1

Introduction: The Practices and Infrastructures of Comparison

Joe Deville, Michael Guggenheim, Zuzana Hrdličková

Two Comparisons

Let us produce a comparison.

The first entity in this comparison comprises the opening lines from Reinhard Bendix’s relatively early attempt to justify the comparative method within sociological research:

Like the concepts of other disciplines, sociological concepts should be universally applicable. The concept ‘division of labor’, for instance, refers to the fact that the labor performed in a collectivity is specialized; the concept is universal because we know of no collectivity without such specialization. Where reference is made to a principle of the division of labor over time – irrespective of the particular individuals performing the labor and of the way labor is subdivided (whether by sex, age, skill or whatever) – we arrive at one meaning of the term ‘social organization’. We know of no society that lacks such a principle; furthermore, we can compare and contrast the social organization of two societies by showing how their division of labor differs (Bendix 1963: 532).

The second is an extract from a chapter published just over twenty years later in the influential Writing Culture (1986a) collection, edited by James Clifford and George E. Marcus. This collection is often seen as capturing a major shift that was occurring within anthropology at the time. This approach highlighted the inevitable partiality of ethnographic truth and the way in which ethnographic accounts needed to be seen as irredeemably textual, rhetorical productions, through which cultures become ‘invented’ and not represented (see Clifford 1986). In this section the author, Stephen Tyler, takes on what he identifies as a dominant mode of ethnographic prose, rooted in ‘easy realism of natural history’, born out of an urge to ‘conform to the canons of scientific rhetoric’. Its problem, he writes, is

a failure of the whole visualist ideology of referential discourse, with its rhetoric of ‘describing’, ‘comparing’, ‘classifying’, and ‘generalizing’ and its presumption of representational signification. In ethnography there are no ‘things’ there to be the objects of a description, the original appearances that the language of description ‘re-presents’ as indexical objects for comparison, classification, and generalization; there is rather a discourse, and that too, no thing (Tyler 1986: 130–31).

This comparison provides just a glimpse into the way in which the authority of comparison itself has changed and been challenged over the course of the relatively recent history of sociology and anthropology. It locates comparison against two radically different positions: what we might call methodological positivism, in Bendix’s case, and methodological relativism in Tyler’s (see Steinmetz 2004). The comparison, thus, highlights two ends of comparative (and anti-comparative) epistemology.

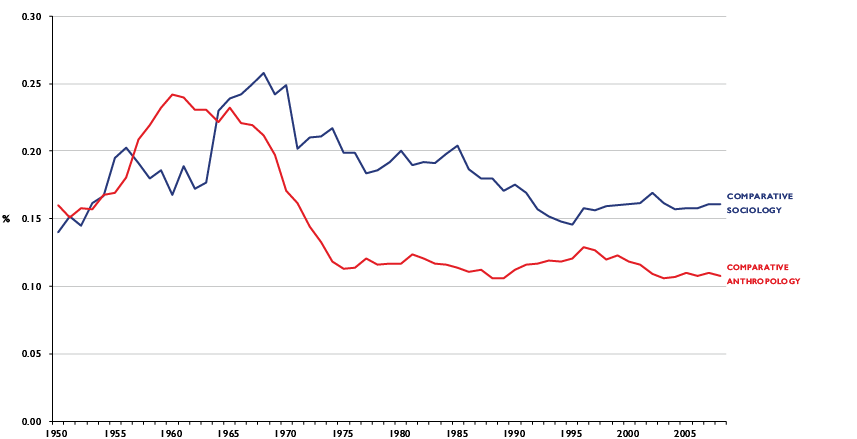

Let us produce another comparison (Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1 Relative frequency of the terms ‘comparative sociology’ or ‘comparative anthropology’ in books scanned by Google 1950–20081

The chart uses Google’s database of scanned books, narrowed down to include only those that refer to either sociology or anthropology, and looks at the changes in how often comparison is referred to in these books. The chart suggests that in both disciplines interest in comparison has increased since the beginning of the 1950s, and then peaked in anthropology in around 1960, and in sociology roughly a decade later to decline and later stabilise on a much lower level.2 Both disciplines experience a similar rise and fall of interest in comparison.

One way we can use these comparisons is to bring them together: we can see that the first two statements map onto the historic rise and fall of comparison in the social sciences, with Bendix’s enthusiasm appearing at a time when comparison was a hot topic and Tyler’s radical critique coming at a point when comparison was on the way out.

In this volume we propose to re-engage the debates about comparison by learning from the close observation of (social) scientific practice. Rather than considering the problems of comparison as those of epistemology – for instance, whether we are for (Radhakrishnan 2013) or against (Friedman 2013) comparison, or whether certain forms of comparison are ethical and legitimate (Longxi 2013) – we start by treating comparisons as objects of analysis and which we and the other authors in this collection see as involving a range of actors (human and non-human), practices, and tools. To take the above two comparisons as a comparative example, one involves us, the authors, selecting and juxtaposing two texts, while the other involves a tool that draws on a database of millions of scanned books. As we will discuss, many comparisons are at least as complex and collaborative as the latter, involving hybrid combinations of teams, funders, fieldtrips, and different media which in turn are wrapped up in distinct cultures, histories, and power relations.

Epistemological Infrastructures

Our attention is therefore on the situated practice of comparison – an approach that if not rendering the various epistemological debates around comparison irrelevant, then at least cutting them down to size. That is to say, the epistemological challenges to comparison that have arisen over the course of the latter half of the twentieth century become understood as just one part of the changing infrastructures of comparison, infrastructures that have at various points and in various different ways, rendered certain forms of comparison more or less credible.

