4

‘Teasing’

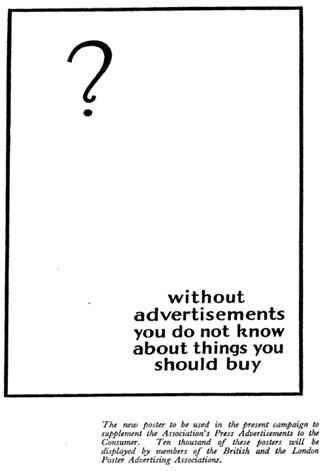

Window displays are clearly neither the principal nor the only way to arouse commercial curiosity. Contemplating a window display is always about being located at a precise moment in the trajectory of marketing objects and subjects, between past offers and future novelties; it is also always about having someone (or something) behind you as well as in front of you. Behind you, on the side of the street, and in public space, the window display is caught amongst the infinitely wider discourses of rumour, the press, and advertising; in front of you, on the side of the shop, and its private space, the objects shown in the window display are themselves enveloped in the more local coverings of packaging – covers that we must pass through should we want to consume them. I would now like to turn to these two spaces, which both prepare (in the case of advertising) and prolong (in the case of packaging) the curiosity operative in the window display.

I intend to demonstrate that packaging is a paradoxical driving force of curiosity. Packaging activates the tension inherent in every ‘re-presentation’ (Latour 1995). On the one hand, the text it features tells us what things are contained within. On the other, this text and what it says, cannot convey everything about these things and therefore cannot represent exactly what they are. It follows that packaging inevitably activates this tension, even if unintentionally: it creates a gap, a horizon of expectations, the desire to have things clear in one’s mind and to use one’s own senses to assess the balance between the cover’s promises and the properties of its content. Thanks to the invention of ‘teaser campaigns’, advertising takes advantage of this gap itself by re-enacting the spatial difference between the packaging’s outer message and inner content, in the form of a temporal gap between the promise being hinted at, and the promise being realised. It is these two methods of arousing curiosity that I would thus like to analyse, first by studying in greater detail the way they work, based on two suitable cases, then by considering one of their recent metamorphoses, which invites us to journey through a new ‘wonderland’.

Packaging (Teasing, Scene 1)

With only a few exceptions, packaging is as opaque as the window display is transparent. The box – by hiding its content, while at the same time providing a few indications about its nature and postponing the discovery of what is inside until later – uses Bluebeard’s three old tricks: an appeal to curiosity, the progressive revelation of content, and the preparation of a surprise. Packaging moves us towards making a purchase so that we can rip off the cover, just as the heroine in the story is always made to turn a key in order to be able to see what is on the other side of the door – with the associated pleasure and risk of surprise, which are to a person what the event is to a story.

Nevertheless, it is precisely concerning the surprise and its meaning that the tale and the packaging differ, or rather begin to differ. The tale makes a very clear choice to destroy the heroine’s dream with the occurrence of the ‘nasty surprise’, which we saw is also paradoxically an exquisite surprise for the reader: it is indeed the shiver produced by the unexpected discovery of the corpses that lends the tale its appeal, as if the taste for morbid spectacles at one time condemned by Saint Augustine had suddenly became acceptable, to the extent that it is offered to children. The tale therefore sets up a nasty-but-nice surprise, oscillating between the negative and positive according to whether we adopt the heroine’s or the reader’s point of view (this is a judgement that in turn can vary according to whether the reader himself identifies to a greater or lesser extent with the heroine1). Packaging sets up a far more complex set of operations, both regarding expectations and their satisfaction, given that fearing the worst and hoping for the best can, depending on the case, turn into a nice or a nasty surprise, or simply into a lack of surprise, when upon opening the box the buyer encounters a near-perfect match between the container and its content. Whereas the tale’s heightening of ambiguity only involves varying points of view, and while the nature of the final secret is utterly unambiguous – highlighted, in particular, by the repetition of references to ‘hooks’ – the uncertainties surrounding packaging involve the evaluator as much as that which is being evaluated: a judgement as to whether a surprise is ‘nice’ or ‘nasty’ involves both the multiplication of points of view, as well as the multiplicity of the objects being subject to inspection.

However, and contrary to the version of the tale set in stone by Perrault (which constantly repeats the same scene and is intended to be read identically), packaging confronts us with a far more fluctuating set of situations. The countless experiences of opening packaging have tended to bring about an evolution in the results of the task. Over time, a spectacular inversion between the proportion of nasty and nice surprises has been produced, in favour of the latter. How can we explain such an inversion? Historically, packaging was first perceived as an opportunity for potential fraud. By pushing the assessment of content beyond a commercial setting, the public was right to suspect that it was only being used to conceal a lack of correspondence between the proclaimed and actual content, to the benefit of the shopkeeper (Strasser 1989). Nonetheless, as irony would have it, through an extraordinary reversal that is integral to the functioning of the device itself – this is the first surprise of the surprise device – ever since appearing, packaging has actually presented itself as a tool employed for eradicating the fraud it was believed to supposedly encourage. Here, the word ‘reversal’ must be understood not only in the figurative sense of a turn of events, but also as meaning an actual inversion of the inside and outside, as if turning a coat inside out; as though the package’s content had migrated onto the surrounding surface, to the point that reading the text on the box becomes even more reliable than taking a detour into its content. In fact, packaging has the incredible virtue of being able to teach us more about the content it conceals than the content can do by itself: it enables us to be given information about a product that no sensory experience of the same unadorned product could ever provide us with, such as details about its composition or its origin. At the beginning of the twentieth century, in the context of major national legislation concerning product quality and safety – the French Law of 1905 on the prevention of fraud (Canu and Cochoy 2005; Stanziari 2005), the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act in the United States (Presbey 1929; Frohlich 2007), and others – the law turned these sorts of specificities into statutory obligations, and thus into contractual commitments. Instead of operating as an opportunity for fraud, packaging has become one of the best means of preventing it, given that once the information on the boxes had been signed with the manufacturer’s name, it offered the means of finding and punishing potential fraudsters, to the extent that now (and as was recently underscored by Alexandre Mallard (2009)), the scandals that we still occasionally encounter within markets (Besançon et al. 2004) are an exception to the ordinary situation, namely the most common, which rather demonstrates that extreme trust is the law of the market, and that breaking it is the exception.

From this point of view, social sciences lag behind the path pursued by the history of the market. Economic sociology (and more particularly the sociology of quality) has paid considerable attention to the question of information asymmetries, by focusing either on the economics of quality (Karpik 1989; Stanziari 2005), or the dynamics of product description (Callon et al. 2002; Cochoy 2002). In economics, information asymmetry is represented as a tool available to the seller that inevitably works against the buyer, as a perversion of the market: since we assume the actors are opportunists, the one who conceals something from his partner inevitably takes the opportunity to trick him for his own benefit, in order to achieve a larger profit. There is the canonical example of the used car market: in this market, the seller knows more than the buyer and, if the product is faulty, he will not hesitate to conceal this information and sell it at the normal price, thus making what is a dubious profit, to say the least (Akerlof 1970). In other words, in the economics of quality, the ‘surprise’ is implicitly assumed to be unavoidably ‘nasty’; in a market filled with rational actors, the partial concealment of an aspect of a real situation inevitably lends itself to the deliberate exercise of fraud.

