1

Imagining

Classrooms

I am nervous. This is to be my first day in a classroom ‘doing research’, and I’m not sure what it’s going to mean. I dress carefully; make sure all my forms and ethics clearances are in my bag; check again for my notebook. When I arrive at school, I find the right classroom and my teacher. I chat, trying to seem competent. When the bell rings, I am seated at the teacher’s desk. I have to stand, surprised and flustered when he asks me to introduce myself to the kids. Why hadn’t I predicted this was going to happen? I tell them who I am, and blunder through an explanation of what I’m doing here, what I’m going to be looking at. Geez, if I find this difficult to explain to children, how am I going to explain it in a book?

This perhaps makes me sound foolish, blundering. Researchers are supposed to know what they are doing; planning experiments, writing methodologies, organising teams. But in the social sciences, and likely in any sphere working with human participants and seeking qualitative information, the rules are not clear (Law 2004). One simply cannot know exactly what one is looking for until one finds it. This is a version of Meno’s paradox: roughly, how can I search for knowledge about something if I do not know anything about that something? To solve it we need a theory of knowledge that admits to imperfect knowledge (Dillon 1997: 1–2). We have to blunder a little. But at the same time we need to be able to tell our participants which parts of their lives we are hoping to take for our texts. And so we strike a paradox: I am expected to be certain about what I am looking for (seeking a specific truth), but the unfamiliarity of the community of practice I find myself in demands that I be flexible, open, and responsive to what is there.

I was able to be in these classrooms only because I had successfully given an account of what I was going to do and what I thought I might learn. These are a requirement of ethics procedures, of which I completed three – for the university, the state government, and the Catholic education office. On these forms, I said I would do ethnographic fieldwork for three weeks each in five grade four classrooms, or until I believed I had done sufficient research to stop noticing new things; conduct an audio-recorded semi-structured interview with the teacher; and ask that the children draw and write about ‘a time they used their imaginations’. Explaining why this was an important topic, I had written about empathy and creativity. These were what I thought I might find. They were also what I thought would sound like persuasive rationale to primary school principals and teachers.

I presented these sure methodologies and serious-sounding rationales to schools. I gained access to some classrooms by ringing up or visiting school principals and others by following personal networks. I found that principals were hard to make contact with, but once they were on the end of a phone line or across a desk, they were decisive: very often interested but running too busy a school to wish for researchers. If they did agree, we entered into a process of negotiation over issues such as which teacher might be interested and suitable. Would I like to work with an experienced or a new teacher? On several occasions it seemed very obvious to the principal who would be best for me to work with: some teachers are understood by the principal, and indeed across the school, as being ‘good at imagination’. For the principals in these discussions, it was the teacher who is the classroom.

At the end of these negotiations, I found myself in various classrooms. All were for grade four or three/four children. They were not necessarily the ones I would have chosen. They were the effect of who I asked and how I presented myself. They were the effect of how far I could travel. They were the effect of the stresses of running a school; of a principal’s sense that this could be interesting or useful to their teachers; or their belief that there was already a teacher who would show their school to be a richly imagining place. Each classroom was located in a different type of school: independent (or private), government (or state), Steiner (or Waldorf), Catholic, and special (for children with low IQs). They were located in different areas around Melbourne, from inner to outer city, in demographics that ranged from very wealthy to very poor (see Fig. 1). However, they were not, and never could be, representative of ‘primary schools in Melbourne’. There are too many schools, divided across too many types of category. Each school, just like each individual, is uniquely situated in the wider social world. The schools I discuss, then, provide a range, not a sample.

Fig. 1 Map of Melbourne to Show School Locations

But where am I? And what am I to do there?

This chapter is an attempt to answer these questions rephrased in the more general terms of ‘what is a classroom?’ and ‘How should we think of the appropriate behaviours for a participant-observer?’ Here I explore two answers to these questions. One set of answers presents classrooms as parts of a whole, and the other presents classrooms as complex assemblages. In giving each answer, I provide a description of these five classrooms. Importantly, each also differently directs what a participant-observation researcher should do in a classroom.

Readers might wonder how I can give two answers. Which one do I think correct? My suggestion is that the two answers are two ways of performing the analytic work of theorising. Perhaps more clearly, they are ‘modes of ordering’ done by your author. ‘Modes of ordering’ is the term used by sociologist John Law. They are what Law argues we use all the time in our physical, material, and discursive performances of reality. They are modes of relating subjects and objects in ways that are provisional and potentially multiple. They are what we perform with every time we engage with the world, including when doing qualitative research. Law explains that

[T]hey are all of: stories; interpellations; knowing relations; materially heterogeneous sociotechnical arrangements; and discourses. This is because they run through and perform material relations, arrangements with a pattern and their own logic. Except […] they are smaller. More contingent. Putatively less consistent, less coherent (Law 1994; Law 2000: 23).

I will suggest here two modes of ordering that I believe structure our engagement with classrooms, though it is laborious to become aware of these. Both were available to me when I entered classrooms and they remain available as I work to make sense of classrooms – as were many others. Now though, I can choose which is the best for my intervening. I choose to work with two, not because I think there are only two, but because I find them useful for thinking.