Given that the challenges to comparison have been well documented and are touched on in a number of contributions to this volume, we will not dwell on them for too long in this introduction. The story, however, goes something like this. For a long time, comparison was seen as a crucial tool for identifying the universal forces that shaped social groupings, allowing analysts like Bendix to make the leap from the empirical to the conceptual and from the particular to the general. From the start this was itself guided by a contrast between the practices of social and natural sciences. For the social sciences, the attractions of the comparisons being produced by the natural sciences were manifold. First and foremost, scientists had proved themselves expert at using comparison to detect patterns of similarity and difference. Comparison also underpinned ideals of scientific rigour. Without it, neither principles of experimental replication, nor hypothesis testing, nor tests of statistical significance, would function. Within the social sciences, therefore, the hope was that by transferring a comparative method, its researchers might be able to emulate their natural scientific cousins and divide the world into fixed properties. This would allow them to identify not the natural laws of life, but its social laws.

However, a series of developments threatened this ambition, some of the effects of which we could try to tentatively map onto the above graph. The most major of these developments seemed, at first at least, to pertain to one discipline more than any other: anthropology. Anthropology seemed particularly wanting in the context of the major geopolitical shifts of the time. The 1960s and 1970s saw significant questions raised about its potential complicity with the European colonial project, whose damaging effects were becoming increasingly hard to ignore (see Gingrich and Fox 2002: 2). Comparison had moved from being an epistemological practice to being a political one. Seen from the perspective of this volume, this was not only a conceptual shift, but one in which the infrastructure of comparison had become newly problematic. Comparison was seen as an extension of colonialism, in which the infrastructure of colonialism served as a carrier for an epistemic project of subjecting other forms of life. The emergent issue centred on the fact that the people who embarked on the doing of comparison did so by means which were seen as compromising the very epistemological basis of their work.

The 1980s saw what might have seemed as narrow disciplinary-specific concerns flood into a number of other areas within the social sciences. First, the kinds of issues that had been raised within anthropology were shown to be as relevant to other disciplines. This became connected to a further set of attacks. A series of intellectual challenges, including Nietzschean perspectivism, poststructuralist deconstruction, postcolonial and feminist critiques, and research within science and technology studies (STS), shook many of the pillars upon which social science had been resting (see Dickens and Fontana 1994; Keane 2005). These threatened to destabilise the claim of the methods and writing practices of social research to be able to truthfully represent social life. They also threatened the idea, captured in the extract by Bendix above, that analytical concepts could be simply ‘extracted’ from empirical settings and made to circulate independently. In part this was because of the argument that different settings, different encounters between researcher and researched, possessed an inherent incommensurability (see Jensen 2011; Steinmetz 2004; Strathern 1988); in other words, they simply could not be compared in a meaningful way. And in part this was because of a suspicion of the very plausibility of concepts that could be ‘transcendent’. Attention also turned towards researchers themselves. A range of work revealed research practice as always situated and never innocent from the values and biases of the researcher (see Haraway 1989; Harding 1986). Rather than the ships and practices of the colonials, the heads and bodies of researchers became the focus for the critique of comparison. Such conclusions also threatened the standard against which social science had previously measured itself: the natural sciences. As STS researchers showed, biases could readily be found here too (Latour 1988). Some of this critique is inflected in both Writing Culture (Clifford and Marcus 1986b) and Tyler’s extract above.

Here, then, we can observe a shift from what we might call the colonial critique. In the colonial critique it was the global infrastructures of colonialism that were seen as fundamental obstacles to forms of meaningful comparison. The reflexive and epistemological critique, by contrast, while recognising key aspects of this argument, shifts attention from global practices and power relations to the individual. It is a critique that looks at comparisons as problematic effects of writing, which are seen to do violence to the uniqueness of the circumstances of the research subjects.

As we move closer to the present, we see that many if not all of these questions have lost little of their relevance.3 While many social scientists may have rowed back from more strident anti-realist stances that characterised some of the postmodernist academic discourse in the 1980s and into the 1990s, there is little sense of a desire to return to the kind of methodological positivism that preceded these challenges. Feminist and postcolonial research and STS, meanwhile, in their moves towards a more constructivist understanding of the composition of the social and material world, continue to challenge the assumed neutrality of research and its claims towards objectivity.

With the increased normalisation of constructivism, however, we can find one further important but often quite implicitly articulated recent reappraisal of the status of comparison. While the postmodernist critique of comparison was that meaningful comparison is impossible because of the damage done to the entities under comparison, the constructivist critique adopts the seemingly opposite point of view: comparison, it is argued, is ubiquitous, as can be seen in the often cited words of Evans Pritchard that ‘there is only one method […] the comparative method. And that [method] is impossible’ (used as an epigraph in both Peacock (2002) and Jensen (2011)). Comparison thus becomes meaningless, but for quite different reasons: what becomes challenged is the idea that social science could deploy a comparative practice that is distinct from the comparative practices inherent to the world. As with the reflexivist critique, this view also tends to suggest that comparison is a purely epistemic practice. From such a point of view, there is indeed nothing special about comparison. As we will proceed to outline, however, what such a view ignores are the particularities and the practices through which social science does comparison.

