5

Pulling Oneself Out of the Traps of Comparison: An Auto-ethnography of a European Project

Madeleine Akrich and Vololona Rabeharisoa

Prologue

A couple of months ago, Madeleine was invited to an academic workshop on patients’ organisations (POs) and health activists’ groups. Her talk was based on our three-year EU-funded research project called ‘European Patients’ Organisations in Knowledge Society’ (EPOKS). The project examined the variety of practices developed by POs to collect experiential knowledge and compare it with credentialed knowledge, and reflected on how these practices transform the governance of knowledge and the governance of health issues these POs deem relevant. In all, we looked at POs concerned with four specific conditions (rare diseases,1 Alzheimer’s disease, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and childbirth) in four countries (France, the UK, Ireland, and Portugal).

After Madeleine’s presentation, one participant raised three interrelated questions:

1) To what extent do conditions and/or national contexts determine POs’ behaviours and actions?

2) How can one measure POs’ successes and/or failures to change policies?

3) Are there general lessons to draw from our comparative project?

Madeleine confessed to Vololona that these questions came as a surprise. Indeed, she did not present EPOKS as a comparative project and did not mention the term ‘comparison’ at any time during her talk. In response to the participant’s questions, she emphasised the complex and dynamic interplay between different elements such as the characteristics of conditions which are at stake, and the nature of credentialed expertise on these conditions in various countries. She also added that these should not be considered as mere external factors determining POs’ activities, but rather elements which POs problematise throughout their activities. Moreover, she stressed the fact that what we were primarily interested in was diversity. This included the diversity of knowledge that POs engage with, the diversity of their knowledge-related activities, and the diversity of the effects of their practices on research and health policies.

Hmmm… It is likely that our colleague was not entirely satisfied with Madeleine’s responses. This prompted us to ask ourselves the following questions: if we did not compare POs across the condition areas and national contexts we selected, then what exactly did we do? Why is it that we feel so uneasy with this issue of comparison? And how can we tackle this issue, given that it relates to the expectation that EU-funded projects should be comparative? To address these questions, we decided to revert back to our research practices and to the tools we set up for coordinating our project, extending from the writing of the research proposal to the drafting of scientific articles we submitted for publication. Our hope is that this retrospective auto-ethnography, based on a chronological retrieval of how and what we did, will clarify our approach to comparison, not only for our colleagues but also for ourselves.

Introduction

Why did we decide to apply to the EU call and to engage in such a multi-sited piece of research?2 Our motives stemmed from previous research done on POs, as well as from the ongoing dialogue we have sustained with them for more than fifteen years. Firstly, Vololona and Michel Callon investigated why and how the French Association against Myopathies (AFM) got involved in biomedical research and came to consider research as a privileged route towards the social integration of people with neuromuscular diseases (Rabeharisoa and Callon 1999). They undertook this research at a time when very few STS scholars paid attention to patients’ engagement in the production and dissemination of biomedical knowledge.3 Vololona and Michel were repeatedly confronted by colleagues who emphasised the exceptionality of the AFM, its wealth, and the fact that neuromuscular diseases mostly affect children and are thus likely to provoke empathy in the general population. However, they intuitively felt that this engagement in biomedical research was not the preserve of the AFM, and they thus began to investigate other POs concerned with rare diseases. At almost the same time, Madeleine and our colleague Cécile Méadel began to study patients’ and activists’ electronic discussion lists. In reviewing their exchanges, they were able to witness patients’ and activists’ preoccupations with knowledge and, most importantly, the variety of knowledge that circulates through these lists (Akrich and Méadel 2002; 2007).

Secondly, throughout our research, we soon realised that POs were not happy about being passively studied. They put questions to us, raised issues we did not initially identify, and manifested their willingness to play an active part in our research endeavour. This was not always a comfortable exercise for us, but we learnt to translate their concerns into interesting research questions. This proved so worthwhile that we organised participatory conferences with them on various occasions in order to develop a collective and reflexive work that is attentive to our respective standpoints on the dynamics of patients’ and health activism (Akrich, Méadel, and Rabeharisoa 2009).

Drawing on our previous research findings and observations, we made the decision to apply to the EU call with the following hypothesis: we wanted to put to trial the idea that different POs today build epistemic capacities and share political concerns about knowledge (both through the species of knowledge they engage with and the knowledge-related activities they undertake), with the view that the effects of these activities on POs and on their environments are diverse. More specifically, we seized the opportunity presented by the EU call to extend our sites of observation in order to confirm or disconfirm that

1) it is not only large and wealthy POs that are interested in knowledge (small and poorly endowed POs are too);

2) POs are not exclusively engaged in biomedical research. For instance, it is worth noting that some are also engaged in knowledge about medical practices or social sciences in less spectacular ways.

To be honest, we were not fully aware of what this decision committed us to. Of course, we did know that we would soon be confronted with the issue of comparison. However, at no point did we think that our multi-sited approach would raise methodological and conceptual difficulties that largely exceed the challenge of cross-national coordination. Applying to the EU call sounded like a good compromise between our intellectual interests on the one hand, and imperatives to ‘internationalise’ research and fund our activities on the other. At the risk of appearing naive, we did not anticipate that it would highlight, or at least expose us to, the ‘national’ dimension of comparison. Nor did we realise that engaging in this kind of comparative work would convoke a whole range of research traditions and practices. Eventually, it seemed like ‘comparison’ had an agency of its own, popping up like a mischievous spirit throughout the project and forcing us to make multiple adjustments.4

This paper is about our multiple encounters with this mischievous spirit of comparison. Indeed, while we thought that the research methodology we put together enabled us to master the issue of comparison in ways that suited us, this issue often reappeared out of the blue at unexpected moments of the project, very much like an evil spirit in a fairy tale. Though troublesome, this mischievous spirit was not all destructive, as it continuously fuelled our reflection on what exactly the issue of comparison entailed, and forced us to take our reasoning to its conclusion. In what follows, this paper will attempt to put the reader in the situation we had to face, and to recreate the surprises, uncertainties, and destabilising events we were confronted with. This is why the following text is in narrative form, starting with the drafting of our research proposal, and ending with the completion of academic articles drawing on the resulting research.

