11

Social Media as Experiments in Sociality

Noortje Marres, Carolin Gerlitz

Introduction

What does the ‘social’ in social media refer to? This question has been much debated in recent years, and the range of answers provided is impressively wide (Coleman 2013; Van Dijck 2013; Davies 2015). Some argue that today’s social media are not that special, as media technologies have always been social: older incarnations like the telephone and the radio equally depended on their uptake in social life for their functioning and success, and earlier internet applications like email and online discussion forums facilitated many of the forms of social connection and exchange that are today associated with popular online platforms dubbed ‘social media’ (Coleman 2013; Papacharissi 2015). Others have countered that we shouldn’t just go along with the designation of online platforms as ‘social media’, as this is to confer legitimacy, or ‘street cred’, onto them: we should in fact criticise this very label. Thus, Couldry and Van Dijck (2015) argue that the ‘social’ in social media lacks a referent: in their view, and contrary to popular opinion, online platforms are not social but anti-social, as their mode of operation goes against many long-held norms and values regulating social life, such as the ideal that sociality should serve no other end than itself. In sharp contrast to this, many platforms frame sociality as an instrumental activity that serves other objectives such as gaining influence or attention, or of generating metrics and data. Finally, according to yet others, we should not so readily dismiss the possibility that a special relationship exists between the digital technologies known as social media and sociality. For one, popular platforms such as Facebook and Twitter are remarkably well-aligned with sociological understandings of social life, such as the idea that people form ‘social networks’ or ‘perform’ the self in everyday life (Thielmann 2011; Hogan 2010; Healy 2015).

In this chapter, we seek to contribute to this debate about social media technologies by offering a fourth, different answer to the question of what makes social media social. On online platforms, we propose, sociality becomes the subject of experimentation. An outstanding feature of social media is that they not only facilitate existing social activities, practices, and relations, but also encourage the creation of new ones, allowing for what some have called the ‘enhancement’, ‘augmentation’ or ‘elaboration’ of sociality (Healy 2015; Bucher 2013). In this article, we want to make the case that this has important consequences for our wider understanding of the relations between media technologies and sociality in our age. Specifically, it follows from the above that we should not treat mediated sociality as a given attribute of existing media technological infrastructures, arrangements, and practices. Instead, we must treat the sociality of social media as an experimental accomplishment: whether or not sociality is successfully realised with these technologies depends on how digital infrastructures, devices, and practices are configured, more or less deliberately so. We should, then, not only be debating whether social media are social or not – whether in and of themselves these technologies support social connections, expression, exchange, reproduction, and so on. We should equally examine how the accomplishment of different forms of sociality depends – in a non-straightforward way – on how digital infrastructures, devices, and practices are assembled in practice, and the contributions that social researchers themselves can make to this.

In this chapter, we explore such an experimental take on the sociality of social media platforms in two ways: first, we situate the debate about digital sociality in the context of recent debates in social theory about the status of ‘the social’ in contemporary societies. We propose that the online platforms popularly known as ‘social media’ re-open a debate that many thought was closed, namely that about the relations between the social and the technical. Second, we discuss a collaborative project in social media analysis which we developed together with Esther Weltevrede and others during the Digital Methods Summer School in Amsterdam in 2013, and in which we sought to develop an experimental understanding of sociality with social media technologies. This project found its starting point in a remark by the British sociologist Emma Uprichard, who during a pointed exchange in the summer of 2012 insisted, ‘Just because it is called social, doesn’t make it social!’ (see also Marres 2017). Adopting this dictum, our project took up the tools of Twitter analysis to develop a range of experimental answers to the question ‘what is social about social media?’ Finally, we draw on this pilot study to argue that digital platforms enable a distinct type of of ‘arte-factual’ sociality, one that invites or even requires the development of new, experimental research strategies for understanding social life with social media.

What Social Media Can Tell Us About ‘The Social’: It’s Back but it Hasn’t Returned

Arguably, social media can be considered part of a bigger family of what social theorists have come to refer to ‘the new socials’. Mike Savage (2009: 171)1 has noted that digital arrangements affect the everyday organisation of society as an object of knowledge, as ‘ordinary transactions, from websites, Tesco loyalty cards, CCTV cameras in your local shopping centre etc., are the stuff of the new social’. Will Davies (2015) has commented on the proliferation in the last decade of neologisms such as social enterprise, social technology, social design, social marketing, social innovation, social analytics, social bonds, social journalism, and so on. These ‘socials’ can be called ‘new’ insofar as these arrangements and labels can be contrasted with ‘old socials’ associated with an earlier era of progressive investment in the planned society, such as social policy, social housing, and perhaps indeed, social research. Thus, while many of the ‘old socials’ are connected with the welfare state, the new socials signal efforts to bring economy, culture, and politics together under a regime of innovation that no longer depends on centralist planning. The advancement of new socials, furthermore, often involves efforts to bring technology and society into closer relation, where the former is no longer considered antithetical to the human bond, but somehow generative of community, togetherness, and related values – a capacity especially ascribed to digital technologies. It has for instance been argued that what makes the digital economy different from other economies is its relation to ‘the social’: Will Hutton opposed the social entrepreneurship of Palo Alto to the ‘anti-social’ economy of austerity Britain (Marres 2017).2 We can even observe a recent tendency to claim that the digital has the capacities to make any sector, arrangement or practice ‘more social’: social media technologies allegedly enable companies to be more engaged, responsive, in touch, aware, and so on. However, this introduction of digital devices into social practices remains a largely instrumental operation, mainly serving the aim of understanding audiences (through monitoring), cultivating markets (social branding), and/or extracting data and value. As such, the new ‘socials’ mostly do not refer to anything that sociologists call by that name, but rather invoke conceptions of sociality that have been prevalent in marketing, audience research, and strategy where informal exchange and mundane interaction have long been recognised as a valuable conduit for the cultivation of brands and markets (Moor and Lury 2011).

However, this is not all there is to recent invocations of the social. To begin with, it is not the case that labelling online platforms as ‘social’ operates on the level of ‘sloganeering’ or ‘labelling’ only. Many online platforms also implement versions of sociological theory and methods (Bucher 2013; Healy 2015). Take ‘People You May Know’, the algorithm developed by the professional networking site LinkedIn and subsequently implemented by Facebook, where it is used to suggest users to connect with (to ‘friend’). As LinkedIn itself proclaims on the company blog, this algorithm implements a concept developed by the sociologist Georg Simmel, namely his principle of triadic closure, the phenomenon that if one person knows two people, these people are likely to know each other.3 As such, it could be argued that social media enable the ‘materialisation’ of sociological methods and concepts across organisations and social life, as their uptake across settings results in the partial reformatting – and perhaps to an extent also the re-organisation – of social life as analysable phenomena: as social networks, social trends, and so on. Partly for this reason, we think it would be a mistake to assume too strict an opposition between ‘the new socials’ advanced with the aid of digital technologies and ‘the social’ as conceived in social theory and social research.

Furthermore, the uptake of social concepts in contemporary technological, creative and organisational contexts can be understood as posing a wider challenge to debates in social theory about the fate of ‘the social’ in technological and knowledge-intensive societies. From the 1980s onwards, social theorists announced ‘the end of the social’: in this period, Bruno Latour (1993), Nikolas Rose (1996), Karin-Knorr Cetina (1994) and Jean Baudrillard (1988) developed different versions of the claim that we were moving beyond ‘society’ and entering a post-social epoch. While their interpretations of this general idea differ, each of them argued that the ideal conception of society as a homogeneous whole directed from a position outside it was losing plausibility in our time, either because of the demise of the ideal of a socially engineered society and the welfare state (Rose 1996), or more positively, because of the emergence of a different ethical and political proposition for the organisation of society, such as that of heterogeneous collectives (Latour 2005), in which not just humans but also non-humans participate. This latter approach presented society and post-society – or rather non-society – as mutually exclusive: either we continue to adhere to classic understandings of human society, or we affirm the existence of heterogeneous collectives, and being for society meant being against the recognition of non-humans as participants in social life.