Given these continuing epistemological concerns about comparison, the changes in academic practice that our chart at the start of this chapter indicated should not be surprising. Within many academic departments, the challenges documented above have markedly improved the status and authority of non-comparative, small scale, case-study oriented, qualitative and ethnographic research. New seemingly non-comparative methods have also taken hold: Actor-Network Theory (ANT), for instance, and the more loose assembly of research practices which it has influenced, has exhibited a suspicion of the imposition of transcendent categories into the research situation (see Law and Hassard 1999; Latour 2005). As Bruno Latour famously put it, ‘nothing is, by itself, either reducible or irreducible to anything else’ (1988: 158). This principle is at the heart of ANT, in which the researcher does not assume an a priori separation between social and material in the conduct of research. The researcher’s main job in this situation is to identify the breaks that allow the production of continuity (e.g. the continuity of scientific practice), rather than introducing these breaks him or herself by leaping to a different comparative setting (see Latour 2013: 33).

Comparative Openings?

There are, then, a considerable number of actors exerting a potentially strong pull against the use of comparative approaches. Despite this, and against the odds perhaps, we may be seeing the door to comparative social scientific practice opening a little wider than it has done for some time. A number of books and journal collections have begun to reinvestigate questions of comparison. These have taken on important unresolved questions of epistemology – for instance, examining whether poles as seemingly opposed as comparison and relativism can, in fact, be placed into productive dialogue (see Jensen (2011) and others in the Comparative Relativisim Special Issue). They have also begun, with some overlaps with the concerns of this book, to unpick some of the challenges that face those interested in developing different, potentially more productive and potentially more reflexive forms of comparative practice. This includes asking how comparison might become ‘thicker’ (Scheffer and Niewöhner 2010), more relational (Ward 2010; Cook and Ward 2012), and/or more modest, postcolonial and attentive to modalities of difference (McFarlane and Robinson 2012; Robinson 2011; and others in the Comparative Urbanism Special Issue).

There has been a very visible push by funders for researchers to adopt comparative methods (see in this volume, Akrich and Rabeharisoa, Deville et al., Stöckelová). For instance, the stated rationale accompanying the regulatory foundation for the EU’s funding programme for the 2014 to 2020 period (known as Horizon 2020) points to the need for comparison given the increasing ‘complexity’ of the challenges facing Europe. These are challenges that ‘go beyond national borders and thus call for more complex comparative analyses to develop a base upon which national and European policies can be better understood’ (European Union 2013: 162).

There is another actor that has the potential to pull comparison in a different direction, and that is STS. This might be surprising, given that it is one of the subdisciplines that has both opened up the contingencies of knowledge production, while also developing what seems to be a non-comparative methodology. However, STS appears to be offering important practical pointers towards what the development of a new, less hamstrung comparative practice might look like.

First, STS is doing comparison. Bruno Latour’s recent major work, An Enquiry into Modes of Existence, quite explicitly puts comparison to work. Its ambition is to examine the productivity of putting, side by side, 15 different ‘modes’ through which existence is produced. Latour talks about comparison as a ‘test’, the criteria for which are implied in the following questions (if the answers to each are negative, then comparison can be considered to have failed its test):

Do we gain in quality by crossing several ontological templates in order to evaluate, little by little, what is distinctive about each one? And, an even more daunting subtest: do we gain in verisimilitude by treating all the modes at once in such a move of envelopment? (Latour 2013: 478)

We are back, then, to questions of similarity and difference. And to the ability of comparison to make a difference. What’s more, ‘irreduction’ is revealed in the book not as the principle that should underpin all investigations of social life, but rather a particular way (albeit a crucially important one in the history of STS) to follow one of the fifteen ‘modes’: the ‘network’ mode. By virtue of its capacity to differentiate, comparison inevitably engages in activities of reduction. However, this should not be seen as necessarily problematic: reduction is productive not of ‘less’ in any simple way but rather difference (see Robinson, this volume). As such, it is an operation as indispensible to analysis as it is to life (see Bryant 2013; Halewood 2011).4 In Latour’s recent book, the role of comparison can be seen as assisting us in distinguishing between (productive) reductions.

The fact that – whether for pragmatic or intellectual reasons – comparative research is being done by STS researchers offers an opportunity. Here we have a body of researchers trained in the very art of detecting how scientific techniques and technologies affect the production of knowledge, using a method which has been so often criticised for how it does just that. Undertaking an analysis of their own research (as many in this book have done) and not just the research practices of others, may help us determine in practice what the dangers and opportunities of comparison actually are for social science (see Deville et al.; Stöckelová; and Akrich & Rabharisoa in this volume).

This leads to the second point. And that is that STS is, or at least it could be, well placed to hesitate, to slow down and recognise the power and potential of its own comparative practices before making assumptions about comparison. Many critics of comparative practice make rapid leaps between ‘comparison’, ‘classification’, ‘generalisation’, and the production of knowledge understood as ‘scientific’ and/or ‘objective’. This obscures the translations and mediations that need to occur for each of these terms to have the power to define the other. Webb Keane has opened up some of these moves by demonstrating how in some social scientific settings the suspicion of comparison can be traced back to a very particular ethical project constructed in direct opposition to what he calls a ‘hypostasized version of science’ (Keane 2005: 85). This is important. As Stengers reminds us, ‘[e]xperimental sciences are not objective because they would rely on measurement alone. In their case, objectivity is not the name for a method but for an achievement’ (Stengers 2011: 50). It is a very particular type of achievement to tie comparison to the production of the very particular kinds of knowledge that scientific methodologies seek to produce. It is perfectly possible for comparison to be directed towards quite different ends.

The Uses of Comparison

To help us understand exactly how and why comparison is neither inherently innocent nor guilty of the various charges that have been levelled against it, we seek in this volume to accomplish two goals. Some of the articles focus on either one of these twin aspects, some on both. First, we seek to analyse how comparison is done, and second, we seek more productive ways of doing comparison, in part by challenging conventional comparative practices. To accomplish these goals it is important to accept the two points made above: first, that comparison indeed is a particular research practice, rather than merely a ubiquitous cognitive operation; second, that comparison as a research practice is necessarily reductive, and this is not in itself problematic.

