10

The division of biometric labour: Relations of production in African voter-identification technologies

Cecilia Passanti

Since the turn of the century, digital technologies have played a growing role in public administration around the world. This is particularly visible in Africa where, in response to allegedly dysfunctional public services and inefficient identification frameworks, digital systems are being mobilised in many areas of state-citizen interactions (Breckenridge and Szreter 2012). Biometrics, understood as ‘identifying people with machines’ (Breckenridge 2014), is one of the most vivid illustrations of this trend. Biometric identification based on computer systems was initially used to match fingerprints taken at a crime scene with criminals already known to the police system (Cole 2009). Under the impetus of the incumbent technology manufacturers and in collaboration with increasingly computer-savvy governments, these systems have since been applied to a wide range of sectors, including border control, healthcare, and government subsidies management, as well as the production of certified machine-readable documents. In addition to this, the biometric industry provides computerised voter-list management, voter verification, and other systems to facilitate and expedite the voting process, such as voting machines and results transmission systems (RTS). Biometrics in voting is designed to make voter identification more efficient by capturing voters’ biological data, namely their fingerprints and facial images. These data feed a digital list, stored in a database, which a generic biometric software programme called Automated Fingerprint Information System (AFIS) uses to compare the data in order to detect and eliminate the records of any citizens registered twice. Through this software processing, biometrics is supposed to produce more reliable lists of citizens and thus more trust in public institutions.

Although biometrics are used worldwide for elections – or for democracy, as vendors and experts often put it – they are mostly developed in and for Global South contexts, particularly Africa. Whereas many activists, journalists, and researchers see the entry of biometrics into the field of elections as an attack on the ethics of democracy, many African countries – 36 out of 56 (Debos and Desgranges 2023) – have adopted and engaged in a long-term relationship with this technology precisely to strengthen democracy. Biometrics’ reciprocal love of African governments makes these systems relevant artefacts for the study of the North-South relations embedded in global technological products, and for understanding how they fuel their spread on a global scale.

Biometric identification systems are generic artefacts that move from one context to the next, across organisations (e.g., from forensic to voting) and geographic areas (e.g., from country to country) without losing their nature. They are tremendously adaptable, and their qualities can be reshaped according to local needs. While this adaptive capacity may point to the relevance of studying how identification systems adapt to local contexts (localisation and adaptation work), this chapter takes a different approach, focusing on the production (Pollock et al. 2007) of both generic biometrics and more specific electoral biometrics.

Building on debates about globalisation and postcolonial STS, I argue that the North-South relationship is inscribed in the history of the invention of electoral biometrics and reproduced in contemporary relations of production, namely the division of biometric labour. This concept refers to the structured organisation of work to produce electoral biometric artefacts, which involves the daily work of institutions and individuals at both national and transnational levels. The division of biometric labour functions as a travelling model (Behrends et al. 2014), based on work to produce genericity (Pollock et al. 2007), that supports biometrics’ ability to adapt to disparate contexts. The literature has argued that the genericness and globalisation of science and technology are achieved through work to detach them from their original social relations of production (Akrich et al. 2011). In contrast, I argue that globalisation arises from the reiteration and objectification of their original social relations of production.

The questions guiding this research stem from a debate about the role of Africa, colonial, and postcolonial situations in the emergence of biometric sciences and technologies. Breckenridge framed the African origins of biometric sciences and the resulting statistical-mathematical model of governance (Breckenridge 2014, 2018). Recent studies of biometrics in Africa, however, tend to emphasise the external nature (essentially non-African) of the biometric industry and its technologies. This chapter is driven by the need to recalibrate these findings and to reinscribe digital biometric systems into their terrain of production. How are the production relationships between public institutions, African software engineers, and foreign private suppliers organised and structured? What kind of social relations are the production relations of biometric systems? Why do these systems look so much alike and at the same time seem to mimic and reproduce the style of local government? What kinds of digital labour are implied by the efforts of public administrations to develop biometrics? Answering these questions first means recentring the production of the technology at the heart of African administrations, and thus to open a space for ethnographic observation, from a situated position, of both local and global relations of development. Second, it means considering production relations as a whole part of social relationships.

The chapter draws on three main sources: first, ethnographic observation of the workflows and production context of election technologies in Senegal and Kenya, carried out in Dakar (February–September 2017) and Nairobi (February–September 2019); second, interviews with executives, administrators, agents, and incumbent officials about the production of the technology; and third, interviews with biometrics industrial actors, vendors, and managers on and off site. The chapter reframes the African origins of biometrics (Breckenridge 2014), introducing new data on the organisation of digital labour and the role of voting in the emergence of global biometrics.

Global technologies and their field(work): Extending the STS debate to voting technologies

Since its early days, STS has focused on how scientific knowledge, in addition to being a deeply local object, manages to travel with unique effectiveness to other contexts and spaces (Anderson and Adams 2008; Ophir and Shapin 1991; Shapin 1998). Through the study of the production of scientific facts (Star 1983), work contexts (Latour and Woolgar 1979), and devices/objects created (Latour n.b.), researchers have highlighted the role of scientists’ work in making local knowledge a universal science. In so doing, they have sought to understand how people, through salaried, organised, and structured activities, successfully disconnect objects of knowledge from their immediate relations of production, escaping locality, and enabling them to integrate the social relations of other places and times (Akrich et al. 2011). As STS has globalised (Dumoulin Kervran et al. 2018), a growing number of studies have sought to understand how the Global South is redefining globalisation and technology. These terrains provide a vantage point to grasp the ‘interconnected processes that drive science and technology’ (Rottenburg, Schräpel, and Duclos 2012) that redefines globalisation as longstanding and informal circulations of people, goods, and markets (Choplin and Pliez 2015). Postcolonial studies of STS have argued that the (post)colonial geography and moment are conducive both to the genesis and development of scientific knowledge (Schiebinger 2005) and to the economic-industrial development of the former colonisers (Hecht 2004; Inikori 2002). Many Western sciences – especially medicine, biology, natural history, and botany – are now understood as sciences originating from a postcolonial context (Seth 2009). Other studies are rewriting the African history of technology (ceramics, ironwork, architecture, biometrics, nuclear energy, radiography, etc.), illustrating the shortcomings of the technology transfer narrative (Twagira 2020), reframing science and laboratories through open spaces – the forest, the plantation (Mavhunga 2014) – and thus restoring the roles of African actions, actors, institutions, and territories in innovation (Mavhunga 2017; Mika 2021; Osseo-Asare 2019).