Seen against this backdrop, digital media present social theory with a usefully heretical proposition: they combine both positions – society and heterogeneity – in remarkably successful and unsettling ways. In the case of online platforms, it is perfectly possible to specify a given formation as both heterogeneous in composition and social in form and orientation. These platforms present us with a Janus face: they constitute a socio-technically heterogeneous phenomenon made up of technical and social entities and they enable the organisation and analysis of classic social formations such as community and society (Marres 2017). How to account for these Janus-faced, heterogeneous socials?4 It is important to recognise that the approximation between sociological methods and concepts and technological infrastructures that is so clearly observable in the case of social media technology, is not ‘new’ as such. Sociologists have long drawn attention to this very phenomenon in discussions of historical devices, infrastructures, and practices of social organisation and knowledge: in particular, social research instruments such as the survey, the opinion poll, and the focus group have been characterised in terms of their double function as serving both as a tool for the analysis of societies and as an instrument for intervention in public, economic, and social life (Didier 2009; Osborne and Rose 1999; Lezaun 2007; Law and Ruppert 2013). As such, social media reactivate sociological debates about the necessarily reflexive quality of social life and social research, as theorised for example by Anthony Giddens (1987) in his work on the double hermeneutics that make ideas circulate between sociology and social life, and by Aaron Cicourel (1964), who famously argued that social methods are only applicable to social life by virtue of the uptake of the categories built into these methods across social life. Social media platforms invite us to explore these ideas anew, but we propose that they also disrupt some assumptions associated with concepts of the ‘reflexivity’ of social life and social analysis.

To see this, there is a further point that requires attention: social media technologies highlight the ‘arte-factual’ quality of digitally mediated sociality. The social activities, practices, and relations enabled and made visible by social media are not necessarily representative of society at large, partly because they are informed by media technologies themselves. Both expert and popular debates increasingly recognise that social media are biased towards certain forms and types of sociality (Gerlitz and Helmond 2013). One way in which this bias became clear is when we visualised students’ Facebook networks in a classroom setting: these networks often told us much more about how Facebook works (‘the platform encourages the accumulation of friends’) and about Facebook-specific behaviours (‘he is a very active Facebooker’) than about people’s social relations. Social media platforms are designed for ‘social enhancement’, and the sociality they enable and make visible often does not exist before or outside the platform. Sociality enabled by social media, then, resists naturalization: it is demonstrably an arte-factual accomplishment. We find this is among the most interesting and important provocations of social media to our understandings of sociality, one that has the potential to translate into a wider ‘experimentalisation’ of the social, which would mean that the forms of sociality enabled by these and related socio-technical infrastructures are not given but ‘curatable’ and potentially open to reinvention.

To better understand this potential (re-)qualification of the social in digital media environments, we need to take a step back and consider whether and how this idea of ‘experimental’ sociality relates to another, better-known concept, that of the ‘performance’ of social life, which has been used by social theorists to demonstrate that social life is not a natural or given phenomenon but staged, produced, and realised deliberatively and effortfully (see the introduction to this volume). A performative account of society suggests that there is no such thing as an ‘independently existing’ social order, and sociality must instead be understood as – to use Harold Garfinkel’s terminology – an ongoing accomplishment. Social media have granted empirical plausibility to this understanding of performed sociality, as they are designed to enable both distinct (and often economically valuable) performances of the ‘self’ through profile pictures, tag lines, walls, and so on, as well as the performative demonstration of social formations such as social networks and collective dynamics, with the aid of network maps and trend lists (Ruppert, Law and Savage 2013). Drawing on Harold Garfinkel’s ethnomethodolgy, the German media scholar Tristan Thielmann (2011) has pointed out that online platforms enable everyday actors to produce ‘accounts of social life as part of social life’. Platforms from Facebook to Instagram prompt users to generate reports of mundane occurrences (Where did you have dinner? With whom?). As such, social media appear to realise Garfinkel’s ethnomethodological idea that social life ‘accounts for itself’: they enable the proliferation of accounting devices that render mundane moments and informal interaction recordable, analysable, and curatable for practical purposes – and this by way of data formats defined and made available by the media themselves, such as like shares, status updates, friend requests, and so on.

However, in other ways, today’s social media platforms also precisely go against this kind of sociological understanding of social life as an object of knowledge. For Garfinkel, highlighting the performative quality of social life was a way of dismantling the status of sociology as an independent discipline. If social life can account for itself, this would make the development of distinct methods for sociological inquiry obsolete. But today the intensification of the accountability of social life is accompanied by loud reassertions of ‘the social’ as a distinctive form of organisation, and of the need for a new ‘science of society’. The head of the Facebook data science team not so long ago referred to himself as a ‘digital sociologist’ (Simonite 2012). Social media, then, present sociology with a paradox: the infrastructures, devices, and practices that are associated with ‘the new socials’ equally exhibit features that sociologists associate with the ‘end’ of the social. Another way of putting this is to say that, from a sociological perspective, social media platforms appear to be methodologically and conceptually promiscuous: they exemplify insights from performative sociology but equally support a realist science of society. Indeed, is it not partly because social media platforms come with various in-built ‘performative’ devices that elicit the ‘accounting for social life as part of social life’, that they enable the proliferation of rather ‘conventional’ sociological measures and methods?

The easiest, most feasible way of conducting social research with social media is to take up popular free online data tools which facilitate things such as the analysis of personal (human-to-human) networks, or the measurement of reputation and influence – all forms of sociological analysis that have been part of the sociological repertoire since at least the post-war period. In some ways, social media radicalise these forms of analysis. One could say that ethnomethodologists held on to a certain idea of social life as given, insofar as that ‘performative’ quality of social life was for them an un-changing attribute, an ontological truth. Also, while the performative sociology of the 1960s had assumed that the formats for accounting ‘for everyday life as part of everyday life’ were mostly readily available in and as social life, today these formats have become the object of rather intense efforts to design, innovate, and domesticate ‘new’ devices of social accounting.

The work of information theorist Philip Agre (1994) is relevant here: in his studies of employee management, Agre proposed the notion of ‘grammars of action’. This notion recognises that the production of ‘accounts for social life as part of social life’ involves instruments and the configuration of infrastructures, whilst also attending to the design efforts involved. Employers devise these grammars as predefined sets of actions – such as conversation scripts in call centres or step-by-step guidelines for dealing with customer complaints – that immediately enable their own datafication, rendering them recordable and analysable. The distinction between actions and their capture collapses in the process of grammatisation, and both are subject to intensive design, standardisation and formatting. In the context of social media platforms, pre-structured platform activities such as liking, tweeting or replying can be considered as examples of such grammars, which are offered by platforms and realised by users. However, these grammars can only standardise the form of action and data, not its interpretation by users and other stakeholders, who, to a certain degree, can inscribe their own practices and meaning into the grammars provided, taking advantage of interpretative flexibility (Pinch and Bijker 1984; Paßmann and Gerlitz 2014).