However, with respect to these issues, economics, and even more so sociology, have intervened at the wrong time. When writing his famous article, even Akerlof conceded that actors on the ground did not wait for the formulation of his model before establishing their own diagnosis and developing sets of solutions that he is very honest to list: he mentions guarantees, brands, chains, certification systems – ‘even the Nobel prize, to a certain extent’, explains a mischievous note written by the prize’s future recipient, evidently reluctant to recognise the merits of certain laureates whose own arrogance is mocked in the article! How very unlucky: the one time an economist appeared to be receiving the unanimous praise of sociologists, to the point of becoming excited about the heuristic power of a pure, tough model, perfectly fashioned and indexed according to a series of extremely simplistic hypotheses, of the kind loved in economics and hated in sociology, no one – except the brilliant Akerlof himself! – noticed that this model had been obsolete ever since its creation. One does not need to be a specialist historian of the markets to know that the guarantees, brands, chains, and labels that Akerlof mentions in support of his argument are not his own inventions, but rather antidotes that have long existed as a counter to the emergence of opportunism in situations of informational asymmetry.2 In other words, the economics and sociology of quality are of very little use: their arguments and results are perfectly correct and even enlightening, but they are also completely redundant in relation to what actors (perhaps except for some of Akerlof’s colleagues) already knew, and were doing, long before their formulation.3

On the other hand, it is surprising to observe the extent to which these works have ignored the role played by the resource of surprise (this time in the positive sense of the word), even though the organisation of nice surprises is the only form of information asymmetry with which the professionals are still free to play, ever since the nasty surprise of fraud was seriously hindered by the mechanisms of contractual obligation that govern the management of packaging. The ‘nice surprise’ does however lend another sense to information asymmetry as desirable asymmetry, and in particular as information asymmetry desired on both sides: both on the supply side – proven by the recurrent use of contests, gifts, ‘bonuses’, praising ‘new releases’, and teaser advertising (see above) – and on the demand side, as revealed in the emblematic example of the receipt of gifts.

Box 2. The Gift Package: The Economics of Surprise

Within economic sociology, ever since Mauss, we have gone on endlessly about gift-giving. However, generally we have done so from a rather disembodied perspective, restricting ourselves to questions that are both accounting-related, involving the opposition between what is given freely and what is calculated, or social, oriented around gift-giving as the basis for a collectivity. More innovative works have demonstrated the extent to which gift-giving and market exchange, far from being mutually exclusive, are mutually reinforcing (Callon and Latour 1997). The gifts that circulate in the context of the market economy are an excellent illustration of this intricate relationship between gift and market; on the one hand because in this kind of economy offering gifts develops the underlying market, and on the other because thanks to the gift and counter-gift, presents themselves are a powerful vector of commoditisation and socialisation (Winnepenninckx-Kieser 2008).4 However, no matter what their merits, perhaps none of these approaches take into sufficient account the material nature of gifts.

However, taking their material nature into account allows us to be able to consider the relationships between gift and market differently. As these gifts very often appear in the form of packages, presents take us into an economy of surprise where, even before the delay separating gift and counter-gift occurs, the delicious suspense of discovering the former is in operation. Gift packages employ a form of hyperbolic informational asymmetry, given that they produce even more pleasure by being completely hermetic, opaque, and mysterious. More specifically, they appear simultaneously as a form of ‘anti-packaging’ and sublimated packaging. The gift is anti-packaging because it conceals everything and says nothing, whereas conversely, ordinary packaging shows almost everything and says a lot. However, it is sublimated packaging in that it takes the two fundamental incentives for packages to their limit, consisting in splitting the act of consumption in space by establishing a hermetic boundary between the container and its content, and in time, by separating the moment of purchase from that of consumption. This double characteristic of the gift package shifts the problems of the market and the gift somewhat: whereas the wrapping paper detaches the object from its market origins (Brembeck 2007), the curious excitement of unwrapping cancels out, at least for a while, the horizon of the counter-gift so as to focus the subject’s attention on the pleasurable struggle both with the wrapping and of discovering the object.5

Packaging (or arranging the surprise that goes with it) clearly brings the deliberate (or obligatory) exploitation of information asymmetry into play. However, it shows us that rather than inevitably leading actors towards valuing the lowest price, economic calculation can on the contrary inspire them to be honest and/or generous, to the extent that, in this case, rationally taking advantage of the information asymmetry leads, in a spectacular turn, not to the depreciation but rather to the preservation, or, in the best case, to the enhancement of the quality in question.

The preservation of quality is the most common. This is where the surprise (from the economist’s point of view, who is completely surprised to see calculation not being taken to its limit, despite such a wonderful opportunity to do so!) is the absence of surprise: this is the situation where the opening of a package confirms the accuracy of all the information intended to describe its content – as if the actors had not given into opportunistic temptation. In the second case, the package does not contain exactly what the packaging had promised, but this discrepancy operates in favour of the buyer, in the manner of a ‘nice surprise’. This surprise could take the form of a quantitative surplus – the package contains more product units than indicated on the label – but also a qualitative gain that is rarer and/or harder to assess, when the product is decorated with, or accompanied by, more qualities, objects, or services than the label was able, or wished, to announce. In each of these scenarios, it is as if the logic of the ‘efficiency wage’, dear to labour economists, had migrated towards the market for goods and services, in the form of an ‘efficiency bonus’. In the same way that in the labour market the payment of a salary above the market rate allows an employer to expect greater commitment from his employees (Shapiro and Stiglitz 1984), going beyond the promises of the packaging is to play on the strengthening of customer loyalty. Who has never experienced the satisfaction of discovering that an ordinary product bought at a cheap price was much better than its packaging and/or price might have led us to expect? It must be noted, however, that very often actors find it difficult to resist the temptation to reveal the logic of this bet after its implementation (like a secret we cannot keep), either directly, with comments such as ‘X% extra product free’, or indirectly, and in a way that is perhaps more rhetorical than literal, as exemplified by the hilarious tics of ‘Monsieur Plus’, the hero of the famous adverts for the Bahlsen cookie company.

Fig. 6. Monsieur Plus, Bahlsen6

What the information asymmetries in packaging employ most often, however, are neither errors of judgement, involving mistaking a poor quality product (in Akerlof’s case) or a more abundant or better quality product (in the case I just mentioned) for the standard product, nor the hope of consumer loyalty or a repeat purchase if they are satisfied, but rather the excitement provoked by the promise of the packaging and the obstacle that this nevertheless presents. This gap establishes a differential; a tension, in the physical sense of the word, whose emergence often calls on desire to resolve it. In this case, the surplus value attached to the use of informational asymmetry is quite different from the pattern described by Akerlof, both in terms of supply and demand. On the supply side, this surplus does not lie with the negative or positive variation of the content’s quality but rather in the ‘game’ played by the packaging itself: it offers both the potential for a mismatch and/or fun. On the demand side, this surplus activates an asymmetry which differs from classic forms of information asymmetry. Whereas the latter is not perceived by the customer, the new asymmetry is, on the contrary, sensed as an expectation of ‘something different and desirable’ that nevertheless remains, if not a mystery, then at least an object worthy of discovery. The added-value here does not stem from a particular input but rather from the input of novelty or the hope of novelty. The device is very close to the excitement of a striptease, which draws the spectator into being involved in an enjoyable sequence of expectation and discovery, as we shall see from following a 1955 campaign carried out by Kellogg’s (the cornflakes manufacturer) in order to promote a new form of packaging design.

The choice of cornflakes is all the more significant as this product played an emblematic role in the history of packaging. The Quaker Oats company, to make a profit out of investments in expensive machinery designed to guarantee continuous production, had the idea of packaging its product to distinguish it from other cornflakes, which tended to be lower quality and sold loose. This enabled them to combat fraud by establishing competition oriented around quality, to invent a market for breakfast cereals, to promote their brand name, and to conquer the whole American market via its national advertising campaigns (Chandler 1977). Along the way, the development of breakfast cereal played a decisive role in extending the activities not only of cereal farmers, but also of the railways that assured its national distribution, as well as in both the growth of the paper industry involved in manufacturing the cereal boxes, and the considerable expansion of magazines responsible for advertising (Presbrey 1929: 438).

Packaging transforms a logistical constraint into a playful device. As in a striptease scenario, it manages to convert the fleeting encounter between a consumer’s gaze and a richly coloured scripted surface into a scenario seen as likely to extend over time. This is what is clearly demonstrated by the rhetoric of the Kellogg’s packaging which consists of a representation not only of the product, but also its origins (a fresh bunch of grapes), and its destination (an appetising bowl of cereal with raisins).