To Compare or not to Compare? The Writing of an EU Research Proposal

EU project applicants are often confronted with one main injunction: to demonstrate that their project will not simply result in the juxtaposition of a number of national case studies, but will bring in something more from their ordered confrontation. Indeed, an EU research project is expected to display similarities and differences between cases, and to determine explanatory factors for these according to the tradition of international comparisons (see for example Ragin 1981; Hassenteufel 2005; or Stöckelova, this volume). In our proposal, we were hardly able to escape this discourse, stating that

[t]he provision of care and the organisation of health services greatly vary from one country to another, and sometimes result in divergent claims from nation-based organisations which are concerned with similar problems. Medical traditions are also diverse […] As a case in point, the prominence of psychoanalysis in French psychiatry does make a difference in the way mental illnesses have been thought about, and results in specific claims from French patient and family organisations. Another important factor pertains to how certain issues raised by patient, user, and civil society organisations are valued by society at large. Although cultural explanation should be handled cautiously, the absence of a Mad Pride movement in France, for instance, as compared to what happens in the UK (Crossley 2006), is a telling example of some sort of cultural difference between those two countries. Finally, the maturity of civil society organisations, as well as their official recognition as stakeholders alongside institutions do matter. [Our emphasis]

In this excerpt, we clearly listed a series of variables usually related to the so-called ‘national context’ as potential factors which may explain the differences between POs, even though they are concerned with the same condition. One may notice, however, our own embarrassment with such an explanation when we mentioned the existence of a Mad Pride movement in the UK, and the absence of such a thing in France. Besides, out of the seventy-two-page proposal, this short paragraph is the only one where we detailed what the ‘national context’ is (supposed to be). We did not mention these elements elsewhere, and, most importantly, we did not consider them as factors to be searched in the methodology part of our project. Why not?

Undoubtedly it is because we did not intend to compare POs and explain similarities and differences between their behaviours and actions. This is in light of three particular variables which the literature on POs points towards: their organisational features, the nature of the conditions they are concerned with, and the national contexts within which they evolve (Huyard 2009; Löfgren, de Leeuw, and Leahy 2011). Indeed, prior to our EPOKS project, we coordinated an EU-funded specific action called ‘Governance, Health and Medicine: Opening Dialogue between Social Scientists and Users’ (MEDUSE), which consisted of a participatory workshop on POs’ engagement with knowledge (Akrich et al. 2008). The dialogue with POs led us to two main statements:

1) POs, as organised entities, are irreducible to one another – each encounters its own problems and develops its own form of action to solve its problems.

2) Despite massive differences between POs in terms of their size, wealth, or proximity to biomedicine, they engage with strikingly similar, yet varied practices in regards to knowledge production and dissemination.

We were also struck by the discrepancy we observed between POs’ practices and prevailing understandings of their role. The effect of this is that POs’ involvement in knowledge-related activities is often ignored: a clear-cut separation between experts and laypeople continues to be maintained. This prompted us to publish a non-academic book based on testimonies gathered from a variety of organisations (Akrich, Méadel, and Rabeharisoa 2009). The book targeted biomedical practitioners and public health authorities, as well as POs themselves, highlighting the POs’ multifaceted engagement with knowledge.

The EPOKS project took on the same conviction and aimed to explore the ways POs’ knowledge-related activities emerge out of, and impact on, a complex and dynamic interplay between different elements. Some of these elements related to patients’ conditions, others to the nature of credentialed expertise on these conditions, while some related to the missions POs endow themselves with (but whose list we, as social scientists, did not know in advance). The reason is that these are a result of POs’ own analysis of which elements are relevant in their situations. As we explained in our proposal,

the ways patients’, users’ and civil society organisations and movements intervene in the production of knowledge are not only diverse, but depend on national contexts, the causes that these organisations and movements stand for, as well as the web of expertise and issues in which they participate. EPOKS aims at deepening the understanding of this contextualised character of lay organisations’ involvement in the co-production of knowledge, and its impact on health policy-making.

The way lay organisations are involved with the production and circulation of knowledge depends on the causes they intend to defend. These causes depend on the characteristics of their particular conditions, and on the course of collective actions that various actors develop and that they decide either to join, or react to. [Our emphasis]

Let us expand a bit on the term ‘depends on’ in these excerpts from our proposal, as it actually denotes two different meanings. The first points to the singularity of every phenomenon, as it is captured by popular expressions such as ‘It all depends’. It puts to the fore the fact that neither the actors nor we as social scientists can escape relativism. The second meaning is that every phenomenon is made of cascades of relations between heterogeneous elements, including those usually seen as exogenous factors, such as the provision of care in one given country. However, these relations do not predetermine the subsequent story, but rather result from the involvement and action of various actors. As social scientists, we should pay attention to the ways these relations are actively unfolded in the situations under study. This second meaning of ‘depends on’ points to ‘relat-ionism’, rather than to ‘relat-ivism’, the idea that ‘anything goes’. The reasoning is that actors always situate themselves and act from somewhere, and so do we as social scientists (Haraway 1988). Therefore, this dual meaning of ‘depends on’ is exactly what the paradoxical expression ‘comparative relativism’ (Common Knowledge 2011) puts into discussion.