As such, social media, and possibly other new socials too, do not quite comply with a performative understanding of social life. They present us with a further ‘experimentalisation’ of the social: it is today not self-evident what forms of sociality, what theory of society or of social life, will be realised as a consequence of the proliferation of devices for ‘accounting for social life as part of social life’. There are myriads of possibilities: for example, will the paradigm of incentivising and nudging by way of social media buttons translate into the invention of a behavioural society, one constituted of more or less atomistic individuals defined by their actions? Or will organic forms of society be reinvented in the sense of a return to the imagination of a collective body that transcends the individuals that make it up? While theorists of the ‘end of the social’ in the 1980s and 90s considered this debate more or less closed (in favour of the former), we consider it reopened: ‘the social is back’ as an issue to be grappled with. And this return does not necessarily present a return to the familiar: today’s situation signals a possible experimentalisation of the social. We face a paradoxical situation, one in which sociality figures as an intense object of design, engineering, and analysis, while the theories of sociality that are deployed towards this end tend to conceptualise society in terms of a human population or community. The rise to prominence of ‘social media’ correlates with increased levels of ‘artifice’ involved in the making of sociality, but at the same time the claim that social data enable an ‘unfiltered’ understanding of a given society is widely endorsed. It is in order to hold on to these paradoxes that we insist that today we are facing a ‘not quite’ return of the social. And it is this ‘not quite’ that we seek to specify, by approaching social media as a site for the ‘(re)invention of sociality’.

Methodology: How to Study New Socials with Social Media

We are struck, then, by the odd confluence of ideas, devices, and imaginaries of sociality in social media, at least some of which seem mutually incompatible or in tension with one another. This situation can be investigated by different means: it can be engaged theoretically, for example by tracing genealogies of the concept of the social (Halewood 2014), or it can be analysed empirically, through case studies of particular social media technologies, such as buttons or flags, to specify their role in the performance of mediated sociality (Helmond and Gerlitz 2013; Crawford and Gillespie 2014). But in what follows we adopt not so much an empirical but an experimental approach: we do not just ask what definitions of sociality are being advanced through social media, which would be a way of delegating the definition of sociality to our empirical object. We also do not attempt to locate sociality in the technical features of social media platforms and the possibilities they offer for interaction and connectivity (Boyd and Ellison 2007), in the content created by users (which invites spreading) (Langlois 2014), in the context of use (Slater 2002) or in the data they render available, such as social network connections (Gerlitz and Rieder 2017). Instead we would like to engage with social ontology as something that is collectively accomplished in social media environments, and approach this accomplishment as something in which we – as social media researchers and theorists – actively participate.

We thus approach the social as a ‘happening’, to take up the concept offered by Nina Wakeford and Celia Lury (2012): a distributed accomplishment of users, technicity, data, practices, methods, measures, and other yet to be determined elements, of which the collective effect is fundamentally uncertain. We then approach the question of ‘what’s social in social media?’ in an open-ended way: rather than conceptualise the productive capacities of methods and devices in terms of enactment, we think of them in terms of participation. In doing so, we also take our cue from Michel Callon (2006), who insists that empirical sociology must be willing to derive its classifications from the case at hand. In his discussion of how to analyse large numbers, Callon suggests that ‘[o]ne way of testing the relevance and robustness of a proposed categorization is to allow the entities studied to participate in the enterprise of classification’ (2006: 8). In our view, such attention to actor-defined categories is significantly complicated in digital research, as it is not just the actors (that is, the users, the platforms, or associated developers), but also contexts of interpretation, tools for data analysis and their settings, the issue at hand, visualisation strategies, and so on, that play a role in establishing the (ir)relevance of particular classifications and assumptions over others. The task of experimental social inquiry is to formulate research strategies that render such participation methodologically viable.

To give some concrete examples of this experimental strategy in social inquiry, we will discuss a group project that we initiated during the Digital Methods Summer School 2013 to address the question of ‘what makes social media social?’5. The Digital Methods Summer School is an annual postgraduate event, initiated by Richard Rogers and hosted by the University of Amsterdam, which introduces students and scholars to digital media research through participation in collaborative research projects. Small-scale projects are designed, realised and presented within a week. The aim of our project was to use digital methods for practice-based social research (Rogers 2013). For this particular edition of the summer school, we collaborated with Esther Weltevrede to pitch a project called ‘Detecting the Social’, and developed it together with around twenty scholars, designers, programmers, and activists, bringing together expertise in media studies, sociology, computing, design, and science and technology studies (STS). In what follows we will narrate selected findings of this project in order to illustrate the range of ‘socials’ that we found to be ‘in play’ in social media, and to discuss what an experimental approach to new socials might look like.

Starting with the idea of the ‘happening’ of the social (Lury and Wakeford 2012), we abstained from preconceived accounts of sociality and explicitly recognised the heterogeneity of social concepts, methods, and forms that are designed and practised in digital media environments, and the participation of our methodological apparatus in them. To structure the project, we divided our group into three sub-groups, each of which was tasked to explore a different ‘way into’ the social: interaction (Gerlitz), the non-human (bots) (Weltevrede), and content (Marres). Our aim was to produce an overview or ‘mapping’ of different happenings of sociality that are ‘detectable with social media’ (see for a similar approach, Kelty et al. 2012). In line with the prevalent approach adopted by the Digital Methods Summer School (Rogers 2013), we limited ourselves to using methods of online data analysis and visualisation, and focused on one platform only, namely Twitter. It is important to note that relying on platform data in this way offers a highly partial view, one which does not account for user interpretations and practices, or socio-material and organisational features of social media infrastructures. However, this narrow focus seemed to us well attuned to our wider methodological project of studying the ‘happening’ of the social: we could account for the sociality enacted in and with Twitter ‘from the inside’, and examine a range of forms of sociality with the same data set: user interactions, content dynamics, and the composition of collectives (humans and non-humans).

Twitter was chosen as a site of experimentation as the platform is known for the relative ease of data access, the diverse character of at least some of its content, and its explicit yet limited grammars of action and interaction (tweets, @mentions, retweets, user accounts, hashtags, and so forth). To account for media and content dynamics, we settled on a topical dataset containing tweets relating to the topic of ‘privacy’, as captured with the Digital Methods Twitter Analysis and Capture Tool (TCAT) (Borra and Rieder 2014). These tweets were posted between 23 May 2013 and 15 June 2013.6 During this period, the news of Edward Snowden’s data leak broke, an event which operated across a variety of registers, including journalistic, activist, tongue-in-cheek, and geo-political. This broad scope of the event seemed helpful for our project of capturing different modalities of interaction and collective expression on Twitter.

Each of the three groups examined the sociality of Twitter from a distinct angle, namely interaction, non-human activity, and content or hashtag dynamics, and issue composition. We were aware that by choosing this approach we aligned ourselves in various ways with dominant measures built into Twitter and Twitter analysis. The platform is famously biased towards particular forms of sociality, such as popularity (trends), celebrity (star users) or viral dynamics (memes). However, our own preoccupations – with interaction, non-humans and issue formation – in this project have a clear sociological signature, as each is associated with more or less established sociological approaches such as interactionism, Actor-Network Theory (which has introduced the concept of the non-human), and issue mapping (Marres and Rogers 2005). Our commitment to ‘detect’ sociality certainly does not imply that we adopted a ‘blank’ attitude (Mackenzie 2012): we did not only invite the medium to tell us what makes it social, but rather attempted to deploy social research methodology in order to detect happenings of sociality that do not derive from platform features.