Breckenridge wrote the South African history of biometrics technology and government (Breckenridge 2014, 2018). However, the contemporary literature on biometrics tends to portray it as a Western product, purchased and used by African countries following a pattern of technology transfer. Studies have investigated the diversion and appropriation of technologies by local actors (Beaudevin and Pordié 2016; Do Rosario and Muendane 2016), how controversies repoliticise them (Debos 2018; Salem 2018), how governments use them as state-building tools (Piccolino 2015; Rader and Périer 2017), the modernist imaginaries they convey (Cheeseman et al. 2019; Debos 2018), the injustices they produce (Amoah 2019; Eyenga et al. 2022), and how they affect electoral controversies (Emmanuel et al. 2019; Passanti 2021), reshaping the circulation of public knowledge on voting (Passanti and Pommerolle 2022). By focusing on the life of voting technologies after their production, this body of literature conveys a representation of biometrics as a ready-made product, the result of neutral production relationships occurring in an industry far removed from African soil and devoid of historicity.

Debos and Desgranges (2023) have shifted the debate to what takes place prior to voting, investigating the postcolonial dimensions of the biometrics market. The authors argue that European companies have positioned themselves in African markets since the 2000s, and that they maintain this position through political and economic business networks. In this chapter, I offer an alternative reading of how social relations are reproduced in and through technologies. This approach seeks to reintegrate the historical and contemporary African contribution to the biometrics industry—dating back to the 1970s—while acknowledging the North–South relations embedded within it. Drawing on lessons from both STS and the social history of elections on the objectification of social relations within technology (Garrigou 1993; Kelty 2008; Von Schnitzler 2013), the work of Pollock and colleagues (2007) on capturing the diversity of generic software packages, and that of Behrends and Rottenburg (2014) on travelling models, I propose the concept of division of biometric labour. The division of biometric labour consists of a formal – but not fixed – structure of work relationships between people and institutions coming from and holding together cross-cutting realities (North/South, production/use, private sector/government) for the production of electoral biometrics. The concept posits social relations of work as a historically consolidated structure that enables their reproduction, and it offers a new perspective to rethink the (horizontal) globalisation of technology without overlooking (vertical) North-South relationships and the role of the South in innovation.

Voting technologies and their generic biometric core

Senegal and Kenya, located respectively at the western and eastern ends of Sub-Saharan Africa, do not share the same colonial history, do not face the same issues surrounding voting and government legitimacy, and organise elections in strikingly different ways. Indeed, Senegalese elections are managed by a directorate under the Ministry of Interior, while Kenyan elections are managed by an autonomous electoral commission. Beyond these differences, both countries manage voter identity through an identification system based on biometrics. Senegal’s Ministry of Interior digitises citizen voter identification through a digital working infrastructure aimed at providing voter ID cards. When I conducted my fieldwork in 2019, the system was supplied by a Malaysian digital solutions company, IRIS Corporation Berhad, which had won the government contract. A local IT-services provider, Synapsys Conseils, worked with IRIS to ensure the day-to-day management of the technology. IRIS received the government contract money and subcontracted a portion of it to fund Synapsys’ work. IRIS handled the delivery of equipment (computers/servers, smartcards, laser printers to engrave data on the cards, etc.), the troubleshooting of serious problems at server and printer level, and remote system support.

Synapsys was primarily responsible for designing the system, adapting it to local needs and language, developing new applications required to manage the electoral roll, designing the data entry interface, and training police officers in the use of the database. These activities take the form of a structured, institutional network of continuous daily work activities, carried out by police officers with varying degrees of digital skills, ranging from data entry clerks to IT engineers and managers (see Figure 10.1).

Fig. 10.1 The system administrator of the biometric citizen database of Senegal, Dakar, biometric ID card server room observation, Ministry of Interior, April 2022 (Cecilia Passanti)

The IT department of Kenya’s electoral commission, on the other hand, has developed a network of tablets at polling stations connected with central datacentres, which allow for biometrically registering voters, electronically identifying them with their fingerprint before they vote, and transmitting election polling results to the central database for publication (see Figure 10.2). The voting process is almost entirely digital, with the exception of the voting itself, which is paper- and polling booth–based. During my fieldwork in 2017, the technology was provided by Safran Morpho, a well-known and longstanding French digital-identity solution provider. The IT directorate of the election commission was involved in daily technology production, managing the voter list database, recording equipment features and needs, maintaining the digital infrastructure for voting, training polling officials, and tallying up digital votes at the national tallying centres.