.jpg)

Fig. 7. The Progressive Grocer, December 1957, p. 38 (detail)

By proceeding in this way, this packaging breaks from the product’s lateral position amongst its competitors and enrols the consumer in a longitudinal and longer-term experience of consumption. From this perspective, the device genuinely employs a technique of manipulation. For the psychologists Beauvois and Joule (1987), manipulation refers to any strategy designed to lead people into doing something that they would not have done spontaneously, but without either forcing or duping them. The trick is sequential: manipulating someone consists of involving them in a step-by-step decision-making process. Over the course of the process, people will obtain all the information they need in order to make a rational choice, but they will only receive it progressively. The most appealing information is provided at the beginning, whereas negative information is only revealed at the end, before the final decision. Experiments show that once people have been attracted to and are involved in the decision-making process, they find it difficult to go back and abandon choices that were previously considered, even once they eventually possess those elements in the assessment that, from the perspective of a purely rational choice, should lead them to abandon their initial plan.

The ‘raisin bran’ packaging clearly places the consumer within this type of sequential decision-making process. However, in this case, the manipulation is reinforced from two sides. The first reinforcement involves a subtle temporal trick. What should logically be considered as the first stage in a sequence of manipulation – that is to say, the initial offer made to the consumer – intervenes here as the second stage, in a longer story that links consumer and product even before they have encountered one another in the shop. In fact, in the imagery of the lovely bunch of fresh grapes, the consumer is meant to understand that she or he is already implicated in the product’s lifecycle. Thus, from the moment of the first visual contact with the packet, the subject is already being drawn in. In other words, the consumer is discreetly led into following the logic of a striptease, in a literal sense, in which excitement comes from reading, ordering, and working out the promises associated with the progressive discovery of vignettes within a very real ‘storyboard’. He is at the very centre of a linear story that moves from production (the grapes) to consumption (the cereal, raisins, and milk in a bowl), while being invited to complete this story, and to commit himself to the next stage of buying the packet so that the narrative – running from production to consumption, via the purchase – becomes well-ordered. This is how real life corresponds with the life that is depicted. This is how desires and promises are fulfilled. Everything happens like in a game of strip poker, in which players have to ‘pay to see’ the cards (open the box) so as to discover what the story is all about.

The second reinforcement stems from the customer’s cognitive enrolment. Paradoxically, the packaging’s material striptease is both much ‘hotter’ and more universal than the sexual striptease of specialist clubs. It is much hotter because, with the packaging, the (usually male) spectator is not restricted to passively watching a striptease. On the contrary, he is invited to take part, to get to grips, physically, with the performing entity, as if the spectator were able to touch and undress the striptease artist and even leave the club with her in order to continue the operation at home. It is far more universal as it is neither limited to an adult audience nor in any way towards a single motivation. On the contrary, it is addressed to men and women, adults and children: anyone who finds themselves attracted to a very long list of motivations and pleasures.

Far from being a fragile metaphor arbitrarily chosen to deal with the appeal of packaging, the logic of the striptease is clearly the pragmatic logic which professionals themselves use, as we can see from the entire advertising insert from which my example is taken, shown here:

.jpg)

Fig. 8. The Progressive Grocer, December 1957, pp. 35–40

This Kellogg’s advert is presented as a six-panel ‘storyboard’ published in the magazine The Progressive Grocer. The wording of the advert consists of a spectacularly reflexive and ‘back-to-front’ use of the striptease: each of the new elements and advantages of the new packaging are presented in sequential fashion, in a folded leaflet that ranges from employing ‘nudity’ to the ‘appropriate clothing’. The sequence begins with an intriguing cover that at first conceals everything else, as long as the leaflet remains folded: that of an enigmatic ‘naked box’ with only the Kellogg’s logo visible. This logo is repeated obsessively on the box’s surface, like the texture of a skin, or as if it had been drawn by Andy Warhol, the artist of the moment (particularly in the advertising sector!). An unknown hand deepens the mystery of the packaging by placing a first ‘garment’ onto the box: ‘Fresh from Kellogg’s of Battle Creek: Packaging with a Purpose’. But what purpose? It is only by unfolding the leaflet that in the next three panels we discover (in the real sense of the word) a set of similar boxes, this time modestly covered with product names and graphic illustrations, which gradually reveal themselves bit by bit. The world of clothing is not only suggested by the supportive navy-blue velvet in the background, but also by presenting the products according to the logic of a real fashion show, with all the elements that make up the complete collection of cereal boxes being exhibited from left to right. Finally, the last two panels, covered with text, reveal the deeper meaning of the Kellogg Company’s ‘purpose’: the fifth page announces that ‘The purpose of these new packages is simply to sell; to sell the fastest selling cereal even faster. Faster selling for you, for us – faster buying for your customers. Everyone benefits. These new ‘bank note’ packages on your shelves are as good as money in the bank’. The last panel provides impressive evidence of the scope of its campaign: ‘Biggest ad campaign ever: Selling to 160 million people’, and so on. This advert is aimed at professionals in retail distribution and in making profit; here it is Kellogg’s that is trying to tease the grocers so that they, in turn, can tease the consumers, so that ‘everyone benefits’. By proceeding in this way, the campaign partly reveals a final game of bodies and clothes, in which each market actor and mediator hides behind the other: the grocer behind the consumer; the manufacturer behind the grocer; the trade press behind the consumer; the grocer and the manufacturer; and on and on (Cochoy 2008b).

In the final analysis, product assessment involving the progressive revelation of packaged information does not have to be abstract, cold, and descriptive, distant from the ‘flesh and bones’ of products. On the contrary, thanks to the curiosity that is aroused by this way of getting to know economic objects, the packaging itself becomes as warm and tangible as its content. Through curiosity, packaging tries to build ‘attachments’ (Gomart and Hennion 1999); it tries to warm up the relationships of consumption; it attempts to help us find the sensory glow of the goods that, throughout its history, it has tended to conceal (Cochoy 2004). Packaging does this by showing the products directly through narratives, through appealing arguments, and representations, or, indirectly, by playing with ideas, values, identities, and symbols.

The Kellogg’s advert, however, acts as a hinge between two devices: on the one hand, it features packaging and the ways in which it can be designed so as to magnify the power of seduction; on the other, this scenario is itself presented as an advert, whose discursive trick consists in intensifying the narrative sequence that is inherent to this specific form of packaging, while using the same type of procedure, albeit this time applied to advertising. We thus understand that the methods for arousing curiosity are layered, involving not only a game at the level of each constituent element – window display, shelves, and grocer’s bank account; the brand, product description, and box’s contents; the discourse, the ‘storyboard’, and how the advert unfolds – but also the ordered way in which these themselves are ‘packaged’; the forms of advertising that cover the commercial spaces that enclose the forms of packaging that, in turn, house the product.

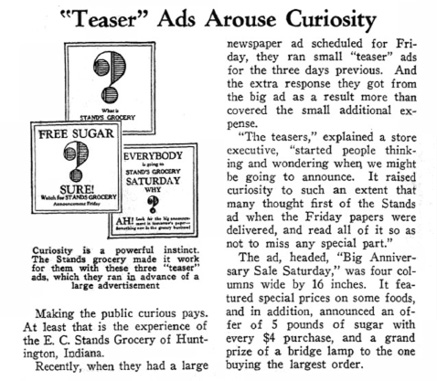

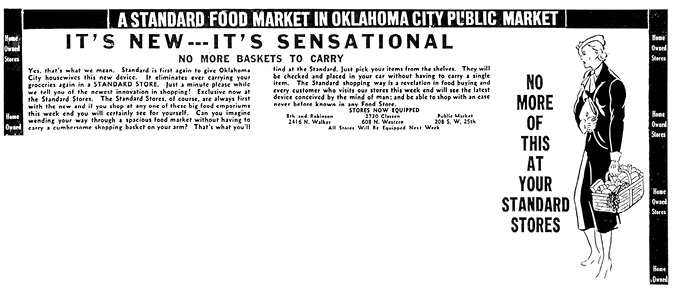

Advertising (Teaser, Scene 2)