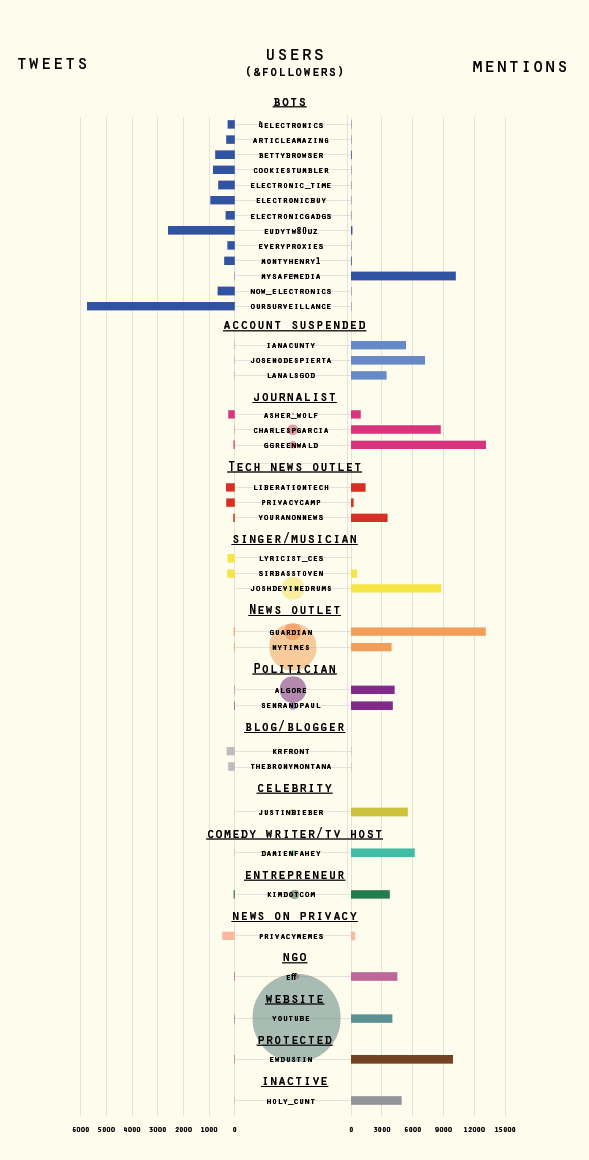

Social 1: User Interactions

To get at forms of sociality enacted with Twitter, the first group focused on features or grammars that Twitter makes available for users to interact with other users, namely tweets, @replies, retweets, and interaction chains. In doing so, this group sought to attune its method to the medium by exploring how Twitter features are instantiated in Twitter use, with a focus on detecting interactional patterns in the data. Aware of Twitter’s own focus on the most popular or frequently occurring (top trends, popular users), we started by identifying peaks of activity and interactivity. Starting from the pragmatic assumption that the more active a user is, the more likely the disclosure of interactive patterns, we identified the twenty most active and interactive users. The group manually categorised these top users, generating a range of user categories (journalists, celebrities, and so on) in the process: Figure 11.1 shows the resulting categories, with number of tweets on the left and received mentions on the right.

As a first pattern, we noted the wide gap between those users who are most active and those who are referred to most. Accounts with many mentions mainly included journalists, media and news outlets, celebrities, politicians, and (unavoidably) pop singers – that is, accounts that thrive on existing media exposure and popularity beyond Twitter. Among the most active users on the other hand, we mainly found automated accounts – which we categorised as bots, although we later came to problematise this category. Bot activity includes software-supported automated tweet production, or cross-syndication of content from other media sources. These bots receive few mentions, but output comparably high volumes of tweets. We speculated that the category of the individual user may not necessarily map well onto that of a social media account, as many of these accounts cannot be linked to a single agentive individual, but rather express potentially distributed professional activities (news outlets or celebrities may employ social media agents) and varying degrees of software-supported tweeting. These findings further elicited discussions about the usefulness of frequency-based measures for detecting the social, as those who speak most loudly on Twitter are not spoken back to, and vice versa. It appeared that focusing on the top frequency layer of social media data, at least in this case, means to value currency and liveness more than interaction, leading to a highly partial view.

Fig. 11.1 Top twenty most active users based on tweets and mentions (created by Stefania Guerra)

Our initial exploration of the data produced, then, in Callon’s (2006) expression, a moment of objection, in which our findings confronted us with the limits of our own measures and assumptions. We therefore decided to change our focus to users that are both active and mentioned, most of which can be found in a mid-level frequency tier of users who tweeted between 100 and 300 times, and who achieved at least twenty mentions. Focusing on the 120 most inter/active users, we again manually categorised their accounts and compared their tweets and mentions (Fig. 11.2). The majority of these interactive users, we found, were activists and issue-focused journalists, engaging in mutual interactions. The exercise showed us that whilst it is tempting to focus on top-tier frequencies to ‘sum up’ a data set, its highly partial perspective exemplifies the importance of adjusting our measures to our data, in light of our question.

Fig. 11.2 Interactive users (fragment of a visualisation created by Gabriele Colombo)

In the last leg of Group 1’s work, we moved from users to patterns of inter/activity. We traced reply-chains, that is tweets followed by at least one or more replies (Fig. 11.3), and found that the majority of chains only consist of two elements – that is, a tweet by user A and a response by user B (not followed by another response by user A), rather than taking the more lively form of mutual tweets and replies. This finding seems in line with the discrepancy between active and mentioned users noted above, as the majority of users that are being replied to do not reply back. Overall, we found three types of interaction prevalent in our dataset: (1) the chain, in which one tweet is followed by a number of mutual replies, (2) the star, in which a user receives multiple replies to their tweet but does not respond back (the most prominent formation in our data set), and (3) other forms that mix star and chain elements, in which some replies are answered. Chain-like conversations can mainly be found among users who have similar follower numbers. Within star constellations, the respondents mostly have significantly fewer followers than the originator. This indicated to us that mention activity does not necessarily point to interactivity.

To sum up, the work of Group 1 demonstrated to us the well-known methodological point that methods and measures participate in the specification of the phenomenon under study: by taking up tools of social media analysis, attention is initially drawn to dynamics favoured by the device (Twitter), such as celebrity and popularity, at the expense of interaction. However, in engaging proactively with this point during data exploration, we also moved beyond this observation: we adjusted our focus in order to bring into view dynamics that are less prominent but no less relevant. The notion of the performativity of social methods is rather asymmetrical, as it attributes the capacity to structure the phenomenon it is supposed to render observable to the device. By contrast, the procedure of the mutual adjustment of data, methods, and concepts we followed in our experiment allowed for a more symmetrical form of ‘participation’: our methodological operations allowed Twitter data to participate in the production of accounts of social interaction online, rather than focus solely on the demonstration of ‘device effects’ (Gerlitz and Lury 2014). Indeed, we actively sought to reduce specific reactive effects7 that contribute to the enactment of some forms of sociality over others on Twitter.

Social 2: ‘Automated’ Sociality

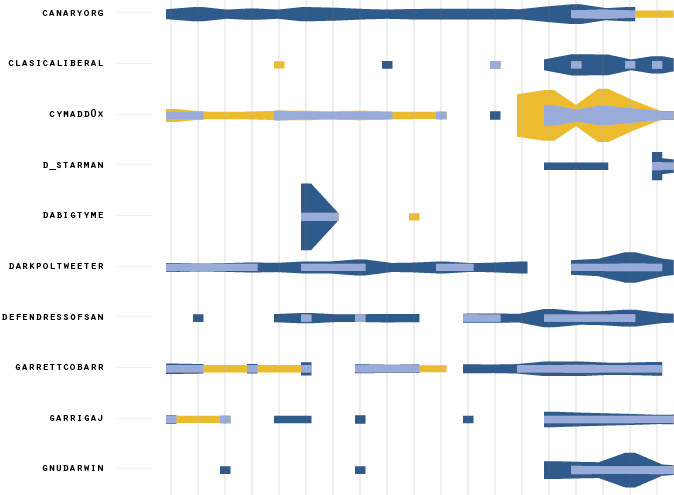

Our exploration of Twitter interaction above has already highlighted that humans can only account for part of this activity. In the context of social media, other-than-human activity is often labelled ‘bot activity’, as it involves the use of predefined, automated scripts of different sorts (Wilkie et al. 2014; Niederer and van Dijck 2010). Bots tend to be associated with spammy, promotional, and malicious behaviour, and as such they have been understood as threats to online sociality, undermining the general quality of online interaction and the quality of data (Hargittai and Sandvig 2015). However, Group 2 was not so much interested in taking a normative position towards the role of bots, but rather wanted to see whether and how ‘bot activity’ online was analysable in social terms (Jones 2015). After all, there is a significant legacy of non-social methods for identifying bots, of which the mentalist method of the Turing Test is the best known. This group, then, was interested in taking the term ‘social bot’ literally, to develop an account of the role of technological agents in social media environments that did not so much rely on mentalistic conceptions of what a bot is (‘artificial intelligence’), or normative assumptions about whether it is good or bad, but rather considered the habits and practices of automated accounts. To do this, Group 2 began by dropping the term bot and taking up the idea that online sociality is automated to varying degrees. We favour the term automatisation over the discrete notion of bots, as the former allows for a more nuanced and inclusive conception of more-than-human activities online.