Fig. 10.2 Civic education video clip depicting two officials biometrically verifying the identity of a voter at a polling station, Nairobi, Kenya, May 2017 (Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission)

As different as these technologies are, they share significant similarities, especially in terms of the organisation of the work involved in their production. Both rely on the work of a third party, a foreign technology provider specialising in biometric solutions, Safran Morpho in Kenya and IRIS in Senegal, that supplies the material infrastructure and delivers it on the ground. In both cases, after delivery, the technology is assembled, maintained, and produced in the field through a structured organisation of biometric work performed by public IT departments, managers, administrators, and thousands of civil agents involved in collecting, processing, and cleaning biometric data. These similarities suggest a formalised working structure that can manage and integrate the variety of different administrations.

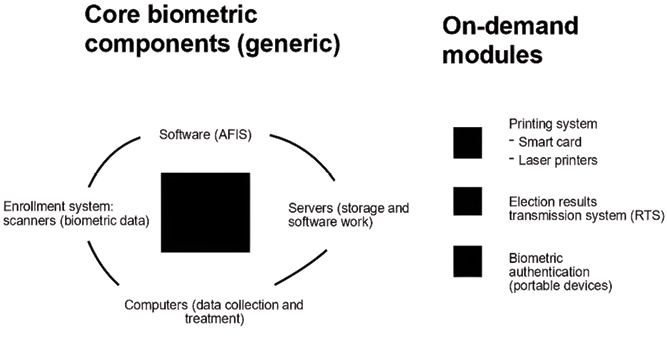

Moreover, both technologies rely on a core structure of materials and software which are essential to any biometric system, namely the enrolment system, biometric scanners, the biometric software programs (AFIS), computers, and servers (see Figure 10.3). Some of these core components – especially the AFIS and the scanner to capture fingerprints – are mostly produced and sold by incumbent industrial manufacturers (such as Safran Morpho and IRIS). Vendors add on-demand modules to these core components based on local government requirements. For example, Senegal, which issues ID/voter cards, requires a ‘printing system’ that consists of a physical room in a protected environment, where civil servants print citizen data on biometric smart cards using biometric laser printers, and organise the delivery of the cards to citizens. Kenya, on the other hand, which transmits results digitally from the polling stations to the national tallying centre, requires an ‘election result transmission system’ that consists of an additional application embedded in the biometric tablet.

Fig. 10.3 A generic biometric identification system, which has a basic core to which the government can add modules upon request (Cecilia Passanti)

Biometric production relies on the design and formalisation of generic models of biometric identification systems that exist only on a theoretical level, on websites and at vendor booths. This generic structure is the result of the itinerant history of biometrics, guided by an economic model that aims to multiply markets to amortise high production costs by connecting to different organisational and geographic contexts. One of these was the African countries’ quest, which occurred at the time of independence, for the material conditions of access to representative democracy. The administration of voting and governance, subject to the injunction of the development aid regime, was the terrain of several technoscientific inventions, including civil biometrics.

The travelling history of biometrics: Genericness and the software’s African trajectory

In the 1970s, fuelled by police departments’ search for scientific methods to identify criminals, biometrics developed into a flourishing computer industry. Between the 1970s and the 1990s, the years during which African countries were achieving independence from colonial rule, biometrics were increasingly articulated with government identification systems in both the Global North and the Global South. Safran Morpho, one of the world’s leading players in the industry, was created in the 1980s, under the name of Morpho Systèmes, by French investment funds and a research network based in Dakar (Senegal). The birth of Safran Morpho is closely linked to the history of access to independence and the spread of democracy in African countries.

In Africa, the colonial enterprise had imposed severe limitations on access to citizenship (Cooper 2012; Lonsdale 2016; Manby et al. 2011; Medina-Doménech 2009). This translated into a lack or non-existence of census systems for African citizens, and existing records were kept and maintained primarily in the metropole. The lack of registries became critical in the 1960s and 1970s, a period when the newly independent countries were to hold their first elections to establish their first independent government and thus establish their sovereignty over their people (Cooper 2012). In Senegal, the tension between the needs of the independent state and the absence of a solid identification system prompted the search for technical solutions, which was taken up by a group of engineers from the École des Mines in Paris, with the support of a French public bank (Caisse des dépôts et Consignations) and a French technology transfer provider working in French-speaking Africa (Sinorg). After the departure of the French administration, Sinorg computer scientists intervened within the ministries of the newly independent countries to support the administrations in the management of tasks, especially relating to taxation and the payment of public wages (Zimmermann 1984). The Sinorg experts, who were specialised in computer science for public administration, were also French-speaking African administration experts: they travelled from country to country to provide their technical support. They were thus able to recognise a cross-cutting issue faced by several African countries around the question of voter identification, which spurred the idea of investing in a technology company to solve it. The people involved in this early biometric project attested to the creation of Morpho Systèmes at the request of Senegal and more specifically Senegalese heads of state – first Léopold Sedar Senghor and then Abdou Diouf. Sinorg’s CEO started hiring experts, especially French experts working with Senegalese computer scientists from public administration, to think about the use of biometrics and to constitute the voting list for the 1983 elections. Until then, biometric computing had been limited to criminal identification.

The shift of biometrics from forensics to civil services represented a real scientific and technical challenge. In its early days, biometrics was limited to police identification systems that worked with much smaller databases, containing only already-registered criminals and not the entire civilian population of a state. It was precisely to overcome this challenge that Morpho Systèmes was founded and heavily funded to research and produce a ‘machine for African civil identification’. Using Senegalese fingerprints and databases, building on the ‘African need’ for voter identification, the first prototype of biometric voting – the Système Opérationnel de Saisie et d’Interrogations d’Empreintes (SOSIE) – was born in Dakar.