The advert thus occupies a position that looks over others,7 giving it a particularly unique role in terms of instigating commercial curiosity. The carnal game of unpacking the multiple layers inherent to packaging is in fact often largely prepared further upstream by the advert that appears like a first virtual envelope, a first appeal, and a first piece of bait in the game of arousing curiosity. With the first veil of the advert lifted, people should be led into removing, one by one, the other layers that separate them from the product they desire, or are made to desire. However, this game reaches maximum intensity when the advert itself, even before it has indicated the other coverings that are its very job to point towards, mimics the next game, becoming no longer just a metaphorical striptease, as with the Kellogg’s packaging, but sometimes a literal striptease, as in the case that follows. It is this spectacular manner of arousing curiosity that I would now like to focus on, by examining an extremely famous advert that – at least in France – is considered to be an archetypal masterpiece of ‘teaser’ advertising (Lendrevie and Baynast 2008).8

This advert, known as Myriam and remembered by all those who lived through the beginning of the 1980s, consisted of a series of mysterious posters that appeared at the end of August 1981, on 900 4 x 3 billboards across Paris and six other French cities (Le Monde 1988; Devillers 2001; Mantoux 2010). The first poster shows a pretty woman in a green bikini with a beach in the background, between a blue sea and sky. This anonymous person announces, in an inset that acts as a speech bubble: ‘On 2 September, I’ll take the top off’. No other information is given on the poster: just as we do not know the names of the blue-bearded man and his wife, we do not know the name of the model in the green bikini, or of course the advertiser’s identity and intentions. On 2 September, we find the young woman in the same place and the same position, except that she has indeed removed the top half of her bikini and has thus unveiled her bosom. This new shot announces: ‘On 4 September, I’ll take the bottom off’. The fascination of this slow-motion ‘soap opera’ and the incredulous anticipation of full nudity, as presaged by the initial promise, inevitably leads to major questions in both private and public, echoed in the media, as people excitedly await the day after tomorrow. On 4 September, Myriam does indeed take off the bottom of her bikini. However, this time the photograph is taken from behind, with the comment: ‘Avenir, the billboard company that keeps its promises’.9

.jpg)

Fig. 9. Avenir, the Billboard Company that Keeps its Promises

The singular notoriety of this campaign is no doubt connected to its extraordinary ability to bring together (in one space and with astonishingly few means at its disposal) an impressive number of resources to support its effectiveness. As we shall see, these resources, which constitute a veritable grammar of curiosity, are at once fun, logical, mathematical, linguistic, semiological, anthropological… and even physiological, mechanical, pragmatic, humorous, and magical!

With Myriam we once again encounter a dimension of the game that we discovered in the window display, although here divination is replaced by the riddle.10 The game draws together charades and logical inference. As we know, charades involve setting two riddles, one concerning the whole, the other concerning each of the elements intended to lead to that whole. Here, the mechanism is similar: the context of city billboards invites passers-by to assume an overall meaning – if it is an advertising campaign, it must be trying to sell us something, but what? – and thus invites them to consider each of the posters as a clue to the whole they have to find.

It is here that logic intervenes. Everyone understands from the outset that the game’s outcome is based neither on chance, nor, as in a competition, on a personal appraisal, but rather on producing endogenous knowledge, whose elaboration the messages suggest bit by bit. This ‘involves’ passers-by in the co-production of meaning over the course of a real experiment, which consists of the posters’ successive proposals and the hypotheses and the verifications made by the reader. The logic at work is very similar to that of a recursive mathematical series; that is, a calculative rule in which each natural number n is associated with a specific real number, whose value is determined by those previous occurrences. Conversely, when we know the successive values in a series, we are quickly led both to work out the underlying calculative rule and to anticipate the elements that will follow according to this rule. Therefore, when I see a series of images, each of which represents a body adorned with a set of items but each time stripped of one once compared to the previous image, I am logically led to anticipate, at least as a mental hypothesis, the third stage, the naked body that is, since it is all that is left after the removal of the solitary remaining element. And I am all the more likely to follow the series given that each image provides me not only with a succession of values, but also a calculative rule, allowing me to predict their succession: ‘every two days the image will be the same as the previous, minus an item of clothing’ or, to put it in mathematical terms, ‘for the series of a number of garments, U, for every U of rank n, the value of Un equals Un-1-1’.

This logical-mathematical device is reinforced by another device, this time linguistic. In a sense, this should not be surprising: all things considered, the traditional opposition we usually establish between the ‘literary’ and ‘mathematical’ worlds does not hold, given that mathematics is purely a language, and that language, on the other hand, only has meaning by virtue of meaning, in other words because of the logic it is responsible for establishing and conveying. Nonetheless, the interweaving of the games of series and language at work in Myriam is rather unusual. This advert is based on a succession of promises that are each either followed or accompanied by the realisation of the precedent. Now, we know that in linguistics, a promise is a pure example of what can be termed a performative utterance, as opposed to a so-called constative one (Austin 1961). Whereas the latter establishes a link between itself and the world that is either correct or incorrect (for example, ‘I am wearing a bikini’), the performative utterance refers to a world that is neither right nor wrong, but which it contributes towards realising (‘I promise that on 2 September, I’ll take off my bikini top’). Utterances of this kind – called ‘speech acts’ because of their ability to have an impact on the world rather than describing it – have two dimensions. The first, termed ‘illocutionary’, is inclined towards the utterance itself, given that it specifies the intention (in this case, a promise; in others an order, a threat, and so on.). The second, termed ‘perloctionary’, is by contrast inclined towards the effect produced by the utterance (for example, the belief in the promise, or its actual delivery). What is particular about the pattern in Myriam is that, after the second poster, each promise is accompanied by the previous one being realised: if, for each promise P, of rank n, in which * marks a promise delivered, the resulting sequence is P1 ; P1* + P2 ; P2* + P3, a sequence which refers to a more general structure that we can write as P(n1)* + Pn. Roland Canu, in the conclusion of a study demonstrating the importance of decisions and prior constraints in the development of an environmental labelling device, noted that ‘certainly, saying is doing, however just as often it is having done’ (Canu 2011a). In our case, on each occasion, saying means having done but also doing, and it is doing with all the more certainty given that we have shown that we have done so before. In other words, with Myriam, what was said plays a role in what is said: for every event that follows, the fulfilment (performation) of the previous promise increases the performativity of the next. The method is all the more effective as the statement involves both the anaphoric repetition of a strictly identical structure – ‘on (date X) I will take off (clothing Y)’, reinforced by the visual anaphora of an unchanged scenario, and the variation of its referent – on each occasion, the date and clothes change.11 Here we find two conditions that are essential for the performativity of certain language acts. The first is their continuous reiteration, allowing the words to ‘take shape’ and the ‘bodies’ to exist through these words, without which they would amount to very little (Butler 1988). The second is the language’s ability to act as the world’s ‘ventriloquist’, making it speak and express its power not only through its words (Cooren 2010), but also through the intervention of ‘wordjects’; that is to say, objects that are articulated like words (Cochoy 2010a).12

Nevertheless, the playing of the game, the use of logic, and the reception of performative language together produce a disturbing result, given that, rather than bringing us closer to the product, they lead us to anticipate the model stripping completely, without being able either to discern the intention or to believe it possible, ‘all moral standards and advertising logics being equal’. In fact, as the campaign progresses, social conventions, the rules applicable to advertising, and, more generally, the laws penalising indecency, render each promise more unlikely than the previous.13 Undoubtedly, showing bare breasts is not without scandal, but, as an act, it does seem to have reached the pinnacle of possible licentiousness, to the extent of making further transgressions simply unthinkable. This was 1981, that is to say a time when the topless trend, while widespread (Kaufmann 1998), was also far from the ‘porno chic’ that was to follow (Heilbrunn 2002), and a period in which feminist criticism seized on advertising and when the law governing it underwent significant development (Parasie 2010).