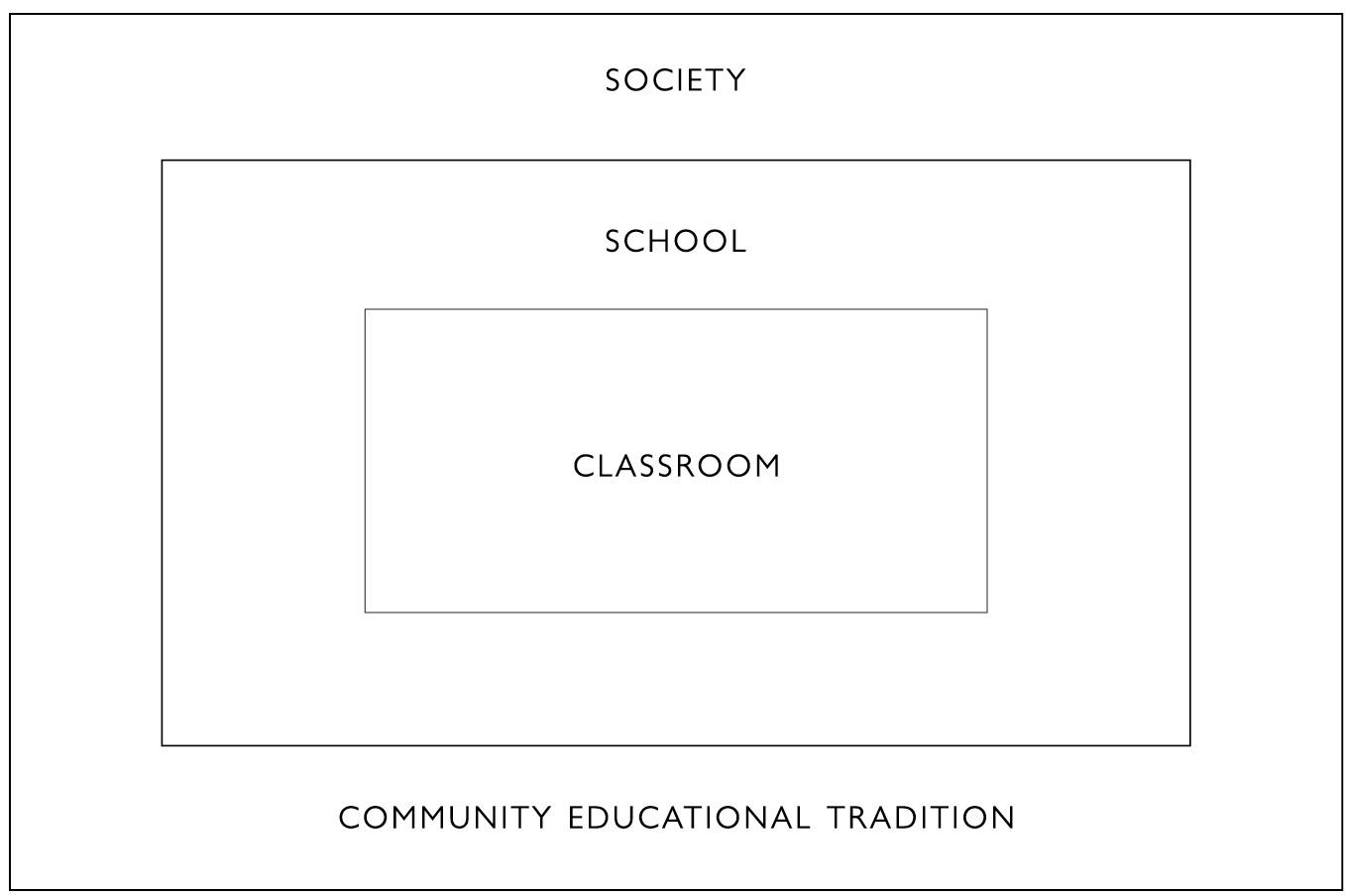

One mode takes classrooms to be nesting within schools, and schools nesting within ‘society’ (see figure 2). In the first part of this chapter, I will try out a particular version of this idea using the work of Kieran Egan. But I will go a bit further. Instead of representing society or community or values, I will argue schools work hard to present and build an ideal (future) society within their own grounds. Pictured this way as bounded communities, the participant-observer should act as a respectful contributing member of these societies and their values. Giving up their own prejudices, they should seek to represent classrooms as isolated social fields within the broader field of society. This is a mode of ordering that makes classrooms part of schools which are part of society’s ideal possibilities. This mode of ordering also makes researchers into those who are to report on, or perhaps judge, these ‘societies’. To some extent this is how I acted in classrooms, and it forms part of what I do in writing. But I also follow a second mode of ordering.

Fig. 2 Diagram to show classroom nesting in school nesting in educational tradition

This second mode takes classrooms to be assemblages of classed and classing bodies. Here I use the word ‘class’ to identify two important features of the persons gathered in a classroom and school. These are (1) that they are part of the wider social hierarchies of wealth, culture, and future potential, and (2) that they are bodies who are learning to classify their worlds in particular but everyday ways.1 To draw together these two features, I speak of classed and classing bodies. When researchers, with their own classed and classing bodies, come to participate and observe in such places, they experience harmonies, clashes, and interruptions to their bodies. Their own values, springing from their belonging to a particular class, are mobilised. This impacts on how they are able to observe and participate. More, because their abilities to classify are tied to aspects of their class identities, they might find their descriptions of what was going on difficult to return to the academy. This mode of ordering makes classrooms sites where classed and classing bodies interact in harmonious and disruptive ways. This makes the researcher’s subject position as one who works the uneven ground between classrooms, cultural and socio-economic class, and their own modes of classifying.