That being said, as we will see in a moment, we continued to talk about comparison, national context, and even typology throughout our proposal. There were obviously strategic reasons for this: after all, we applied for EU funding! The question then is how to work out the tension between this cumbersome injunction to proceed to international comparison, and our conviction that there is no such thing as a national context ‘out there’ which externally determines POs’ behaviours and actions. Ultimately, it was through the design of our work plan that we tried to dissolve this tension. As will be shown, our work plan helped shift the focus of our analysis from comparison to multi-sited ethnography (Marcus 1995).

From Comparison to Multi-sited Ethnography

Our project not only targeted POs in different countries, it also selected POs concerned with different conditions. Our objective was to observe a variety of sites and to highlight the fact that diversity does not contradict the existence of a phenomenon which crosses over these diverse sites, namely the crucial role that knowledge comes to play in POs’ activities. Our approach stood on the opposite side of a comparative study of cases which share a number of controlled variables (i.e. POs’ organisational characteristics, conditions they are concerned with) in order to evaluate the role of exogenous factors (i.e. factors other than the controlled variables – for instance, national contexts). This is because we did not hypothesise that the horizons of national POs are strictly delimited by national borders. In fact, it was quite the contrary, as from the outset we planned to analyse the complex networks of which POs partake, especially their transnational dimension. One objective of the project was indeed to reflect on ‘Europeanisation from below’ (i.e. the involvement of POs in networks of exchange and cooperation with European sister organisations), as well as ‘Europeanisation from above’ (i.e. the influence exerted by European umbrella organisations on national POs).

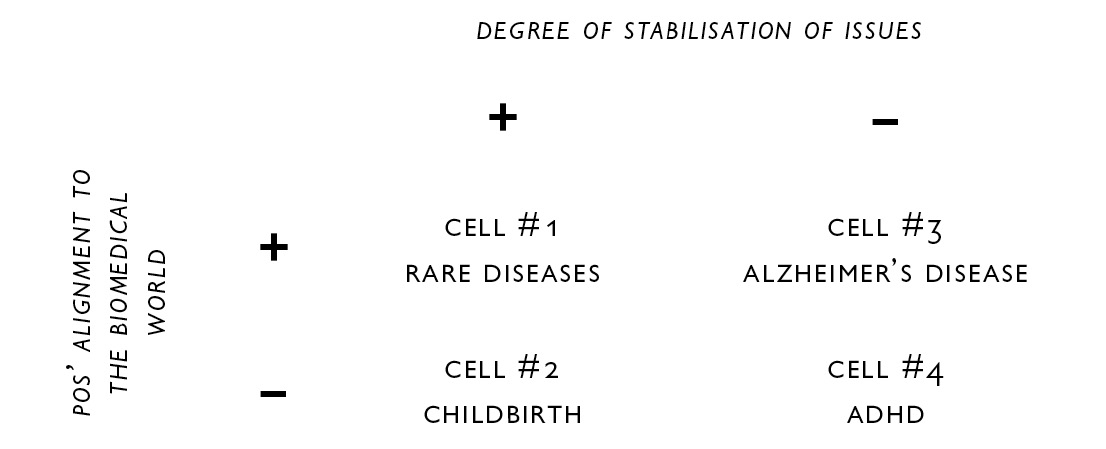

The final list of conditions that we decided to investigate was the result of discussions with colleagues we wanted to associate with in the research consortium, and all of these conditions intuitively seemed to be different enough to nurture the project. As mentioned previously, the list consisted of rare diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, ADHD, and childbirth. We were of course aware that reviewers might ask: ‘How did you choose these conditions?’, and that ‘intuition’ was not an appropriate answer to the question. To borrow from Becker’s motto: ‘What is this the case of?’ as recalled in Ragin (1992), we thus undertook rationalisation work in order to convince them, as well as ourselves, by addressing the question: ‘What were the conditions the cases of ?’ The typology we produced contrasted with the POs’ forms of engagement in knowledge according to two dimensions:

1) Their proximity/distance to biomedical knowledge and practices;

2) The degree of stabilisation of the network of expertise and issues related to their conditions.

We pictured and explained this typology as follows:

Table 5.1 Degree of stabilisation of issues vs. POs’ alignment to the biomedical world

Preliminary research and discussion among the partners of the present project suggest that each of these four organisations or movements may stand as an exemplum for each of the four cells charted above. Besides, for each of these four organisations, there are similarities as well as important differences from one country to another. National contexts do matter for understanding the dynamics of these organisations or movements, as well as their framing of expertise and issues. This is why we put cross-national comparison at the core of the present project.

One can easily sense how ambiguous such a typology is. Our primary intention was simply to plead for the importance of examining a variety of sites. However, the graphical chart we adopted, and the distribution of POs between the four cells of the chart, unavoidably suggest a classification. Though we were cautious enough in saying that this is a ‘proto-typology’ (our word), which may well be modified in light of our observations, typology cannot but suggest a kind of metrics for contrasting different situations. Interestingly, as soon as we began our fieldwork, we abandoned this proto-typology (see Section 2). Retrospectively, we assume that this had to do with our work plan, which left no room for such a typology to be actioned.

We designed our work plan as follows. First, we defined four work packages, each devoted to one of the four conditions we chose. Each package consisted of case studies of POs which were active on the same condition in different countries. The cross-national analysis so dear to the heart of EU officials was therefore embedded into the design of the four work packages (WPs). The four WPs obeyed the same pattern that comprised a detailed description of the data collection, including an analysis of the relationships POs might have with one another and with transnational coalitions. This delineated the process for collectively discussing POs within the same WP, and POs from different WPs:

It should be noted that, through their common involvement in common work packages, the partners will be constantly linked to each other all over the project, which is also a guarantee that the case studies will have a strong comparative dimension.