Furthermore, advertising cannot, by definition, be anonymous and free: the person bearing the cost of the campaign has a brand to promote and a product to sell, so displaying nudity for free hardly seems compatible with the rationality of advertising inherent to urban billboards. That said, the three stages of undress are compensated for by three other layers that act to minimise the scandal: firstly, the era of bare breasts bolstered public tolerance for such displays; secondly, the beach featured in the background places the foreground (the naked breasts) in an everyday accepted context (Kaufmann 1998); lastly, the contextual framework of the billboard isolates the message within a space of expression which, because it appears in the public space of the street, enjoys the licence afforded to advertising professionals. Nevertheless, this licence remains subordinate to forms of legal regulation that remain vague and unstable, largely contingent on complaints and case law (Iacub 2008; Cochoy and Canu 2006). Because of this (given the time, place, and the way the act of viewing is framed), everyone understands that the second poster takes the exhibition of the body to the limit of acceptability;14 beyond which it would almost certainly tip over into scandal and transgression, especially for the person who remains stubbornly and determinedly stood in front of us, and whose legs are also slightly apart,15 according to a staging that was accurate to the millimetre:

It was very easy, but very precise, so he [the photographer] already knew exactly where I should place myself […] there was a picture that had been done beforehand, and we just copied the picture exactly (Author’s interview with Myriam).

In other words, what is logical when inside the frame is not logical when outside it, or when trying to deduce the next phase: the performative virtues of the successive statements, at least from the second poster onwards, come up against the ‘infelicitous conditions’ surrounding them, which cast doubts on the performance that is promised. It is precisely this blurring of mathematical logic, linguistic performativity, and social routine that makes the campaign either so attractive or so disturbing, by taking curiosity to its limit. The cognitive dissonance between performative logic and the social-legal-economic conditions that limit the campaign plunge the passer-by into a whirlwind of calculations: They wouldn’t really dare? Who are they? What are they looking for? What is the meaning of all this? Where are we going? Is it tolerable? There must be a trick, but which one? Gradually curiosity becomes a plot, both in the sense of a story and an enigma. As the plot proceeds, a hypothesis of humour germinates as something of a saving grace. Tinged with both anxiety and pleasure, it is the small act of complicity often associated with advertising (Parasie 2010), consisting of joining in the game of co-producing the message, both in order to understand it and to be reassured (Cochoy 2011b).16

One of the remarkable aspects of the plot lies in its particularly distended and discontinuous nature. We find here a mode we had come across in Bluebeard, in which certain passages stretched time with the help of remote dialogues, delays, anaphora (Anne, sister Anne…’), and others (see above, chapter 1). However, with Myriam, the method becomes exaggerated. With every poster being replaced every two days, it is as if the story had been divided into a corresponding number of sequences and was delivered across a number of episodes as a soap opera. This way of working introduces a radical alternation between statement and reception. The method first requires personal and emotional involvement. As successive posters each ‘press pause’ for two days, it becomes possible for passers-by to come across them in several different places, to pass in front of them several times and thus to experience the message, and be moved and/or made to think about it before the next is discovered. Above all, this ‘pause mechanism’ enables a move beyond the bilateral relationship between transmitter and receiver that is characteristic of advertising. The sequence and the emotional charge, doubled by the suspension of time, provide the opportunity for the activation of a multilateral relationship: each person, confronted by his or her own perplexity and feelings (curiosity but also rejection, incredulity, disapproval, amusement, excitement…) has the possibility of sharing these with their loved ones and thus becoming involved in the creation of collective interpretation and judgement through their shared curiosity.17 To put it in Durkheimian terms, the unfolding proliferation and suspension of the campaign puts to the test a strong and definite state of collective emotion. Rather than being only commercial, the production of advertising is also (above all?) social. Perhaps more than other consumption practices (Gaglio 2008), this type of media in fact has an astonishing ability to test social norms on a large scale; it allows limits to be explored, for their basis to be expressed, and for experimentation with future potential developments. Advertising works on the relationship to/with values; it excites its audience and at the same time triggers conversation, indignation, and a desire for reassurance. By creating the conditions that encourage debate, the Myriam soap opera, both in terms of its content and the time available, is the forerunner of today’s ‘buzz’ and ‘viral marketing’ (Mellet 2009). In fact, the campaign’s scandalous and mysterious nature – each time giving the public and the media two days for emotions to be stirred up – also brought considerable press coverage. This spread the message free of charge and maximised public attention as both a positive externality and an echo chamber, resulting in the transformation of a private, individual curiosity into a curiosity that was public and collective:

The irony of the story is that the campaign only ran for ten days. Everyone felt sure they had seen it… whereas most people only learnt about it when they saw the pictures in the papers! (Mantoux 2010).

Some people discerned that behind Myriam becoming a ‘social event’ lay advertising’s pretension or ability to establish itself as a cultural phenomenon. There are many works that refer to advertising as a matter of ‘culture’, both negatively, when criticising the medium for commercialising artistic codes, for contributing to the political economy of symbols (Baudrillard 1981), and for promoting ‘marketing ideology’ (Marion 2004); and more positively, when highlighting the creative contribution of advertisers (Gaertner 2010), and when bringing to light the important cultural role played by advertisers, on the sides of both supply and demand (Marchand 1986; Sauvageot 1987). This said, the ‘ad culture’ should be understood as they do in the French-speaking life sciences: rather than a cause that produces an effect, the ‘cultural’ dimension of Myriam is rather the result of ‘cultivating’ the public, analogous to the ‘cultivation’ of yeast in a petri dish (Brives 2010); advertising is like a lab bench; agencies are ‘laboratories’ where ‘desires’ are cultivated (Hennion and Méadel 1993). More specifically, in the case that interests us, this cultivation consists in immersing those receiving the message in one of those good old stimulus-response-reinforcement loops so dear to historical behaviourism – loops that Daniel Berlyne, a behaviourist specialising in curiosity (Berlyne 1950; 1960), presented as essential drivers of this motive:

We have therefore arrived at the hypothesis that curiosity is aroused in a subject when a question is put to him, whether by himself or by an external agent. Some component (SmD) of the response-produced stimulation resulting from the meaning of the question (rm) is assumed to act as a drive-stimulus. And we can see that the intensity of this drive-stimulus, which will in turn depend on the amplitude of the response (rmH) that produces it, will be one of the most important variables affecting the drive strength of the curiosity (Berlyne 1954: 184).

What else do Myriam’s successive promises do, other than to activate an alternation between the stimuli of the questions and the responses of the subject, which Berlyne seeks to describe in purest Pavlovian-Skinnerian style?18 From Bluebeard to Berlyne, from Berlyne to Myriam, the process is always the same: being proposed a series of enigmatic stimuli (doors, questions, promises), being enticed into anticipating a response, and the latter’s encouragement through instances of confirmation (riches, the solution, the promised body part), so that after each stimulus and each correct answer, the desire to give into giddy curiosity is heightened. It is no coincidence that the B-A BA of behaviourism remains just as relevant and powerful in the contemporary world of advertising (Menon and Soman 2002; Hung 2001), despite the disciplinary tradition having long fallen into academic disuse (Péninou 2003). It might be noted, in passing, that the same can be said of functionalism. Are there not many of us who have experienced this? The contemporary sociologist, who, through inattention, allows a ‘function’ to slip into a sentence or line of reasoning, will soon be called to order by colleagues who will inform him or her about the costs of being caught in an act of analytical weakness.19 The police charged with hunting down outbursts of functionalism are now an integral part of the institutions many people deem necessary for the exercise of proper sociological professionalism. However, the very functions suppressed by the social sciences continue to obsess those on the ground: the engineers, traders, politicians, and above all, consumers, who want things to ‘work’, who want to fulfil their ‘role’, to serve a ‘purpose’, and who, despite function being considered a dirty word by specialists of the social, achieve this rather well. The same applies to advertising, whose manifest function is to sell and whose latent function is, as we saw, to test social norms. The world is full of behaviours and behaviouralities, and of functions and functionalities; since sociologists buried Pavlov and Parson, the world has never been as functionalist and behaviourist (I will come back to this). We are thus witnessing an astonishing over-performativity within markets of certain social sciences that continue to ‘operate’, even after becoming silent (or having been ‘silenced’).