I tell about classrooms in both modes of ordering because both are useful for different purposes. The first tells readers the types of things they are accustomed to hearing about a couple of schools, educational traditions, and demographics. They serve to fit the classrooms into a way of ordering the world that we are familiar with. Using school information and marketing materials, the researcher represents classrooms as they seem to represent themselves. I tell the second because I believe it speaks more accurately and more ethically about what it is to do classroom research.

What is a Classroom?

Answering within the School-society Nexus

At the start of this chapter I found myself in a classroom. One answer I can provide to explain where I was is to say a classroom is a nesting part of a school and the school a nesting part of society. This seems quite natural: it is after all how we are used to thinking of our individual identities as persons in families that are in communities that are in cities that are in nation-states. Using this picture of classrooms we would ask about how they are related to society: to what educational traditions do their schools subscribe? How are they situated in terms of the demographics of wealth and social values they represent (and attract parents with)?

This initially would seem to claim something quite simple: that a Steiner classroom, for example, represents the values of the Steiner community. This needs to be complexified, for most classrooms represent a mixture of values that have been transmitted through time. The work of Kieran Egan will help us do so.

The school-in-society picture is one Egan implicitly uses in his book, The Educated Mind (1997). He tells of a way to pull apart the complex threads that make up educational traditions and goals. By a deep and rich understanding of (Western) society’s hopes for schooling, Egan suggests that all schools represent some mixture of three aims. These are about what people are (and should be), and since agglomerations of people will form societies, these aims also evidently picture what society is (or should be). However, according to Egan, these three aims are inconsistent and this has created an insoluble problem for education. Only by developing a new vision of what learning is might schools escape this morass; or this is how he introduces the theory he articulates throughout this book.

Egan provides a way of distinguishing the educational aims that, he argues, (though inconsistent) guide schooling. These are (1) the aim to socialise children so that they will be good citizens of the society and polity; (2) the aim to provide the child with accurate and objective knowledge of the world around them; and (3) the aim to let children develop their individual human potential. Does it make sense to think of children educated to live as Christians developing objective knowledge about the world? Or to think of children learning to be objective and accurate but also happy to follow arbitrary social conventions? All three conflicting goals, he suggests, are present in all our schools in some mixture, with one generally appearing dominant (Egan 1997, especially chapter one).2

I introduce Egan here to help us see clearly how some schools represent themselves and understand their distinct educational goal. For example, according to their own advertising material, Steiner Schools are described as aiming for the third objective outlined by Egan, which is developing the individual human potential of each child in spiritual and intellectual terms. As the Steiner School advertising flyer puts this, ‘we aim to provide the right nourishment at each stage of physical, emotional and spiritual growth’ and ‘strive to allow children to fully experience the joys and mysteries of childhood’ (Anonymous undated, ‘Steiner School’).

This goal does nest nicely within the values of particular segments of society. The words quoted above were printed on a flyer that interested parties are encouraged to pick up from a box outside the school gate. This gate is located in an arts precinct, so while the foot traffic is light, it is also made up of a specific self-selected demographic – those likely to already be interested in community organisations, personal artistic expression, and a politics of non-conformity with state and capital. These are values this flyer appeals to. The learning that children will experience at this school is to be ‘enlivened by an artistic way of working and a focus on observation to educate the whole human being’. This is education that does not ‘espouse merely materialistic values’ but aims to form ‘young adults who can think, judge and act freely and responsibly’ (Anonymous undated, ‘Steiner School’). This in turn is a clear vision of an ideal society of persons who are holistic and artistic in their understandings, more spiritual than material, and freethinking.

But though Egan’s theory of schools representing aims of society can be useful and expresses a conventional way to think about classrooms, I believe there are problems with it. If schools represent conflicting ideals, then representing more than one becomes a problem. Schools become confused. But if we think of schools as doing these values, conflicting as they might be, we become more able to deal with multiplicity without accusing anyone of confusion. We can easily believe in doing one thing and then another. For example, in the Government School advertising, all three of Egan’s goals are told as important. Overall, the booklet gives the sense that Government School has created itself as a place so much like a good and happy society that children will naturally become socialised, will learn, and develop as individuals by their time there. What we see is these three goals integrated in such a way as to claim to make the ideal society in the present and for the future.

This point about the ‘ideal society’ is important. I suggest that Egan’s three aims might be logically inconsistent, but even when combined they make sense within particular visions of ideal ‘societies’. By identifying a school’s aims we can see just how they position themselves within society and what changes they hope to initiate in the social future. This is to say that we should extend Egan’s account and render the school-society nexus in terms of how a school represents itself as (re)producing an ideal present and future society. Classrooms are not just a part of society, but are working to remake society. This is evident in the ways schools advertise themselves.

This, I believe, makes an important methodological and ethical difference. In Egan’s account, educators and parents seem confused advocates of incoherent positions on what schools should do. By my account, educators and parents educate in ways that are coherent and sensible in order to achieve what they take to be the ideal potential society their children should inhabit. What they represent to parents, carefully and thoughtfully, is a vision where all three of Egan’s goals – socialising, knowledge uptake, and individual development – may in various ratios naturally occur together. Some schools emphasise the social, and others the individual, but all give some weight to all three.