Rather than dwelling on the epistemological concerns outlined above, then, it makes sense to look in more detail into the different uses of comparison and to begin to be able to ask critical questions about where and in what ways we practise comparison and with what ambitions in mind. We maintain here, as do the authors in this collection in various ways, that comparison can and should have uses that move far away from how it has been understood previously. We also maintain that focusing on the uses of comparison can help to free us from many of the attendant epistemological worries (see also Krause on this issue).

Thus rather than insisting on the problems associated with previous comparative research, and making an exception for non-comparative qualitative research in the mistaken assumption that it is automatically less reductionist, we insist that research is in itself a risky and necessarily reductive practice. This means that we should therefore ask where and when we want to reduce and with what goals in mind.5

Competition, for instance, is a particularly radical and often harmful form of comparison, as for example when it puts entities into a contest without having a theory of what guides the outcomes (for example, in the case of measuring academic productivity (see de Rijcke et al.)). Or there is comparison as critique (see Krause): it shares with competition the idea that we can use another object to assess the object in front of us; to understand what is good or bad about this object, or if we need another object that is different from, and better or worse than, whatever we are interested in. A number of writers have also noted how comparison may be pedagogic and creative: it allows the person or entity doing the comparison to learn from having objects, arguments, statements, and empirical phenomena contrasted with each other and, as a result of this contrast, for each to potentially emerge more clearly defined than before (see Schmidt 2008: 339; Stengers 2011: 62).

Comparison as Creativity

With this starting point established, it now becomes possible to compare different ways in which entities are constructed through comparison. The focus can thus move from criticising the construction of categories per se and the brutality with which objects are forced into categories through comparison, to analysing various forms of category creation. The construction of entities, and the reduction of the world in accordance with such entities, becomes visible as a process that is difficult, certainly, but also adventurous and creative. Throughout this volume, we can observe a number of such strategies. They all confidently establish categories, yet do so in a reflective and sometimes playful way.

The first strategy is to undermine the seeming self-evidence of the categories being used in a particular comparative undertaking, as can be seen in the articles by Akrich and Rabeharisoa, and Deville et al. In both studies, the self-evident category appears to be the state, yet in each case the authors dismantle the idea of a state as either homogeneous or consistent in different settings; instead the category of the state divides into various subsets, containing a varied and unpredictable selection of entities. In both, then, it turns out that states are above all convenient starting places for research, for the simple reason that they provide distinct legal and organisational contexts in which the research objects (patient groups and disaster management) operate.

A second version compares comparisons between social scientists and the field (see, to varying degrees, Akrich and Rabeharisoa, Deville et al., Gad and Jensen, Lutz, and Meyer). The idea here is based on the ubiquity of comparison in a context distinct from social science. This is a reflexive move which follows many other forms of constructive reflexivity in the social sciences. For example, Boltanksi and Thévenot’s theory of justification is built on the observation that critique is not only in the hands of social scientists but also part of lay discourse, and that critical theory thus needs to turn into a theory of how critique is practised (Boltanski and Thévenot 1991). The reflexive comparisons in this volume similarly start with the observation of pre-existing comparisons in the field and use these to rethink the comparative practices of social science. The conclusions that stem from such a rethinking differ, however: some authors argue that social science should follow the comparisons in the field (Gad and Jensen, Lutz), while others maintain that there is something distinct about an explicitly directed social scientific approach to comparison (Akrich and Rabeharisoa, Deville et al., Meyer).

A third version creates different entities by turning towards asymmetrical comparison. Comparative asymmetries often follow from the need to discover the tertium comparationis. While normally the tertium comparationis is assumed to dictate the category of objects being compared (a state being compared with other states, etc.), it may help to embrace forms of analysis that shift across multiple comparative registers, with no desire to produce cleanly balanced comparisons. Categories of object might be compared with each other, with then further comparisons brought into play by shifting across different planes – across not just space but also time, for instance (see the discussion of Faria’s chapter below).

The Comparator and the Practising of Comparison

To claim that comparison is always grounded in infrastructure forces us to analyse the relationship between such infrastructures and the practices of comparison. This volume is thus also concerned with the ‘nitty-gritty’ or the practical level of comparative practices as they are deployed across various social scientific comparative projects, the often unseen and unremarked dimensions of comparison upon which research practice nonetheless utterly depends. Akrich and Rabeharisoa, Deville et al., and Stöckelová each conduct types of auto-ethnography to show the diverse ways in which comparisons can be done. These contributions clearly show that comparative research hinges on a multiplicity of factors ranging from a particular zeitgeist (or research fashion), to the project structure and proposals made to funders, to the inner workings of the entity conducting the comparison. The latter is an entity we call the ‘comparator’ (Deville et al., this volume).