At this point in my investigation, although I have carefully outlined some of the forces that inform the campaign, I have not yet broached that which is essential, the most important and the most profound. Was it the erotic charge of the posters that struck – seduced? shocked? – everyone from the outset? Yes and no. Certainly, the campaign’s erotic dimension is as significant and powerful as it is evident, given that the series of posters, far from simply representing a woman’s body, multiplies it and sets in it motion through a striptease and by gradually increasing the stimulation of the senses. In this respect at least, no one would judge the campaign as being unremarkable or even disappointing, even while it is somewhat ‘easy’, demagogical, and vulgar – indeed, inappropriate. The tendency to play on the metonymy of desires, to display a body in order to sell a product, and to hook a consumer by leading a detour via the emotions, has for a long time been one of the most basic forms of market seduction. The use of sexist representations, including the commercialisation of ‘pretty girls’ in a sales pitch, is now generally considered to be the most basic form of advertising.

Moreover, it is not that clear-cut whether or not the campaign does succeed in approaching the very limit of acceptability without tipping over into the scandalous. As Aymeric Mantoux reminds us in his fascinating column on the history of this advert, the collective emotion generated by the promises of the Myriam campaign was not limited to incredulous curiosity when confronted with the degree of audacity outlined above; among some people it also caused fierce indignation. In Lille, the association Du côté des femmes (On the Side of Women) filed an injunction for ‘gross indecency’, calling it ‘a violation of the dignity of women’ and ‘an incitement to voyeurism’. On 5 September, the Lille court responded favourably to the complaint. In accordance with Articles 283 to 290 of the former Penal Code relating to ‘gross indecency committed in particular through the press and books’, the court ordered the billboard company to ‘partially or totally’ conceal the visible posterior (despite the injunction, it was clearly too late to deal with the breasts as Tartuffe once had, given both the changes in traditions and date!). In Paris, the association Choisir (Choose), led at the time by the socialist Member of Parliament, Gisèle Halimi (involved in advocating for women’s rights), attempted to bring the matter before the National Assembly in order to have an anti-sexist law passed. Finally, Yvette Roudy, the then socialist Minister for the Rights of Women, intervened in the press against what she believed to be an exploitation of the female body and a violation of women’s dignity (Mantoux 2010).

That said, in hindsight, and despite the censors, it appears that Myriam worked more to legitimise than suppress the unashamed commercial representation of female models; alongside the prominent political campaign featuring Mitterrand’s ‘quiet strength’ that appeared a few months earlier, it might even have contributed to turning the French into ad-lovers (Maillet 2010). As Jean-Claude Kaufmann clearly highlighted, the campaign’s primary characteristic is its indomitable ambiguity:

What is one to make of […] Myriam, who in 1981 appeared throughout France, taking off the top before promising the bottom? Feminist movements rose up, believing they had detected the image of a woman in her traditional role as sex object […]. The people interviewed for a survey focused more on the trivialisation of female nudity. The campaign’s success came specifically from the ambiguity (Kaufmann 1998: 60).

Here we find a Durkheimian schema but also its counterpart. In the same way that, in Durkheim, the deviant’s behaviour both underlines and questions a shared norm in preparation for future developments (Durkheim 1986), Myriam’s audacity tests public morals and their potential shifts. However, one must not forget that addressing a shared norm and testing a collective conscience inevitably means there is an effect on those who differ from it, ranging from criminals to paragons of virtue. By appealing to an ‘average’ public sensibility, Myriam could only either enthuse or shock those on either side of this general sensibility: a sexist public, advert lovers, those with an interest in humour or sensuality on one side, and, on the other, adherents to specific religious views, the very prudish, or defenders of the status of women. The scandal was therefore inevitable, but it is also important to note its limited and clearly defined scope and a resulting disapproval which was thus far from general. Myriam’s immodesty is at once passé and persistent and this makes it possible to say that, despite a specific sentence being passed, confined to a particular local context, this campaign managed to go as far as it could in search of a limit, without reaching a breaking point and the risk of public opinion turning against it. This is underscored by the designer of the poster:

We would not have been able to do this campaign five years earlier. At that time we were both at the apogee of feminist movements and in a period of calm: there had finally been a de-escalation, a reconciliation of women with their bodies, with the idea of seduction (Pierre Berville, quoted in Mantoux 2010).

Moreover, ever since Myriam, the advertising industry has continued to use female models, sometimes in far more outrageous ways than in Myriam (Parasie 2010; Heilbrunn 2002). Recently, the French internet service provider Alice even took to the extreme the tried and tested method of associating a product and a female figure, unafraid of completely identifying its brand with the image of a ravishing blonde. However, Alice’s competitor, Neuf Cegetel, immediately ridiculed this approach in a caustic TV advert in which we see two advertising executives arguing with one another during a telephone call about what strategy to use when selling their product. The camera films one of them in his living room, in front of a bay window, with a beach in the background:

— Martin? I’ve read the draft for the Neuf Box ad… What’s with the horse? – Well, you have to make people dream, a beach, a beautiful chick… add a small, fat logo in the corner and you’ve got it… [A blonde in a bikini on horseback crosses the beach in the background] – Yes, but the subject is unlimited calls in France and in 30 other countries. – If that’s the only problem we’ll give her a phone [The same blonde on horseback passes in the background, this time with a phone glued to her ear] – Yeah… – Then, we add comedy… [The blonde in the frame of the bay window falls off the horse] People like comedy… [The offer’s conditions are overlaid and scroll past] – Hey Martin, this ad has got to say that it’s all in the Neuf Box, as well as unlimited calls, all for less than thirty Euros… – Well, that’s what’s written, we even tell people to go to neuf.fr – And we have to show a blonde for that? – Do you prefer brunettes?20

Connoisseurs will have noticed in passing the highly exaggerated (subconscious?) homage to the skilled scenography of Myriam, with the beach, the bikini, the three appearances – the addition of an accessory (the phone) replacing the subtraction of another (the bikini top) – and the final punchline when the model falls (‘this time, I’m removing Alice!’), not forgetting the reflexive reference to the work of advertising, using teasing (the logo ‘N9UF’, that reveals the identity of the advertiser, is not visible at the start of the clip) and the affectionate wink in the direction of a historical preference for brunettes.21 However, this homage to a golden age of advertising know-how that has perhaps passed, achieved on the back of Alice,22 does not wholly do justice to the genius of Myriam, as the latter goes well beyond using the female body for the purposes of marketing. Myriam – by taking excitement and curiosity to their limit, by playing with the three forms of promise, the desire to know, and the revelation of something intimate – does not simply limit itself to the clever use of commercial sexism. It also establishes a highly particular link to the anthropological foundations of curiosity. What is most important therefore lies beyond the body game. In order to demonstrate this, I would like this time to echo the ‘how far can we go’ approach by attempting a rather scandalous exegesis that I am only risking as it is well suited to an advert which, after all, adopted this approach. As we shall see, Myriam echoes the intellectual and sexual burden of Genesis (whose components it mimics), but of course to show them differently, and for an entirely different purpose.

Fig. 10. Neuf Ad: Do you Prefer Brunettes?

Firstly, Myriam operates a double reversal of the sacred story (and therefore of its profane version, Bluebeard). In the Bible, as in the tale, keeping one’s promises and being curious are completely contradictory: in the Garden of Eden, as in Bluebeard, breaking one’s promise is harshly punished. Conversely, with Myriam, curiosity is needed for the promises to be fulfilled. Furthermore, it leads to them being kept: contrary to Eve and Bluebeard’s wife, Myriam fulfils her commitments, twice over. On the one hand, she maintains the consumer’s involvement in the game; on the other, she honours the advertiser’s word. Every time, the promise that an item of clothing will disappear is scrupulously fulfilled. The second reversal concerns Genesis more specifically.