So this is one solution to the question ‘what is a classroom’ – it is a unit within a school that in turn is a unit within a particular vision of society (and aiming to produce or reproduce this vision). A classroom represents and enacts a vision of an ideal future. In each, the classroom researcher is to participate as if within a microcosm of (the ideal) society. They are part of that specific culture. As such, they are to contribute to a complex of behaviours that enact meanings and beliefs. These meanings and beliefs are then to inform their description of these classrooms as ethnographic worlds. They are to represent that classroom fairly and fully. I have suggested that this extends the account of the school-society nexus presented by Egan. But we can give a better account of what a classroom is. It is better not for descriptive purposes, but for developing an ethical sociology of education. I pursue this alternative answer now.

What is a Classroom? Untangling the Knot of Class

I have said above that a class can be thought of as nesting in a school and in an educational tradition. But nestled within the word ‘class’ are several other meanings. Class is a broad term referring to social and economic relationships; it is about group membership and identity; also it is about making groups, classifying. These associations are built into the language that we use, and as I will argue here, they are also built into the material life of classrooms.

Here I explore the term ‘class’ in order to build an ethico-political account of classrooms. To some extent this is a literal-minded approach. It is also animated by a conviction that already in the language we use are metaphors that guide our (re) constituting of our world. Rather than assume that there is some term that lies underneath all classrooms, we should better understand the words that are used in and about classrooms. Instead of searching beyond our sites of enquiry for metaphors to describe those sites, we should talk critically in the language that is used. Remembering that as a noun ‘class’ denotes socio-economic groups, questions of membership and its denial, and hierarchies of cultural and financial power, allows us to speak of classes of children in particular schools as already marked by these socio-economic distinctions. They already have classed bodies. ‘Class’ is also a verb. ‘To class’ is to put into groups, categories, typologies, or hierarchies. Learning to class or classify – to segment the world in particular ways – is one of the key tasks of primary school children. They are learning to have classing bodies.

Hence, one answer to the question ‘what is a class?’ is that it is a structured group of classed and classing bodies. This is a material answer, but with it comes an ethical consideration for the researcher.

As researchers we also have classed and classing bodies. We attend or work in universities or government agencies. We have particular cultural capital, social status, and relations to governance. These relations class us in complex ways. Moreover, we are adept at making knowledge by grouping or classifying information. We do not pass the government and university ethics committees that regulate classroom research without the necessary signs of these academically classing bodies. But, when we do enter classrooms, we might find ourselves among a class of people we feel uncomfortable with, socially, intellectually, or physically. We might also find that our ability to classify is inappropriate to the classroom, for teachers might act in ways that we have not been taught to classify or been taught to classify unfavourably. We might find that our classed and classing body is challenged in new ways. We have responsibilities to the children and teachers we research, but in these challenges to our own class and classing, we feel threatened, confused, or compromised. Or, equally dangerous to those we intervene with, we might find our judgements of good or bad seem all too self-evident.

I pursue ‘class’ then as a hinge that joins the socio-material relations in classrooms and the ethico-cognitive responsibility of classroom researchers. I start by telling a story about an interaction with a child rewritten into the language of class relations. This shatters what seemed to be a commonplace moment in the relations between child, peers, and researcher to reveal conflicts between classed and classing bodies. Next I turn to questions of what we do and what we should do with metaphors. I work with Haraway’s notion of the heuristic ‘knot’ (2004). This explains ‘class’ as useful because its constituent strings lead to the apparently diverse, but in fact closely connected, elements I am interested in. These are the connections between social and material position and the ‘right’ to know. These are knots that tie up the researcher just as much as the classrooms they research. In the third section I explore some times when my researcher’s classed body responds in powerful corporeal ways to the classrooms I visit. Reactions of this kind must have some implications for participant-observation research. This is a moment of reflexive confession. It opens up, however, into more theoretical concerns in the fourth section. Here I explore what happens when ways of classing and being classed clash or interrupt when a researcher enters a classroom. Using Kathryn Addelson’s notion of double participation, I ponder the question of how to represent events when they exactly challenge the skills of classifying sanctioned by the university.

Classed and Classing Bodies

Mr. Robertson marks the books immediately after the spelling test. Sitting at his desk, he calls out that Michael got all fifteen words correct. I’m standing by the wall, beside two children, a boy and a girl, who have been seated in front of their teacher’s desk for the rest of the year. Referring to Michael, the boy says to me, ‘he spells like a fifteen-year-old’. His own book is given back. Having read his score he continues, ‘I spell like I’m seven years and two months. I’m the worst in the grade’. Like the other children in this room, he is aged nine or ten. He explains further: ‘It’s because I came from a different school. I’ve only been here a few months, since the start of the year. It was a really bad school, just a government school’ (Author field notes, Independent School, 16 March 2007).3

On my first day in this classroom, this boy named Jayden helps me become aware of the social and material orders that exist here. For him these are visible through the relative talents of the other students. As he talks he places himself in several classes at once. He tells me he is in the class of seven-year-old spellers. He is part of the cohort of his age and grade, but in the position of worst. And he classes himself as (having recently become) part of this school, and thus part of the socio-economic relations that make this a ‘good’ school. From this new position, he is able to say his old school was bad because it was government funded.