Let us take, first, the influence of funders. The priorities laid down for researchers by funding agencies influence the choice of the field to be studied and the planning and conduct of the individual steps of the project. The project has to make sense to the funders in order to be able to come into existence. And here is the paradox: some funders, particularly the EU under the various Framework Programmes, now prefer projects that have an element of international collaboration looking at the same topic. Therefore numerous academic teams based in multiple countries come together and ‘do’ comparisons. Very often, these comparisons are between nations (or more loosely, between practices situated in different places), but the sheer scale of EU funds often renders projects comparative on other axes as well. The availability of large-scale funding thus spurs a new kind of comparison which very often does not have its main purpose grounded in research problems. At least as often, such comparisons are driven by the political need of the EU to make sense of the EU as a ‘union’ of cultural practices and their internal differences. They are also driven by the fact that for large-scale research projects in the social sciences, ‘comparison’ is a convenient way of distributing and accounting for work. And finally, it is a way of making sense of individual subprojects of large-scale projects and claiming some kind of unifying theme of the work. It is unclear and has been barely analysed how such new forms of comparison relate to older formats. And, while earlier comparative practices, particularly in anthropology, tried to make sense of the ‘periphery’, the new EU funding regime looks at comparison to understand differences within the centre or to understand the relationship of centre and periphery.6 This has also brought a new form of relationship between centre and periphery: this new model of comparative research does not centralise comparative practice, but rather assigns each field site its own usually ‘local’ research team. In other words, we can observe a move from an anthropological comparative strategy, in which researchers are strangers, to a sociological one (see Stöckelová).

Second, comparative work hinges on the set-up and running of the comparator – the human and non-human entity that jointly produces comparison (see Deville et al.). Humans combine their sensory and organisational apparatuses with those of tools and machines. Comparators are unique too, and vary between each project. They are assembled in part in accordance with the funding proposal, which details the number of their human and nonhuman parts and outlines modality of their work, while their shape and specific formatting also changes as the projects progress.

It seems that the im/balance between humans and nonhumans within a comparator profoundly impacts the modus operandi of work and its results. This is most tangible when comparing (again!) the work of single human researchers to that undertaken by teams. The advantage of comparators including a single person is that much of the comparator is located in one person, and thus many of its decisions do not need to be made explicit during the research process. One person’s own intuition and preferences shape what is being researched and what lines of enquiry are being pursued. It is only when the comparator runs into problems, or when comparative research practice needs to be explained (as in academic texts), that the underlying assumptions of the comparator are made explicit.

Comparators that contain several persons face different kinds of opportunities and challenges. Most importantly, collaborative work tends to depend on making things explicit, and specifying and homogenising the comparator in far more detail. Therefore, assembling the comparator is a crucial element of comparison. Teams also choose different strategies for calibrating their comparators – allowing people, technologies, and other actors to adjust to each other and achieve ‘compatible’ ways of seeing and digesting data. This can include reading seminars, workshops, joint fieldwork, and so on. The scalar challenges of cross-national comparative projects, particularly favoured by large funding bodies, also increase the difficulties of making a comparator work (see Akrich and Rabeharisoa; Lutz; and Stöckelová, this volume). So too do the non-human parts of a comparator. All researchers also rely on a range of infrastructural tools to enable the conduct of their research. Luhmann was lost without his filing cabinet; ethnographic researchers would be lost without their notebook. Although tending to focus more on the natural sciences, STS has shown us repeatedly how such socio-material infrastructure can shape the conduct and outcomes of research. The fields themselves (and their various actors) also become part of the comparator and influence and shift our notion of comparison. This volume is full of accounts of how people and objects in the field change the course of comparative practice. And finally, the objects under examination possess different qualities to the researcher that make them comparable in different ways (see Faria, this volume).

If we think of the ways in which comparison is used, together with the various elements involved in practically doing comparison – beginning with the role of research funders, the internal set-up of the comparator and finally the role of the field itself – we can immediately see that the question of what is at stake when practising comparison cannot, and could never have been, whether comparison is good or bad, or whether it should be avoided. The question is rather which comparisons and which comparative infrastructures we want to implicate ourselves in, what we seek to understand with them, how we set up our comparator, and how we want it to relate to the field. There is no single, correct procedure for doing comparison, no correct answer to the question of what a good comparison is or should be. What the contributions to this book can do instead is to highlight some of their comparative decisions and selections, and some of the problems and conflicts that contributed towards comparisons being performed as they were.

Overview of the Book

The book is divided into three sections. The first, Logics, deals with how scholars of different disciplines conceive the rules of doing comparison. It offers an analysis of different objections and/or challenges to these rules, including situations where assumptions about comparison become a barrier to comparison itself.

When we speak about practising comparison, it is too easily forgotten that how we do comparison is guided to a great extent by books on method, methodological fashions, and previous comparative examples. A struggle common to all the contributions to the book is the very restricted ideas of comparison that exist amongst the imagery, methods, texts, and implicit rules of various disciplines.

The first two chapters take issue with such rules and constraints in very different ways. Monika Krause, in ‘Comparative Research: Beyond Linear-causal Explanation’, sets out to liberate comparison from its theory. She raises a charge: that comparative practice has suffered from an overly restrictive idea of comparison, one based on forms of ‘like with like comparisons’ drawn from ideas about linear causal explanation, with yet deeper roots in the randomised control trial. Measured against such standards, most comparisons of the social sciences fall short. Yet Krause maintains that social scientific comparison very often has quite different aims and that these should be conceived of according to different conceptual terms. She suggests that social scientific comparison instead often aims at better description, concept development, and critique, while providing explanations distinct from those of other disciplines. Such goals, then, imply the use of different kinds of comparison, ranging from what she calls ‘like with unlike comparisons’, to ‘asymmetrical comparisons’, to ‘hypothetical comparisons’, or to ‘undigested comparisons’.