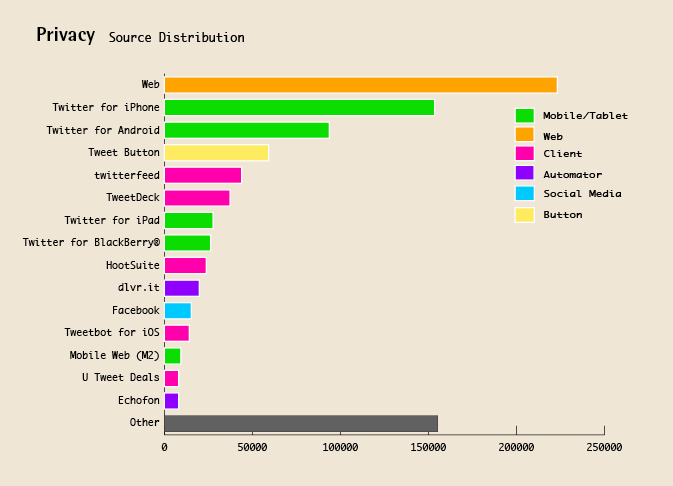

Research by Gerlitz and Rieder (2017) has noted the growing and varying degrees of software-assisted tweeting. Analysing a random Twitter sample, the authors identified the range of sources from which users tweet, each of which support different degrees of automatisation, such as button-supported tweets, cross-syndication of content from other platforms, in-app or in-game tweets, scheduled tweets, automated retweets based on keywords, hashtag or user mentions, fully automated accounts, account networks and retweet cartels. Mobile devices and clients are found to be taking over the Twitter web client as the main access point to Twitter, and this proliferation of sources and their features asks for a more fine-grained notion of automatisation. Rather than viewing the couple ‘human and non-human’ as a binary, then, we approach it as a continuum or spectrum based on activity patterns.

As a first step, Group 2 identified the sources from which users tweet.8 In our dataset, tweets were sent from 4267 different devices and sources; Figure 11.3 shows the top fifteen. Twitter for Web, iPhone, and Android are among the most used, followed by a set of sources which support different degrees of automatisation. Tweet Buttons make it possible to send web content directly to Twitter. Twitterfeed, Tweetdeck, and Hootsuite are clients that allow users to access, organise, and post to Twitter, offering extended analytics on reach, engagement, interaction, and scheduled tweets.9 Importantly, the majority of tweets are produced outside the interfaces provided by Twitter itself, which suggests that the ‘degree of automation’ is subject to a multi-faceted information ecology, of which Twitter is likely to form only one part.

Fig. 11.3 Devices used to send tweets (created by Allessandro Brunetti)

The question is whether and how we can characterise this spectrum of differently automated accounts in social terms. To address this question, we explored the possibility of categorising automated accounts in terms of activity patterns. This proved relatively straightforward, as many automated accounts were remarkably mono-manic in their social media habits – they tend to send a disproportionately high number of tweets featuring specific selections of contents or hashtags. We reached this conclusion by tracing which hashtags are being used in tweets sent by specific sources. In the context of our privacy dataset, we discovered at least two orchestrated high-frequency promotional efforts. First, tweets sent from ‘U tweet deals’ mainly appear with the hashtags #home and #surveillance, and send users to ebay.com. Second, tweets using a combination of hashtags (#free, #blog, #photos, #websites, #videos, #mp3, #videochat and #emailblas) were linked to Mysavemedia.com. Interestingly, these tweets were not sent by a tweet automator, but via the Twitter web interface. Digging deeper, we found that most Twitter widgets, including Twitter buttons, are routed via the Twitter web interface and thus also appear in the dataset as sent from Twitter web. So even sources that seemingly point to manual practices have to be treated with care and can be the result of automatisation. In both instances, automated activity takes advantage of the relative popularity of the topic (privacy) to create and broadcast to an audience as a promotional effort. Faced with this, we sought to discover whether we could plot automated Twitter activity along a spectrum that goes from broadcasting to more interactive forms of publicity. Are some bots more social than others?

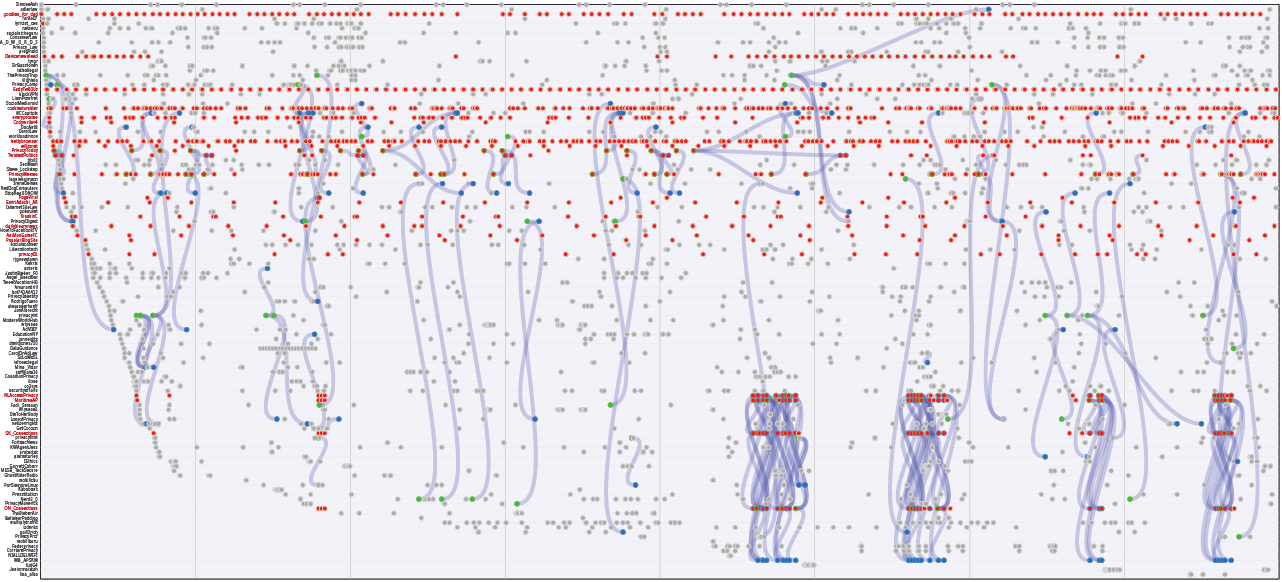

To explore this, we produced a cascade visualisation (Fig. 11.4), which lists users on the y axis and plots their activity along the x axis, where each tweet marks a dot (grey: tweet, green: mention, blue: retweet). As tweets are depicted chronologically, the x axis also marks a timeline. Taking up the user categories proposed by Group 1, we coloured red those accounts that we identified as automated in some form. Our initial assumption that automated tweeting follows a fairly stable, high-paced pattern was confirmed, but the Figure also helps to further specify this claim: among the automated accounts we found clusters of retweeting – the purple s-shaped dongles going up and down – which suggests that automated accounts do attempt to generate interactive behaviour. Automated activity, we suggest, can also blend into and mimic popular social media dynamics, and perhaps, indeed, it is exemplary of the reactive dynamics we noted above, reinforcing what is considered valuable sociality on Twitter.

Fig. 11.4 Automated activity pattern (created by Carlo De Gaetano (unfinished))

Social 3: How Social is a Hashtag?