While he makes these relationships real through the words he uses, his relations to the others in the class are also being made through material arrangements. Seated up front with only one other student (instead of in a group of four or six as the rest of the class are arranged), he is set apart. He often turns to speak to the boys behind him, to join in conversations or to try to get help with work. Mostly they ignore him but sometimes talk until the teacher tells Jayden to turn around. His uniform is new, but unlike the other kids he wears it messily, shirt untucked, and hair untidily long. He is perhaps saying ‘I know I do not belong (and I don’t care)’. Perhaps it is to make up for these distances from his class that he works for my friendship.

To me he boasts. He has seen me arrive on my bicycle, and tells me that he has two bikes. He describes them and tells me their cost as ‘one thousand dollars or something’. He tells me about the number and type of his parents’ cars. He tells me how much money he has saved: one thousand five hundred dollars. He plans to buy a motorbike. ‘What’s the best university in the world?’ he asks, and says he will go there. These claims about money and future possibilities, he perceives, are the things that impress those who surround him.

Perhaps they do, but they don’t impress me. A government-school educated, middle-class, anti-consumerist feminist, I internally – and sometimes externally – rail against his troubling position of privilege: those cars, this school, that projected future. Over and over at this school I feel resentments welling up inside me that I deal with by thinking patronising thoughts. I am reminded of Bourdieu (see, for example, Bourdieu 1984). These people have economic capital that I, with only cultural capital, sneer at.

I also build interpretations that fix this class as part of the socio-economic system that assigns human value on the basis of owning money and objects. Feeling this system to be unjust, I also feel its reproduction through the institution of this classroom to be unjust. When I find out what the fees are for this place, I am shocked. To be a member of this classroom, one’s parents must be members of another class: those who can afford to pay the equivalent of almost my whole yearly earnings for a year of their children’s education. Doing so, they must believe, will reap significant rewards, financial and otherwise, for their children. Socio-economic class is to be reproduced, though in ways that are not solely financial. These children are to have musical, sporting, and artistic talents. They are to be good citizens and Christians (Gregory undated). They are to have the skills of self-actualisation (Saulwick and Muller 1999). I read these words with a cynicism that says ‘these are the values of the rich’.

But though surrounded at home and at school with the material markers of an exclusive socio-economic class, Jayden does not seem happy. Largely this appears due to his failures to fit, academically or socially, with the rest of his classmates. He is less able than others to perform the cognitive and social acts that will reap positive attention, and he is aware of this. Week after week he does badly in spelling. The words are not chosen at random, however, but because they display a similar phonetic form. The arrangement of English into phonetic groups is mapped on the wall of this classroom in the form of a ‘Thrass Chart’, a literacy education tool developed by Denyse Richie and Alan Davis.4 On it, each phonetic group is put in a box, in an order roughly following the alphabet. Each square contains the letters that make the sound, and the word and picture of an exemplary noun. For example, this week Mr Robertson has chosen words that all contain ‘ph’, a phonetic grouping illustrated on the chart by ‘dolphin’. Jayden, however, is worse than others in his class at recognising the common elements of each word and applying them during the spelling test. Sometimes he puts an ‘f’, sometimes a ‘ph’. What he is failing at is an act of classification; seeing that all these words are related by their common phonetic elements.

He also regularly fails to find the right topics of conversation with his classmates. He tries telling them about his other friends, or about basketball, or about his parents’ cars. Sometimes these gambits work, or work for a while, but eventually he is sent back to his desk or returns there after the other children ignore him or are rude. His categories of good topics of conversation and good social behaviours are not quite right. He gets the most positive attention from his classmates when, usually by mistake, he gets in trouble with the teacher. The line between good and bad behaviours that is supposed to govern this class is not yet clear to him. Social classifications are not yet easy for him to enact.

I decide that I like this child, tacitly applying mental tags that read ‘sweet, but socially inept, needs to work harder to catch up’. These stay attached to him in my mind and in our interactions, and now I write about him emphasising those features that make him this type of figure. In my telling these tags all relate him to class – to failed bids at class membership, socially with his peers, and physically in where he is seated; to the socio-economic class of his parents who have removed him from a ‘bad’ (read poor) school and put him here; to his conversational emphasis on his socio-economic class that fit the discourses of this classed school; to his difficulties in making phonetic classes work for him in his spelling test; and to his classing of himself as ‘the worst’.

I have also told this as a story of my own class and my own classing. Forming an oppositional stance to the material wealth and consumerist values of this school, I tell others and myself about my own middle-class – my university educated, feminist class – my cultural capital. I work this position into my classing of what happens at this school, how I understand and respond to the social and learning practices that occur in this classroom. Recognising this clumping of material and analytic problems provides the motivation to explore the power of the supposedly innocent, but multiply designating, ‘class’.

Class as an Analytic Knot

I want to use ‘class’ as an analytic device that shows the co-joint and inseparable nature of the several notions that the term class denotes. It is a word that, to use Haraway’s notion, acts as a knot (Haraway 1994). We can follow its strings outwards variously to shared and contested group membership, to socio-economic differences embedded in the backgrounds and futures of individuals, and to acts of classifying performed by teacher, children, and researcher. ‘Class’ lets us look in several directions at once. Moreover, ‘class’ is a metaphor that already structures the life of the classroom. Classrooms are so permeated by the metaphor of class that we forget that it is both metaphorically and materially significant to what classrooms are.