The electoral biometrics project in Senegal failed due to lack of sufficient funds. The government had disinvested and Sinorg’s own investment was coming to an end, necessitating the signing of a new contract to continue the research. Neighbouring countries that had heard about the project, first and foremost Cameroon, funded the project for several years: in 1983, the government signed Morpho Systèmes’ second contract to supply the first system (in the world) for producing national ID cards based on biometric identification of citizens. Traveling to Cameroon, the company had the opportunity to implement anew the working model on which the first Senegalese system was founded: an organisation of production that straddles the international supply of hardware and digital materials and a daily anchoring to the work of the local public administration. The production of ID cards is a long-term process, based on the daily demands of citizens, which takes place nationwide. Production is based on citizens’ data collection, and it is not possible to produce it outside the field. Nor is it possible to produce it in a purely local way because much of the knowledge and materials on which it is based (in the same way as many information systems) is not present locally. The contract with Cameroon has provided Morpho with the necessary capital to continue research and development activities for several years. In addition, the establishment of a database of Cameroonian citizens has provided a development ground on which to improve the efficiency of the technology.

Besides these few early markets, the clients of biometrics for citizenship (voting and identity card production) were not enough to sustain research and development. Morpho thus returned to the forensic Western market, developing technical principles learned on the African field. The idea was to come back to the African market later on. The capacity acquired in Africa, however, had allowed Morpho to become a global leader – a position it still maintains. The company has signed contracts with other actors in other organisational settings and spaces, for example, two contracts for social security delivery in Florida and South Africa. Moreover, in the 1990s, the company was able to sign a contract to supply technology to the US FBI. The FBI market is the greatest reward for biometrics companies. Winning it means having a powerful and globally competitive algorithm in front of American and Asian companies. In each of these different contexts, the company has provided biometric identification systems through a production model situated between the global digital hardware market and the specific needs of local governments in different countries around the world.

The African context, especially that of Senegal, was mentioned by managers and engineers as the terrain that allowed them to think, mobilise sources, articulate needs, and experiment with the technique underlying the new technology. The Safran Morpho founder illustrated this role:

The invention of biometrics for voter registration arose from a need expressed by Léopold Senghor, President of Senegal, and from SINORG’s search for a solution. Personally, I believe it was a co-invention of Senghor – Senegal – and the CEO of Sinorg. I was the one who made possible and realised what was only a dream.

The African contribution to the invention of electoral biometrics and of this new notion of biometrics for citizens (civil biometrics) is often stressed by Morpho founders and colleagues.

The birth phase of civilian biometrics occurred in the postcolonial era, as part of a research and development relationship between France and Senegal. The production relationships of the first prototype, traveling to various countries and contexts, became enduring and were structured into a production model that I now describe. It is based on a flexible structure of work activities that always remain the same but have a capacity to anchor themselves in the work of local administrations. Production relations keep the birth act of civil biometrics alive.

Contemporary relations of production as social relations

As in the birth phase, the production relationships of biometric voter and citizen identification systems involve a set of work activities at the crossroads between national and transnational levels, local government and foreign technology providers. These relationships can be found in different countries, as I have observed in Kenya and Senegal, which suggests a travelling model of production. The production and implementation of biometric voter identification systems requires a set of work activities that I now disentangle.

The first type of activity relates to biometric software production. Software is often described as the beating heart of biometrics and as its most significant component because the deduplication of citizen files in the database depends on it. While software production is mostly an industrial activity, it does not take place outside the field. Biometric technology manufacturers secure their position by signing contracts, managing projects, and engaging in relationships with public administrations. Field experience is key to the development of biometric technology, as software production and performance rely on the availability of databases of real peoples’ fingerprints. Moreover, variations in climatic and/or biological conditions dramatically influence the algorithms’ performance. Predicting which kind of data can be obtained in the field is a very important form of expertise, as the Safran Morpho founder shows in the following interview excerpt:

In a business there is technology and experience; technology without experience or experience without technology are worthless. For example, after a long plane ride, Bedouins during the dry season, Asian women and their small fingers make fingerprinting an extremely difficult and technical task. The software wonders if it has the characteristic points needed to calculate a score. If the fingerprints are very dry or small, the detection proves complicated and can lead to situations where you do not have enough characteristic points to compare the images. Once the problem is understood, solutions such as administering dry finger cream can be suggested.

Information about fingerprinting behaviour in a given population allows a company to know and learn about the efficiency and general behaviour of its own software. Each time a company signs a contract and implements its system in the field, it discovers different aspects of the efficiency of its algorithm in a specific context. This experience helps vendors overcome typical technical and administrative problems (Zviran and Erlich 2006) and thus supports the ability of biometric systems to better cater to an ever-wider range of social and environmental realities. Incumbent and longstanding software manufacturers have accumulated several more years of experience with African public administration, cultures, environments, and fingerprinting behaviours than other vendors. They are therefore more highly rated by African governments and in a better position to be chosen to carry out subsequent projects. Biometric software production and efficiency strongly relies on available datasets, and thus on citizens’ personal data and on the ability of the company to be in the field.

Another set of production activities is referred to as system integration (SI). While incumbent technology providers can be or act as SI providers, the integration work can also be done by the administration’s IT department and/or African IT companies. This is because being a system integrator involves dealing with oversight, the actual implementation of the technology in the field, and its material composition (integration for short), in order to make it a functional system. Integration is about knowing and cultivating relationships both with companies on the global biometrics market and with African administrations. These two types of relationships are referred to as ‘partnerships’ because they are built on mutual appreciation, trust, and win-win deals. Social relationships are the key feature of this marketplace: they are nurtured and cultivated through travel, visits, long-term friendships, knowledge exchange, advice, and trust. Power relations and hierarchies between actors need to be studied ethnographically at this level.