Alice Santiago Faria takes a different route, trying to find a new logic of comparison from within a particular case. In her chapter, ‘Cross Comparison: Comparisons across Architectural Displays of Colonial Power’, she begins by analysing the logic of comparison in architectural history and theory. This logic, she maintains, is focused on comparing either buildings from the same building type, the same epoch, or the same style (typical ‘like with like comparisons’, in Krause’s parlance). Yet, drawing on her research on colonial architecture in Goa (India), she shows that focusing on the categories that guide architectural history does not illuminate the logic of colonial architecture. According to Faria, colonial architecture can be characterised as the display of power through the most prominent building type of a given epoch. This leads her to compare a Goan cathedral from the sixteenth century with a British-Indian train station from the nineteenth century. These buildings are radically different in terms of the traditional logic of architectural history: they come from different times, are built in different styles, and are different building types. Yet this apparent incommensurability comes to provide the very basis for a set of novel comparative movements.

The second section, titled Collaborations, deals with the various organisational, interactional, and political problems arising within collaborative research projects which are often strongly promoted by political donor entities, such as the EU. Project teams admit that collaboration can be laborious, as it brings unexpected challenges and twists when the imagined research ideas come to life and deal with incongruent realities of the field and diverse research practices across different academic traditions. It appears that the way the comparator (i.e. the entity that carries out the comparative work) is assembled and put to work determines what is and is not studied and put into mutual relation. In other words, collaborations shape the object of comparison just as the object shapes collaborations. This process involves endless adjustments or processes of calibration, through negotiations where hierarchies, personal relations, politics, and pragmatism co-produce the final end product – the outcome of research projects. Comparison is thus often not a singular act but a continual collaborative process undertaken throughout projects, from their inception as proposals to the process of analysis and writing.

In their chapter, ‘Same, Same but Different: Provoking Relations, Assembling the Comparator’, Deville, Guggenheim, and Hrdličková give a new meaning to the term comparator, as has already been described. Their chapter calls for more attention to be paid to the contingent practices in which the comparator becomes assembled, fed, and calibrated, as it determines how objects of study are approached, and continually interacted with. Such mutual interaction can provoke further comparisons and realign the comparator. Their auto-ethnographic narrative, about carrying out a seemingly conventional comparison of disaster preparedness practices across three countries (the UK, Switzerland, and India), tells how various unanticipated factors, such as varied levels of access, absences or presences of certain phenomena, made the comparator devise coping strategies and realign the whole outlook of the project. This leads to some interesting findings which would not have come to light had the conventional rules of comparing ‘like with like’ been strictly applied.

Madeleine Akrich and Vololona Rabeharisoa in ‘Pulling Oneself Out of the Traps of Comparison: An Autoethnography of a European Project’ recount the proceedings of their EU-funded project looking at patient organisations dealing with four different health conditions in four European countries. They concede that pragmatism was a guiding principle for the duration of the project. In the application stage, their research proposal was a strategic compromise between their intellectual interest in knowledge practices and the funder’s demands for an international/comparative/collaborative dimension. They thus deployed categories, narratives, and forms of reasoning which were not necessarily close to their interests, but that were crucial for obtaining the funding. Their comparative work thus did not result in typologies, as their research proposal might have suggested, but rather in multi-sited observations. Along the way they were producing and constantly calibrating comparators that would allow them to grasp singularities and commonalities, achieving a kind of common interpretive framework through sets of tools, instructions, and open discussions.

Reflecting on two of her research projects in the late 2000s – following women in science in five EU countries and the introduction of excellence frameworks in academia in the Czech Republic – Tereza Stöckelová’s chapter ‘Frame Against the Grain: Asymmetries, Interference, and the Politics of EU Comparison’ raises the important issue of the conventions and forms of politics that permeate contemporary comparative practices in the social sciences in Europe (and, likely, elsewhere). Drawing on her own experience, she finds that research designs often correspond and speak to the (pre)existing political realities, infrastructures, and imaginations that are defined by funders, invoking unhelpful categories and comparative practices; further, that this imagination is reinforced through the multiple, recurring executions of projects reproducing these specific frames, units, and asymmetries. In making a case for a more critical form of collaborative comparison, she argues for social scientists and funders to go against the grain and to commit to creating investigative frictions by not allowing prevailing notions to dominate.

The third section is Relations. As we have alluded to above, comparison inevitably involves the forging of new connections between objects, persons, and many other entities besides (e.g. concepts, discourses, feelings, places, cities, states, and so on and so forth). The contributions to this section each in their various ways explore the consequences of this comparative relationality. In particular, they examine the forms of relation within which researchers become implicated in and through the particularities of fieldwork, with an attention to how comparative practice becomes shaped by the objects of comparison, including by the sometimes explicit, sometimes more implicit, comparisons that these objects perform.

Christopher Gad and Casper Bruun Jensen’s paper on ‘Lateral Comparisons’ shifts authority for the production of comparison away from the social scientist to the field itself. Given that the field is densely populated with comparison, something a number of other contributors also note, they invite social scientists to allow themselves to travel on a journey with this existing and multifarious comparative endeavour in order to begin a process of ‘inventing around’ these practices. In outlining how this might be achieved, they focus on the comparisons that take place in and around a particular site: a Danish fishery inspection vessel. This involves paying attention to comparative relations that are put into play by both humans – notably the crew and fishing fleet inspectors – and a variety of non-humans, ranging from navigational aids to technologies that bring ships into direct comparative relation through monitoring activities. Practising comparison as a social scientist, then, is an act somewhere between a letting-go and a more active effort to resist the imposition of a layer of comparison on top of, and beyond, the various other, and often powerful, comparisons that are to be found once s/he starts looking.