Attending to metaphor can illuminate things previously hidden; just what appears depends on the metaphor used. There are two main ways that metaphor has been used in classroom studies. One is to study the language used in and about classrooms to find their common metaphorical centre. This is the technique advocated by Lakoff and Johnson (1980), and applied to classrooms by, for example, Hermine Marshall. In 1988 and again in 1990, Marshall critiqued the use of the metaphors used in classrooms that gathered as ‘classroom-as-workplace’, suggesting that it focused attention on task completion and product creation rather than on learning. Suggesting that ‘classroom-as-learning-place’ would better highlight the processes of learning, she worked to encourage teachers to think and act in ways that encouraged processes instead of products (Marshall 1988; Marshall 1990). If we were to follow this technique we would study language to identify common words used in and about classrooms and study their implications for classroom practice. We would find a metaphor that seemed to sum these up. Metaphor in this work is a tool for naming animating values within classrooms. Doing so, however, fails to recall that classrooms are also material places, assembled with people and things that already have political and social lives.

A second way to use metaphor is to search outside the classroom for things to compare the classroom to. Whereas the first technique would search for metaphors in classrooms, here we would search for good metaphors for classrooms. These will hopefully work to reveal something new about the nature of all classrooms. Working in and for broader analytic concerns, this technique finds suitable metaphors to enhance a particular theoretical approach to classrooms.

This has its dangers, perhaps the most obvious of which is that the metaphors chosen can have practical implications. This is a problem that Keith Sawyer identifies. He shows that the metaphor ‘teaching is performance’ has crucially mis-modelled the nature of teaching in ways that have been fed back into teacher education. He explains that ‘the performance metaphor suggests that an effective actor could be an excellent teacher without even understanding anything’ (Sawyer 2004: 12). This had the effect of denigrating the knowledge and skill of teachers and supporting the writing of scripted lessons for them to simply present to the students. Instead of using the ‘performance’ metaphor, he suggests, we should talk and think of ‘teaching as improvisation’ (Sawyer 2004). This should serve as a reminder that in applying metaphors from outside of schools we must be very careful that they only describe usefully and do not carry theoretical implications that can be damaging.

Perhaps one way to avoid this danger is to follow Helen Verran in choosing metaphors that seem only to describe, and that are too clunky to slip as if naturally into actual classrooms. This is the approach used by Verran when she talks about classrooms as ‘organised/organising micro-worlds’. By this she means ‘specific materially arranged times/places where rituals, repeated routine performances, occur’ (Verran 2001: 159). This is a useful phrase because it contains within it the joint nature of classrooms as structured and productive. Using this term, however, we miss out on the opportunity language affords to call up the actual and the figurative simultaneously. Because it is designed to disrupt our thinking, it is hard to find actual classrooms in the phrase ‘organised/organising micro-worlds’. It is a phrase that could describe almost anything.

Perhaps another solution would be to find metaphors from other scholarly work that are hard to slip into classrooms but that also link us to broader theories. Here, however, it is description of the material reality of classrooms that might be compromised. It is tempting, for example, to talk of classrooms in terms that Edwin Hutchins uses in his study of distributed cognition (Hutchins 1995). His work takes place on a naval ship, and indeed the metaphor of the ‘ship’ works productively to image the process he is interested in. Arguing that we should understand some thinking as going beyond the skin of individuals, he shows how each member of staff on a naval ship is an expert in only parts of the larger routines necessary to sail. The ship succeeds because all staff share conversational routines that powerfully link those routines into one. No one person could know, perform, or control all the routines necessary to bring the ship into port, but through the correct joining of routines the ship is docked.

When applied to classrooms, the ship metaphor does some useful analytic work, highlighting the assembled nature of classrooms, filled as they are with materials and people marked by their lives outside the classroom but for many hours a day isolated together. It makes thinking a group activity, but one that is tightly constrained by relations of authority. The ship metaphor can reveal relations and the power of material objects, but it would also carry dangers because of differences between classrooms and naval ships. Some are to do with authority and expertise. On a naval ship, relations of authority are multi-layered but in a classroom all children are to be subordinated to the teacher. All children are to be roughly equal in expertise, and vastly less experienced and competent than the teacher. It would also misunderstand the aims of classrooms. Taking there to be a clear end point – task completion – that all members of the group share, the ship metaphor makes the work of the classroom into specific, uni-linear, productive processes that would hide the creative, under-determined nature of learning.

Instead of searching for a metaphor used in classrooms or about classrooms, I suggest an approach more like that of Donna Haraway. She explains her work in an interview with Thyrza Goodeve published as the book How Like a Leaf. When asked about her use of metaphors from biology, she explains that for her using the language of biology is to highlight simultaneously the literary and literal nature of biology. ‘I want to call attention to the simultaneity of fact and fiction, materiality and semioticity, object and trope’ (Haraway 2000: 82–83). Hers is an approach that calls us to remember that language and material arrive together.