As one may expect, comparison was at the core of our work plan; however, it took up quite a different flavour here. First because we planned to establish a common interpretive framework for our observations, and second because all partner teams of the project were involved in different work packages and were invited to discuss collectively all case studies. Rather than contrast the different sites we studied, we decided to go through all of them and mobilise observations made on one site, as lenses through which to discuss what occurred in other sites. This is similar to what Henriette Langstrup and Brit Ross Winthereik (2008) did in their paper on the making of self-monitoring asthma patients in clinical trials and in general practices.

To recap, the writing of an EU research proposal comes with a very specific comparative injunction. That is, its aim is to find out similarities and differences between national case studies, and to explain how national contexts determine these similarities and differences. Unless one plans to proceed with such a comparative study, the writing of an EU research proposal rapidly turns into an equilibrium exercise. This is exactly what we experienced, as it involved constant navigation between the predicaments of comparison and alternative ways of looking at different sites. Retrospectively, it is clear, however, that we were not pursuing an international comparison which sought to explain differences and similarities through national contexts. Rather, we achieved this outcome by way of a transnational comparison (Hassenteufel 2005), which crossed various cases in order to bring more contrast and sharpness in the description of each, given that these cases are not supposed to belong to isolated planets.

Producing and Testing Comparators

However detailed it may be, a proposal is not sufficient to determine the actual conduct of a project. To study our different sites and to circulate amongst them, we had to refine constantly and transform our methodology. As Jörg Niewöhner and Philipp Scheffer (2008: 275) put it, the challenge was to ‘exceed both the single case study and the contrasting of any number of multiple cases’. It was then crucial to find a way to create a ‘rapport’ (Stengers 2011) between chosen POs and to look actively across them from a certain perspective. To borrow from Strathern (2011), we had to endorse a ‘perspectivist’ approach, which had a major practical consequence.5 More specifically, in the habitual meaning of ‘ethnography’, we did not proceed towards multiple ethnographies in different sites. Rather, we set up a series of tools and procedures for cutting across the different sites we selected with one perspective: to observe POs’ knowledge-related activities in light of the others’. To achieve this, we first went in depth into a common grid for data-gathering, and then we defined a protocol for discussing our observations in ways that each PO we studied (and/or partner team who studied it) served as a comparator to the others (Deville, Guggenheim, and Hrdličková 2013). Following Deville et al. (2013), we define a ‘comparator’ as the entity that does the work of comparison. In other words, the term ‘comparator’ designates one researcher, equipped with her/his embodied research experience, conceptual approach, and observations from fieldwork, and who puts her/his data and analysis to the trial of her/his project partners’. The comparator, therefore, is not a standard analyser out there; it emerges out of the comparative work it performs. In the following sections, we display the procedures we set up for turning not only each individual researcher, but also the project consortium itself, into a comparator.

The Making of a Common Gaze

How should we look at different sites to eventually produce a common interpretive framework? This was the purpose of the first meeting of the consortium (also called the ‘kick-off meeting’ in EU jargon), in February 2009. Though several partner teams had either an STS background or were sensitive to STS approaches, some also came from other disciplines, namely feminist studies, communication studies, and geography. Over the course of the meeting, however, we pragmatically put aside potential theoretical divergences. Our concern at this point was to define a shared protocol for data-gathering in ways that would permit us to look at the ‘same sorts of things’. As coordinators of the project, we suggested a common grid for fieldwork which comprised three parts: 1) historical backgrounds of POs; 2) knowledge-related activities of POs; and 3) specific examples. Each of these were divided into a description of the objectives and a description of the methods. As an illustration, we reproduce the second part below:

- Knowledge-related activities of POs

- Describe the PO/Civil Society Organisation (CSO) knowledge-related activities

- The PO/CSO’s role as co-producer of knowledge with specialists, as well as connector or translator between different worlds of expertise

- Its propensity to embrace or to challenge biomedical knowledge

- Content of information it produces (lay expertise versus experience-based expertise) and nature and scope of its targeted audiences

- Tools it mobilises for staging, shaping, circulating, and legitimating its expertise

- Participation in research projects and programs at national and European levels

Methods

- Collecting data through the PO/CSO website, publications (newsletter, brochures, leaflets, position paper if any), literature survey

- Identifying and interviewing key informants who are involved in knowledge-related activities6

This grid was clearly aimed at creating a common gaze on the POs we intended to study. It not only suggested how the fieldwork should be carried out, but also how to make it in ways that would later facilitate the crossing of our observations. This grid can therefore be a vehicle for circulating from one site to the next.

As science studies pointed out long ago, the manufacture of knowledge not only implies formal and explicit conventions, but also a shared culture resulting from repeated interactions between participants (Collins 1974; Knorr-Cetina 1981). We were soon reminded that social sciences do not make exceptions to the rule, especially when some partners raised questions about what exactly we meant by ‘knowledge’ and ‘knowledge-related activities’. Despite our initial attempt to ‘contain’ potential conceptual divergences on what should count as ‘knowledge’, as coordinators of the project we had to post a long note to all partner teams after the meeting in order to clarify the articulation between lay knowledge and formal knowledge:

METHODOLOGICAL NOTE:

HOW TO MAKE CHOICES FOR FIELDWORKAs promised, here is a note, which is supposed to clarify the way we should make choices regarding fieldwork.

In the oral presentation, we may not have put enough emphasis on a central point of the project: the articulation between lay knowledge and academic expertise (i.e. medical expertise, but also economic expertise, health technology assessment, and so on). To tell it very roughly, we are interested in situations where:

- Patients’ organisations try to push ‘lay knowledge’ in places where they are not normally considered relevant (i.e. in the determination of therapeutic strategies, in the elaboration of research programs or health policies, and so on).

- Patients’ organisations participate in the production of ‘expert knowledge’ in order to achieve a number of goals and to strengthen certain claims.

- We are therefore seeking cases where there is an effort to build connections between different forms of knowledge, different worlds, and where some ‘political issue’, whether at individual or collective level, is at stake. (Unpublished note, 10 March 2009: 1)

We also had to restate our approach to the fieldwork after some partners’ concerns with the use of ethnography. In the childbirth case for instance, we were really surprised at how similar knowledge-related activities exist within the five groups we studied, despite huge differences in their organisational features and initial motives for mobilising. That being said, the team which explored NCT UK recalled that the five groups are in fact very different. NCT UK, for instance, organises birth training sessions (which the other groups not do), and our colleagues who studied NCT UK suggested that it might be interesting at some point to do ethnography on the five groups. As coordinators of the project, we had to reassert that we did not intend to do ethnography on the POs, but rather to make observations that might help us to look at each of their knowledge practices in light of the others’. In the note mentioned above, we recommended that:

The word ‘ethnography’, which is used once in the project and has been used a few times in our meeting, should be taken in a very modest sense. ‘Observations’ should better describe what we mean: if any of us has for example, the opportunity to assist general assemblies, board of directors meetings, scientific committee meetings, official commissions meetings (organised by administrations or health organisations), it might be interesting to do it; to grasp the nature of arguments which are used by participants and evaluate the role of specific knowledge. But our approach is somehow heterogeneous and mainly pragmatic: we need to identify right places, relevant documentation, key informants in order to tell stories that will allow us to describe and analyse what is at stake around knowledge-related activities in each organisation, and in relation to their strategies towards various actors.7 [Our emphasis]

Retrospectively, despite the diversity of our backgrounds, we can fairly say that this recommendation played a crucial role in creating and maintaining a cohesive approach to our project. These notes certainly reinforced the creation of a common gaze on the sites we chose to explore. However, they achieved more than that: they settled down the premises of a common analytical frame by stating, for instance, that ‘the very nature of (POs’) self-help activities is not the focus of our research project’.

Most importantly, two elements from our research proposal, the proto-typology and the notion of national context, literally disappeared at this point. The vanishing of the proto-typology provides a clear indication of our approach to comparison. That is, we did not regard comparison as a classificatory method. Instead, we conceived comparison as a set of practices and tools for cutting across different sites with the same series of questions: what knowledge-related activities do POs undertake, for what purposes, and with what effects? Our ultimate aim was to test our hypothesis that knowledge indeed constitutes a strategic element of POs’ activism, however diverse they are. As for the notion of context, we can reasonably say that we did not consider it to be an analytical concept for explaining why and how knowledge does or does not matter. Rather, we proposed to our partners that they should embrace the perspective of POs and identify how they actively partake in the definition of the context in which they themselves intervene. However, these exclusions remained implicit, leaving room for some tensions between theoretical backgrounds and research practices to accumulate until they popped up in the form of questions raised by our partners. Ultimately, the practice of comparison seems to have an agency of its own, fuelled by many micro-differences not only in the objects compared, but also in the comparators themselves, thus following a more sinuous path than the one we tried to predetermine through our recommendations to our partners.

Working out Singularities and Commonalities

Fixing the modus operandi for fieldwork was not enough, of course, for we also had to reflect on the way we would concretely combine the outputs of the fieldwork. Communication, exchanges, and modes of discussion were extensively reworked all along the project, the organisation of each meeting being the occasion to reflect again and again on the kind of comparative work we wanted to undertake.

After the kick-off meeting and up to the July 2010 meeting, partner teams involved in each work package visited each other and/or exchanged emails to discuss the observations they made. They thus began to look at each PO focusing on one given condition (in light of POs concerned with the same condition in other countries).

The July 2010 meeting was conceived in order to extend this comparative exercise to all POs and all partner teams along the following procedures. Based on preliminary data reports circulated amongst partners, the first day of the meeting was devoted to presentations organised by work packages:

1) Firstly, according to the common grid we circulated, each team working on one given PO reported on the data it collected and gave a few suggestions on how to characterise the PO’s form of engagement with knowledge.

2) Secondly, those of us not involved in the work package (i.e. not concerned with the corresponding condition), were asked to display the similarities and differences s/he identified between the POs concerned with the same condition, and to bring in her/his views on these POs in light of what s/he observed in the case s/he studied.

3) Thirdly, a discussion took place where all partner teams commented on the analysis that emerged out of these presentations.

The second day of the meeting targeted the discussion of concepts, some of which drew on the literature, while others elaborated on the fieldwork to capture and make sense of the similarities and differences between the POs we studied.

Throughout this protocol, a dual process that put comparison at the heart of the research process was at stake: the objective was to ingrain the project as a ‘whole’ in the description of each case, as well to make the ‘whole’ emerge out of the diversity of cases. The expectation was that these repeated confrontations would produce a collective sensitivity to the specificities of each case, and that they would increase the relevance of our analysis on the common issue of the project (i.e. POs’ modes of engagement with knowledge and their meaning).

