that researchers describe. Entering this embodied and psychological mode was seen as essential to becoming a ‘good fieldworker’; robust, single-minded and with a newly developed somatic awareness and muscular consciousness which enabled them to find, follow and identify bonobos (Alcayna-Stevens 2016).

In paying attention to descriptions of this ‘mode’, one can better appreciate the contrasts made between field/forest and home, which were not only about differences in the environment, but also differences within the researchers themselves. I find Bourdieu’s (1977) concept of ‘secondary habitus’ illuminating for thinking about these newly acquired modes. While the primary habitus is the set of dispositions one acquires in early childhood through familial immersion, the secondary habitus is, in the words of Wacquant (2014: 7), ‘any system of transposable schemata that becomes grafted subsequently, through specialized pedagogical labor that is typically shortened in duration, accelerated in pace, and explicit in organization’. The habitus which field scientists cultivate in pursuit of bonobos is embodied and all-consuming, but temporally and spatially bounded. Selves are tied to place and activity, both of which redefine the landscape of an embodied being and its ‘sense of self’.

Introspection sits uneasily with the scientific method and has largely been discredited in favour of empiricism – and, in the human and animal sciences, behaviourism.6 The deeper one looks into oneself, the logic goes, the further one recedes from external others, and from the world. According to much euroamerican conceptualisation, thoughts reach out to the world, but seldom connect with it – at least, not symmetrically. For example, when researchers think about friends or family, or when they think about bonobos, this shapes their thoughts and feelings about these others, but it has little impact on the ways in which these others think about them – even if it will ultimately have an impact on the relationship. And yet, within these meandering thoughts, researchers nonetheless knot themselves to other places, times and beings.

Indirect

Her thumbnails flat against the front of her shoulders, her thumbs holding the straps of her bag slightly away from her body, she almost jogs the final few hundred meters. Then, something catches her eye in the leaf litter, slightly up ahead and to the left. She trots over and squats down to examine the broken foliage: The blackened stems of an arrowroot plant.

During her first few weeks in the forest, it is unlikely she would have noticed the pale green stems among the foliage and leaf litter. Now, these and other signs jump out at her, strike her, even when she is not looking for them. Even when she is lost in her thoughts and not actively paying attention to the path ahead.

She turns the broken stem over in her hand, trying to assess how long it has been on the ground. It is the stem of an arrowroot plant of the genus Haumania, often grouped together with others of the Marantaceae family as ‘terrestrial herbaceous vegetation’ (THV) when primatologists note down bonobo feeding activities. Bonobos break open the stems with their teeth and eat the tender pith within, discarding the fibrous remains. The sap, visible now in its blackened end, turns both their teeth and their urine a dark shade of red.

The stem is flaccid and desiccated – it isn’t fresh. It must be from at least a few days ago. It is unlikely that this ‘trace’ will lead her to the bonobos. She keeps walking.

Finally, she reaches a large fallen tree which runs alongside the path, its roots upturned, now sprawling and branching out like a toppled crown of antlers. She recognises the tree and takes out her GPS to orient herself relative to the Dialium tree she intends to visit. She must walk northeast at 32°. She orients the arrow on the compass and adjusts her position so that she is facing the same direction as the needle. She steps off the path and begins walking through the forest, stepping over and under tangled vines, and around saplings and larger foliage.

As she approaches the Dialium tree, she feels her heart sink a little. The bonobos are not here. She takes off her backpack and lies down on the ground, using it as a headrest. She lies back on the log, looks up at the canopy, glinting with movement in the afternoon light, and concentrates on what she can hear: insects, a bird, the sound of a branch cracking and leaves rustling in the distance. She focuses on that sound, turning her head, straining to hear through the hum of insects. She makes out the sound of chattering monkeys accompanying the rustle of leaves and branches. She turns back to the glimmering canopy.

Her mind begins to wander again. She is somewhere else, and the forest is present only when the faint breeze from an insect’s wing grazes her cheek. Then, suddenly she hears a chorus of calls – ‘high hoots’ – in the distance, and sits bolt upright. She orients her compass. The bonobos are at least 700m away, but she may catch them if she is quick.

If a certain scientific single-mindedness characterises researchers’ ‘fieldwork mode’, it cannot be said to characterise every moment spent in the forest. Much of that time is also spent in absent-minded reverie. I would like to linger on this absent-mindedness, in order to think both about the nature of scientific labour, and about the limits of knowing.

The researchers were seldom to be found anthropomorphising, ‘egomorphising’ (Milton 2005) or attempting to speculate on bonobo desires, intentions or thoughts during their data collection. Following their research protocol, they noted down observed feeding and social behaviours, without commenting on intent or emotion. They did, however, egomorphise indiscriminately when attempting to find lost bonobos. They would spend hours, both collectively and individually, speculating and hypothesising about where the bonobos could be, and why they might be there. Were they tired? Were they waiting for a ‘preferred’ fruit to ripen? Were they avoiding, or looking for, certain members of the community?

There was much debate about how best to find bonobos. Should one look simply in the area one last saw them? Or should one target fruiting trees and other areas which might interest bonobos? Should one move around the forest searching for them? Or should one wait in a single place? All researchers agreed that whatever strategy one chose, ultimately one would have to rely on the senses, and the secondary habitus one had developed while conducting fieldwork. Their eyes, ears and noses were ready to be ‘caught’ by bonobos and their traces. They had learned to be affected by the subtlest of signs, and this did not require focus, but rather a broad openness to the possibility of bonobos’ presence, even in their absence.