For Haraway, as for other feminists, the goal of scholarship should not be to describe from a fictional ‘outside’ but to admit our positions within. This is a better way to produce objective knowledge than the pretence of seeing and speaking from nowhere. Maximally objective knowledge is possible only when researchers are critically situated within their objects of study. We share language with those we study, carrying notions taken so much for granted that we fail to notice them or their implications. This implicates the researcher too, reminding us again of the need to be reflexive about how we fit and what we wish to see. As Sandra Harding wrote to advance the claims to objectivity of standpoint epistemology, ‘objectivism impoverishes its attempts at maximising objectivity when it turns away from the task of critically identifying all of those broad, historical social desires, interests, and values that have shaped the agendas, contents and results’ (Harding 2004: 136). The desires, interests, and values come already packaged in our language – that of researchers and participants alike.

Next I explore further this nexus between researcher, language, and situated-ness in classed and classing bodies. What does it mean for doing objective research in classrooms if we are honest about the desires, interests, and values that we carry in our classed and classing bodies?

Ethics and the Researcher’s Classed and Classing Body

At my first meeting to arrange research work at Steiner School, I wear what I consider my most ‘hippy’ skirt. This is a joke made into a material reality. In clothing my body in this way I am announcing my allegiance to and requesting membership in what I assume is the social and political class of Steiner teachers. I am classing them as racially white, politically anti-capitalist, and socio-economically middle-class – hippies. I am showing myself as classed likewise. Certainly, this has some effect on how I am treated; they seem to like me.

My classed and classing body does more than dress up, it feels. After days in the classroom of a government school with a teacher who carefully brings ethics of multiculturalism and mutual responsibility into her teaching, I cycle home feeling deeply happy. Her practice of politics, I feel, touches my heart. Mawkish as this is, it is also sign that her practices of producing relationships between her children and their world gel with my beliefs and aspirations of what schools should do. Her practices meet my expectations as the child of a liberal university education and of the political and social views I have been embedded in. This subject position is again intrinsically part of my classed and classing body, a body that feels as part of its thinking.

Such feelings are not always positive matters of simple connection with others who seem to occupy the same group as oneself. Meeting parents during my time at the special school for low-IQ students, I experience a sense of confused and cruel ambivalence. Many of these parents are evidently low in financial and intellectual capital. They lack teeth, are obese, or wear strange and dirty clothes. I am witnessing the reproduction, literally, of society’s most marginal class. At times I feel this as disgust, a fear of bodies so unlike my own, bodies profoundly marked by their positions in hierarchies of intelligence (and discourses of genetics) and socio-economic status. At other times I experience these moments as guilt for classing and judging others in such terms. This is brought into relief when I meet Roderick’s mum. He was suffering an epileptic seizure and she has come to take him to the doctor. A well-dressed woman who left work in her SUV, she talks to me about her son’s disability. I feel a deep sympathy, accompanied by shock that I have not experienced such feelings with any other parent. She is like me, in ways the other parents I have met are not. And now I can see that my own social-intellectual class is affecting my classing of them.

The unfamiliarity of the ways of living and thinking in these classrooms is surprising and invigorating. Places of differently classed bodies are also places of different practices of classifying. This is especially the case in the most differently socially situated of classrooms, that of this Special School. What its teachers, Diane and Michaela, practise with great skill is not delivering planned lessons but responding appropriately to the rapidly shifting needs of students. They are enacting the feminist vision of the knower who does not look and think from afar, but is flexible, responsive, and responsible. They are doing a relational metaphysics. My habit of forming classes about the ‘real’ via mental reflection are challenged by their practices. Their classification of good knowing gels with what I intellectually agree with, but have never formally learnt to practise.

The challenge I face in appropriately analysing these practices of classifying that are so radically different from my own is one of ethics. The question is how to use my classed and classing body in ways that will give due credit to such differently classed and classing bodies. This is the problem of double participation.

Double Participation

Before the kids are allowed into the bag room to collect their lunch, Diane goes in to check it’s clean. Standing by the door, she announces, ‘There’s no food on the floor there now, and there won’t be any after lunch either, will there? Sometimes,’ she continues, ‘food mysteriously appears there on the floor, but I’m sure it won’t today’. Dwayne suggests, excited, that maybe there is a ghost, but Diane says, clear and firm, ‘No. There is no ghost’. The kids get seated with their sandwiches, and Diane turns to me. ‘You’ll go back to your university and say “Geez! They were the stupidest people I ever spent a day with”’. (Author field notes, Special School, 8 October 2007).

Diane is pointing out to me the double-ness of my participation. I am here in this classroom, watching and joining in with what happens. But, she is suggesting, I don’t really fit here. I will return to university and say ‘geez, how stupid they were’ to the people I really belong with, roll my eyes and criticise, or mock those I have been researching.

Though, in fact, I was always impressed by what I saw at Special School, Diane’s prediction mapped a general problem in the ethics of fieldwork. Kathryn Addelson refers to this problem as ‘double participation’. Describing the research done by Prudence Rains towards writing her 1971 book Becoming an Unwed Mother: A Sociological Account, Addelson points out that Rains was part of two types of collective action. She was part of the ‘ongoing personal and everyday collective lives of the subjects’. Simultaneously ‘there was the collective activity that she took part in as a professional researcher, activity that constituted her discipline and the institutions of science’. (Addelson 1994: 160). Her participation was double because she was acting in and for two separate groups – unwed mothers and sociologists. She was engaged in ‘double participation’.