This theme is taken up by Peter Lutz in ‘Comparative Tinkering with Care Moves’. Like Gad and Bruun Jensen, Lutz draws attention to the significance of comparative relations that already exist in the sites we study. In his case, this is senior home care and its movements and acts of transformation. A key point of difference between the two papers (one inevitably emerging from comparison!) is that Lutz also examines how such ‘found comparisons’, as one could call them, might (or might not) enter into productive relation with what might seem to be the more arbitrary comparisons that a social scientist might want to perform (and indeed ‘impose’). For Lutz, this is the attempt to bring together two sites that are spatially disconnected and organisationally and culturally quite distinct – senior home care in Sweden and the United States. Through a process that at once is reflexive about his own previous practice as a social scientist and takes the relations of comparison within field settings seriously, Lutz comes to advocate a process of comparative ‘tinkering’. This involves recognising the relational composition of comparison in-between the researcher and the researched and the ongoing adjustments that are required, as well as frictions that emerge, in the construction (and recognition) of comparison. One consequence of the tinkered comparison, he suggests, is to disturb some of the more conventional, standardised categories of comparison that are often rolled out uncritically within the social sciences.

In the next chapter, by Sarah de Rijcke, Iris Wallenburg, Paul Wouters, and Roland Bal (‘Comparing Comparisons: On Rankings and Accounting in Hospitals and Universities’), it becomes quite clear just what is at stake when some of these conventional categories of comparison begin to become deployed against the outputs of workers, including academic workers. Many readers of this book will already be experiencing the effects on their everyday practices of the increasing metricisation of academic outputs and, as a direct consequence, the rise of the comparative and competitive ranking of universities. By comparing ranking systems within Dutch universities to those used within hospitals, the paper examines just how such systems come into being, some of their performative effects, as well as, in a final ‘jump’ with parallels to Lutz’s approach, reflecting on how this particular comparative technology sits against their own comparative practice. This helps reveal how uncomfortable it can be to at once be situated as an object of comparison and an analyst of this objectification, as well as the centrality of commensuration to all comparative practices. As the authors suggest, such acts of commensuration can come into tension with a researcher’s desire (one common to STS researchers) to attend to empirical phenomena symmetrically.

Morgan Meyer, in the book’s final empirical chapter (‘Steve Jobs, Terrorists, Gentlemen, and Punks: Tracing the Strange Comparisons of Biohackers’), further pursues the tack of reflexively analysing his own comparative practices against those of his respondents, here ‘biohackers’. These are individuals, inspired by the ethics of hacking and open source, who seek to mess with biology in a wide variety of ways. Including in his own previous work, Meyer finds that, in trying to pin down just what biohacking is and what it aims to achieve, it is something of a trope to place its practices into comparative relation, whether it be to terrorists, Steve Jobs, or seventeenth-century gentleman amateurs (or to many others besides). The task Meyer takes on is to uncover exactly what these various comparisons do to biohacking and biohackers. What he uncovers are a series of frames that shape how ‘we’, as scholars, and ‘they’, as practitioners, understand those ‘yet-to-be-named transformative individuals working in biology’, as Meyer at points calls them (given that the very term biohacking operates in a particular comparative register). Comparison is shown to be a deeply value-laden operation, one routinely involved in the construction of social identities. At the same time, Meyer suggests that such problematics of comparison cannot simply be solved by better, denser, ‘thicker’ description. Instead, comparativists – if that’s what we (whether we like it or not) are – should be content to leave comparison as they find it, to allow it to exist in all its multiplicity and muddle.

The book ends with an Afterword by Jennifer Robinson, titled ‘Spaces of Comparison and Conceptualisation’. In it, she responds to some of the questions the essays raise. In navigating her way through these contributions, Robinson is drawn to asking after the spatialities of comparison, as part of an ambition to forge a revitalised comparative imagination. On the one hand, she argues, comparison is often thought/imagined/done in such a way as to reduce the spatial contingencies composition of that which is being compared (the case, the local, the city, the global, for instance). On the other, attending to spatial specificity (indeed, singularity) and to the way that such specificity can, in both theory and practice, enter into relation with an effectively infinite range of other entities, opens the door to comparative multiplicity. Here determining the ‘shared’ and ‘different’ registers of life and experience demands not a comparative universalism, but an approach to comparison that is modest and open to revision.

This suggests that practising comparison involves not a definitive fixing of the qualities of the world but a ‘holding steady’ just long enough for questions of difference and similarity to come into view. This requires considerable work to bring logics, collaborations, and relations together with comparative infrastructures, field sites, research teams, objects, and technologies, as well as the power dynamics that inevitably cross-cut them. Analysing exactly what is at stake in this endeavour is what we hope this volume will begin to achieve.

Notes

1 Using Google Ngram viewer. Percentage obtained by dividing total occurrence of terms (case insensitive) by the corresponding total occurrence of either the terms sociology/sociological or anthropology/anthropological (in order to control for an overall increase or decrease in the latter). 2008 is the most recently available data. A smoothing of 3 applied, using Ngram’s smoothing function. See original analysis at http://tinyurl.com/orgo9cs.

2 A similar analysis with IBISS, a database with journal articles, returns similar curves of ascendancy and fall, but with peaks for both disciplines roughly a decade later. Given the critiques around the authoritative production of knowledge we explore below, we are particularly keen to point out that we see these more as rough indicators of tendencies more than any definitive representation of trends. Far more work would need to be done to establish these tendencies firmly and authoritatively.