System integration involves three main activities. First, contract design consists of drafting specifications of technological requirements and qualities, for example, the number of devices required and their material shape. This activity is conducted in Africa by local IT departments, often in collaboration with international – often African – experts, and sometimes with technology vendors. The design and technical requirements of the system are established based on the election management software and products available. Second, the actual system integration occurs soon after the contract between the SI provider and the election institution or the government is signed. At this point, the SI provider calls on global partners (digital hardware and software vendors) to purchase the components they need in order to assemble an ‘election system’ (computers/servers, cameras, database management systems, biometric scanners, biometric printers, and biometric software). This horizontal network of peers allows vendors to purchase components from suppliers from around the world, to find the best price, or to form a long-term partnership. Third and lastly, implementation or adaptation to the local context consists in ensuring the effective operationality of technology that is customised to local needs and demand. Only once the contract is signed and the various parts have been purchased from the market is the generic technical design transformed into an existing technological object with extremely local qualities. The actual birth of a biometric election system only occurs at this stage, through an adaptation process that can take years. Adaptation involves adding the modules required by the contract, designing the technical system as such, adjusting data formats to other existing computer systems, adapting to local legislative requirements, tailoring machine programs to local programs, producing graphical interfaces for interaction with the database and biometric data (data entry and processing interface) accessible to officials (thus translating the system and interfaces into the language of the country), producing video demonstrations of the technology tailored to the local culture (with African rather than Caucasian actors, for example), and organising local management of distribution, shipping, and support. Incumbent software vendors have accumulated not only experience in the field of African public administration, but also partner relationships and knowledge of the global digital biometrics market. This allows them to always have the best prices on the market and therefore to continue to win contracts.

African public administrations are key actors in biometric production of technology systems and biometric data. This expertise materialises within a structured organisation of work. For example, since 1980, police officers with IT degrees attest their work with computers and databases. Since the 2000s, a private Senegalese technology provider named Synapsys Conseils has been working for the Senegalese Ministry of Interior for IT management of information systems. This makes the company a longstanding repository of knowledge on how public and administrative information systems work. The relationship between Synapsys and the ministry is a commercial one: the company is hired for a particular project, which it carries out with a group of employees that can vary in size. The relationship between the administration and the company is daily and informal, given their longstanding collaboration: the company has several offices where employees spend their days supporting the work of officials (police officers) whom they know well as people and employees. Similarly, in Kenya, the IT directorate of elections management employs a dozen IT staff that manage information systems before and after the arrival of biometrics.

The literature on contemporary voting technologies often treats local IT vendors and departments as intermediaries for bribes between the administration and foreign biometrics companies. However, these local actors are chiefly engaged in the day-to-day work of developing, implementing, and maintaining the technology. From an ethnographic perspective focused on observing daily activities, the work of the foreign companies is reduced to brief regulatory interactions when compared to the continuity of the relationships between administrators, managers, and machines that play out every day in administrations. These vignettes illustrate how foreign companies’ interactions with African public administrations are intermittent and fleeting, and how they rely on local employment. They also highlight how production and maintenance relationships are most often peaceful relationships between human beings working together to make things work.

Nairobi, a few months before the 2017 elections

In the waiting room of the Kenyan Election Commission’s IT director, I hear the voices of a group of men with marked French accents: a delegation from Safran Morpho has arrived in the field. Sitting on the same couch as me, a gentleman speedily types away on his laptop. I look at him several times until his gaze meets mine. ‘Are you from Safran Morpho?’, I ask him. He is the project manager of the French technology provider in charge of training local staff to use biometric tablets. He has to teach two main trainers, who will then go on to train both constituency-level IT support staff (140 people) and polling station staff (45,000 agents at voting offices). The company has rented a large shed on the outskirts of Nairobi and employed a hundred Kenyans to recharge the tablet batteries and put them inside the 45,000 backpacks to be sent to the voting offices. The company also employs a dozen Kenyan computer scientists, who represent the company on the ground. The delegation consists of three executives, directors, and the head of training. They will return to Paris next week after performing several demonstrations of the technology before election stakeholders.

Dakar, a few days before the 2021 elections

A delegation from Synapsys Conseils, the Malaysian company, is in Dakar in the field: a female director, two managers, and two technicians. The IT director of the public administration suggested that I meet with a member of the delegation at his office at the ministry. After a few minutes’ wait, a very young Malaysian support engineer, tired from the Dakar heat and fasting for Ramadan, joins us. The two engineers can barely pronounce each other’s names, but there is a strong shared understanding between them, certainly founded around computer science and perhaps their fasting fatigue. The Malaysian delegation is leaving today, after a nine-day stay in West Africa. The company normally intervenes remotely, but following a major technical problem with the ID-card servers in Guinea Conakry, right on the border with Senegal, the team took the opportunity to come to Dakar to solve minor problems and speak with the authorities.

Foreign companies’ interventions in the field rely on quick actions by small delegations. Beyond the sending of materials, interventions can be technical (technology training, troubleshooting), organisational (recharging and distribution of machines, public demonstrations), or political (company executives interacting with the leaders of local institutions). These interventions consist of social relationships aimed at establishing a functional biometric system but also a market relationship, based on trust and long-term partnerships between the company and the administration. The speed of projects is counterweighed by the need to maintain a strong presence on the ground, to ensure the continuity of the daily support that technical systems require in order to function. My intention, in emphasising the work of local IT, is not to minimise the work of biometrics companies surrounding product ideation, supply, shipping, transfer, and so forth. However, as they are not based in African countries, the companies work remotely and rely on local IT organisations to implement projects.