What Diane was pointing out was that I too was engaged in ‘double participation’ between her classroom and my university. This was partly a matter of differently classed bodies. In her version I would return from this low-income city margin to my university in the CBD. There I would sit with friends and colleagues rich in cultural, if not financial capital, and find ways to act – to speak and write – with them. She was reminding me that my body was not embedded in the same hierarchies of wealth, knowledge, or status as those bodies I was acting with in her classroom.

Further, she was suggesting that I would classify what I was experiencing in terms my university colleagues would already agree with: that the collective action at a school for low-IQ students was itself stupid. My classed body, she was saying, opened onto a classing body. Again her prediction was insightful. Universities are sites rich in rules for how to classify information. My classifying habits are built by participation in university knowledge practices, particularly those of the disciplines I have specialised in. Each discipline has rules that guide how to chunk up the world into segments. These rules are shared (to some extent) across a university system, constituting standards – a ‘set of agreed-upon rules for the production of (textual and material) objects’ (Bowker and Star 1999: 13). These provide cognitive authority, placing us, ‘in the local sites of laboratory and field [and classroom], not as participants but as “judging observers” who are themselves to be unjudged’ (Addelson 1994: 161). Only by showing myself capable of certain classing actions could I have attained my position as PhD student. Over years of writing essays and sitting exams, I had passed through gates kept closed except to those who could write in ways that showed an ability to put ideas in groups in a particular way. And it was by being a PhD student that I had gained the ethics clearances and agreements from principals necessary to being allowed here. From success in approved systems of classifying comes access to sites for classifying.

Diane’s classroom did not work on skills of thoughtful and rational classification like those practised in universities, but on quick, flexible responses to flows of action. These were ways of acting that I found myself unused to, feeling bodily and mentally clumsy much of the time. In contrast to those of Diane and her fellow teachers, my skills at classifying were unsuited to this classroom context. A test came one day when Diane was away and we had a relief teacher new to this type of school. Before lunch he sat and read from a book of fables the class was already familiar with. This should have been easy; Michaela, the teacher aide, assured us that the class loved this book. He read the first story right through, including the closing moral. ‘Any questions?’ he asked. A couple of kids described parts of the story. He turned to the next story. I could see that his lesson was not working, and I thought that his problem was that he was not helping the children build groups of situations when these morals might apply. I believed I could solve his problem by pushing children into making classes of situations that fit the moral of the stories. When the teacher had read the next story right through to the end (‘don’t throw stones if you live in a glass house’), I suggested we come up with other examples of things that happen at this school to illustrate the moral. I described one: ‘if I yelled at everyone else to stop yelling’. The kids responded, but by talking about how you lose a star if you yell. They did not follow me in classifying their lives in terms of these morals, and instead followed a classifying pattern that places actions mentioned in terms of school rules. Both relief teacher and I had failed to form these stories into shapes that the class could respond to in meaningful ways. What this means is that we had failed to reproduce Diane’s ways of guiding children’s classifications or to create new ones the children would engage with. With Diane they love this book; with us they do not understand.

Recognising that different ways of classifying information are necessary to be a successful part of the action that occurs in Diane’s classroom provoked an ethical challenge. It is a challenge I faced not only in the classroom, for through participation there I worked at and gradually improved my skills at responding to children in ways that seemed to work. The bigger ethical challenge came from returning to an academic institution and seeking to describe and explain just why the collective action I had witnessed in Diane’s classroom had been so impressive. How to explain the broad value of a way of acting with lowly classed and poorly classifying bodies, to people of high status sourced from their ability to classify in wholly different ways? How to do justice to the talent of Diane and Michaela, two highly skilled professionals from the margins of their profession? This is a question of how to suitably express the value of a relational metaphysics to a group generally attached to a foundational metaphysics. My solution has been to make these two logics explicit and to be reflexive about my attempts to follow that of relations. My reflexivity is intended to relate my classed and classing body to how I am able to understand classrooms.

Conclusion

I have explored here two modes of ordering that tell us something of what classrooms are. In the first, a mode of ordering based on the relations between school and society, we were able to think about educational traditions and goals for individual and social futures. We saw schools presenting themselves as environments for the production of people suited to (making) ideal societies. Here we also saw the participant-observation researcher as having the ethical duty to represent these classrooms in terms of the school’s meanings and values.

In the second mode we explored the classroom as an assemblage of classed and classing bodies. Here was the double-ness of being materially and socially positioned and expected to classify in particular ways: to be classed and classing. This seems to me to be both a more useful and a more ethical account. These experiences in classrooms forced my classed and classifying body into acting with the very different classed and classifying bodies of others.

For your author, knowing comes through participation in and for two collectivities (classroom and university) both of different classes and with different modes of classifying. This could be emotionally and psychologically difficult. I was occupying a ‘borderland’: Bowker and Star’s term for the situation of having ‘two communities of practice co-exist[ing] in one person’ (Bowker and Star 1999: 304). This, I would suggest, is always part of doing participant-observation in some way or another and it is a rich place from which to generate understanding. It impacts on how we are able to represent classrooms in writing, for being a classed and classing body myself I cannot simply tell ‘how it was’. What I tell instead is how I was able to understand by following out the knotted strings of ‘class’.