The excitement of curiosity is a sin connected to the Fall; striptease and curiosity are inseparable. In Genesis, the ‘strip’ (the sequence) involves dressing: the move is from a state of innocent nudity to an awareness of modesty, as Saint Augustine also noted:

Augustine adds a detail […].23 In summary, he claims that Adam and Eve did not just become aware that they were naked but also noticed that lust, about which they knew nothing before the sin, provoked a certain stirring in their bodies. And it was precisely because of this that, albeit too late, they quickly prepared a cache-sexe (From civ. Dei, XIV, 17). However, when this ‘rebellion of the flesh’ occurred, before the concealment of their modesty, that is, Adam and Eve (continues Augustine imperturbably) began to look at their own respectively shameful parts curiosius (XIII, 24, 7). And in this curiosius is a mixture of heightened attention (let us not forget the comparative dimension) and dawning embarrassment, and even, in the persistence of the gaze, and before modesty comes into play, brazen shamelessness. […] after the fall of Adam and Eve and, more specifically, as soon as they look curiosius at each other’s nudity, the life of man on earth would become one of continuous temptation. In sum, man would always have a natural penchant for curiositas (Conf, XIII, 20–28) (Tasitano 1989: 31–32).

What Maria Tasitano is saying (and in particular what Saint Augustine says through her) warrants attention because this argument reminds us that the vine leaves are there to cover the birth of modesty, the awakening of lust, and the guilt inherent to the loss of original innocence. In the Garden of Eden, the curiosity aroused by the forbidden fruit leads to another curiosity, this time spontaneous, concerning bodies. We are therefore better able to understand the reversal operative in Myriam as well as its formidable, yet troubling, ambiguity. On the one hand, her striptease is scandalous because it moves in the opposite direction to Genesis. By activating a curiosity regarding the hidden body, the undressing of Myriam ruins the effort made by Adam and Eve to minimise the consequences of their Fall; it once again exposes the now shameful parts they were trying to conceal. From this perspective, the campaign lies on the side of sin and it is possible to understand how it would have generated criticism. However, from another point of view, it is equally possible to interpret Myriam’s striptease as a backwards movement. It is as if, by lasciviously removing one by one the fig leaves used by our ancestors, after a fashion, to counteract their guilty sexual curiosity, we were – rather than exacerbating the Fall and its disastrous consequences – rewinding the film of Genesis step by step so as to return to the state of original innocent nudity, to a time before the Fall when Adam and Eve were naked,24 when they kept their promises, just like the (still to come) Avenir poster, and when they were not aware of their sensuality,25 as suggested by its creators:

[The controversy] was a heresy. Myriam was a pure product of 1968, she had a perfectly healthy relationship with her body, with nature, a completely guilt-free relationship with nudity (Comments made by Pierre Berville, poster designer, quoted in Mantoux 2010; my italics).

According to this point of view, there was a lucky, innocent coincidence: because two scheduled professional models failed to show up a few days before a photography session that had been organised in the Bahamas, the photographer Jean-François Jonvelle (who specialised, admittedly, in glamour photography!26) suggested one of his friends to the agency, whose real name was actually Myriam. Myriam was therefore not a professional model but an ordinary person, without a tiny waist or overly pronounced features; ‘natural’, in other words, far removed from the oneiric-artificial creatures that tend to populate the world of advertising:

I had quite a natural look and I also had a very natural relationship with my body, and he didn’t want to get too into the female vamp, the enticing woman, that wasn’t really the idea and I think they wanted someone fresh […] Funnily enough, I was 19 at the time and I refused Playboy and that kind of thing but being naked didn’t bother me, in the context a nudity that was natural I was completely at ease. But I had never wanted to associate myself with an image that could be considered even slightly sexual. I didn’t want to do that but the poster was clear because I had seen the drawings, it was…well, I thought it was a good idea… Of course, no one knew that it would be so successful, not me or anyone […] A year later I went on a retreat in a forest, no one saw me any more. [It wasn’t because of the campaign]. When the campaign had so many repercussions I wasn’t really that concerned. I had done it just to earn a bit of money, to pay my rent while I was away, so I wanted to pay for my rent in Paris whilst I was on that retreat. So that is what the campaign did and that was the only purpose of my job as a model, I didn’t want to make a career out of it (Author’s interview with Myriam).

Reading the Avenir poster in this way also means returning to the difficulties within Bluebeard, this tale torn between a moral that is both repressive and permissive, marking the transition between a sacred curiosity (suppressed completely) and a market curiosity (often encouraged). Both of these morals are as entrenched in the posters as they are in the collective subconscious: the ambiguity of Myriam works both through the ever-present discourse of Scripture, in simultaneously referencing the original innocence and the feeling of guilt, and through advertising culture, in oscillating between condemning the commercialisation of the female form and variously accepting it in the name of the candour of humour, a certain emancipation, and a new language (Parasie 2010). On the one hand, just as Jupiter adopted the appearance of Amphitrion to seduce Alcmena, the advertiser borrows Myriam’s body and voice to capture its audience. On the other hand, the discourse of Myriam particularly mischievously revives the two inseparable sides of virtue: the promises made, and the primitive innocence of the undressed body. These virtuous elements are emphasised through the extreme simplicity and starkness of its presentation. ‘Thanks to the naked Eve (‘Ève nue’) coming (‘à venir’: forthcoming) soon, Avenir has arrived (‘est venu’ or, literally, ‘has come’). This subtle pun (in French at least!), at once involuntary and somewhat juvenile, at least has the advantage of folding into a spectacular chiasmus; the entire anthropological background that, whether we like it or not, informs the story.

Box 3. Volvo’s Tentation (temptation) Offers

For those not satisfied with the mirror-image inverted stripteases of Myriam and Genesis, and for those who still doubt the underlying links between advertising teasing and Biblical temptation (because they observe either, at best, the hare-brained ideas of an analyst blinded by his subject or, at worst, a sacrilegious comparison), it is worth taking a detour via the following leaflet by the carmaker Volvo:

.jpg)

Fig. 11. Volvo Tentation Offers

This leaflet (almost! See insert 3 below) brings full circle my own stripping of the layers of the history and forces of teasing, given that it manages to draw together across three pages the highly carnal strip-tease-removal of the Kellogg’s example, the triple teasing of Myriam (hooking, unveiling, revelation), and the symbolism of Genesis,27 including the apple, temptation, and not forgetting the fig leaf that discreetly features in the bottom left-hand corner of the far left panel; and, of course, the Fall (‘choose… succumb’ – ‘choisissez… succombez’).28

Of course, the mobilisation of myth is a means for Myriam, not an end. The advert’s anthropological background is directed entirely towards the pragmatic efficacy that is disclosed in the final revelation: ‘Avenir, the billboard company that keeps its promises’. Just as with modern packaging, part of the surprise is, to some extent at least, the lack of surprise, given that the bikini bottom has clearly been removed and the body exposed, despite the model rotating 180°. The ‘reveal’ (from the waist down), seen ‘from behind’ and thus far more acceptable than representing the pubis that is either expected or dreaded – the ‘front’ view – as well as the surprise revelation of the message’s meaning – which consists of promoting, with dizzying reflexivity, the dependability and know-how of advertising professionals – are an occasion for a moment of clarification, for relaxation, and even mutual communion, taking the form of an implicit dialogue between the partners of the exchange: the amused ‘admit that you did not guess the point and that I really scared you!’ by the advertiser is followed by the ‘ah, that’s what it was all about then; I get it now’, which is undoubtedly experienced by the majority of passers-by through registers of admiration, complicity, and relief (tainted for some by slight disappointment or, for others, frank indignation?), through a knowing smile at the corner of their mouths (or pursed lips). The promise was kept perfectly in return for a little moral hazard,29 subtly played on the side of virtue: given that the advertiser scrupulously maintained the model’s initial pose and accomplished the removal of the bottom item of clothing, it was in fact justified, in order to keep its promise, in making the most of the absence of any prior commitment about the viewing angle, at the cost of a whiff of scandal but without risking an outcry. Above all, this final ‘pirouette’, in the true sense of the word, gives the advertiser the opportunity to share with its public Myriam’s point of view, to look with her – and if possible, with it – towards the horizon of advertising territories yet to be conquered.