Last but not least, biometric voter identification systems require the extensive mobilisation of human resources by local governments. In both Senegal and Kenya, the number of civil servants required to collect, verify, process, and transmit biometric data is impressive and organised into workflows, starting with enrolment to register voters and process requests for ID documents. While the directorate overseeing elections in Senegal relies on the permanent employment of police agents as well as some temporary agents, the Election Commission of Kenya employs temporary agents to enrol voters several months before an election takes place, in order to be able to use the biometric tablets to identify voters on the polling date and to send the results for tallying. During elections, these groups of people, numbering in the thousands – 400,000 in Kenya and 100,000 in Senegal – register and verify millions of voters across the country – 15 million in Kenya and 17 million in Senegal – for several hours a day and over several months. This group of people is framed as users of biometric technologies. However, this label does not aptly describe the capital role of their work in the production of biometrics. During voter registration, civil servants actually produce the main component required for the identifier systems to function: the biometric data. Other teams of civil servants (in Senegal mostly women hired on short-term contracts) use computers to cleanse the data collected in the field and prepare them for inputting into the database. Before the data are actually entered into the database, the biometric software compares each incoming file with those already registered, validates unique requests, and blocks duplicate files by suspending them for verification by a human agent.

A team of police investigators is assigned to verify suspicious files. By analysing the data shown on the biometric software users’ interface, investigators work to clarify the reasons why a citizen has made a duplicate ID request. The biometric software has automated and thus reduced some of the work carried out by police investigators to identify suspicious cases, but this work is not replaceable. The more suspicious cases the software identifies, the more human work is required to verify the suspicious files. The fewer cases it identifies, the less human work is required, but the more the system will issue identities to people requesting an ID card without them actually having the credentials required. After the citizen files have been processed by the software and the police investigators, they are sent for printing, a process referred to as the printing and distribution system. This system is managed by a team of police officers who work with computers, smart cards, and biometric laser printers within a printing room organised into several laboratories. Groups of officers specialise in one function and perform their respective roles, passing the baton to the next group once they have completed their tasks: launching the print files from the central computer; confirming the printing jobs; inserting blank cards into the printers; collecting the printed cards; verifying the data on each card against the computer’s digital data; packaging a batch of cards; and dispatching the delivery to the administration on the ground. While card production volumes normally amount to 2,000 cards per day, a few months before the election, the demand for documents begins to increase, and productivity becomes a real democratic value – the more cards are delivered, the more people will be able to vote – and card production reaches volumes ranging between 40,000 and 70,000 cards per day.

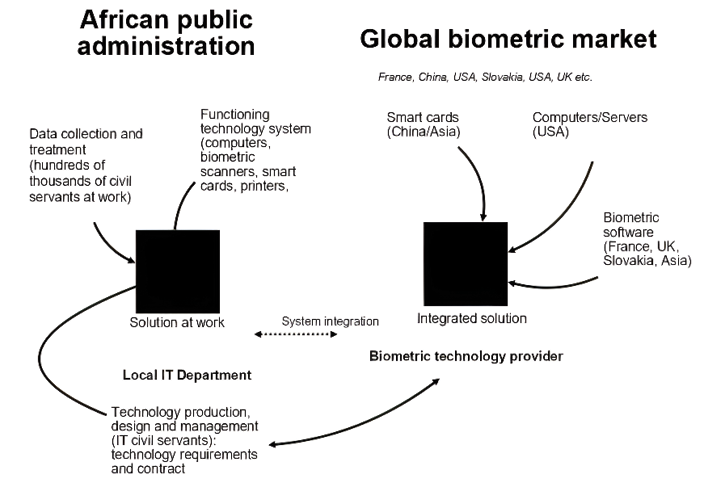

The analysis of production relations attests that at each stage of technology production, actors have social and collaborative relationship at the crossroads between national and transnational levels, local government, and foreign technology providers. Labour relationships serve as a catalyst for such diverse realities as government and technology providers, the nation-state and the global digital marketplace, the public and private sectors, and the South and the North. These relationships hold together complex artefacts such as ID systems and enable them to travel. While the North-South relation can be very important in the production of electoral biometrics, it is not necessary. It can morph into Asia-Africa relations, as is the case in Senegal, and, depending on government choices, it can morph into an African government that resorts independently in the global digital market. What really matters and cannot be replaced is the working model that links the global approvisioning market for digital materials to the biometric work of public administration. This working model can be found in different countries and settings and is summarised in Figure 10.4.

Conclusion

The African trajectory of global biometrics and the contemporary relations of production of biometric-based voting technology offer a new perspective on the ability of this technology to spread around the world.

Biometric technologies – both electoral and generic – appear as open, constantly evolving systems that have specialised in dealing with different organisations and fields. This specialisation has been integrated within the structure of production. In the two countries where I observed them, biometric-based voting technologies are built on a complex organisation of work that involves the daily labour of both national and transnational institutions and people. These relations of production are organised in a formal structure that I call the division of biometric labour. This structure was born in Africa, particularly Senegal, at the time of independence, through a network of North-South (France-Senegal) research and development relations. The history of electoral biometrics explains why these technologies are so adaptable to African democracies and to postcolonial countries that share a similar history surrounding civil identification. Thus, not only has African countries’ quest to ensure the material conditions of democracy played a key role in the creation and spread of biometrics in the Global South, but it has also played a key role in the growth of the industrial and global biometrics project itself, pushing biometrics out of the forensic sector and into the civilian sector.