3 Concerns about comparison are of course not distributed evenly. Some countries’ anthropological and sociological traditions move forwards to a greater or less degree unconcerned by such attacks. George Steinmetz, for instance, argues that much US sociology ‘still seems to be operating according to a basically positivist framework, perhaps even a crypto-positivist one’ (Steinmetz 2005: 276). Beyond sociology and anthropology, the extent to which these challenges have been taken seriously within the social sciences varies considerably. Within cultural studies, cultural geography, and politics, particularly in parts of Europe, you may well find a similar situation. Venture, however, into economics, psychology, or – as Faria (this volume) explores – architecture departments, and the picture will be very different.

4 We might see forms of reduction as ‘abstractions’, in the terms outlined by the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead.

5 Research is also always the opposite, namely expansive, in the sense that each research project, each piece of writing, adds something to the world that wasn’t there before. Research inevitably does both: reducing the world to a selection of relevant terms and observations and expanding the world by adding to the existing set of ideas. Even the most ‘reductionist’ theory works against itself, since with its publication the world is not reduced but enlarged.

6 An overview of the latest round of FP7 (Framework Programme 7) research projects can be found here <http://cordis.europa.eu/fp7/ssh/project_en.html>, and those funded by the European Research Council can be found here <http://erc.europa.eu/erc-funded-projects>.

Bibliography

Bendix, R., ‘Concepts and Generalizations in Comparative Sociological Studies’, American Sociological Review, 28 (1963), 532–39

Boltanski, L., and L. Thévenot, De La Justification. Les Economies de La Grandeur (Paris: Gallimard, 1991)

Bryant, L. R., ‘Latour’s Principle of Irreduction’, Larval Subjects, 2013 <http://larvalsubjects.wordpress.com/2013/05/15/latours-principle-of-irreduction/> [accessed 18 August 2015]

Clifford, J., ‘Introduction: Partial Truths’, in J. Clifford, and G. E. Marcus, eds., Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), pp. 1–26

Clifford, J., and G. E. Marcus, eds., Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (Berkeley: University of California, 1986)

Cook, I. R., and K. Ward, ‘Relational Comparisons: The Assembling of Cleveland’s Waterfront Plan’, Urban Geography, 33 (2012), 774–95

Dickens, D. R., and A. Fontana, Postmodernism and Social Inquiry (New York: Guilford Press, 1994)

European Union, ‘Regulation (EU) No 1291/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 Establishing Horizon 2020 – the Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (2014–2020) and Repealing Decision No 1982/2006/Ec’, Official Journal of the European Union, L (2013), 14–172

Friedman, S. S., ‘Why Not Compare?’, in R. Felski, and S. S. Friedman, eds., Comparison: Theories, Approaches, Uses (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), pp. 34–45

Gingrich, A., and R. G. Fox, ‘Introduction’, in A. Gingrich, and R. G. Fox, eds., Anthropology, by Comparison (New York: Routledge, 2002), pp. 1–24

Halewood, M., A. N. Whitehead and Social Theory Tracing a Culture of Thought (London: Anthem Press, 2011)

Haraway, D., Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science (New York: Routledge, 1989)

Harding, S. G., The Science Question in Feminism (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986)

Jensen, C. B., ‘Comparative Relativism: Symposium on an Impossibility’, Common Knowledge, 17 (2011), 1–12

Keane, W., ‘Estrangement, Intimacy and the Objects of Anthropology’, in G. Steinmetz, ed., The Politics of Method in the Human Sciences: Positivism and Its Epistemological Others (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), pp. 59–85

Latour, B., An Inquiry into Modes of Existence: An Anthropology of the Moderns, C. Porter, trans. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013)

——Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005)

——The Pasteurization of France (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988).

Law, J., and J. Hassard, Actor Network Theory and After (Oxford; Malden, MA: Blackwell/Sociological Review, 1999)

Longxi, Z., ‘Crossroads, Distant Killing, and Translation: On the Ethics and Politics of Comparison’, in R. Felski, and S. S. Friedman, eds., Comparison: Theories, Approaches, Uses (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), pp. 46–63

McFarlane, C., and J. Robinson, ‘Introduction – Experiments in Comparative Urbanism’, Urban Geography, 33 (2012), 765–73

Peacock, J., ‘Action Comparison. Efforts towards a Global and Comparative yet Local and Active Anthropology’, in A. Gingrich, and R. G. Fox, eds., Anthropology, by Comparison (New York: Routledge, 2002), pp. 44–69

Radhakrishnan, R., ‘Why Compare?’, in R. Felski, and S. S. Friedman, eds., Comparison: Theories, Approaches, Uses (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), pp. 15–33

Robinson, J., ‘Comparisons: Colonial or Cosmopolitan?’, Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 32 (2011), 125–40

Scheffer, T., and J. Niewöhner, eds., Thick Comparison: Reviving the Ethnographic Aspiration (Leiden; Boston, MA: Brill, 2010)

Steinmetz, G., ‘Odious Comparisons: Incommensurability, the Case Study, and “Small N’s” in Sociology’, Sociological Theory, 22 (2004), 371–400

——‘Scientific Authority and the Transition to Post-Fordism: The Plausibility of Positivism in U.S. Sociology since 1945’, in G. Steinmetz, ed., The Politics of Method in the Human Sciences: Positivism and Its Epistemological Others (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), pp. 275–323

Stengers, I., ‘Comparison as a Matter of Concern’, Common Knowledge, 17 (2011), 48–63

Strathern, M., Gender of the Gift (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988)

Tyler, S. A., ‘Post-Modern Ethnography: From Document of the Occult to Occult Document’, in J. Clifford, and G. E. Marcus, eds., Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), pp. 122–40

Ward, K., ‘Towards a Relational Comparative Approach to the Study of Cities’, Progress in Human Geography, 34 (2010), 471–87