While Groups 1 and 2 investigated the interactivity and activity associated with different kinds of Twitter accounts, Group 3 focused on the dynamics of content in our dataset of tweets on ‘privacy’. This group asked to what extent we can ascribe sociality not only to actors that are active on Twitter, but to the objects (content) with which they engage? This question draws on object-oriented approaches to social life developed in social studies of technology and related fields (Latour 2005; Lash and Lury 2007), in order to investigate the capacity of social media objects to organise sociality on Twitter. This group’s work was complicated by the fact that the definition of object-oriented sociality is itself called in question by social media analysis: should we define a Twitter object as ‘social’ when it facilitates enduring relations between actors and entities? Or is the cultivation of happening relations a sufficient mark of sociality? To investigate this, the group pragmatically decided to focus on a Twitter-specific objectual format, that of hashtags. Twitter studies have taken a special interest in the capacity of hashtags to organise social relations around and with objects, as in Burgess and colleagues’ (2015) work on the hashtag as a hybrid forum that facilitates the formation of ad hoc publics. Focusing on hashtags also makes it much easier to investigate content dynamics in a large data set, but it also means adopting a partial perspective on the data, as only 25% of the tweets in our datasets use hashtags. Accordingly, we approach hashtags, not as representatives of Twitter content, but rather as specific devices that enable the creation of relations between tweets, issues, and users.

Sociality, however, cannot be considered a given capacity of hashtags, and much hashtag activity is marked by efforts to achieve popularity, which Group 3 deemed not to qualify as ‘sociality’, since popularity is about gaining attention, not making relations. Following this intuition, Group 3 sought to move beyond the recurring popularity dynamics of Twitter by taking up co-occurrence analysis, a fairly common method in Twitter studies that applies measures of network analysis to words, and is used to detect the emergence of new relations between words or hashtags (for a discussion see Marres and Gerlitz 2015). Group 3 analysed patterns of co-occurrence between hashtags in the Twitter data set in order to see which hashtags were connected and how these connections changed over time. We divided our data set into four intervals, two before and two after the initial Snowden leak,10 and found a large number of promotional hashtags among the most connected terms.11 The group speculated about the ‘prize of success’. Where there is a broad uptake of a given term (such as ‘privacy’ after the Snowden leak) and accordingly a great potential for new relations, the consequence on Twitter is that the overall space of relationality degrades: generic, uneventful terms or promotional efforts take over, and these possess little apparent capacity to produce either enduring or happening relations.

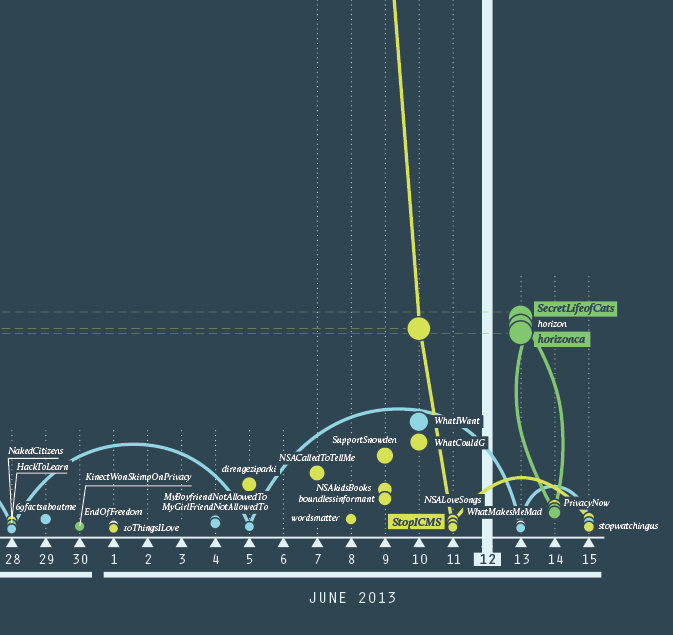

Fig. 11.5 Neologisms associated with #privacy (fragment of a visualisation created by Carlo De Gaetano)

A second answer to the question ‘how is a hashtag social?’ suggests itself in the form of hashtags containing phrases and jokes (e.g. #overlyhonestmethods; #igetannoyedwhenpeople, #markmywords). These hashtags indicate non-official uses of Twitter, and as such may be taken as an index of social activity, treating user invention as a marker of the social. To produce an overview of inventive hashtags, we considered the top fifty hashtags on each day of our selected period, retaining only those hashtags containing such invented language or neologisms. Figure 11.5 plots the occurrence of such invented hashtags over time, with the colours indicating four categories produced by Group 3 through a close reading of the relevant Twitter data: entertainment (white), politics (yellow), pointless babble (blue), and news (green). To be sure, these categories are not neutral: the category ‘pointless babble’ implies a devaluation of off- or random-topic commentary.12 And insofar as such off-topic commentary is common in social media, the use of neologisms points to medium-specific practices. However, at the same time, ‘pointless babble’ offers a useful contrast to political terms (I stand with Snowden), with the latter type becoming more prominent after the breaking of the scandal. It also usefully complicates our initial observation that newsworthiness and the widening of the topic space may translate into a reduction in the capacity to relate.

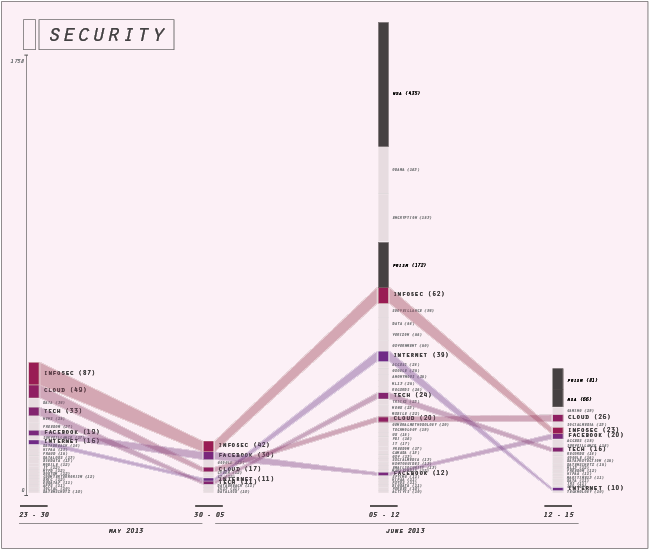

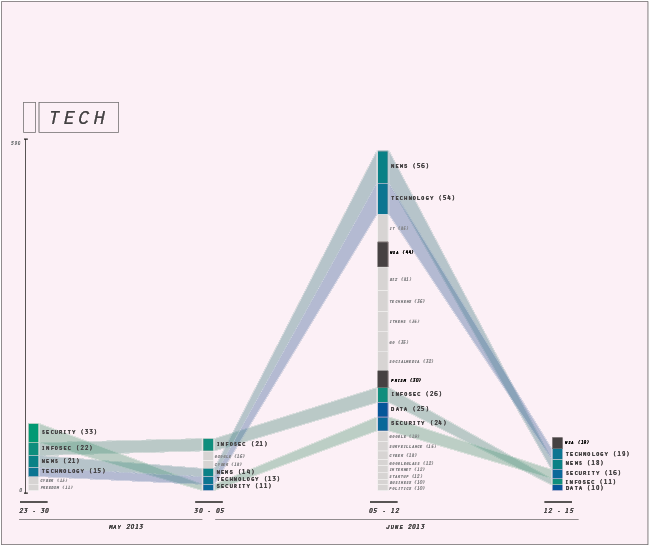

In a final step, Group 3 explored which hashtag relations in our data sets endured and/or varied over time, by mapping hashtag co-occurences in our data set. We speculated that hashtags more closely related to the news would be more ephemeral, appearing and disappearing in relatively quick bursts in accordance with news cycles. We thus selected a number of hashtags that were prominent in our data set across all the intervals and were not directly connected with the Snowden affair (that is, not ‘NSA’ or ‘Prism’, but ‘privacy’, ‘Google’, ‘security’, ‘surveillance’, ‘Facebook’, ‘tech’, etc.). For each of these hashtags, we produced an ‘associational profile’, a bar chart figure that shows with what other hashtags a hashtag co-occurs across intervals (e.g. Fig. 11.6, Fig. 11.7). We found that several hashtags’ associations remain relatively stable over time (coloured lines), with new associations coming in but not displacing these enduring associations in the third interval, when the Snowden revelations first broke (in grey).13 Exploring the distribution of enduring and emerging co-hashtag relations then led Group 3 to formulate two partly opposed indicators of sociality: firstly, the proliferation of neologisms, that is the re-appropriation of issues into everyday discourse, and secondly, enduring content relations which are not affected too much by news events and thus signal stable, institutionalised associations.