However, as already stated, comparison came into play with its own agency, sometimes de-structuring what we thought had been stabilised for a while. For example, take the two groups of parents of children with ADHD in France and Ireland. In our presentation of the French group, we insisted on the fact that parents are assembling various species of knowledge in order to provide a multidisciplinary approach to the disorder and its treatment. Moreover, we mentioned the group of parents’ contribution to the notion of cognitive disability, a category which is to be seen in the 2005 French Disability Act, but which does not exist in other countries. Our Irish partners also presented the variety of knowledge that the Irish National Council for ADHD Support Groups (INCADDS) and its member groups engage with. Although INCADDS embraces a biomedical definition for stating the fact of the disorder, it also pays attention to family therapies, as well as cognitive sciences and the promises of neurofeedback theory. It is most likely because of our focus on ‘cognitive disability’ as a French category that our colleague commented on the two presentations and was caught up with the question of the differences between the two groups. Almost automatically, the general discussion brought back the issue of ‘national context’ we thought we had neatly boxed as a manifestation of the ‘differential agency of comparison’. This led us to ask: ‘are there elements of these national contexts which may explain the differences between the two groups, and if yes, how do we account for these elements in our analysis’? It forced us to reopen the debate and to re-elaborate collective answers, which in this case translated into the idea that rather than talking of context, we should examine how each PO construes the disease.

Through the devices we progressively put in place over the project, we should say that instead of ‘doing comparison’ (i.e. comparing POs according a predetermined metrics that would be external to them), we were ‘making comparison’ (i.e. manufacturing comparators allowing to grasp from within POs’ singularities and commonalities) (Deville et al. this volume).

From Cases to Concepts, and Back

The closing session of the July 2010 meeting was devoted to discussing a series of concepts to make sense of the observations we made, and to delineate the significant features of the knowledge-related activities which patients’ organisations undertook, and which we planned to dig through over the coming months. As with any research project, our ultimate goal was indeed to publish, which implied that we had to disseminate our fieldwork to the space of academic production. This entailed another comparative endeavour, consisting of a twofold task: firstly, putting our case studies to the trial of relevant bodies of literature; and secondly, forging our own analytical tools to signpost how our approach might renew the understanding of patients’ activism.

The Academic Arena: Another Space of Comparison

Prior to the meeting, we circulated a list of concepts drawn from the literature. Some notions were coined by fellow researchers who investigated the upsurge of knowledge in the preoccupations of patients’ organisations. This, for instance, was the case for Steven Epstein’s ‘therapeutic activism’ (1995). Though very inspiring, this notion was too restrictive in regard to the variety of cases we examined, for it mainly targeted patients’ organisations which engaged in biomedical research and aimed at fostering the development of new therapeutics. Other concepts were proposed by scholars to capture the transformative effects of certain health movements. Maren Klawiter’s ‘disease regimes’ (2004) stood as an example, and raised much discussion amongst us. Some felt quite uneasy with this notion, due to the possibility that it might overshadow the multiple uncertainties in which certain conditions we explored were mired. Still, other concepts pointing to broad understandings of social changes were also on the list. This, for instance, was the case for the concept of medicalisation/de-medicalisation. We were pretty much cautious, however, about applying such an overarching concept to our fieldwork, for it might fail to account for the singular dynamic of each organisation we studied. Finally, we reflected on Sheila Jasanoff’s ‘civic epistemology’, which she defined as ‘the institutional practices by which members of a given society test knowledge claims used as a basis for making collective choices’ (2005: 255). Jasanoff coined this notion to explain the differences between the politics and policy of life sciences in the USA, the UK, and Germany. Though intended to serve a comparative purpose, this notion did not match the methodology we put together. Indeed, we did not look at the commonalities of patients’ organisations in one given country with an aim to compare these with the commonalities of patients’ organisations in another given country. Our project was at odds with such an approach: it rather insisted on the existence of numerous links between patients’ organisations of different countries, via European umbrella organisations, for instance, and questioned the circulation of models of activism between them.

To be sure, confronting our observations and epistemic orientations with those of other researchers is a classic academic game of sorts: colleagues expect you to consider previous studies on the same kind of empirical objects, and to discuss your analytical perspective in relation to existing ones. In retrospect, our playing of the game denotes two things. Firstly, we did it as yet another comparative trial extended to bodies of researchers/case studies we felt we were part and parcel of. Secondly, we did it to assert our collective agency by equipping ourselves with a shared reading of the literature. To strengthen this collective agency, we went a step further in elaborating a common interpretative framework grounded in our mutual understanding of the cases we studied and discussed.

Elaborating a Common Interpretative Framework

Our critical reading of existing concepts was motivated by our willingness to contribute something original to the understanding of patients’ activism. To achieve this, each of us was invited to propose descriptors which best translated what s/he observed and to question the others’ case studies in light of these descriptors. However, this collective production and discussion of descriptors did not occur in a conceptual void. As mentioned above, we balanced the merits and limits of existing notions in light of our fieldwork, paying extreme attention to how and what extent these notions captured the singularity of the situations we explored. For instance, in order to highlight patient organisations’ dual problematisation of what their conditions are, this prompted some of us to suggest moving from Klawiter’s concept of ‘disease regime’ to the notion of ‘cause regime,’ and what these conditions are the cause of (i.e. what sort of issues they bring in). Eventually, we dropped the very notion of ‘regime’, for it was too constraining in regard to the multifarious trajectories of patients’ organisations we studied. Instead of applying concepts from the outside, we were scrutinising if, and how, these concepts helped us to say something relevant about the specific issues which patients’ organisations gave shape to, and to which they brought about concrete solutions. As a way of illustration, one of us concluded our discussion on medicalisation/de-medicalisation as follows:

I feel like medicalisation/de-medicalisation is a highly situated issue […] We should consider it (medicalisation/de-medicalisation) as one PO’s concerns (amongst many others), rather than an analytical framework for us (EPOKS concepts 2009).

What then did our analytical framework look like? It articulated a series of descriptors of our own which enabled us to simultaneously dig around the similarities between the cases we studied, and to sharpen our attention to the specificities of each case. For instance, we clustered a series of descriptors under a common heading: ‘Cause – Singularisation/Generalisation – Politics of numbers – Recombinant science’. This allowed us to underlie a common feature of the POs we observed, such as the dynamic and joint transformation of their motives to mobilise and the networks of alliances of which they partake. Moreover, as illustrated by the following note, it also allowed us to highlight how each PO engages in this process:

Rare diseases patients’ organisations explicitly engage in ‘politics of numbers’ that they voice as follows: ‘Diseases are rare but rare diseases patients are numerous’ […] Recombining scientific knowledge constitutes another way to expand ‘causes’ […] By mobilising, combining and confronting various multidisciplinary bodies of scientific knowledge, some rare diseases POs, although concerned with very different diseases, come to identify potential transversal issues […] The French ADHD organisation recombines heterogeneous pieces of expertise and comes to ally with other collectives on this basis.

Now equipped with a common list of descriptors, each partner completed her/his study of POs’ knowledge-related activities and reported to the team seven months later, in February 2011. As coordinators, we hesitated quite a lot between two modes of organising this subsequent meeting, and asked ourselves ‘should we privilege conditions as entry points for presenting and debating our material, or the descriptors we put together’? We finally opted for the first option, fearing that the second one

… might constitute a too quick jump into a conceptual grid without paying enough attention to the specificities of each case, and lead to superficial exchanges [Our emphasis] (Email to the project team members, 16 December 2010).

We also envisioned parallel sessions, each on one given condition, but this did not prove feasible for each of us who were involved in different conditions. Furthermore, we explained to our colleagues that

[w]e need to consider that each condition is only an entry point into the discussion, but that depending on the issues raised, it should involve material and analysis from other work packages (Akrich, email to the project team members, 16 December 2010).

We stated over and over again our priority was to make sense of each case in its singularity, while immersing it into a common atmosphere created by our shared methodology and common descriptive language. Everyone played the game of comparing a few descriptors with specific knowledge-related activities that s/he studied. The descriptors which were the easiest to express through empirical data were the most successful, and allowed the integration of different case studies with a common interpretative framework. This was notably the case for our notion of ‘evidence-based activism’, which captured striking similarities in our observations (i.e. the fact that knowledge is not a mere resource but an object of enquiry for patients’ organisations, and that this affects their role in the governance of health issues in a variety of ways).

To recap, the process we went through was one of ‘constant comparison’ (Glaser and Strauss 1967) which took the form of a loop. The procedure started by travelling to each case individually, eventually returning to the original one with new lenses for augmenting its contrasts. The discussion about existing concepts and the production of original descriptors was embedded into this process, so much so that the group came up as an integrated comparator interlocking individuals, case studies, and notions. This has a crucial effect on the intellectual space we progressively designed: it is a space within which the analysis of each case is deepened through the circulation from one site to the next, thus suggesting a mode of generalisation which does not consist of extracting a few dimensions out of the singularity of each case, but rather thickens its singularity in light of the others. We will return to this point in our concluding remarks.

The Multiple Traps of Writing ‘Comparative’ Papers

After the February 2011 meeting, we decided to prepare a special issue of an academic journal on our notion of ‘evidence-based activism’, which appeared to encapsulate our findings the best. The issue was structured as follows:

1) An editorial recapitulating what we meant by ‘evidence-based activism’, and situating our notion vis-à-vis other concepts.

2) Four papers (one per condition) putting this notion to work and demonstrating how it renewed understanding of patients’ and health activism in these condition areas.

Doing and making fieldwork, brainstorming our cases, and playing around with concepts is one thing. However, writing academic articles is quite another matter. So far, we have deployed ourselves within spaces whose contours we carefully demarcated, and staged a methodology which permitted us to debate research questions in ways which suited us. When it came to writing papers, our previous efforts for putting things under control were dramatically challenged. Writing an academic article is of course highly constraining, if only because the authors are required to order empirical material, concepts, and arguments in a standardised 10,000-word-piece! In addition, however, we encountered a series of difficulties: some we anticipated, others we did not. In particular, the issue of ‘how to compare’, which we thought we sealed in our methodological and conceptual box, resurfaced like an evil spirit at different moments of the writing and revising process. How we faced this process is the purpose of this last section.

Structuring a Comparative Article and Facing the Evil Spirit of Comparison

As Hassenteufel (2005) rightly points out, writing a comparative article is a risky business. Either the author structures the article around a common interpretative framework and takes the risk of displaying the cases under comparison as mere illustrations of the concepts s/he puts forward, or the author details the cases s/he studies and concludes with a general discussion, an option which may undermine the comparative nature of the paper. We knew that we had to find our way through these two alternatives. What we were not fully aware of, however, was that the solution to this dilemma was very much dependent upon the number of cases we examined in each condition area, as manifested in the first version of our ‘childbirth’ paper (for which we investigated five activists’ groups in four countries).

In the introduction of our ‘childbirth’ paper, we reviewed the existing literature on childbirth activism in order to situate our approach (i.e. the fact that we concentrated on practices rather than on ideological discourses on de-medicalisation of childbirth, and that we especially investigated knowledge-related activities with an aim to reconsider childbirth activists’ groups’ positions vis-à-vis medicine). We then had four sections, each focusing on the national groups we studied, and on specific sets of knowledge-related activities that these groups developed:

1) Making normal birth an operative category: statistical evidence about practices as a coordination device in the UK.