Fig. 10.4 The division of biometrics labour between African public administration and the biometric market (Cecilia Passanti)

The chapter documents an aspect that is often underestimated in studies of globalisation as it is too often understood only through the notion of ‘value chain’: labour relations in the fabrication of technologies cannot be reduced to unfair labour organisation. Following that line of inquiry, the chapter shows another dimension of the globalisation of technology as experienced from Global South countries, one which relates to role circulation and market expansion through work relations. In biometric science, technology, and industry, genericness and globalisation are not achieved through detachment work from the original social relations of production. On the contrary, genericness and globalisation are achieved through the original act of invention, based on the North-South relationship of innovation (the ‘birth stage’ [Pollock 2007]). Moreover, they are achieved through the reiteration of these original social relations of production over different places and spaces. The reiteration of production relations allows for their specialisation and structuring; it enables them to objectify into a hard core of technology production relation. These production relationships make biometric technologies, which are vast technologies based on large-scale administrative infrastructures, travel with a ‘unique efficiency’ (Shapin 1998) and become a global presence.

References

Akrich, M., M. Callon, B. Latour, and A. Monaghan, ‘The Key to Success in Innovation Part I: The Art of Interessement’, International Journal of Innovation Management, 6.2 (2011): 187–206 https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919602000550.

Amoah, M., ‘Sleight Is Right: Cyber Control as a New Battleground for African Elections’, African Affairs, 119.474 (2019): 68–89 https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adz023.

Anderson, W., and V. Adams, ‘Pramoedya’s Chickens: Postcolonial Studies of Technoscience’, in E. Hackett, O. Amsterdamska, M. Lynch, and J. Wajcman, eds., The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies (MIT Press, 2008), pp. 181–204.

Beaudevin, C., and L. Pordié, ‘Diversion and Globalization in Biomedical Technologies’, Medical Anthropology, 35.1 (2016): 1–4 https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2015.1090436.

Behrends, A., S.-J. Park, and R. Rottenburg, Travelling Models in African Conflict Management: Translating Technologies of Social Ordering (Brill, 2014).

Bierschenk, T., and J.-P. Olivier de Sardan, ‘How to Study Bureaucracies Ethnographically?’, Critique of Anthropology, 39.2 (2019): 243–57 https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X19842918.

Breckenridge, K., Biometric State: The Global Politics of Identification of Surveillance in South Africa, 1850 to the Present (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Breckenridge, K., ‘État documentaire et identification mathématique: La dimension théorique du gouvernement biométrique africain’, Politique africaine, 152.4 (2018): 31–49 https://www.cairn.info/revue-politique-africaine-2018-4-page-31.htm?contenu=resume.

Breckenridge, K., and S. Szreter, eds., Registration and Recognition: Documenting the Person in World History Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Cheeseman, N., G. Lynch, and J. Willis, ‘Digital Dilemmas: The Unintended Consequences of Election Technology’, Democratization, 25.8 (2018): 1397–1418 https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2018.1470165.

Choplin, A., and O. Pliez, ‘The Inconspicuous Spaces of Globalization’, Articulo – Journal of Urban Research, 12 (2015) https://doi.org/10.4000/articulo.2905.

Cole, S., Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2009).

Cooper, F., ‘Voting Welfare and Registration: The Strange Fate of the État Civil in French Africa, 1945–1960’, in K. Breckenridge and S. Szreter, eds., Registration and Recognition: Documenting the Person in World History (Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 385–412.

Debos, M., ‘La biométrie électorale au Tchad: Controverses technopolitiques et imaginaires de la modernité’, Politique africaine, 152.4 (2018): 101–20 https://www.cairn.info/revue-politique-africaine-2018-4-page-101.htm.

Debos, M., and G. Desgranges, ‘L’invention d’un marché: Économie politique de la biométrie électorale en Afrique’, Critique internationale, 98.1 (2023): 117–39 https://www.cairn-int.info/journal-critique-internationale-2023-1-page-117.htm.

Do Rosario, D. M., and E. E. Muendane, ‘“To Be Registered? Yes. But Voting?” – Hidden Electoral Disenfranchisement of the Registration System in the 2014 Elections in Mozambique’, Politique Africaine, 144.4 (2016): 73–94 https://www.cairn-int.info/journal-politique-africaine-2016-4-page-73.htm.

Donovan, K., ‘The Biometric Imaginary: Bureaucratic Technopolitics in Post-Apartheid Welfare’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 41.4 (2015): 815–33 https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2015.1049485.

Dumoulin Kervran, D., M. Kleiche-Dray, and M. Quet, ‘Going South: How STS Could Think Science in and with the South?’, Tapuya: Latin American Science, Technology and Society, 1.1 (2018): 280–305 https://doi.org/10.1080/25729861.2018.1550186.

Emmanuel, D., E. John, and I. Owusu-Mensah, ‘Does the Use of a Biometric System Guarantee an Acceptable Election’s Outcome? Evidence from Ghana’s 2012 Election’, African Studies, 78.3 (2019): 347–69 https://doi.org/10.1080/00020184.2018.1519335.

Eyenga, G. M., G. O. Omgba, and J. F. Bindzi, ‘Être sans-papier chez soi? Les mésaventures de l’encartement biométrique au Cameroun’, Critique Internationale, 4.97 (2022): 113–34 https://www.cairn.info/revue-critique-internationale-2022-4-page-113.htm.

Garrigou, A., ‘La construction sociale du vote: Fétichisme et raison instrumentale’, Politix. Revue des Sciences Sociales du Politique, 6.22 (1993): 5–42 https://www.persee.fr/doc/polix_0295-2319_1993_num_6_22_2042.

Hecht, G., ‘Colonial Networks of Power: The Far Reaches of Systems’, Annales Historiques de l’Electricité, 2.1 (2004): 147–57 https://www.cairn.info/revue-annales-historiques-de-l-electricite-2004-1-page-147.htm.