Fig. 11.6 Associational profile of #security (created by Carlo De Gaetano)

Fig. 11.7 Associational profile of #tech (created by Carlo De Gaetano)

Conclusion

Our summer school project moved from the definition of digital platforms as ‘social’ media to the experimental description of the forms of sociality one such platform, Twitter, enables. Our inquiries took as their starting point a sociological idea, namely the understanding of sociality as a distributed accomplishment, as something that happens among a variety of entities, and cannot be reduced to any singular entity, be it a collective of users, the platform or the content, or a singular conception of the social. This approach led us to produce what some may regard as rather artificial, counter-intuitive accounts of what is social about social media, as we produced the following list of potential indicators of sociality in social media: interaction, activity, creativity, and endurance. We do not claim that anything we detected on Twitter qualifies as the social, as we observed a series of competing, overlapping, and complementing socials. Our methods did not merely render them visible, but participated in their enactment.

However, our exploration of these proliferating socials did allow us to advance on the ‘problem’ with the ‘social’ of social media in two ways: first, it allowed us to elaborate a claim we presented at the beginning of this chapter, namely that social media are in line with the performative understanding of social life in some respects, but in other respects clearly go against it. In documenting patterns of interactivity, plotting automated accounts along a spectrum from human to non-human, and by tracing the happening of ‘content’, we produced what might be called ‘methodological stories’, that demonstrate how specifically social forms of life may be enacted in and with heterogeneous settings. We also formulated a problem with the sociality of social media of our own: one of the recurrent findings of our experimental exercise was what might be termed ‘frequentism’: we constantly faced the question of how to evaluate – and possibly adjust for – effects of volume. What to do with the ‘power users’ whose ‘size’ – in terms of followers, tweets, or mentions – crowds out and overshadows others? And what to do with the widely used hashtags that surface in our content analysis as a consequence of ‘bursts’ in retweet activity, not infrequently associated with automated accounts? Our heterogeneous group voiced different responses to such frequentism. According to some, ‘volume effects’ like the above obstructed our ability to detect sociality with social media. For others, however, ‘frequentism’ points to the heart of sociality in social media. It is what social media is all about: a new way of reaching and interacting with wider audiences without needing to pass via established gatekeepers (‘the media’). Automated tweeting raised similar tensions. Some proposed that automatisation could add to the accomplishment of sociality, enabling the creation of more diverse human-non-human relations, whilst others argued that automatisation undermines the possibility for social interaction and exchange in social media, as for instance in the case of promotional hijacking of popular hashtags.

Insofar as many of these empirical effects cannot be affirmed, but must be actively – and creatively – countered in digital social research, this form of analysis invites us to move beyond ‘empiricisation’ towards an ‘experimentalisation’ of the social. Such an approach makes the participation of social research methods in the making of sociality explicit: its task is to formulate methodological strategies that enable us to affirm the role of social research in the generation of its object of inquiry (Brown 2012). Instead of adopting a purely prescriptive position, that allows us to pass conclusive judgement on social media (‘this is not the social’), we see it as our job to participate in advancing alternative configurations of social media, and to specify alternative modes of digital sociality, ones that we deem more productive, caring, demanding, desirable, and so on. Social media ask us to move beyond prescriptive and descriptive forms of knowledge and to test alternative, more experimental forms of inquiry. Different forms of sociality cannot be held separate as easily here as in other contexts. As a consequence, social media lure us into asking questions we haven’t been trained to ask, questions that refuse a strict opposition between social realism and performativity, between independently existing societies and enacted heterogeneity (Mutzel 2009). How do bots participate in the society? Is automation – of all things – undoing the Thatcherite ‘there is no such thing as society’? Could social networks really help to organise heterogeneous collectives? Critical and creative approaches to social research and social theory, we argue, should do more with the ‘experimental’ capacities of the online platforms dubbed ‘social’ by looking for ways in which their methods could participate in the reinvention of the social.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants of the Detecting the Socials DMI Summer School 2012 project group. Our team consisted of: team users & interactivity: Rasha Abdulla, Davide Beraldo, Augusto Valeriani, Navid Hassan, Tao Hong, Johanne Kuebler, Carolin Gerlitz; team bots: Evelien D’heer, Bev Skeggs, Wifak Gueddana, Esther Weltevrede; team hashtag and issue profiles: Diego Ceccobelli, Catharina Koerts, Francesco Ragazzi, Andreas Birkbak, Simeona Petkova, Noortje Marres; design team: Gabriele Colombo, Stefania Guerra, Carlo de Gaetano; and the tech team: Erik Borra & Bernhard Rieder.

Notes

1 Savage (2009: 171) notes: ‘the social sciences, where mundane descriptions, evoking ordinary transactions, from websites, Tesco loyalty cards, CCTV cameras in your local shopping centre, etc., are the stuff of the new social. In these environments, the issue (to again evoke Walter Benjamin) is the mechanical reproduction of social figures, what might be seen as ‘the diagrammization of society’ which is the terrain on which sociology should now operate. The task of sociology might not be that of generating exceptionally whizzy visuals, using the most powerful computers or an unprecedented comprehensive database, so much as subjecting those which are routinely reproduced to critique and analysis. This involves making the deployment of these devices a subject of social science inquiry.’ Building on this performative analysis, we here argue for the need to engage, not just in empirical description, but also in experimental re-specification of sociality with digital technologies.

2 Successful entrepreneurship, Hutton claims, is about using frontier technologies to address human need and ambition.

3 Ryu, Janet (2010) ‘People You May Know: Helping you discover those important professional relationships’, <https://blog.linkedin.com/2010/05/12/linkedin-pymk> (accessed May 27, 2016).

4 Here we respectfully disagree with William Davies, who affirms the return of the social, but does not seriously consider its heterogeneity.

5 For a full description of the project, see https://wiki.digitalmethods.net/Dmi/DetectingTheSocials

6 This dataset comprises 919.234 tweets produced by 482.195 unique users. TCAT allows the creation of collections of tweets, and offers various of means of querying and analysing these datasets. It is available as open source tool on https://github.com/digitalmethodsinitiative/dmi-tcat

7 Reactivity is the term that economic sociologists Espeland and Sauder (2007) use to refer to the self-fulfilling prophecies that devices may produce when assessed entities reflexively adapt to their criteria of evaluation.

8 This information is provided via the Twitter Streaming API, and captures the software from which a tweet was send as named by the source or app creator.

9 In social media settings, the boundary between manual and ‘automatic’ is a fluent one. Services such as dlvr.it or U Tweet Deals allow for a broad array of automated actions, from automatic detection of trending hashtags, automatic replies or retweets based on keywords or hashtags, to automated account generation and more.

10 Interval 1: 23/05-30/05; interval 2: 31/05–05/06; interval 3: 06/06–12/06; interval 4: 13/06–15/06

11 Namely, the hashtags identified by Group 2 as stemming from automated behavior.

12 The entertainment category contains media entertainment and celebrity news (example: ‘it’s so sad that justin can’t even have privacy at his home #givejustinhisprivacy’). Politics comprises political topics and concerns (example: ‘#IStandWithEdwardSnowden because I believe in the fundamental right to personal privacy.’). The pointless babble category summarises all tweets that are not connected to news, issues or events but refer to vaguely connected private concerns (example: ‘#WhatIWant - Privacy. - a lot of money. - someone who will love me. - my parents to be proud of me. - high speed internet connection.’). Tweets labelled ‘news story’ refer to news-related hashtags (example: ‘I am disgusted at the BBC’s invasion of privacy. There must be a judge-led inquiry! #horizon #SecretLifeOfCats #horizoncats’).

13 Both hashtags #security and #tech are dominated by Snowden-related topics from the third interval onwards; other associations endure, as #security remains connected to #infosec, #cloud, #tech, #internet and various social media platforms. #tech continuous to share co-occurrences with #security, #infosec, #technology, #news, and #data, whilst #Facebook co-occurs with #Google, #security and #socialmedia.

References

Agre, P. E., ‘Surveillance and Capture: Two Models of Privacy’, The Information Society, 10.2 (1994), 101–27.

Baudrillard, J., Simulacra and Simulations (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994 [1981]).

Borra, E., and B. Rieder., ‘Programmed Method: Developing a Toolset for Capturing and Analyzing Tweets’, in A. Bruns and K. Weller, eds, Aslib Journal of Information Management, 66.3 (2014), 262–78.

Boyd, D.M., and N.B. Ellison, ‘Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13.1 (2007), 210–30.

Bucher, T., ‘The Friendship Assemblage Investigating Programmed Sociality on Facebook’, Television & New Media, 14.6 (2013), 479–93.

Burgess, J., A. Galloway, and T. Sauter, ‘Hashtag as Hybrid Forum: The Case of# agchatoz’, in: N. Rambukkana, ed., Hashtag Publics. The Power and Politics of Discursive Networks (New York: Peter Lang, 2015), pp. 61–76.

Callon, M., ‘Can Methods for Analysing Large Numbers Organize a Productive Dialogue with the Actors they Study?’, European Management Review, 3.1 (2006), 7–16.

Cetina, K. Knorr, ‘Sociality with Objects: Social Relations in Postsocial Knowledge Societies’, Theory, Culture & Society, 14.4 (1997), 1–30.

Cicourel, A., Method and Measurement in Sociology (NewYork: Free Press, 1964).

Coleman, G., Coding Freedom: The ethics and Aesthetics of Hacking (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013).

Couldry, N., and J. van Dijck, ‘Researching Social Media as if the Social Mattered’, Social Media+ Society, 1. 2 (2015), 1–7.

Crawford, K., and T. Gillespie, ‘What is a Flag for? Social Media Reporting Tools and the Vocabulary of Complaint’, New Media & Society, 18.3 (2016), 410–28.

Davies, W., ‘The Return of Social Government: From “Socialist Calculation” to “Social Analytics”’, European Journal of Social Theory, 18.4 (2015), 431–50.

Dijck, J. van, The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Didier, E., En quoi consiste l’Amérique: les statistiques, le New Deal et la démocratie (Paris: La Decouverte, 2009).

Espeland, W. N., and M. Sauder, ‘Rankings and Reactivity: How Public Measures Recreate Social Worlds’, American Journal of Sociology, 113(1) (2007), 1–40.

Gerlitz, C., and A. Helmond, ‘The Like Economy: Social Buttons and the Data-Intensive Web’, New Media & Society, 15(8) (2013), 1348–65.

Gerlitz, C., and B. Rieder, ‘Tweets are not created equal. Investigating Twitter’s Client Ecosystem’, International Journal of Communication, 11 (2017), 528–47.

Giddens, A., Social Theory and Modern Sociology (Cambridge: Polity, 1987).

Halewood, M., Rethinking the Social through Durkheim, Marx, Weber and Whitehead (London: Anthem Press, 2014).

Hargittai, E., and C. Sandvig, eds, Digital Research Confidential: The Secrets of Studying Behavior Online (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015).

Healy, K., ‘The Performativity of Networks’, European Journal of Sociology/Archives Européennes de Sociologie, 56.2 (2015), 175–205.

Hogan, B., ‘The Presentation of Self in the Age of Social Media: Distinguishing Performances and Exhibitions Online’, Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society (2010), 377–86.

Jones, S., ‘How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bots’, Social Media + Society, 1.1 (2015), 1–2.

Langlois, G., Meaning in the Age of Social Media (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

Lash, S., and C. Lury, Global Culture Industry: The Mediation of Things (Cambridge: Polity, 2007).

Latour, B., We Have Never Been Modern (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994).

——Reassembling the Social (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2005).

Lezaun, J., ‘A Market of Opinions: The Political Epistemology of Focus Groups’, The Sociological Review, 55.s2 (2007), 130–51.

Lury, C., and N. Wakeford, Inventive Methods: The Happening of the Social (London and New York: Routledge, 2012).

Mackenzie, A., ‘Set’, in C. Lury & N. Wakeford, eds, Inventive Methods: The Happening of the Social (New York and London: Routledge, 2012), pp. 219–31.

Marres, N., and C. Gerlitz, ‘Interface Methods : Renegotiating Relations between Digital Research, STS and Sociology’, The Sociological Review, 64.1 (2015), 21–46.

Marres, N., Digital Sociology: The Re-invention of Social Research (Cambridge: Polity, 2017).

Moor, L., and C. Lury, ‘Making and Measuring Value: Comparison, Singularity and Agency in Brand Valuation Practice’, Journal of Cultural Economy, 4.4 (2011), 439–54.

Niederer, S., and J. van Dijck, ‘Wisdom of the Crowd or Technicity of Content? Wikipedia as a Sociotechnical System’, New Media & Society, 12.8 (2010), 1368–87.

Osborne, T., and N. Rose, ‘Do the Social Sciences Create Phenomena?: The Example of Public Opinion Research’, The British Journal of Sociology, 50.3 (1999), 367–96.

Paßmann, J., and C. Gerlitz, ‘“Good” Platform-Political Reasons for “Bad” Platform-Data. Zur sozio-technischen Geschichte der Plattformaktivitäten Fav, Retweet und Like’, Mediale Kontrolle unter Beobachtung, 3.1 (2014), 1–40.

Papacharissi, Z., ‘We Have Always Been Social’, Social Media + Society, 1.1 (2015), 1–2.

Pinch, T. J., and W. E. Bijker, ‘The Social Construction of Facts and Artefacts: Or How the Sociology of Science and the Sociology of Technology might Benefit Each Other’, Social Studies of Science, 14.3 (1984), 399–441.

Rogers, R., Digital Methods (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2013).

Rose, N., ‘The Death of the Social? Re-figuring the Territory of Government’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25.3 (1996), 327–56.

Ruppert, E., J. Law, and M. Savage, ‘Reassembling Social Science Methods: The Challenge of Digital Devices’, Theory, Culture & Society, 30.4 (2013), 22–46.

Savage, M. ‘Contemporary Sociology and the Challenge of Descriptive Assemblage’, European Journal of Social Theory, 12.1 (2009), 155–74.

Slater, D., ‘Social Relationships and Identity Online and Offline’, in L. Lievrouw and S. Livingstone, eds, Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Consequences of ICT (London and New York: Sage), pp. 533–46.

Thielmann, T., ‘Taking into Account. Harold Garfinkels Beitrag für eine Theorie sozialer Medien’, ZfM, 1 (2012), 85–102.

Wilkie, A., M. Michael, and M. Plummer-Fernandez, ‘Speculative Method and Twitter: Bots, Energy and Three Conceptual Characters’, Sociological Review 63(2014), 79–101.