6

Outing Mies’ Basement: Designs to Recompose the Barcelona Pavilion’s Societies

Andrés Jaque

Fig. 6.1 Barcelona Pavilion, above and below ground (photos and composition: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

Fig. 6.2 Broken piece of tinted glass in the basement of the Barcelona Pavilion

(photo: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

Architectural practices are meant to engage socially through transformation of the social – whether by bringing in non-existing possibilities or reexamining old ones. Yet the field of architecture has often struggled with conceptualising the role of architectural practices within the processes by which associations rearticulate, particularly when dealing with the so-called masterpieces of modern architecture, whose exceptionality is often described as the outcome of their capacity to transcend the mundane. Among these masterpieces stands the Barcelona Pavilion, the 1986 reconstruction of the German National Pavilion, which was designed for the 1929 Barcelona International Exhibition by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich, major figures of the twentieth-century German architectural avant garde. After decades of influencing architecture, the 1929 Pavilion still stands, with its almost complete lack of furniture, as an exemplar of formal minimalism. In 1929, journalists could read its features as evidence of the Pavilion’s detachment from the ordinary. Rubió i Turudí described it as ‘metaphysical architecture’ that uses technique to ‘abandon the realm of physics’ and ‘detach itself from the social forces that originated it in the first place’ (Turudí 1929). This metaphysical interpretation has played an important part in shaping architectural critics’ understanding of the Pavilion. For instance, in 1979, Manfredo Tafuri described the Pavilion as a radically empty architecture available for whatever reality one could occupy it with (Tafuri 1979). This reading of the Pavilion is the one that most Mies-admirers participate in; the current daily management of the reconstructed Pavilion, which since its opening has functioned as an architectural monument open to visitors, has been designed to be perceived by visitors as metaphysical. This requires a great many design adjustments that must be imperceptible so as to make it seem that the Pavilion has always been read this way and, therefore, that the Pavilion does not seem designed at all. The following text provides an account of a number of architectural redesigns temporarily carried out in the Pavilion that were meant to challenge its daily management. All of them were effective to a certain extent in exposing the Pavilion’s daily life as a constructed process, rather than as something that occurred naturally, and its architecture as a momentous actor in the making of the milieu of associations the Pavilion exists by.

Mies-Knowing Society

Figure 2 is difficult to identify, but it was shot inside one of the best known and most photographed examples of modern architecture, the Barcelona Pavilion (built in 1986 according to designs of the architects Cristian Cirici, Fernando Ramos and Ignasi de Solá Morales). The Pavilion was conceived as a reconstruction of the Reich Repräsentationspavillon (the German National Pavilion), designed and built under the direction of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich as part of the 1929 Barcelona International Exhibition. According to the Fundació Mies van der Rohe, the public foundation that manages the building and its image rights, the Barcelona Pavilion caters to four main functions: (1) To be open to the public from 10am to 8pm daily, with a 10 euro ticket cost. Visiting the Barcelona Pavilion is a cultural activity that people interested in arts and architecture would plan when travelling to Barcelona. It is part of the informal curriculum most architectural students from European, American and Japanese schools of architecture are expected to be familiar with. (2) To be available for temporary rental. Parties, commercial photo-shoots, cultural happenings, product launches, and wedding receptions are some of the events hosted in the Pavilion that contribute to the building’s economic feasibility. (3) To serve as a location where town hall officials take visiting decision makers to provide them with evidence of what Barcelona is about, its capacity to successfully engage on international projects and its belonging to the historical making of modernity.1 (4) To be periodically photographed as a key piece of Mies van der Rohe’s work and to be included in publications circulated on- and off-line.

All four functions that the Pavilion performs play an important role in the making of what could be called ‘the distributed societies of Mies-knowing. This refers to the collective way that societies constituted by Mies’ buildings – as they currently exist, have existed, are reconstructed, or as originally envisioned by the various architectural offices and student groups Mies directed – associate with the fabrication, sorting, archiving, publication, distribution, surveying, exhibiting, celebrating, fictionalising or criticising of Mies-related entities. The participants in this conversation are the many people who are enthusiastic about Mies (who I will call ‘Mies-knowers’ from now on).