The structure Pn-1* + Pn continues at least to rank 3, while secretly hoping to retain its validity until rank n, to infinity. Keeping the promise P2 is accompanied by a new promise, P3. Although implicit, the latter is paradoxically the most well understood, the most important, and the most significant of the three, given that the entire campaign is directed towards its performative potential: ‘from this point and from now on “it’s going to be mind-blowing”: if you hire me, I promise to remove all the obstacles you would never have thought able to remove from your path; I will grant your wildest wishes’. Roland Canu (2011b) demonstrated magnificently the extent to which the effectiveness of advertising relies perhaps less on the mysterious power we assign to it than on ploys similar to those employed by the Wizard of Oz, the legendary character who succeeded in making all his companions’ wishes come true by using what were in fact, quite prosaic forms of subterfuge. Avenir’s advertising campaign uses at least four tricks of this kind.

The first involves linguistic confusion. Normally, ‘keeping your promises’ means ‘realising announced objectives’. With Myriam, this ordinary meaning is put forward, while the promise’s actual meaning is more literal, or even literary, given that it limits its respect for commitments to the linguistic scope of the statement: we say what we will do and will do what we say, but we only say and do so in within the closely circumscribed area of the billboard – to the exclusion of everywhere else. In doing so, the campaign undertakes a double substitution of the forms of effectiveness we ascribe to advertising media. On the one hand, the (discursive) fulfilment of a sequence of (still discursive) promises is presented as an (illusory) demonstration of a desired commercial effectiveness; on the other, getting yourself talked about is offered as (false) proof of commercial power, given the distance between notoriety and actual sales.

The Wizard of Oz’s second trick involves a ‘public illusion’, to paraphrase the title and spirit of the famous play by Corneille. In the play, Clindor captivates his father Pridamant by making him believe, thanks to a magician’s tricks, that he was now able to view the life of his son, who he believed had disappeared. In fact, Clindor and his accomplices are themselves acting out his life before Pridamant to convince him of the power of theatre and the nobleness of the acting profession they had embraced. Similarly, Myriam organises a spectacle for the captation of the general public so as to captivate the captors. Now, this strategy reminds us of the conclusion to the second of the morals in Bluebeard: ‘No husband of our age would be so terrible as to demand the impossible of his wife, even if he be such a jealous malcontent; he is meek and mild with his wife. For, whatever the colour of her husband’s beard, the wife of today will let him know who the master is’. Perrault did not know how true that was: with Myriam, it is as if a thousand curious wives had already been recruited to demonstrate to contemporary Bluebeards30 – who now go by the names of Big Blue, Racing Green, the Yellow Pages, Orange, Red Bull, among others! – their ancestor’s system, in order to sell them both the rooms and the keys, to the extent that they are made to fall, quite literally, into a trap of their own making. In so doing, they also validate the irony of behaviourism, according to which the effectiveness of conditioning can be greater for the conditioner than for those being conditioned (with the notable exception, as we shall see, of the conditioner of the conditioners):

In a wealthy economy in which consumers have great latitude of action, suggestion plays a role. There is also manipulation. But who manipulates whom? There can be no doubt that the consumer also manipulates the advertiser, the retailer, and the manufacturer, who all carefully watch for any slight change in consumer tastes and buying inclinations. The often told story of the animal psychologist who spent years training his rats to respond to various stimuli only to realize ultimately his rats regulated his life contains a grain of truth. Among consumer and advertiser, as in all interpersonal relationships, there is interaction (Katona 1960: 242).

However, there is something even more subtle going on. The Wizard of Oz’s third trick consists in initiating and then coming back to a game of masks. The Myriam campaign is not simply any old campaign for any old product. It is indeed an advert, but above all it is an advert about and for advertising. As such, the series of posters possesses a dizzyingly reflexive power: it appears both as a masterful exercise in advertising and as a skilful theorisation of the same; it explores how far it can push its own logic; it theorises and spells out a way of acting whilst simultaneously putting to the test its own exploration and modus operandi. To use a form dear to Roland Barthes,31 the Avenir advert adopts a ‘Larvatus Prodeo’ approach: it wears a mask as it proceeds, adopting Myriam’s features while at the same time (almost) pointing to the mask. The message is: ‘experience the power of the mask and discover the force behind this power’. In fact, if we look closely, the last item of clothing to be removed in the poster is less the bikini bottom than Myriam’s body itself, so as to reveal, through the use of contrast, the entire power of the clothing of advertising in which she has been dressed from beginning to end. In Myriam, the Wizard of Oz is no longer discovered by accident; on the contrary, it is as if the wizard intended to take advantage of the public exposure of his trick, by demonstrating it to be more extraordinary and powerful than the magic it is intended to simulate.

But who is the wizard here? Who is hiding behind the mask of Myriam? Avenir, of course: in the end, it is all too obvious to expose the identity of the campaign’s beneficiary. However, is there not someone else, someone hiding behind Avenir? To answer the question positively means pointing to the last mask, and the fourth and most astonishing magician’s trick. This trick consists in playing with the eminently likely confusion in the mind of the general public between ‘billboard company’ and ‘poster designer’, between services responsible for dealing with the urban logistics of the various messages (managing billboards and putting up posters) and advertising agencies. Just as in Genesis, the ‘work of temptation’ is shared between the Creator, who designs the Garden of Eden, and the snake, who draws attention to the forbidden fruit; in the world of commercial communication the task of arousing market curiosity is split between those who respectively create and display advertising. Avenir falls into the second category: it is a ‘billboard company’ that was bought in 1999 by the street furniture company J.C. Decaux, but whose identity and name was retained, no doubt due to the brand’s reputation ever since Myriam and, of course, thanks to her. However, Avenir is closely linked to another actor, from the first category of advertising specialists: behind Avenir’s mask, and also hiding in the Myriam posters, was the agency CLM/BBDO, of whom the billboard company was but a client. This is what is so extraordinary: the advertising magician does not just have one understudy, but two; CLM/BBDO is wearing the mask of Avenir… who is wearing the mask of Myriam.

This set of masks, whose layering redoubles the removal of layers of clothing, plays on an intoxicating ambiguity that, as we shall see, echoes the forked moral of Bluebeard, but which first and foremost involves the two-sided public addressed by advertising. Advertising is directed at two targets: on the one hand, it is presented to the public; on the other, it is sold or bought by professionals – the press and advertisers, respectively (Chessel 1999).32 So far, I have adopted the public’s point of view: I read the series of posters through the eyes of the everyman – in other words, employing only the skills and knowledge of someone whose eyes landed one day on the Myriam poster series. However, if I switch position and adopt the point of view of advertising professionals, the same campaign takes on a completely different meaning, in a kind of final dramatic twist accessible only to those with the necessary expertise to understand the real hidden agenda, as it were:

There was no intention or desire to shock at all. We wanted to provoke people’s awareness. The brief delivered to the agency by Avenir’s CEO involved a business to business problem: at the time, billboard advertising was not considered to be a reliable media outlet given that posting dates could not be guaranteed. It was difficult to promote. Avenir was the first to develop a system to guarantee posting dates. In order to demonstrate this, we naturally suggested they prove it through billboards, by providing regular deadlines! (Comments by Pierre Berville, quoted in Mantoux 2010).

This was therefore Myriam’s real mission. Behind the double promise to undress – made to the public – lay another double commitment – this time made to its sponsor – involving the tempo of the striptease. Myriam’s mandate (the brief delivered to the agency by the chairman of Avenir) was to act as a promotion that would prove Avenir’s reliability as a billboard company. From this point of view, the performativity of the message is not only self-referential, as I mentioned earlier, but also involves a ‘performance’ that is well and truly material, that is to say indexed to the real world, given that everyone was able to compare the poster’s promises to the actual public calendar. On the other hand, what is shown is a pretext that does not refer to anything real except to its time of exposure: Myriam’s body is phatic; it is only there to say there is nothing to sell or convey except for a coded message aimed at professionals. The real promises kept are in fact less concerned with bodily revelation than with respecting the dates and intervals that ensure the scansion! The original, professional meaning of the messages is in fact as follows: