Mattering Press

Mattering Press is an academic-led Open Access publisher that operates on a not-for-profit basis as a UK registered charity. It is committed to developing new publishing models that can widen the constituency of academic knowledge and provide authors with significant levels of support and feedback. All books are available to download for free or to purchase as hard copies. More at matteringpress.org.

The Press’s work has been supported by: Centre for Invention and Social Process (Goldsmiths, University of London), Centre for Mobilities Research (Lancaster University), European Association for the Study of Science and Technology, Hybrid Publishing Lab, infostreams, Institute for Social Futures (Lancaster University), Open Humanities Press, and Tetragon.

Making this book

Mattering Press is keen to render more visible the unseen processes that go into the production of books. We would like to thank Joe Deville, who acted as the Press’s coordinating editor for this book, Jenn Tomomitsu for the copy-editing, Tetragon for the production and typesetting, Sarah Terry for the proofreading, and Ed Akerboom at infostreams for the website design.

Cover

Mattering Press thanks Łukasz Dziedzic for Lato, our incomparable cover typeface. It remains one of the best free typefaces available and is released by his foundry tyPoland under the free, libre and open source Open Font License.

Cover art by Julien McHardy.

Originally published as De la curiosité: L’art de la séduction marchande © Armand Colin, 2011.

This translation © Franck Cochoy, 2016. First published by Mattering Press, Manchester.

Cover art © Julien McHardy, 2016.

Text design, typesetting and eBook by Tetragon, London

Freely available online at www.matteringpress.org/books/on-curiosity

The conditions of the licence agreed with the original publisher mean that Mattering Press cannot grant permission to reprint or reproduce this translation by any electronic, mechanical, or other means. Permission requests can be sent to the publisher at editors@matteringpress.org.

The cover art is licensed under a Creative Commons By Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike licence. Under this licence, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy their work so long as the material is not used for commercial purposes and the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar licence. No permission is required from the authors or the publisher. Statutory fair use and other rights are in no way affected by the above.

Read more about the licence at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

ISBN: 978-0-9955277-0-6 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-0-9955277-1-3 (ebk)

Mattering Press has made every effort to contact copyright holders and will be glad to rectify, in future editions, any errors or omissions brought to our notice.

Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Teaser

- 1 · From Eve to Bluebeard: The Difficult Secularisation of Curiosity

- 2 · Bluebeard: Towards the Marketisation of Curiosity

- 3 · ‘Peep Shop’? An Anthropology of Window Displays

- The Effects of Locks

- The Effects of Mirrors

- 4 · ‘Teasing’

- Packaging (Teasing, Scene 1)

- Advertising (Teaser, Scene 2)

- Continually Agitating Curiosity, or How to Lead a Consumer towards Wonderland

- Data Matrix

- 5 · ‘Closer’

- Door-closer

- Closer

- Appendix · Bluebeard

- Notes

- Bibliography

List of Figures

Illustrations

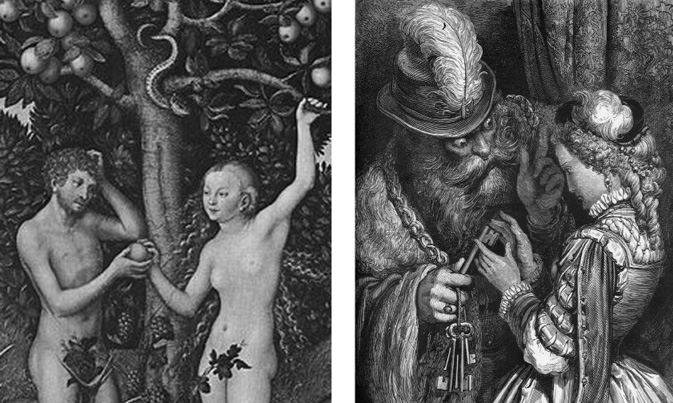

- Fig. 1 Lucas Cranach the Elder and Gustave Doré

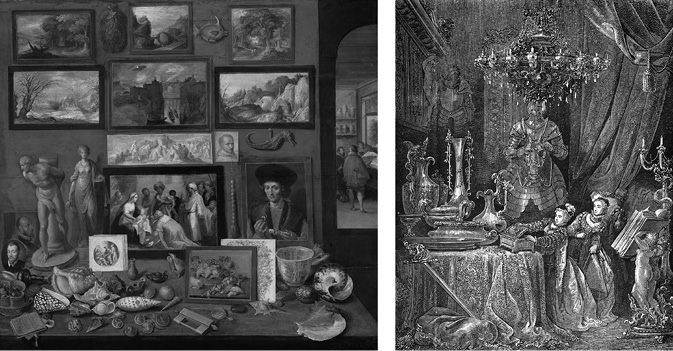

- Fig. 2 Frans Francken II; Gustave Doré

- Fig. 3 The Progressive Grocer, February 1940, p. 127

- Fig. 4 The Progressive Grocer, February 1940, p. 59

- Fig. 5 The Progressive Grocer, February 1940, p. 58

- Fig. 6 Monsieur Plus, Bahlsen

- Fig. 7 The Progressive Grocer, December 1957, p. 38 (detail)

- Fig. 8 The Progressive Grocer, December 1957, pp. 35–40

- Fig. 9 Avenir, the Billboard Company that Keeps its Promises

- Fig. 10 Neuf Ad: Do you Prefer Brunettes?

- Fig. 11 Volvo Tentation Offers

- Fig. 12 Daily Mail, 30 April 1914 (quoted in Field, 1959)

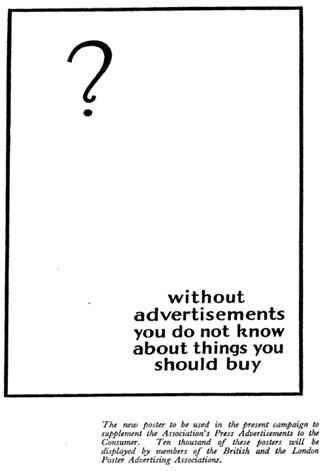

- Fig. 13 Advertising Association Campaign, 1936

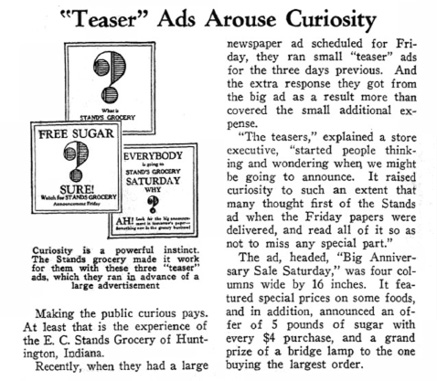

- Fig. 14 The Progressive Grocer, September 1929, p. 56

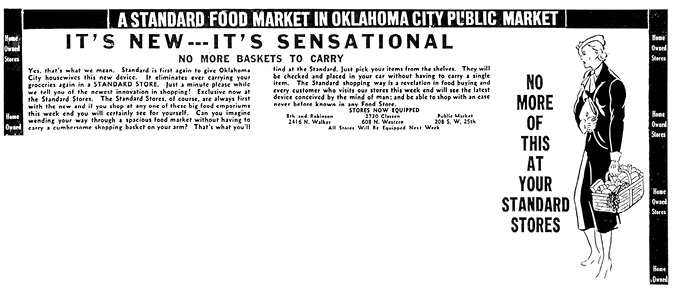

- Fig. 15 No More of This at Your Standard Stores (Wilson 1978)

- Fig. 16 Fnac, Curiosity Agitator (v. 1)

- Fig. 17 Data Matrix

- Fig. 18 Door-closer (Nantes, August 2010)

- Fig. 19 The Progressive Grocer, The magic door, February 1951, p. 201

- Fig. 20 The Progressive Grocer, August 1940, pp. 76–77

- Fig. 21 Mediapart, 16 June 2010, ‘The Stolen Secrets of the Bettencourt Affair’

- Fig. 22 Le Figaro.fr and Le Figaro: Are you in favour

of the total ban on the burqa? (22 and 23 April 2010) - Fig. 23 Making Things Public, ZKM

- Fig. 24 LeMonde.fr and CoveritLive, 1 July 2011

- Fig. 25 Closer, no.266, 17–23 July 2010

Boxes

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to all those who contributed significantly to the writing of this book, through their assistance, their support, their contributions, their suggestions, their proofreading, the documents they passed on to me or suggested, and/or the opportunities they gave me to test my arguments during different symposiums and seminars:

Luis Araujo, Nicolas Auray, Vincent Berry, Alexandra Bidet, Anni Borzeix, Emmanuel Boutet, Arlette Bouzon, Florence Brachet-Champsaur, Roland Canu, Johann Chaulet, Nathalie Cochoy, François Cooren, Marlène Coulomb, Frédéric Couret, Barbara Czarniawska, Caroline Datchary, François Dubet, Sophie Dubuisson-Quellier, Paul Du Gay, Marie-Anne Dujarier, Patrick Fridenson, Danielle Galliano, Martin Giraudeau, Mathieu Gousse, Johan Hagberg, Benoît Heilbrunn, Jean-Claude Kaufmann, Emmanuel Kessous, Martin Kornberger, Aurélie Lachèze, Michèle Lalanne, Raphaël Lefeuvre, Claire Leymonerie, Celia Lury, Christian Licoppe, Alexandre Mallard, Liz McFall, Catherine Paradeise, Guillaume Queruel, Stefan Schwartzkopf, François de Singly, Jan Smolinski, Laurent Thévenot, Valérie Inès de la Ville, Lars Walter, and Steve Woolgar.

I feel immensely indebted towards Jaciara Topley Lira and Joe Deville for their amazing work on the translation. Thank you so much, Joe, for your encouragement to publish this book in English at Mattering Press, and for working so hard to have it even better than the original version!

More generally, I am very grateful to all those whose works nourished and inspired me: with a special thanks to Michel Callon and Bruno Latour.

I also owe a great deal to the colleagues and institutions which generously supported my work: all of the partners from the Œnotrace project, CERTOP, my laboratory, and the sociology department at the University of Toulouse II in France; the Center For Retailing, the Center for Consumer Science and Handels, the School of Business, Economics and Law of the University of Göteborg in Sweden. These last three institutions welcomed me as Visiting Professor from 2009 to 2013 and provided me with the ideal conditions for writing this book. Nor can I forget the support given to me by the Education Abroad Program and the National Research Library Facility at University of California, Berkeley, to which I owe some of the essential data on which my work is based.

And finally, my gratitude goes to the natural and legal persons who allowed me to reproduce some of the illustrations included in this book (those being, and in order of appearance): the Samuel Courtauld Trust and the Courtauld Gallery in London for Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Adam and Eve; the Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna for Frans Francken the Younger’s Cabinet of Curiosities; the Progressive Grocer magazine for all the images I borrowed from that publication; the Saint-Michel biscuit factories for the Bahlsen advert; Claire Jonvelle and Myriam Szabo for the Myriam advert, produced by the CLM-BBDO agency; SFR for the Neuf Telecom advert; Volvo Cars for the leaflet on ‘Offres Tentation Volvo’, produced by the Unedite agency; the History of Advertising Fund for the English Advertising Association campaign; FNAC as an agitator of curiosity for the FNAC advertising spot; the journal Mediapart for its headline from 16 June 2010.

Of course, the statements expressed herein are mine alone.

Teaser

In many respects, this book might derail some readers. All those who prefer to know what to expect, to reason on the basis of well-established analytical frameworks and not to risk wasting their time on uncertain ramblings, are thus strongly advised to go on their way.

Seducing an audience – attracting the attention of a reader, catching a client’s attention, converting a non-believer, responding to a user’s expectations, persuading a voter, etc. – often involves building technical devices which play on people’s social dispositions. The excerpt above is one such device (the irony!): it is a small, rhetorical machine which attempts to play on the reader’s disposition towards conservatism and/or exploration. And there are many others, especially within marketing settings, which will be my field of choice here. For example, in order to attract customers, we can use a slogan promoting their penchant for repeating a habit (‘Nutella, spreading happiness every day’); suggest a loyalty card which employs calculative capacities so as to better tie them to a future routine (‘5% discount on the brand’s products for cardholders’); propose a brand which appeals to a propensity for altruism (‘Max Havelaar: great coffee [for] a great cause’); and so on. In other words, each one of these little machines for equipping the relationship between an organisation and its audience ascribes an attitude to people, in both senses of the word: they assume that the intended targets already behave according to this or that logic, and/or supply them with a possible mode of action; they suggest a way of behaving which this or that person did not necessarily have in mind (as something inbuilt/as a possible idea) but in which they can recognise themselves or which is likely to catch their attention. With captation1 devices, the opposition between human and non-human entities disappears, as does that between their supposed privileges and respective ‘ontologies’, given that artefacts play a key role in defining or activating motives for action (and vice versa).

I would like here to explore the dynamics of these devices and dispositions, by focusing on a particular disposition in greater depth – curiosity – and on the particular devices which allow it to be expressed and spread throughout society. Why curiosity? In my view, it would be better to answer this by asking the opposite and even more intriguing question on which it is grounded: why not curiosity? Why should it be curious to experience curiosity about curiosity? This book is the fruit of a twin astonishment: on the one hand, twenty years of observing commercial scenes convinced me that of the dispositions activated by marketing devices, curiosity features prominently as a force behind everyday action; and on the other, this finding only makes it more surprising that this banal disposition is almost completely absent from the current sociological lexicon, or at least it was until very recently.2 Classical sociology, it seems, prefers conservative modes of action, first and foremost habit, which curiosity, however – with the support of a related but equally neglected disposition: boredom – calls into question. Curiosity leads us to move beyond ourselves, and thus helps us to finally experience a little boredom, or perhaps more precisely weariness, about this ‘habit’ we know so (too?) well; and to be curious about this curiosity (which, if not newer, is at least unusual) which calls habit into question. I am willing to wager that curiosity can help us understand how market professionals and technologies, and more generally all specialists in interpersonal relations, are able to reinvent a person’s identity and their mobility.3 They do this by playing on people’s inner motivations, in the hope of being better able both to draw these people toward them and to make them act according to their wishes.

I propose to conduct this exploration of curiosity by starting with an analysis of Bluebeard, the fairy tale written by Charles Perrault, given that this story is itself a pure curiosity machine which operates at the intersection (as we shall see) of mythical history and the contemporary anthropology of this particular disposition. The fact that exploring curiosity leads me to take a detour via popular culture – as well as religion, literature, literary criticism, history, philosophy, economics, psychology, management, and others – instead of sociology, which is my primary discipline, merely illustrates the necessity that confronts the sociologist who deals with curiosity, of drawing on sources other than those from his own discipline. It also illustrates the refreshing and potentially fertile nature of an exercise which consists in using the object being considered – curiosity, that is – as the means of its own exploration.

As is often the case in stories, in Bluebeard it is what is said at the beginning rather than at the end that matters most. The best way of dealing with this text is to quote the opening directly:

There was once a man who had fine houses, both in town and country, a deal of silver and gold plate, embroidered furniture, and coaches gilded all over with gold. But this man was so unlucky as to have a blue beard, which made him so frightfully ugly that all the women and girls ran away from him.

One of his neighbors, a lady of quality, had two daughters who were perfect beauties. He desired of her one of them in marriage, leaving to her choice which of the two she would bestow on him. Neither of them would have him, and they sent him backwards and forwards from one to the other, not being able to bear the thoughts of marrying a man who had a blue beard. Adding to their disgust and aversion was the fact that he already had been married to several wives, and nobody knew what had become of them.

Bluebeard, to engage their affection, took them, with their mother and three or four ladies of their acquaintance, with other young people of the neighborhood, to one of his country houses, where they stayed a whole week.

The time was filled with parties, hunting, fishing, dancing, mirth, and feasting. Nobody went to bed, but all passed the night in rallying and joking with each other. In short, everything succeeded so well that the youngest daughter began to think that the man’s beard was not so very blue after all, and that he was a mighty civil gentleman.

As soon as they returned home, the marriage was concluded. About a month afterwards, Bluebeard told his wife that he was obliged to take a country journey for six weeks at least, about affairs of very great consequence. He desired her to divert herself in his absence, to send for her friends and acquaintances, to take them into the country, if she pleased, and to make good cheer wherever she was.

‘Here,’ said he, ‘are the keys to the two great wardrobes, wherein I have my best furniture. These are to my silver and gold plate, which is not everyday in use. These open my strongboxes, which hold my money, both gold and silver; these my caskets of jewels. And this is the master key to all my apartments. But as for this little one here, it is the key to the closet at the end of the great hall on the ground floor. Open them all; go into each and every one of them, except that little closet, which I forbid you, and forbid it in such a manner that, if you happen to open it, you may expect my just anger and resentment.’

She promised to observe, very exactly, whatever he had ordered. Then he, after having embraced her, got into his coach and proceeded on his journey.

Her neighbors and good friends did not wait to be sent for by the newly married lady. They were impatient to see all the rich furniture of her house, and had not dared to come while her husband was there, because of his blue beard, which frightened them.4

All French readers (and certainly many people in other countries!) know what happened next:5 along with her friends, seduced by all the things, chests, and other furniture which she had been allowed to see, Bluebeard’s wife inevitably succumbed to the curiosity which drove her to explore, alone, the cabinet which she had promised not to open. There, reflected in a mirror of blood, she discovered the hanging bodies of all the other wives who had preceded her. She was so horrified by the sight that she dropped the key to the floor; this then became marked by a bloodstain, which proved impossible to remove. Returning home, Bluebeard discovered that his wife had not kept her promise, and decided that, like his previous wives, she must die. After begging Bluebeard and shouting for help by desperately calling for her sister (‘Anne, sister Anne, do you see anyone coming?’), the poor woman was fortunate to see her brothers arrive in time to save her and to kill Bluebeard. The inheritance from Bluebeard allowed his surviving wife to remarry and to marry off her sisters, and to buy captains’ commissions for her brothers.

In the arguments that follow, I propose to draw on this tale reflexively. In spite of Bluebeard, but also thanks to him, I intend to be (and to make those of my readers who are not already) curious about curiosity. I will try to find keys and rooms in addition to the small – all things considered! – number that appear in the story of the man with the strange shock of facial hair. As we shall see, there are two other secret rooms in Bluebeard’s house that are yet to be explored. These rooms are neither those more sumptuous ones located upstairs, nor on the ground floor, like the room of horrors; we will nonetheless visit these many rooms carefully (chapter 2). Like the archaeological foundations of the house, the first forgotten room was built well before Bluebeard somewhere in the cellar. This room contains the complete ancient anthropological history of curiosity, and more specifically, the Bible and the cabinets of curiosity that precede, but also modify this early history (chapter 1). The second room was built later and is higher up, in the attic, and is filled with the contemporary uses of curiosity in markets, whether window displays (chapter 3) or ‘teasing’ devices, intended to activate curiosity further and in different ways (chapter 4). By exploring the very smallest nooks in each of the rooms in the story of Bluebeard, I aim to uncover a deeper level through which the tale operates (a transitional space between the two forgotten rooms), as well as to reveal both the anthropological persistence and constant renewal of curiosity which constitutes – as we come to realise by the end of the fairy tale, and occurring today as much as it ever has – one of the principle modes of action capable of changing both people and their worlds.

1

From Eve to Bluebeard: the Difficult Secularisation of Curiosity

It is well known that Perrault’s tales, far from being original, are rather revised literary versions of popular tales, often drawing on oral traditions (Soriano 1977). The tale of Bluebeard follows this model, but in a very particular way. It follows the model insofar as its account of the dangers of curiosity, as in the themes dealt with by many other fairy tales, is far from new. However, things are nevertheless different. The story not only recounts a popular fairy tale,1 but also possibly retells historical events. The models for Bluebeard perhaps include: in France, Gilles de Rais, Joan of Arc’s companion, who murdered a number of children and was hanged and then burned for his crimes and acts of witchcraft (Cazelles and Wells 1999); and, in England, Henry VIII, who executed two of his six wives. We can also say, with even greater certainty, that it retells the ‘tale of tales’: the most obvious source of inspiration (whether direct or indirect) for Bluebeard seems to me to be the Bible and its story of the tree of knowledge and of Eve and the Serpent:

Now the serpent was more crafty than any of the wild animals the Lord God had made. He said to the woman, ‘Did God really say, “You must not eat from any tree in the garden”?’ The woman said to the serpent, ‘We may eat fruit from the trees in the garden’, but God did say, ‘You must not eat fruit from the tree that is in the middle of the garden, and you must not touch it, or you will die’. ‘You will not certainly die’, the serpent said to the woman. ‘For God knows that when you eat from it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil’. When the woman saw that the fruit of the tree was good for food and pleasing to the eye, and also desirable for gaining wisdom, she took some and ate it. She also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate it. Then the eyes of both of them were opened, and they realised they were naked; so they sewed fig leaves together and made coverings for themselves. Then the man and his wife heard the sound of the Lord God as he was walking in the garden in the cool of the day, and they hid from the Lord God among the trees of the garden. But the Lord God called to the man, ‘Where are you?’ He answered, ‘I heard you in the garden, and I was afraid because I was naked; so I hid’. And he said, ‘Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten from the tree that I commanded you not to eat from?’ The man said, ‘The woman you put here with me – she gave me some fruit from the tree, and I ate it’. Then the Lord God said to the woman, ‘What is this you have done?’ The woman said, ‘The serpent deceived me, and I ate’.2

As we know, God then punishes the three protagonists: he condemns the Serpent to crawl and to eat dust, the woman to give birth in pain and to live under the domination of her husband, and Adam to cultivate the soil (and, upon his death) to finally return to it himself.

The analogy between Bluebeard and Genesis is as strong as it is evident: in both stories a mysterious agent (God or man) prohibits a woman from approaching one item amongst many others; that same or another item stimulates her curiosity, pushing her to contravene the initial prohibition, and either punishes her or tries to punish the person (or people) who were unable to keep their promise. In both cases, the force (incentive?) of the temptation is exactly the same: access is granted to all the trees or cabinets, with the exception of one. There are of course very considerable differences between the two stories, which might outweigh their similarities, but before exploring these differences and their meanings, I would like to emphasise the extent of the parallels we can establish between the two.

The story of Bluebeard is nothing more than a profane variation of a very old, mythical story. As such, curiosity defies the sacred: it is a disposition that is deeply linked to an old anthropological scheme, not limited to the Judaeo-Christian tradition. This scheme relies on the privileged nature of the relationship of knowledge between the gods and humankind, as in the myths of Icarus and Prometheus, and/or on their being costs for sampling and discovering what is forbidden, as in the myths of Pandora5 and Psyche6 (or more recently, of Lady Godiva7 or the Lady of Shalott8). The mythical or religious roots of Bluebeard lend the question of curiosity a particular depth. It is not just any disposition; it is, on the contrary, the very first disposition which humankind gave itself; it is curiosity and curiosity alone which is at the beginning of our history; after God provided the main elements and the scenery, it is curiosity that sets the human adventure in motion. At least in the Judaeo-Christian imagination, curiosity therefore intervenes long before ‘habit’ and ‘self-interest’, which sociology and economics nevertheless try to impose, one set in opposition to the other, like primitive matrices for all behaviour!

The mythical and religious origin of curiosity lend it a particular quality, by reminding us of its relation to sacred questions, to the ordering of knowledge, and to respect for Scripture. Before the development of modern science, curiosity was at the heart of the tension between natural philosophy and religion, and dealing correctly with this tension was a major challenge for social order as well as for religious power. For the fathers of the Church, the problem consisted in making the teachings of Aristotle, for whom ‘all men, by nature desire to know’ (Metaphysics book Ab 980 a 21), compatible with Scripture, which forbade access to the tree of knowledge. The difficulty is best expressed in Saint Augustine’s famous confession concerning curiosity. On the one hand, Saint Augustine recognises that curiosity (curiositas) is a passion which, like its two sisters’ pleasure (voluptas) and pride (superbia), is from both a spiritual and biological point of view inherent to the human condition:

To this is added another form of temptation more manifoldly dangerous. For besides that concupiscence of the flesh which consisteth in the delight of all senses and pleasures, wherein its slaves, who go far from Thee, waste and perish, the soul hath, through the same senses of the body, a certain vain and curious desire, veiled under the title of knowledge and learning, not of delighting in the flesh, but of making experiments through the flesh. The seat whereof being in the appetite of knowledge, and sight being the sense chiefly used for attaining knowledge, it is in Divine language called The lust of the eyes (Saint Augustine 2005: 113).

On the other hand, Saint Augustine is wary of the dangers of curiosity, which he sees as steering us towards futile and vain knowledge and distracting us from serious and pious thought:

From this disease of curiosity are all those strange sights exhibited in the theatre. Hence men go on to search out the hidden powers of nature (which is besides our end), which to know profits not, and wherein men desire nothing but to know. Hence also, if with that same end of perverted knowledge magical arts be enquired by. Hence also in religion itself, is God tempted, when signs and wonders are demanded of Him, not desired for any good end, but merely to make trial of […] in how many most petty and contemptible things is our curiosity daily tempted, and how often we give way, who can recount? How often do we begin as if we were tolerating people telling vain stories, lest we offend the weak; then by degrees we take interest therein! I go not now to the circus to see a dog coursing a hare; but in the field, if passing, that coursing peradventure will distract me even from some weighty thought, and draw me after it: not that I turn aside the body of my beast, yet still incline my mind thither. And unless Thou, having made me see my infirmity didst speedily admonish me either through the sight itself by some contemplation to rise towards Thee, or altogether to despise and pass it by, I dully stand fixed therein (Saint Augustine 2005: 114).

In his confession, Saint Augustine identifies an interesting series of types of curiosity which range in form from the most anodyne to the most dangerous. The first category includes all kinds of ‘spectacle’, such as the dog race mentioned in the quote, or the lizard and spider catching flies, which in the process catch our attention, or the ‘frivolous’ gossip which we at first listen to in order to avoid offending the speaker, but which we then find ourselves obtaining great pleasure from. All these forms of curiosity are reprehensible. It is less because of the objects of our curiosity, which are of no particular importance, and more because of their effect: they distract us from the Augustinian quest for knowledge of God and of oneself.9 A second category (just as reprehensible) concerns the enigmatic and unhealthy curiosity we experience with regard to unpleasant sights which functions as a perverse form of distraction: ‘For what pleasure hath it, to see in a mangled carcase what will make you shudder? And yet if it be lying near, they flock thither, to be made sad, and to turn pale. Even in sleep they are afraid to see it’ (Saint Augustine 2005: 114). It must be said, in passing, that this second, horrific form of curiosity is precisely the kind we find operating in the last part of Bluebeard. It does not operate through Bluebeard’s wife (who has no way of knowing what is on the other side of the door, and who turns away and leaves immediately, truly horrified by what she discovers), but through the reader: it is the ‘gory’ side of the tale that makes it so particularly fascinating for readers.10 Finally, a third, more significant category of curiosity involves the search for the ‘hidden powers of nature (which is besides our end)’. This is, in other words, the forbidden fruit of the tree of knowledge. Saint Augustine – like contemporaries of his such as Apuleius (Tasitano 1989) – thought that the heretical search for this type of knowledge could not be pursued other than by ‘magic’. For centuries, the idea of an almost obligatory link between ‘forbidden knowledge’ (Harrison 2001) and ‘the curious sciences’ – that is to say, the heretical practices of alchemy, astrology, necromancy, Hermeticism, and witchcraft – served to disqualify and suppress (often violently and, from the thirteenth century, with the help of the Inquisition) the numerous attempts to pursue knowledge beyond the sphere of religious thought, thus impeding the development of science.11

This recurrent confusion concerning curiosity (considered at once natural and dangerous) was in fact supported by scholastic thought throughout the Middle Ages, including by Thomas Aquinas, who eventually attempted to reconcile the one with the other: ‘Through his soul […] man is inclined to desire knowledge; thus must he humbly restrain this desire, so as not to push his investigation of things beyond the bounds of moderation’ (Thomas Aquinas, quoted in Pomian 1990). With this particular wording, Aquinas was trying to reconcile natural philosophy and religion. This attempt was based on drawing a distinction between curiosity (directed towards forbidden and therefore reprehensible knowledge) and scholarship (controlled curiosity, in other words, compatible with the teachings of the Church). The entire question was therefore a matter of appropriately directing the desire to know, of respecting the guidance of and limits defined by Scripture. Suffice it to say that these limits were very strict, and that for a long time the distinction between good and bad curiosity was completely obscured by the latter.

It was not in fact until the Renaissance and the Reformation that a breach was opened – one favourable to a freer and broader expression of curiosity. The Reformation’s contribution to this greater openness was both ambiguous and limited. On the one hand, by breaking from the pontifical monopoly and advocating a more personal reading of religious texts, the Reformation introduced a more direct relationship with the world, therefore weakening the old ‘scriptural consensus’ that these texts had offered: the criteria of truth must be able to be discussed (Houdard 1998). On the other hand, reformers, like their predecessors, were not inclined to allow curiosity free rein. John Calvin, in particular, in his Warning Against Judicial Astrology, whilst supporting in what were now accepted terms the Aristotelian nature of the desire to know, denounces the ‘horrible, endless labyrinth’ and the ‘folly and superstitions’ into which men have fallen ‘since they have unleashed their curiosity’ (Calvin 1842: 130). In the same text, Calvin has no fear of claiming, like other demonologists whom he joins here (Jacques-Chaquin 1998b), that mathematics often serves as a refuge for astrologists in search of an image of respectability.12

He even goes so far as to continuously warn his contemporaries against all curiosity which is too focused on his own doctrine of Election, to the extent that behaving in this way is seen as consisting of a search for the impenetrable will of God, and thus to risk the formation of incorrect ideas about divinity (Harrison 2001).13

If the Reformation therefore played a role in the advent of a more curiosity-based relationship with the world, it was very limited, and in any case took place on a much smaller scale than the social changes of the Renaissance which partially preceded and accompanied it. With regards to the issues we are concerned with, these changes took the form of two major innovations: a multiplication of the number of cabinets of curiosity and the advent of modern science.

Cabinets of curiosity are astonishing private spaces, the ancestors of our modern museums (Impey and Macgregor 1985; Findlen 1994), in which, from the fifteenth century, certain individuals started storing large numbers of intriguing, bizarre, and extraordinary objects. Specifically, the strange items in these cabinets that have been subject to a magnificent autopsy in the work of Antoine Schnapper (1998) are presented in a register that occupies a space somewhere between curio and curiosity (in French ‘bric-à-brac’, which arrived in English with a related but distinct meaning during the Victorian era). Because of the often substantial financial resources required to assemble these collections, this was a practice dear to the hearts of Europe’s finest. This was not always the case, however, given that the world of collectors included people of very diverse circumstances and wealth, including collectors of antiquities, the bourgeoisie, doctors, scientists, and so on. As for the curiosities themselves, the cabinets threw together haphazard collections of objects ranging from cultural artefacts, such as medals, paintings, Greek and Roman antiquities, to handicrafts – jewellery, for instance – to miniature heads and figurines, even to natural objects from the vegetable, animal, and mineral kingdoms. These latter objects were collected because of their spectacular qualities (for example: tulips, birds of paradise, gemstones), or their legendary connotations (the Jericho rose; a Remora fish – harmless looking but nonetheless, according to Ovid, capable of slowing down ships – basilisks, unicorn horns, and eagle-stones – a kind of geode which, according to Eastern legend, could be placed in an eagle’s nest in order to encourage propagation) and/or their curative abilities: the Jericho rose, unicorn horns, and eagle-stones that I just mentioned are also known for their medicinal virtues, the first for easing childbirth, the second for healing wounds, and the third for preventing miscarriage. Finally, greatest interest was shown in intriguing objects found at the intersection of the three kingdoms, which appeared to call their separation into question: for example, fossils – animal or vegetable rocks – and coral, apparently a vegetable-mineral.

Cabinets of curiosity appeared at a very particular time, when objects were being discovered faster than knowledge itself. That is to say, they were being discovered before we had the knowledge that could categorise them, or explain their origins, or determine their exact characteristics and virtues. The collectors of these curiosities marvelled at and expressed perplexity about everything they collected. Rather than try to explain the thousands of enigmas and puzzles, they tried to record them: giants’ bones, amber containing insects, minerals which attract iron, extraordinary animals, unknown objects and monsters that provoked disgust, wonder, and desire to know (Daston and Park 1998). All of these curiosities created the possibility if not of numerous explanations then at least of the likelihood of questions being left open. As Krzysztof Pomian (1990) explains – the author to whom we owe the most accomplished investigation on the subject – the logic behind these collections is that of a relationship between the part and the whole: every cabinet works as a microcosm, a synecdoche, a place which is meant to ‘represent the invisible’ and provide access to the entire universe. Pomian beautifully defines the items that these collectors assemble as ‘semiophores’: in other words, objects filled with signification intended to make us able to see what is extremely distant both in time (see: a collection of antiques) and space (see: a collection of exotic objects). To put it in Bruno Latour’s terms (1993), collectors, even if driven by the desire to know about the ‘modern’ in the making, are themselves very much ‘non-modern’: they pile up objects more than they classify them14 and they scarcely make a distinction between the human and the non-human. The logic which motivates them is concerned with the particular, and thus neither the universal nor market value: each piece is collected according to its own merits, regardless of its exchange or use value, and without a principle of commensurability that might allow their organisation.

The desire to understand and to explain was of course very much present, but neither was it a priority – collectors were not necessarily scholars – nor could these concerns make much progress given that attention tended to be confined to singular entities, and to noting their marvellous appearance rather than their inner and often inaccessible structure. And although, from the seventeenth century, these curious collectors became interested in scientific instruments, it was as collectors’ items and not as instruments of knowledge: for example, when microscopes and telescopes were collected it was as a means of multiplying fascination rather than increasing understanding about the world. That the primary attraction was the wonder of an individual object, rather than for a systematic understanding of things, can be easily explained by taking two contextual elements into account. On the one hand, the discovery of the New World and the exploration of other exotic lands opened Western eyes to numerous novelties and enigmas (some spectacular and some of great potential significance), which science, still in its infancy, was not capable of explaining. On the other hand, the continuing prestige of classical forms of knowledge and the authority of religion remained as sources of confusion. At a time when the direct observation of phenomena and experimental verification were often out of reach, it was difficult to imagine how theses propounded by the great classical authors could be called into question (see Ovid and the supernatural power of Remora). Furthermore, the weight of forms of religious authority shaped and heavily constrained collectors’ cognitive processes. Contrary to what one might think, the Church was not completely alien to the art of collecting, given that the practice had largely been anticipated in its accumulation of relics, paintings, statues, and even ‘giants’ bones’ in places of worship (Pomian 1990; Schnapper 1988). However, if ‘giants’ bones’ or ‘unicorns’ horns’ were being collected, it was precisely because the existence of these extraordinary creatures was mentioned in the Scriptures. Both the belief in and the weight attached to Scripture placed very narrow limits on possible explanations and discussion. Even Ambroise Paré, a sceptic amongst sceptics, could do nothing but bow in the face of dogma: he did not dare to question the existence of unicorns, confining himself instead to discussing the therapeutic virtues of their twisted appendages. If fossils were intriguing, it was because of an inability to understand how fish could be found on top of mountains. The account provided by Genesis, which was beyond question, may have featured the Flood, but the latter was hardly compatible with the rising of the sea. In order to reconcile the irreconcilable, one suggestion was that animals were generated spontaneously by rock and would only be released once they were perfect. All in all, the marvels of nature and religious dogma combined to hamper knowledge and to increase astonishment. The cabinets of curiosity were therefore like antechambers of the science to come, the paradox being that, at a time when the world was suddenly being invaded by new objects from the world over, religious objection to knowledge sharpened the very curiosity it was meant to restrain.

However, the influx of new objects of curiosity would ultimately encourage the emergence of a less superficial and more scholarly approach to knowledge, and would therefore shape the gradual emergence and increasing autonomy of modern science. It is well understood that developing independent forms of knowledge about nature was particularly risky at a time when any attempts to obtain knowledge which differed from the content of Scripture might be suspected of heresy, or even links with the Devil (Harrison 2001; Jacques-Chaquin 1998b). The emancipation and development of modern science began just before Perrault at the very start of the seventeenth century; it became a key topic in academic circles in the following decades (Kenny 2004), and triumphed with the Enlightenment. Two major factors contributed to completely turning the image of scientific curiosity around (and thus to converting a desire for knowledge that was blasphemous and condemned by the Bible) into a force that would benefit society.

The first contribution was that provided by the English scholar and philosopher, Francis Bacon, who between 1603 and 1605 managed, for the first time, to develop a method of reasoning compatible with religious Scripture but nevertheless able to overturn the subordination of knowledge to religious authority. The first part of the argument consisted in arguing that since God had endowed man with cognitive skills, the knowledge of the world was neither forbidden nor above our capabilities: ‘God hath framed the mind of man as a mirror or glass, capable of the image of the universal world’ (Francis Bacon, quoted in Harrison 2001: 279). This formulation is very subtle. On the one hand, to claim that the knowledge of the world is accessible to man does nothing more than repeat the classical Aristotelian position which the guardians of Scripture had long since conceded. However, on the other hand, to say that God conceived the human spirit as a mirror, capable of directly reflecting the state of the world, was to open the way for a new approach. Largely favoured within Protestantism (to which Bacon personally adhered), this consisted in proposing to complement the reading of the great book of Scripture, and the Bible, with that of the new ‘book of nature’ (Mukerji 1983; Findlen 1994).

The second part of Bacon’s argument was just as astute and innovative. The idea involved conceding the existence of forbidden knowledge (that which produced pride) in order to better emphasise another kind of knowledge, that which, on the contrary, would promote charity – the greatest of theological virtues, in other words. Once again, the concern to separate ‘proud knowledge’ and knowledge guided by charity falls within a longer philosophical tradition, given that it reminds us of the distinction drawn by Thomas Aquinas between curiosity and scholarship. However, at the same time as connecting with previous ideas, Francis Bacon managed once again to innovate, by suggesting that it was possible to define the proud or charitable nature of knowledge in light of its usefulness. With this new criterion, it then became possible to distinguish between knowledge acquired through vanity or pride, guided only by the ‘pleasure of curiosity’, and virtuous knowledge, directed not towards the personal satisfaction of the senses or of the mind, but towards a search for knowledge that is useful in life. This would repair the damage caused by the Fall. By providing a new reading of Genesis, this twin argument manages to overcome the dogma which had stood in the way of scientific progress. The promoters of the new sciences had finally found a way of developing their work without overly offending the religious authorities and risking the wrath of the demonologists. Robert Boyle referred to Bacon in order to defend his experimental philosophy and a practice of science consistent with reading the book of nature; the members of the Royal Society, who first resisted Bacon, Boyle, and Newton’s pioneering curiosity (Ball 2013), finally recognised their debt to Bacon, who had given them legitimacy and had opened the way for their activities to take off (Harrison 2001).

The second contribution to the emancipation of science and the acceptance of curiosity came from authors such as Descartes and Montesquieu. Descartes’ original contribution, shortly after Bacon and long before Montesquieu, also consisted in addressing curiosity not from a religious point of view, but through a methodological approach. Based on the idea that the intellectual capabilities of man were limited, Descartes argued that these capabilities could not encompass everything, or else there would be a risk of errors of judgement. He therefore condemns unbounded curiosity, and in particular the curiosity which is aimed, according to him, at the pointless inventory of all natural entities. He does this in order to argue in favour of a desire for knowledge that is deliberately limited to objects that we can tackle with the tools provided by reason and method (Pomian 1990; Harrison 2001). Later, and after Bluebeard had been written (1697), Montesquieu agreed by saying that

[w]hat makes the discoveries of this century [eighteenth] so admirable are not the simple truths that we have found, but the methods for finding them […] It is not a single brick in the edifice, but the instruments and machines for constructing the whole building (quoted in Jacques-Chaquin 1998a: 19).

Without a doubt, and as has been demonstrated by Christian Licoppe (1996), the previous ‘curiosity for curious things’ played an important role in the development of modern science throughout the second half of the eighteenth century – the period between Descartes and Montesquieu. This occurred through the organisation of spectacular experiments where a curious public (generally deliberately chosen either at the time of the experiment, or when it was later recounted) was called upon to give its approval to the events observed and the conjectures inferred. However, this was ultimately a period of transition: a ‘curiosity-based’ knowledge regime was, little by little, sidelined in favour of methods of argumentation revolving around the usefulness and exactitude of scientific proposals. A science playing on the curiosity of public experiments was replaced by a ‘cooler’ form of knowledge, determined less by the excitement of visual and collective perceptions than by the possible usefulness of the knowledge produced. This was whether this knowledge was employed by political authorities (in France); by economic and financial institutions (in England); in the internal organisation of museums and the establishment of their catalogues (which contributed (especially in Italy) to ‘codifying the culture of curiosity that defined the experience of the collection’ (Findlen 1994: 44);15 in the drafting of laws meant to explain the reproducibility of the phenomena studied; or in the increasingly hushed, closed world of scholars’ studies and the academies – for instance, in the Académie des Sciences in France or the Royal Academy in England (Licoppe 1996).

Thereafter, the Enlightenment completed the liberation movement of libido sciendi (the craving for knowledge) from religious tutelage: the limitations of science and human curiosity were, from then on, not cultural, but technical and cognitive (Jacques-Chaquin 1998a). Paradoxically, accompanying the triumph of knowledge over religion was a disenchantment not only with prior beliefs, but also with curiosity. This was also a process which clearly demonstrated the decline of analogical thinking (which, for example, claimed nuts could heal the brain) in favour of taxonomic thinking (which tried to reduce the world to a finite series of universal criteria) (Foucault 1973). Consider the case of ornithology, for instance. We see a move from Rondelet’s impressionist sixteenth-century classifications (birds with strong beaks, singing birds, birds living beside water, and so on), towards the morphological classifications of Francis Willughby a century later (based on anatomical criteria (Schnapper 1988: 61)). The singular is finally reconciled with the universal: with the development of robust methods of classification, able to draw together a series of singular events within the same structure – what Descartes had feared so much (uselessly overloading the memory through the vain science of the inventory) finally made sense. With the upsurge of taxonomy, collections were ordered and divided, with curiosity taking a step back in favour of examination. Employing the general laws of physics and chemistry, and supported by the use of methods of dissection and an analytical approach, single objects were split into ever more simple elements. The irreducible strangeness of creatures thus became the simple expression of universal combinations. Paradoxically, science had triumphed over both the Church’s prohibitions on curiosity as well as over the forms of guilty curiosity which its practices were meant to arouse:

In the last decades of the eighteenth century, naturalists increasingly turned towards observation, experimentation, and reconstitution. As Cuvier said in 1808, ‘natural history […] which the general public and even some scholars still have rather vague ideas about, started to be recognised for what it really was: a science whose aim is to use the general laws of mechanics, physics, and chemistry to explain particular phenomena demonstrated by different natural entities’. This leads us to apply classificatory criteria to natural phenomena which no longer owe anything to visual inspection. Thus, minerals are now classified according to their chemical composition, which is only revealed thanks to the destruction of the samples being studied and the use of measuring instruments. And animals are classified on the basis of their anatomy as studied under the microscope; this means that specimens have to be removed from their jars, in which they had been preserved and exhibited, so they can be dissected to the point where very little is left. As for fossils, they are now classified in relation to their original organisms, which involves comparative anatomy, whilst being integrated into a time-based, reconstituted series, thanks to the presence of fossils in strata whose position allows their order of succession to be inferred. The golden age was coming to an end. We were now entering the age of laboratories and fieldwork (Pomian 2004: 35–36).

At the same time, curiosity began to become ‘economised’, which completed the general sense of disenchantment: over time, the commercial potential of curiosities was seized upon by traders: these grew in number, invaded the world of collectors, contributed to and organised collections, authored catalogues, and converted the previously private accumulations of the collectors into a market for collected objects. The market became the place where both collectors and scientists obtained the curiosities which fascinated and interested them (Findlen 1994: 170 sq.), as well as the place where these same objects were put into circulation. If we could give only one example to illustrate the consequences of this movement of commercialisation, it would have to be the fate of the poor unicorn: traders supplied such a large number of narwhal tusks (those twisted horns so dear to collectors) that they ended up ruining the unicorn legend by both demonetising and discrediting it (Schnapper 1988). In other words, science and forces of economic transformation joined together to restrain curiosity, collections, and the number of collectors. The very last source of hesitation was that of the Encyclopédie,16 torn between its own ambition for knowledge and the risk of vain curiosity (Jacques-Chaquin 1998a), under the influence of La Bruyère’s brutal satire against tulip collectors (Schnapper 1988). However, this hesitation was no longer produced in the name of religion, but was rather grounded in knowledge guided by reason: these were the dying embers of a long debate, which had already moved towards an era of tempered or even forgotten curiosity.

We have now reached the time when the major divisions that structured modernity since the Reformation ended as they became brought together: after Protestants had launched their own modern project by attempting to separate the divine and the Church, scientists in many ways prolonged their efforts by seeking to separate the world of things from those of the state and religious authority (Shapin and Schaffer 1985). Eventually, in the eighteenth century, the new separation of the economy from religious and civil control resulted in the disentanglement of all of the political, religious, and economic elements which the old world had mixed together. Just as Protestants had built their doctrine on the definition of a direct link between the subject and the word of God (the Bible), scientists had founded their knowledge on the establishment of a direct link between the work of a researcher and the things he studies. Now, with Adam Smith at the forefront, the new economists also intended to break away from their old political affiliations (associated with the heritage of mercantilism) by proclaiming the transcendence of market forces. This would protect economics from all human and spiritual domination for the benefit of the dictatorship of ‘interest’, created ex novo, as a new, natural disposition (Hirschman 1980). The economic, the political, and the religious were each separated while the manner in which they could be recombined was reinvented: ‘The laws of commerce are the laws of nature and consequently the laws of God’ (Polanyi 1957: 117); laissez-faire had to be respected in order to respect the divine/natural order to things.

The proliferation of goods was accompanied by a general movement towards materialism, science, and economics. Contrary to what is understood following Weber, Protestantism did not play a privileged role in this development: the love of gold, finery, possessions, and the search for profits for profit’s sake, which Weber postulated as the consequences of capitalist behaviour, in fact preceded the advent of the economics of accumulation (Sombard 1966: 32). Similarly, at the root of the modern economic world we find Veblen’s pre-capitalist ‘leisure class’, which was born out of the disappearance of both the feudal system and the predatory nature of the aristocracy. If the lower classes were still limited to a subsistence-level existence (Veblen 2013), then the new leisure class was giving pride of place to salons, speech, and manners, as well as to luxury and comfort, presents, feasts, and ostentatious behaviour. Of course, the leisure class (inclined to spend) was quickly replaced by the middle class (inclined to save). Long before Weber’s Protestants, rich Italians (such as, starting in the fifteenth century, the architect Alberti) pushed problems of household management to the fore by discovering that it was possible to become rich not only by earning a lot of money, but also by spending less (Sombart 1966: 106). However, the middle class’s inclination to save was – in fact similar to Weber’s Protestants, who followed – purely relative. Whatever the middle class men did not personally consume was done so by those that surrounded them: for example, by domestic servants (Veblen 2013: 49) and wives who were responsible by proxy for the master of the house’s consumption. The former did so out of duty and the latter to guarantee the household’s reputation:

It is by no means an uncommon spectacle to find a man applying himself to work with the utmost assiduity, in order that his wife may in due form render for him that degree of vicarious leisure which the common sense of the time demands […] the wife […] has become the ceremonial consumer of goods which he produces (Veblen 2013: 57).

This duplicitous behaviour is not the late flowering of curiosity. On the contrary; curiosity has been coextensive with the history of modern capitalism. In fact, the double articulation of production and consumption was based less on a hypothetical division of duties between Protestants (inclined towards saving and production) and Catholics (inclined towards spending and consumption), and more on the intimate entanglement of saving and consumption behaviour amongst all of the actors involved:

Many of the seventeenth- and eighteenth- century English businessmen of Protestant faith who built up their enterprises by careful reinvestment eventually used large portions of their wealth to become the new gentry, building great country houses on their newly acquired estates and filling them with lovely artifacts (portraits, chairs, murals, and chinaware) that testified to their high social station. These entrepreneurs are easy to type as Protestant businessmen in the Weberian sense if one simply ignores the way they lived at home. But such ignorance is costly. It masks the fact that pure ascetics or pure hedonists were rare in early modern Europe; most people, whether Protestant or Catholic, combined the two tendencies (Mukerji 1983: 3–4, my italics).

The worlds of collecting and consumption became progressively blurred, at the mercy of a movement of ‘publicisation’ and democratisation. The English historians McKendrick, Brewer, and Plumb (1982) and the sociologist Chandra Mukerji (1983) have clearly demonstrated how, throughout the eighteenth century (after Bluebeard, then) there was a craze for the exotic and for novelties amongst the working classes. The private collections of old, which had required considerable wealth, took on different and more accessible forms. This involved new, less costly activities: growing seeds and bulbs in the garden for show, buying ribbons and printed textiles which brightened up wardrobes, and visiting zoos and botanical gardens, which gave people a cheap way of discovering the extraordinary animals and plants that had been brought from the New World and the colonies. However, the progress of science and the progressive generalisation of the unusual ultimately resulted in disenchantment. The commercialisation and the assignment of monetary value to everything eventually imposed interest as a substitute for all other passions (Hirschman 1980). From then on, economics became concerned with self-interest, and sociology with habit, with both forgetting all other motives of action, including curiosity, which, as we shall see, was abandoned to the market.

2

Bluebeard: Towards the Marketisation of Curiosity

We can see that venturing into Bluebeard’s cellar and delving deep into the foundations of the ‘wonderful house of horrors’ helps us to better understand who this enigmatic man is and what is at stake in his tricks, beyond his particular case. Bluebeard appears at a pivotal moment, just before modern science established itself, and just before the generalisation of consumer society. Perrault wrote his tale at a time when collecting practices were reaching their peak, while also coming into competition with quests for gold, success in business, and material pleasure. With an eye on these historic changes, we can now, therefore, study the differences between Genesis and the character of Bluebeard on the one hand, and, on the other, the relationship between Bluebeard’s collecting practices and this new economic configuration.

The main difference between Genesis and Bluebeard concerns, of course, the main protagonist. Bluebeard combines, in a single figure, the Serpent (traitor), Adam (spouse), and God (punisher), whilst at the same time being quite different from each. The blurring/differentiation of these figures is the fruit of a certain identity crisis: Bluebeard imagines himself neither as the weak Adam1 of the inaugural garden of Eden, nor as the more contemporary husband who accedes willingly to his partner’s wishes, also the subject of the tale’s ‘moral’ (see below), but rather as the domineering (if dated) figure invented by God to punish Eve. In its own way, the tale begins the movement towards secularisation, of which it is also a product: there is no imperious God in the story, nor a tempting serpent, but rather simply a man, however frightening he may be. This point is worth emphasising: with the exception of his enigmatic hirsuteness, which is only there to focus the reader’s attention, Bluebeard is far from the fantastical creatures which normally fill fairy tales; he is neither ogre, nor giant, nor sorcerer.2 Bluebeard is of course monstrous, but no more or less so than the ‘serial killers’ of the past (before Perrault: Gilles de Montmorency-Laval and Henry VIII, and after: Landru3) and the present. The character could even be considered more pathetic than frightening: he is a ‘man of possessions’, a misogynist and misanthropist who dreams of himself as both God and master, unable to become either, and who is rejected because of his blue beard, perhaps because he is not, or is no longer, blue-blooded. Bluebeard is frustrated because it is not he that is attractive to others, but rather his riches. So he kills his successive wives because they let him down; this is undoubtedly because they break their promises but equally because they systematically fall for an illusory materialism, one which, paradoxically, he also suffers from. Nor does the tale explore a universal mythical question, but rather delivers an anachronistic testimony about an era which is coming to an end: the central character, his businesses, and possessions, already have one foot in the future modern middle class, while his behaviour demonstrates that he still has one foot in the old world. Bluebeard is nostalgic about a mythical time, characterised by attitudes and values which tend to be, if not disappearing, then at least becoming less relevant (respecting promises, authority, obedience, the primacy of spirituality over material goods, as just a few examples). He is, however, marked by the inaugural zeugma which defines his identity according not to who he is, but to what he has (‘There was once a man who had fine houses, both in town and country, a deal of silver and gold plate, embroidered furniture, and coaches gilded all over with gold’; my italics) including his fateful beard (‘But this man was so unlucky as to have a blue beard’; my italics). In light of these shortcomings and contradictions (as with so many victims used as scapegoats), he condemns his wives as if he is vainly trying to forget that he is just like them, and was so long before they were, having become unworthy of the values he defends.

Box 1. Bluebeard and Psychoanalysis, or the Misfortunes of Misplaced Curiosity

Since Bettelheim (1976), it has become conventional to reduce tales to psychoanalytic fables. Bettelheim himself used Bluebeard as a way of applying his universal analytic framework, and in order to explain that the blood on the key signified that the heroine had had extramarital relations whilst her husband was away; thus the tale would be seen as confronting us with a sexual curiosity which it of course condemns.4 If I were to adopt the same approach (on which Freud’s successors were so keen) of tracking down the juicy motive, I could attempt another explanation, based on an inversion. In this case, I could place the woman in an active role with the husband adopting a passive one: on the one hand, the woman deflowers the forbidden room using a phallic key, risking a bloodstain which cannot be removed; on the other hand, her husband limits his speech and remains in the background. From this inversion, it would therefore be possible to deduce that Bluebeard is impotent. Everything would then become clear: the character would compensate for his sexual shortcomings not only with his absence, but also by putting his power to the test, as well as by transferring activity onto his wife/wives, and then finally by killing the person who represents him as the substitute for an impossible relationship (Eros and Thanatos: the theory is well known!). Psychoanalysis could even support this audacious interpretation, by referring to one of its historical variants – one that appears much later but which is equally troubling: the case of Louis XVI, a king who, when experiencing difficulties consummating his marriage and forced into political inaction, found himself (almost) like Bluebeard, distracted by his hobby of locksmithery, before this double inaction condemned both him and his wife to the fate we well know! In fact – and abandoning the historical variant I mention ‘just for fun’ – the theory about Bluebeard’s impotence seems more reasonable than Bettelheim’s interpretation. It has the advantage of proceeding carefully based only on the elements provided by Perrault, without having to involve lovers who are difficult to locate in the story (although admittedly, there are plenty of cupboards in which to hide them!). We can see that a psychoanalytic approach is never short of imagination (or fantasy?!). However, I believe this exposes it not only to the risks of over-interpretation, but also to the dangers of a certain obliviousness to other, more likely interpretations. By focusing too much attention on motivations which may not exist, we in fact end up not seeing all the rest – as in (upstream) the clear and pregnant precedent of Genesis, and (downstream) all the economic lessons which stories convey quite explicitly; no hermeneutics, other than reading carefully, is needed to explain these. Undoubtedly it is Gustave Doré who best grasped (by accident?) this point: his engravings show heavily dressed figures facing objects which are as bare as they are intrusive, perhaps to signify the extent to which the body is so much less important to this story than objects. The same could be said, of course, for the – very intense – ways in which the figures regard these objects.

Bluebeard is therefore a character who is both trivial and mysterious, but for reasons which we did not expect: he is intriguing less because of the enigmatic colour of his beard or the sexual content of the tale (see Box 1), and rather because of how he is positioned economically. The character is trivial in the sense that he is attached from the outset to a completely materialistic economy, where people are defined by neither their birth (like princes), nor their origins (like in the Middle Ages), nor their job (like modern subjects) but their possessions. Bluebeard is a fairy-tale character in a tale of facts,5 immersed in a purely materialistic universe. He nonetheless remains mysterious because he is a man about whom we know nothing, other than the fact that he has a lot of possessions, ‘both in town and country’; in other words, everywhere and nowhere. We do not know by virtue of what economic logic his possessions were acquired (inheritance, through private income, production, trade?); they were accumulated, but it appears they cannot be alienated. Bluebeard can therefore be considered as an ambiguous figure who encompasses all of these elements: assets, savings, production, and consumption/ostentation.

It is here that we touch upon the connection between curiosity and economy which would become established in the years to come. Curiously(!), the analogy we were most expecting is the one which is least effective:6 Bluebeard no longer corresponds to the figure of a collector of curiosities, despite the presence of numerous cabinets at the time: the collector from Castres (Pierre Borel, who was a contemporary of Perrault, himself knew of sixty-seven in France alone; furthermore, during this period there were ‘hundreds, if not thousands’ of cabinets of curiosity in Europe (Pomian 1990). As an initial approximation, one could certainly say that Bluebeard was a collector; twice over, perhaps, given that he collected both objects and women. In this respect, he corresponds to a traditional collector of curiosities, accumulating objects and animal carcases as well as human bodies in the form of mummies, shrunken heads, and other more or less well-preserved monsters (Pomian 1990; Schnapper 1988). However, whilst diversity in collections was the rule, and homogeneity the exception, the women that Bluebeard collects are identical. And if he is collecting them, it is only because he is unable to find the perfect wife who follows his wishes, and not, apparently, because he initially intended to multiply his crimes and trophies. But as for the rest, all the goods he possesses, in other words, Bluebeard has an entire collection of objects, the wealth of which actually masks great poverty: it all boils down to either containers that are rather hollow (‘two great wardrobes’, ‘[crockery]’, ‘strongboxes’, ‘caskets’, ‘apartments’, and a ‘little closet’), or to contents like precious stones and metals and therefore to the value they represent. We are confronted with a one-dimensional and pecuniary approach which is demonstrated by the rather vain repetition of the words ‘gold’ and ‘silver’, which little by little dissolve the real value of the associated objects (‘silver and gold plate’ (twice!), ‘coaches gilded all over with gold’, ‘gold and silver’, ‘jewels’). The emergence and invasion of a monetary standard actually extinguishes the very principle of collecting, given that, by using the same yardstick to make the collected objects commensurable and fungible, they lose their irreducible singularity.7 There is therefore a second major difference with Genesis: in Bluebeard, it is no longer a matter of forbidden knowledge but rather vain material seduction – as if the symbolic fruit had become literal; as if sacred knowledge had turned into profane tastes. In the tale, the protagonists’ appetite is, in fact, not for fundamental knowledge, but rather for quite vain objects of pleasure, until they reach that abyssal, ultimate emptiness: the forbidden room – the only true cabinet of curiosity in the story, which is filled only with the women who thought it was full.

The materialistic and vanity-driven universe which Bluebeard honed to test his victims is indeed the antechamber of the movement to come: that of the economy’s emancipation from old forms of control and social relations, and towards a new order which is based on consumption and the ‘natural’ circulation of goods in the commercial sphere. We have reached the tipping point between the economy of the Ancien Régime (literally: Old Regime) and the emerging commercial economy of the middle class. This is demonstrated by the tale’s ambiguity, which, from the first to the last lines, defines a universe that is both economic and domestic.

Right from the beginning, the tale shifts dizzyingly between economic calculations and filial relationships. Filial relations take precedence over every calculation, since children are faced with the traditional obligation to accept the suitors proposed by their parents. However, in this case the situation becomes more complicated given that the two daughters are available for just one marriage. This introduces the question of choice into the heart of traditional family relations of authority. The lack of interest and embarrassment which this problem (respectively) presents initially leads Bluebeard to delegate the management of this choice to his potential mother-in-law (‘He desired of her one of them in marriage, leaving to her choice which of the two she would bestow on him’). It is then up to her to offer her daughters the choice, in a manner of speaking, of a non-choice (this second delegation is implicit in the following wording: ‘Neither of them would have him, and they sent him backwards and forwards from one to the other, not being able to bear the thoughts of marrying a man who had a blue beard’.) The opening scene thus confronts us with a particularly original situation of impossible calculability, the opposite of that faced by Buridan’s donkey (Cochoy 2002): instead of a single economic agent, Bluebeard – or his possible mother-in-law – faces an inescapable trap, consisting of the rational choice between two potential, almost identical wives (two sisters between whom one cannot a priori differentiate: they are both said to be ‘perfect beauties’, and it is only afterwards that we find out who is the younger and more naive of the two). Ultimately, it is the two potential wives who are driven towards the choice of which one will have to be chosen! This choice is yet more complicated because the agents, far from having a preference, demonstrate an identical aversion to the object to be chosen; they thus find themselves in a situation akin to that of Buridan’s donkey, as evoked by Christian Schmidt, who had to choose not between two equally desirable quantities of food, but between two poisons (here there is only one). Now, Schmidt tells us that in such a situation, one possible and rational option is abstention, and that this must be taken into account as a real choice (Schmidt 1986: 77). However, in the tale, a choice other than abstention is at play, through the presence of both obligation (the sisters know that one of them will have to yield) and calculation. It is calculation that leads one of the girls to consent, for, after experiencing the festivities offered by Bluebeard, she believes that in the final analysis her suitor’s possessions will have sufficient appeal to overcome the repulsion which his blue beard inspires in her (‘the youngest daughter began to think that the man’s beard was not so very blue after all, and that he was a mighty civil gentleman’). The difficulty of choice is resolved by a process of calculation which includes, on the one hand, the revelation of additional information about Bluebeard (the attraction of his wealth), and, on the other hand, the revelation of physical and cognitive differences between the two sisters (one is younger and therefore more naive). Whereas the first element turns a negative preference into a positive preference, the second means they can resolve their indecision (if one of the sisters was not more naive than the other, we might assume that their calculation would have been identical – to either marry or reject Bluebeard. This would have meant the problem remained unresolved. It would thus have had to be referred to the mother for arbitration, or a convention, such as the birthright of the eldest,10 would have had to be applied. Thus, we can clearly see to what extent the tale both brings into play and calls into question the old way of managing alliances. It opens up the sphere of personal dependencies to expressions of individual preference and rationality, whilst implicitly announcing the aporias that accompany this development (possible errors in calculation, logical deadlocks, a reworking of personal dependencies, among others).

The blurring of the economic and the domestic continues in the rest of the tale, this time in relation to place. What Bluebeard offers his wife is an economic space in the sense that it is a question of choosing, exploring, consuming, and evaluating the objects that are ‘supplied’. It is important to underline the extreme degree of licence which he grants his wife: not only is she authorised to visit (almost) every place in his home, but she is also allowed to show these to her acquaintances (‘to send for her friends’), and also is given an almost total freedom of movement; she is thus far from being imprisoned in the home behind locked doors, as an overly hasty reading of the tale might lead one to believe (‘to take them into the country, if she pleased’). If it were not an anachronistic expression, one could say that Bluebeard presents his house almost as if it were a self-service emporium, where one can come and go as one pleases, and of course, where one can approach the objects without fear of being hindered by human mediation. Despite this initial impression, however, the economy that is portrayed remains strictly domestic: the universe of exploration in fact constitutes a closed circuit; it is closed by the unbreakable link that then existed between marriage and the allocation of a household’s assets. The supplied objects have no price and are inalienable. We are clearly in the presence of consumption that is preferential and non-rival: the economic relationship in this case is confined to visual exploration and does not involve the acquisition of goods. If the tale does provide forms of material seduction, then this is done in the manner of ‘window-shopping’. Indeed, this is a forewarning of future market configurations (see chapter 3), which here remains highly private and illusory, narrowly enclosed within the domain of personal property and, for the moment, far removed from the open markets which are to come.

Finally, the combination of economy and family extends to the denouement. On the one hand, after the death of Bluebeard, the distribution of his inheritance commences with activities of calculation and allocation being set into motion: the heroine, who inherits all her late husband’s assets, wisely uses a portion to marry off her sister, another to purchase captains’ commissions for her brothers, and herself uses the remainder to remarry. However, the way these different sums are employed elegantly demonstrates that we remain completely immersed in an economy of accumulation and unearned income: at Bluebeard’s, there is no production; goods do not circulate but rather stay within the circle of kinship; women have no other economic existence other than through marriage, while for men, it is through the acquisition of commissions under the Ancien Régime. The intertwining of both spheres – economic calculation and the domestic economy – reminds us once again of the extent to which the economic is not unaffected by strong ties, and vice versa (Callon and Latour 1997). What is at play in the tale is not a world of personal attachments and non-calculation which then tips over into a world of calculations and individual freedom, but rather a change in proportions between these different entities. The move is towards more flexible family relationships and an extension of the rational assessment of situations.

In this movement, the motives of self-interest and curiosity play roles which are as significant as they are subtle. In the tale, self-interest does make an appearance, but simply as something that is in the service of curiosity. The distinction between these two types of motivation, and the way in which they are brought together, appear to be clearly visible in the two sequences which follow Bluebeard’s temporary departure.