The Basement

Although visits, events, official tours and photographs are usually experienced as spontaneous registries of the ‘whole of the building’, they are actually the result of careful adjustments in the material constitution of the building itself, and of its daily maintenance, style and management.

The 1929 Reich Repräsentationspavillon only had a small underground receptacle, no larger than 5 m2, but its 1986 reconstruction included a 1050 m2, 2.4 metre-high mostly underground basement. The basement is not part of the visitor’s parcour. Until recently, it has never been included in the numerous circulating photographs of the Pavilion; nor has it ever been discussed by any of the many architectural historians, critics or theoreticians who have written about the building. Cirici, Ramos and de Solà-Morales initially conceived the basement as the place where the plumbing and the filtering equipment – which reclaims the water of the two ponds located aboveground – could be accommodated and reached for periodical maintenance, thus avoiding having to do work on the upper floor, which would affect the building’s visitors and events. However, the basement ended up performing many other functions as well. The broken tinted glass in Figure 6.2 was removed from the Pavilion’s aboveground floor when it was accidentally broken. In the same way, broken travertine marble slabs (Fig. 6.1) and ripped white-leather cushions that once were part of the upper floor’s decor are stored down in the basement once they are no longer pristine – to be replaced by identical-looking new ones, so that the upper floor never manifests the existence of accidents, breaking or ripping. Figure 3 shows a velvet curtain faded by the sun. It was removed, replaced by a new one, and put in the basement once it lost its uniform red color, in case its presence on the upper floor reminded anyone that the Pavilion has aged, and also to avoid any dissimilarities from photographs taken of the Reich Repräsentationspavillon on its opening on the morning of 27 May 1929, when only new materials where in evidence.2

The bottom of one of the ponds was initially covered with black acrylic panels that warped unexpectedly within a few months. They were replaced by glass panels and stored in the basement (Fig. 6.3). One of the stainless steel frames of the Pavilion pivot doors deformed due to its weight and eventually broke at its upper hinge. The whole door was replaced by one with a lighter frame and stored in the basement. Evidence of trial-and-error tentative material development are concealed in the basement, so that the upper part of the Pavilion can be acknowledged as resulting directly from Mies’ mind and thoughts.3

Fig. 6.3 Broken travertine slabs and remaining pieces of Alpine marble stored in the basement of the Barcelona Pavilion (photo: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

The basement also shapes the Pavilion’s association with different kinds of life. Early in the morning, before the Pavilion is opened to the public, Fanny Nole, a staff member (Fig. 6.6), removes the algae growing in the rainwater that accumulates in the holes of the travertine paving slabs, using for this purpose a Kärcher machine, which injects pressurised water into the holes, and then a vacuum cleaner. Both machines are placed in the basement before visitors are allowed in (Fig. 6.5). The basement is also the place where Nole has lunch, puts on her working clothes and rests. Figure 9 shows the hidden-in-the-basement machinery that filtrates and dilutes chlorine into the Pavilion’s two ponds. Figure 7 shows the place where the cat Niebla (Fig. 6.8) sleeps, eats and defecates. Niebla is taken to the upper floor every night to help prevent rodent infestation.

Fig. 6.4 Fading velvet curtain stored in the basement of the Barcelona Pavilion (photo: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

Fig. 6.5 Hoses, Kärcher machine, vacuum cleaner and mop in the basement of the Barcelona Pavilion (photo: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

Fig. 6.6 Fanny Nole (photo: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

Fig. 6.7 Niebla’s cat space in the basement of the Barcelona Pavilion (photo: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

Fig. 6.8 Niebla, the cat of the Barcelona Pavilion (photos and composition: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

Fig. 6.9 Filtering system in the basement of the Barcelona Pavilion (photo: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

Fig. 6.10 Removed plexiglass cladding in the basement of the Barcelona Pavilion (photo: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

Specific spatial, technological and performative design arrangements are carried out within/by the basement to remove algae and rodents from spaces where crowds use the Pavilion. To effect this, presences like the Kärcher, the vacuum cleaner, Nole and Niebla are convened to realise specific daily performances by which they engage with the Pavilion’s ongoing production. These performances thus include the temporary confinement of the Kärcher, Nole and Niebla in the basement, which helps to conceal from visitors the processes and performances by which the presences and absences of the rodents and algae – and of the Kärcher, Nole and Niebla themselves – are distributed and effected. One result of this is that visitors experience the appearance of the Pavilion as a given, one whose association with living beings is embodied in its design and not dependent on practices such as the ones that the Kärcher, Nole and Niebla perform daily.

Two architectural elements connect the basement with the aboveground part of the Pavilion, neither of which is suitable for human circulation: a spiral staircase and a dumbwaiter. The stairway’s headroom clearance fails to comply with architectural regulations and, together with the lack of a fire escape, makes the basement unsuitable for an occupancy permit. This could be seen as a design flaw, but it was actually an intentional decision taken by the architects to make it unlikely that in the future the Pavilion’s visitor tours would expand into the basement. Consequently, visitors’ unawareness of the basement was, so to speak, built into their relationship with the Pavilion.4

Carpets, lights, cables, microphones, chairs and other equipment used when space is rented out at the Pavilion is hidden in the basement when not in use (Fig. 6.12).

According to Víctor Sánchez, the Pavilion’s manager, no visitor has ever asked about the basement: ‘Visitors coming here already have a relationship with architecture and design.5 They already know the Pavilion. They know what it is that they come to see. They know what to expect. They do not ask, “What is going on?” or “What is it?” They just come, sit down on the benches. Some of them spend three hours like that. […] Our visitor is one that knows Mies, and one who knows that comes to see “nothing”’.6

Fig. 6.11 Broken door in the basement of the Barcelona Pavilion (photo: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

Fig. 6.12 Events equipment in the basement of the Barcelona Pavilion (photo: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

This ‘nothingness’ is the Pavilion itself, not as the all-above-ground-building that ages, breaks and fades, with spontaneously evolving aquatic ecosystems, mice and rats, produced in a tentative process of material experimentation, but as a two-storey building that is part of and contributes to producing a society of people, books, historiographies, and the performance of visiting the Pavilion itself. Thus visitors photograph it the way it is expected to be photographed, and photograph themselves within the interior of the Pavilion’s upper floor – all of them ignoring the existence of7 its basement, by which certain presences, and certain performances, are promoted and others evacuated. In this way the basement determines the Pavilion’s aesthetics and therefore the way its social dimension is sensed. It distributes visibilities and hides the evidence that prove the Pavilion’s materiality to be the result of an iterative experimental development affected by contingency and uncertainty, and evolving in time through processes of aging, accident and emergency.

Spotting the Flaw as Hierarchy-Maker Versus Social Multiplicity

The performance of interrogating the material configuration of the built Pavilion, in regards to the constructed-in-the-circulating-documents known Pavilion, when visiting the built Pavilion, produces a hierarchy among different ways of being a Mies-knower. Mies-knowers visiting the Pavilion often engage in a sort of ‘spot the difference’ activity that provides opportunities to acknowledge the superior competence of those capable of recognising small differences. The capacity to spot features – such as the fact that it was not the Philips-head screws of the 1986 reconstruction that were used in the 1929 Pavilion, or that the butterfly-like disposition of the onyx’s veins shows that it is not the one used in the 1929 construction – identifies particular Mies-knowers and specific ways of performing as a Mies-knower as advanced Mies-knowers. Hierarchy makes it possible for the Mies-knowing societies to avoid reading those differences as evidence of the impossibility of detaching the materiality of the Pavilion from the social dependencies and contingencies that shape it. Rather, differences are presented among Mies-knowers as mistakes (mistakes caused by a lack of knowledge or capacity to connect knowledge with design and construction on the part of the architects who reconstructed the Pavilion in the 1980s).

This way of assessing architects’ authority by their competence to recognise the reconstruction’s similarity or dissimilarity with the 1929 Pavilion played an important role in the decision-making process during the construction of the Barcelona Pavilion. In response to a scarcity of onyx in the last stages of the Pavilion’s construction in 1986, one of the architects proposed replacing that rare mineral with a large printout of photographed onyx. The architect’s supposed lack of engagement with what is generally considered to be the truthful materiality of the 1929 Pavilion is recurrently narrated in conversations as an evidence of his lack of ‘knowledge’ about Mies’ material sensitivity (Reuter and Schule 2008). As I interviewed different people involved in the daily running of the Pavilion, I was often told about this infamous architect’s cladding proposal, and was advised to discount anything this person might tell me related to my project.

In 1938, Mies van der Rohe patented, with Walter Peterhans, a ‘Method for the production of large photographs and negatives’, with the intention of using wall-sized photographs of precious materials as architectural components. This fact being a lesser-known aspect of Mies’ trajectory, most Mies-knowers are not aware of it. It would have been perfectly possible to recognise the discredited architect as a Mies-knower participant of an alternative Mies-knowing society, but this would have eliminated the hierarchy’s capacity to deny multiplicity among the Mies-knower societies.

The evaluation of the capacity to ‘find authenticity flaws’ among Mies-knowers – understood as their capacity to express disappointment when confronted with differences between the Pavilion as a circulating and discussed reality and the built Barcelona Pavilion – is performed by Mies-knowers as a means to collectively agree on how roles are distributed among different ways of performing as a Mies-knower and also as a multiplicity resulting from different ways of constituting Mies-knowing societies.

Other Mies-Knowers for Other Mies-Knowing Societies

The Pavilion is simultaneously part of many different social enactments. People often access the building trying to find a place to relax or talk after partying in Montjuïc. There are numerous cases of drunk youngsters trying to dive into the 30 cm-deep pond. There are also people who engage in gay cruising at night in its back garden, and others who enter the Pavilion searching for shelter from the rain. Homeless people use it as a place to sleep. Stray cats sneak in to drink from the ponds. A number of realities neither associated nor registered with/by the publications, the photographs, the narrations, the archives and the performances of the previously mentioned Mies-knowing societies are themselves enacting alternative ways of knowing Mies by registering it and visiting the built Pavilion, contributing to other possible Mies-knowing societies.

Fig. 6.13 Phantom. Mies as Rendered Society (photo: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

Fig. 6.14 Phantom. Mies as Rendered Society (research and drawings: Office for Political Innovation. Graphic design: David Lorente and Tomoko Sakamoto)

Fig. 6.15 Phantom. Mies as Rendered Society (photo: Andrés Jaque, 2012)

Fig. 6.16 Phantom. Mies as Rendered Society (research and drawings: Office for Political Innovation; graphic design David Lorente and Tomoko Sakamoto)

Taking the Basement Contents Upstairs

In 2011, the architectural office I direct, the Office for Political Innovation, was invited to intervene in the Barcelona Pavilion through a temporary architectural installation. Our intervention, called Phantom. Mies as Rendered Society, was programmed from December 13 2012 to February 27 2013. It consisted of two strategies: (1) Distributing a great selection of objects usually stored in the basement around the ground floor. Faded curtains, pieces of broken glass, broken travertine slabs, chlorine bags, the acrylic panels removed from the bottom of the pond, the Kärcher and vacuum-cleaner, event chairs, Niebla’s litterbox, and so on were set in the most visible parts of the Pavilion’s upper floor (Figs. 6.13, 6.14, 6.15), confronting the main axes of visitor movement in that area. (2) Maps of the installation were piled at the entrance and offered to visitors. The maps exposed the material histories of twenty-three objects (or groups of objects) taken from the basement to the upper floor, as well as the objects’ participation in extended social interactions (Fig. 6.16).

Three periods can be distinguished in the way the Pavilion’s societies evolved following the intervention. During the first weeks it was mostly Mies-knowers who responded to the intervention. Their reactions manifested the technologies and practices by which they engaged with the Pavilion, and this made it possible to track the networks that the built Pavilion is part of.

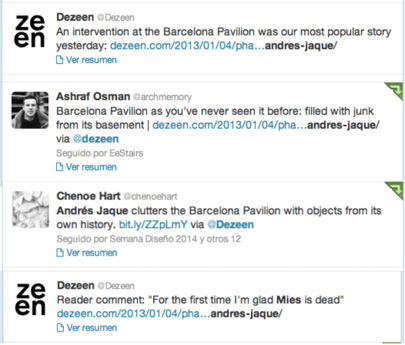

The intervention was temporarily ‘the most popular story’ in several design-oriented blogs (Fig. 6.17). The stories related to the twenty-three objects were not published online, but photographs of the intervention itself were published. The first reactions, prompted by photographs, were followed by fleshed-out reviews in architectural media by well-known critics, who contextualised the intervention within a number of specific architectural and artistic traditions8

Fig. 6.17 Comments in Dezeen reacting to Phantom. Mies as Rendered Society

The intervention succeeded in redistributing Mies-knowers visiting the Pavilion as participants in specialised Mies-knowing groups.

Group 1. A great number of visitors, not informed of the intervention, conspicuously complained of the way unexpected presences disturbed the experience they had anticipated, as an exacerbated version of the ‘spot the difference’ practice. In their complaints, Phantom was described as a ‘mistake’ and the result of a lack of competence on the staff’s part in their capacity to assess how to manage the Pavilion. As a result of their confounded expectations, a number of visitors, according to the testimonies of the Pavilion’s staff, engaged in actions that challenged the authority of the Pavilion’s custodians, such as refusing to pay to enter the Pavilion, or insulting them. The use of photographic cameras, however, often helped those same visitors construct their expected image of the Pavilion. By trying to find points of view in which the main features of the building could be photographed without including any of the objects added by the intervention, these visitors were obliged to experience the building in ways divergent from the usual visitor’s tour, in a kind of tactical displacement. The work of finding the place from which the expected image could be reconstructed through photography became a reconstructive performance itself, one that turned the ‘spotting the difference’ practice into a ‘removing-the-difference’ one, rendering uninformed Mies-knowers as constructors of the Pavilion as one coupled with its expanded Mies-literate accounts.

Group 2. This group comprised followers of architectural blogs who rapidly incorporated the intervention as part of the Pavilion’s temporary online social life. Reviews and images of the intervened Pavilion encouraged them to revisit it. They accepted the intervention as an extension of the Pavilion-knowing society of which they were a part.

Group 3. A number of interactions within online platforms frequented by Mies-knowers had the effect of expanding the intervention’s strategy and mobilising unnoticed parts of the Pavilion’s enactment. Many comments hosted information on accidents, unknown events or artists’ guerrilla works on the Pavilion. Outraged Mies-knowers, who considered the intervention to be misaligned with Mies’ ‘essentiality’, satirised the intervention by distributing images of compositions of what they would consider non-Miesian disgraceful technologies (including buckets, mops or Hello Kitties); they identified these technologies as disconnected to their shared notions of what Mies’ essence could mean, but by publishing these images they also made them visible, thus inadvertently creating a collective archive of the counter-Miesian.

Altering Labour Assessment

The relocation of a number of needed technologies on the ground floor, such as the vacuum cleaner, the Kärcher machine and the pesticides used by the Pavilion’s gardeners, transformed some of the Pavilion’s daily routines. Usually, the distinction between the custodial staff and the floor staff is clearly marked: there is a time for the custodial staff (before the Pavilion opens to the public, mainly consisting of cleaning) and a time for the floor staff (after the cleaning has ended). The two staff sections are also hired in different ways: the custodial staff is hired through a subcontracted company, which makes their jobs less durable and more sensitive to daily assessment, while the floor staff is hired directly by the Fundació Mies van der Rohe. The Foundation’s endorsement by both the municipal and the regional government means that the employment situation of the floor staff is more durable and less dependent on daily assessment. The intervention’s displacement of cleaning objects such as the vacuum cleaner, the Kärcher machine and pesticides rearticulated the way decisions were taken in regards to the way visitors experienced the Pavilion. Nole’s knowledge was needed in deciding where the machinery could be safely exhibited to visitors, and in weighing the risk of exhibiting pesticides within visitors’ reach. The presence of previously segregated agents in locations where they would have the opportunity to interact with visitors implied/required a redistribution of the roles played by individual staff members. If this could be seen as an opportunity for subcontracted employees to remain vital and enliven their jobs, it also worked the other way around. According to Nole’s testimony, a large part of her job was perceived by others as easy to do, whereas in fact she considered it tough and risky. She was responsible for the care of precious materials, and if things were damaged, she would likely be the one to take the blame. Due to the usual time divide between her job and the rest of the staff, others had never witnessed her working. When Nole’s work became transparent, any accidents that might occur – and according to her, ‘accidents are inevitable’ – would likely lessen her chances of retaining her job.9

The Stinky Water Dilemma

The displacement of objects made it more difficult to treat the pond water in the usual way. The water stopped being raked, and after several weeks leaves had accumulated and the water started to lose its clarity. Even though the intervention was originally met with great resistance among the directors of the Foundation, the support of art-interested board members, the media impact and the increased flow of visitors attracted by the media attention eventually caused the directors to celebrate the project. Once the pond was filled with objects from the basement, it became too difficult to rake the water. Most of the intervention’s transformations remained unnoticed by the Foundation’s directors, but there was concern that the water would start to smell, which obliged acknowledgement of the capacity for the intervention to result in actual, as opposed to merely symbolic, ecosystemical transformation. The Foundation perceived the smelly water as a problem that would unnecessarily deter prospective event-location seekers. But since the intervention had been officially presented as a culturally valuable art work, any action to remove the installation would make it seem as if the Foundation was not being supportive in its cultural program, and could even jeopardise its partnership with donors such as Fundació Banc Sabadell that had specifically supported the intervention. Two of the Foundation’s sources of income (rental of space and sponsorship) were jeopardised by incompatible versions of the built Pavilion’s ecosystems. The Foundation’s directors were paralysed by the impossibility of making a decision that would resolve the dilemma. The installation, for those Mies-knowers informed of its context within contemporary art, was already part of a Mies-knowing society, the one in which previous interventions in the Pavilion sponsored by the Fundació Banc Sabadell were already participating in a superadvanced Mies-knowing society. In a step towards a further layering of the Mies-knowers’ societies, for other groups of Mies-knowers the accumulation of leaves in the pond was turning the pristine Pavilion into what they would consider a non-Miesian swamp. No decision was taken, so the leaves accumulated until the day the installation closed. Once it was dismounted, the elements brought to the upper floor were taken back to the basement.

Whereas the 1929 German National Pavilion, as one of the preeminent masterpieces of modern architecture, has often been explained by architectural critics, such as Rubió i Tudurí and Tafuri, as an autonomous material entity operating beyond the mundane and the contingent, the role played by the basement of the Pavilion’s 1986 reconstruction shows the Pavilion as a socially distributed assemblage, one produced by the association of the building with humans, books, and documents circulating online. The design of the actual experience of visiting the Pavilion plays a key role in both stabilising the extended assemblage and enacting the process by which the evidence of its mundanity is excluded, hidden or policed as external to the assemblage or discredited as ‘mistaken’. The durability of this metaphysically-perceived assemblage depends on its capacity to keep its constructed condition hidden, a task that relies heavily on the basement’s performance.

The intervention Phantom subverted the long-running relationship between the basement and the upper floor of the Pavilion by exposing the way that the Pavilion, rather than transcending the mundane and deploying a capacity to accommodate the social, is itself the social and contributes to the making of the social. The intervention enabled this contribution to gain new layers of multiplicity by allowing the Pavilion’s assemblages to divide and increase, not least by drawing attention to the participation of the building itself. The intervention also forced the detachment of previously important contributors, such as Fanny Nole, from the Pavilion’s assemblage; for instance, in the way Nole’s involvement in the sensibility of the assemblage was challenged. Including the Kärcher and Niebla in the Mies-knowers’ aesthetics, therefore making accessible Nole’s performance, eventually excluded her from the assemblage. The dilemma of the stinky leaves shows the impossibility for design of delivering universal enrolment, and also demonstrates the role aesthetics can play in the daily competition between self-excluding assemblages, each based on alternative ways of sensing propriety (in this case, those based on the value of cultural experimentation versus those dependent on notions of celebration based on stereotypical sensorial comfort).

Notes

1 This practice started soon after the 1986 Barcelona Pavilion began construction, in the years that Pascual Maragall was the mayor of Barcelona. Cristian Cirici, architect and co-author of the 1986 Barcelona Pavilion in audio-recorded conversation with Andrés Jaque, 2011.

2 With the only exception of Der Morgen, a 1925 bronze sculpture by Georg Kolbe, that was considered the only ‘artistic content’ of the 1929 Pavilion. It is part of a two-piece installation, ‘Der Morgen und Der Abend’, placed at the Ceciliengärten at Tempelhof-Schöneberg, Berlin. It was temporarily included in the Pavilion and brought back to Ceciliengärten soon after the Pavilion’s dismantling.

3 ‘When it comes to take decisions about the Pavilion we try to put ourselves in the architect’s head [in Mies’ head]’. Marius Quintans, architect in charge of the Pavilion’s maintenance, in audio-recorded conversation with Andrés Jaque, 2011.

4 Isabel Bach, on-site architect during the construction of the Pavilion and the architect in charge of the maintenance after its opening, in audio recorded conversation with Andrés Jaque, 2011.

5 For those not familiar with the historiography of modern architecture, it is important to understand the relevance of the 1929 building and its circulation through all kinds of media in the construction of a shared discussion among most Western-educated architects. Photographs and plans of the Pavilion were included in the 1932 exhibition ‘Modern Architecture: International Exhibition’ at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which was remarkably influential in the formation of the modern canon. A black-and-white photograph of the Pavilion illustrated the front page of the catalogue of the 1947 exhibition that the Museum of Modern Art dedicated to the work of Mies van der Rohe, a catalogue that, according to most Mies’ historians, consolidated his image as it is currently known among many architects, and promoted Mies, by means of numerous technologies, as a ‘master’ of the modern architectural movement. The most relevant researchers of the work of Mies van der Rohe, including Beatriz Colomina, Caroline Constant, Michael K. Hays, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Philip Johnson, Franz Schulze, Manfredo Tafuri and Wolf Tegethoff have all considered that the extensive circulation of photographs, drawings, models and literary descriptions of the Pavilion, since its construction to the present, has made it the most quoted and the most influential of Mies’ works, a game-changing design that anticipates the work developed by him in different parts of the world after he moved to the US in 1937, and a formal and constructive model in the development of corporative, cultural, educational and residtential modern architecture since the 1960s.

6 Víctor Sánchez in audio-recorded conversation with Andrés Jaque, 2011.

7 ‘[Visitors] always make sure to have the building as a background in their photographs. Like it is happens in this case [pointing to a couple giving instructions to another visitor about the way to include a sculpture and a green marble wall as the background to the photograph the other visitor is taking of the couple]. It is often difficult to achieve, specially in the stairs. […] I guess it is the normal way for them to “access” a place like this’. Alejandro Raya in audio-recorded conversation with Andrés Jaque, 2011.

8 Axel N. (n.d.) and Pohl, E.B. (2013).

9 Fanny Nole in conversation with Andrés Jaque, 2012.

References

Axel, N. (n.d.), ‘Architecture and/of the Other. PHANTOM. Mies as Rendered Society by Andrés Jaque’, Quaderns, <http://quaderns.coac.net/en/2013/03/phantom-jaque/> [accessed 30 April 2018].

Pohl, E. B., ‘Il valore dell’infra-ordinario’, domus (23 January 2013), <http://www.domusweb.it/it/architettura/2013/01/23/il-valore-dell-infra-ordinario.html> [accessed 30 April 2018].

Reuter H., and B. Schule, Mies and Modern Living: Interiors, Furniture and Photography (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2008).

Rubió i Tudurí, N. M., Cahiers d’Art, 29 (1929), 409–11.

Tafuri, M., Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1979).