Inikori, J. E., Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England: A Study in International Trade and Economic Development (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Kelty, C., ‘Towards an Anthropology of Deliberation’, Society for Social Studies of Science Annual Meeting, Montreal, 2008 http://kelty.org/or/papers/unpublishable/Kelty_Anthro_of_Delib_2008.pdf.

Latour, B., ‘Notes sur certains objets chevelus’, Nouvelle Revue d’Ethnopsychiatrie, 27 (1995): 21–33 http://www.bruno-latour.fr/fr/node/228.html.

Latour, B., and S. Woolgar, Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts (Princeton University Press, 1979).

Lonsdale, J., ‘Unhelpful Pasts and a Provisional Present’, in E. Hunter, ed., Citizenship, Belonging, and Political Community in Africa: Dialogues Between Past and Present (Ohio University Press, 2016), pp. 17–40.

Manby, B., H. Bazin, T. Vedel, and C. Becker, La Nationalité en Afrique (Karthala, 2011).

Mavhunga, C. C., Transient Workspaces: Technologies of Everyday Innovation in Zimbabwe (MIT Press, 2014).

Mavhunga, C. C., What Do Science, Technology, and Innovation Mean from Africa? (MIT Press, 2017).

McLaughlin, J., P. Rosen, D. Skinner, and A. Webster, Valuing Technology: Organisations, Culture and Change (Routledge, 2002).

Medina-Doménech, R., ‘Scientific Technologies of National Identity as Colonial Legacies: Extracting the Spanish Nation from Equatorial Guinea’, Social Studies of Science, 39.1 (2009): 81–112 https://doi.org/10.1177/03063127080976.

Mika, M., Africanizing Oncology: Creativity, Crisis, and Cancer in Uganda (Ohio University Press, 2021).

Ophir, A., and S. Shapin, ‘The Place of Knowledge: A Methodological Survey’, Science in Context, 4.1 (1991): 3–22 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0269889700000132.

Osseo-Asare, A. D., Atomic Junction: Nuclear Power in Africa After Independence (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Passanti, C., ‘Contesting the Electoral Register During the 2019 Elections in Senegal: Why Allegations of Fraud Did Not End with the Introduction of Biometrics’, Jan Thorbecke Verlag, 48 (2021): 515–25 https://doi.org/10.11588/fr.2021.1.93969.

Passanti, C., and M.-E. Pommerolle, ‘The (Un)Making of Electoral Transparency Through Technology: The 2017 Kenyan Presidential Controversy’, Social Studies of Science, 52.6 (2022): 928–53 https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312722112400.

Piccolino, G., ‘Infrastructural State Capacity for Democratization? Voter Registration and Identification in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana Compared’, Democratization, 23.3 (2015): 1–22 https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.983906.

Pollock, N., R. Williams, and L. D’Adderio, ‘Global Software and Its Provenance: Generification Work in the Production of Organizational Software Packages’, Social Studies of Science, 37.2 (2007): 254–80 https://doi.org/10.1177/030631270606602.

Rader, A., and M. Périer, ‘Politiques de la reconnaissance et de l’origine contrôlée: La construction du Somaliland à travers ses cartes d’électeurs’, Politique Africaine, 4.144 (2017): 51–71 https://www.cairn.info/revue-politique-africaine-2016-4-page-51.htm.

Rottenburg, R., N. Schräpel, and V. Duclos, ‘Relocating Science and Technology: Global Knowledge, Traveling Technologies, and Postcolonialism. Perspectives on Science and Technology Studies in the Global South’, Max-Planck-Institut für Ethnologische Forschung, 19–20 July 2012 https://www.hsozkult.de/event/id/event-68318.

Salem, Z. O. A., ‘“Touche pas à ma nationalité”: Enrôlement biométrique et controverses sur l’identification en Mauritanie’, Politique Africaine, 152.4 (2018): 77–99 https://www.cairn.info/revue-politique-africaine-2018-4-page-77.htm.

Schiebinger, L., ‘Forum Introduction: The European Colonial Science Complex’, Isis, 96.1 (2005): 52–55 https://doi.org/10.1086/430677.

Seth, S., ‘Putting Knowledge in Its Place: Science, Colonialism, and the Postcolonial’, Postcolonial Studies, 12.4 (2009): 373–88 https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790903350633.

Shapin, S., ‘Placing the View from Nowhere: Historical and Sociological Problems in the Location of Science’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 23.1 (1998): 5–12 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-2754.1998.00005.x.

Star, S. L., ‘Simplification in Scientific Work: An Example from Neuroscience Research’, Social Studies of Science, 13.2 (1983): 205–28 https://doi.org/10.1177/030631283013002002.

Star, S. L., and K. Rudleder, ‘Steps Toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces’, Information Systems Research, 7.1 (1996): 111–34 https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.7.1.111.

Twagira, L. A., ‘Introduction: Africanizing the History of Technology’, Technology and Culture, 61.2 (2020): S1–S19 https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.2020.0068.

Von Schnitzler, A., ‘Traveling Technologies: Infrastructure, Ethical Regimes, and the Materiality of Politics in South Africa’, Cultural Anthropology, 28.4 (2013): 670–93 https://doi.org/10.1111/cuan.12032.

Zimmermann, J.-B., ‘Politiques africaines de l’informatique’, Politique Africaine, 13 (1984): 79–90 https://www.persee.fr/doc/polaf_0244-7827_1984_num_13_1_3688.

Zviran, M., and Z. Erlich, ‘Identification and Authentication: Technology and Implementation Issues’, Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 17.4 (2006): n.p.