Researchers did not find bonobos through pure chance. They would discuss strategies and fan out across the forest in the areas they felt (sometimes through reasoning, sometimes because they had a ‘gut feeling’) they were most likely to find bonobos. But these strategies just as often failed as succeeded, and in order to be open to bonobos and their traces, but not frustrated by the endeavour, researchers’ gazes were often broad and undirected, relying on their senses to pick out what was considered important to attend to. To be undirected is to be counter to the scientific method. However, like introspection, it is a strategy which field scientists employ to greater or lesser effect when searching for their study subjects. Absent-mindedness emerges, then, as an important tool for sanity and success in the field.

Beyond this functionalist analysis however, absent-mindedness can also serve as a way of thinking about the kinds of labour entailed in ‘edgework’ or ‘cuspwork’. Critical studies originating in psychoanalytic and feminist theory postulate the ‘gaze’ as a ‘one-way event that denies the agency of the perceived object’ (Kaplan 1999: 57). With their emphasis on embodied, material and relational approaches, feminist scholars have stressed the reciprocal adjustments and ‘attunements’ (Despret 2014) required of scientists and their animal ‘subjects’ or ‘objects’ during encounters and ‘cohabitation’ (Haraway 2003). What interests me here is not the stories of communication and ‘copresence’ in primate research from which Haraway (2008: 76) draws inspiration. In the absence of bonobos, field primatologists often search for, come across, and follow signs. However, these signs are not messages, they are indirect and noncommunicative: traces of vegetation, knuckle prints, faeces, abandoned nests. Like thoughts, they allow field scientists to reach out to bonobos. But while they entail a rapprochement, they do not always connect.

To conceptualise these asymmetries, I would like to pause on Haraway’s (2016) suggestion that the insatiable hunger of living beings for each other often ends with indigestion. I am interested in the limits of knowledge and understanding, in asymmetry, non-rapport, nonrecognition and indifference. The gaze is a metaphor of agentive asymmetry. I would like to suggest another asymmetrical metaphor in order to explore scientists’ relationships to the forest – one which moves away from the ocular and lingers on the embodied and the indeterminate.

‘Grasp’ is evocative for a number of reasons. Firstly, unlike the eye, which is not a specialised organ of perception (beyond being able to detect colour) in humans and other primates, the hand and its dexterity are perhaps the most significant adaptation which defines the primate order. To survive, young primates must be able to grasp their mothers. Almost everything a primate eats passes through her fingers, and much of what she touches (including when she grooms her friends and neighbours, solidifying their social bonds), she touches with her hands. Grasp, of course, has another meaning beyond seizing and holding something. It also refers to mental activity, to comprehending something firmly and fully. Grasp can be used to conceptualise the limits of knowledge and comprehension precisely because it allows something to sit within one’s perceptual range, without being fully understood.

In conclusion

This chapter has focused not on conventional tools of scientific knowledge-making, but on the moments in which researchers search the forest for lost study subjects. It is during these interstitial moments that the background of field research, the forest, comes to the fore and captivates the researchers’ attention, opening up the possibility for different kinds of thought. These modes of thought, which are embodied, undirected, uncertain, introspective and indeterminate, are typically overlooked in social studies of science.

An attention to thought perturbs both a commitment to the empirical and a commitment to the social. I have argued that attending to such thoughts can challenge assumptions about the kinds of labour required to do scientific research. The field is important here, because scientists cannot control as much as they might in the lab, and their study subjects are always at liberty to evade them. Indeed, labour in the field extends beyond data collection, cleaning and analysis, and involves the embodied and perceptive skills required to find and follow bonobos (Alcayna-Stevens 2016). It is in this context that introspection and absent-mindedness emerge as important tools for sanity and success in the field. Similarly, while uncertainty and indeterminacy may be anathema to the explanatory goal of science, wonder and curiosity are the seeds of the scientific endeavour.

Beyond this functionalist analysis, I have drawn inspiration from feminist geographies and studies of science and sought to untether thought from communication and semiosis. Using an ‘absential logic’, Kohn (2013: 74) expands the definition of a sign – typically an object, quality or event whose presence or occurrence indicates the presence or occurrence of something else – into an embodied framework in which the elongated snouts and tongues of anteaters can be described as interpretations of the geometry of ants’ tunnels. Interested also in absences and traces but inspired by feminist approaches to ‘indeterminate bodies’ (Waterton and Yusoff 2017), I would argue that an ‘ecology of selves’ might best be conceived as an ‘open whole’ precisely because other selves cannot be determined from the outset (see Cadena 2014). Selves must be discovered. And even once discovered, they remain unstable (they can disappear or die) and unpredictable.

Where Kohn seeks a unifying theory, an embodied and emergentist understanding of semiosis which would move anthropology beyond the human, ‘sylvan thinking’ leads me to linger on those moments when meaning fails to cohere and when understanding appears beyond one’s grasp. Yusoff (2013: 225) argues that ‘that which makes us comfortable reinforces the boundaries of the human, rather than exposing them’. Tracing along the edges of scientific labour, of field scientists’ wandering bodies and wondering thoughts, and the limits of ethnographic fiction, I have sought to argue that it is the imponderabilia, the unanswerable, the unfathomable and the indeterminate which is so compelling when thinking with and in the forest. It is significance without sign. The political and ethical dimensions of this argument point to the vital importance, in an era of environmental crisis, deforestation and mass extinction, of action not being premised on rapport and recognition, but on an appreciation and respect for alterity, asymmetry, indeterminacy and the unknowable.