2) Producing evidence and defining causes: putting surveys at the core of Irish activism.

3) From scientific evidence to matters of concern: CIANE’s participation in producing French guidelines.

4) International authoritative evidence as a source and a resource for the Portuguese childbirth movement.

Through this choice, we tried to hold together the internal coherence of each case and an analytical argument for the whole paper. The reviewers’ comments made us realise that pooling together a juxtaposition of case studies and a substantial demonstration proved to hold nothing! They were sensitive to our prevarications, and although they recommended that our paper was worth being revised, they also raised a number of criticisms. The first reviewer, for instance, could not perceive that each empirical case was intended to make a specific point, and said that (s)he did not know ‘how to work through the mountains of evidence presented to (him/her)’ (excerpt from the letter sent by the journal editor to the authors).

In addition to the structure of our articles, we were confronted with a serious burden related to being adamant that singularities matter. As the reviewer above confessed, s/he was lost in ‘the mountains of evidence’ we provided. How to make sense of ‘mountains of evidence’ without sampling, sorting out, and arranging them into categories? This question takes up a salient feature when writing comparative papers, for readers somehow expect to find out explanatory evidence of the differences and similarities between cases. This was where the issue of ‘how to compare’ reappeared like an evil spirit, not only in exchanges between us as co-authors, but also in some reviewers’ comments. Moreover, and this we did not fully foresee, it did so differently in each of the papers. Let us narrate how the evil spirit of comparison caught us, and how we pulled ourselves out of its traps in the three papers we co-authored.

The Trap of Typology

Because of the number of cases we studied – five groups in four countries – the ‘childbirth’ paper challenged us with the trap of typology. With five cases, one can hardly avoid typology readings, if only to ease the cognitive appropriation of the cases. In order to prevent such readings, we inserted quite a long discussion at the end of the first version, where the objective was to make sense of the differences between the cases (which any reader, even the most distracted one, could not miss), but without reifying explanatory factors of these differences. This puzzled the reviewers: the first found our paper too descriptive, whereas the second and the third read our piece as a preliminary step towards the elaboration of a typology that calls for further structural explanations, and they asked for more information on the organisations and countries. In effect, what we experienced was how difficult it is to report on multi-sited observations without inducing readings that escape the authors’ control. This is because multi-sited observations inevitably suggest readings either in terms of typology, or in terms of ‘global system-local situations’.

The solution we thus adopted was to revert to a more classic form of exposition: an articulation of the major claims in the introduction, an explicit and sustained argument in each part, the disentanglement of these arguments from specific case studies, and a clarification on the comparison issue. As we explained in our reply to the reviewers’ comments,

[t]he paper does not set out to undertake a comparison of the organisations or countries with a view to identifying variables that would explain their differences. It is now clearly signposted in the introduction that we focus instead on the capacity of the organisations to transform and redefine their environments by eliciting the emergence of new actors and new facts (Letter to the journal editor, 20 February 2013).

The Trap of the ‘Model’

With the ‘rare diseases’ paper which involved France and Portugal, we were caught in quite a different trap: that of the ‘cas d’école’ model, ‘golden event’ (Lévi-Strauss 1958). This stemmed from the fact that our previous research on the AFM led us to conclude that this organisation may be considered as a ‘cas d’école’ of partnership between patients and biomedical communities. Subsequent quantitative surveys and ethnographic fieldwork provided evidence on this ‘cas d’école’ being turned into a model that a large proportion of French rare diseases patients’ organisations, as well as the European Organisation on Rare Diseases (EURORDIS), endorsed. Because EURORDIS was very active in structuring umbrella organisations in Portugal, we confidently presumed that the French model of activism was disseminated in this country. Quite surprisingly, our quantitative and qualitative data disconfirmed our hypothesis: not only were Portuguese rare diseases patients’ organisations not as proactively engaged in biomedical research as their French sister organisations, but some were very critical of the notion of rareness, arguing that it did not do justice to patients’ and families’ real life problems, such as disability and social exclusion.

These findings considerably complicated the drafting of the first version of our paper. On the one hand we were, and still are, convinced that there is something peculiar to rareness. On the other hand, it was pretty clear that the ‘model of rareness activism’ which we initially had in mind took a serious hit! The initial version of our paper tried to play around this tension. This did not escape one of the reviewers, who criticised our methodological inconsistencies:

[The authors’] strategy of highlighting examples that contradict expectations is not the same as hypothesis testing.

Our mistake! After much discussion between the co-authors, we eventually decided to no longer posit the form of activism developed by French rare diseases patients’ organisations as a model against which we measure their Portuguese counterparts. Instead, we focused our article on how the very notion of rareness was problematised and transformed in the local sites it crossed. We also considered Portuguese organisations’ behaviours and actions as lenses through which to look back at French organisations, and, more fundamentally, questioned the very existence of a French model.

The Trap of ‘Comparing Comparison’

With the ‘ADHD’ paper, which involved one group of parents in France and one in Ireland, the concept of medicalisation resurfaced. Though we considered that this concept could not serve as an analytical framework for us after the February 2011 workshop, we did not clearly realise at that time that we could no longer rely upon this concept for ordering our comparative writing. However, because the literature on ADHD largely mobilises this concept, we put too much effort into arguing that our notion of ‘evidence-based activism’ better captures the two organisations’ epistemic efforts for extending and articulating a variety of evidence on the disorder (which go well beyond the realm of biomedical expertise). This was to such a degree that we did not find an intelligible way for highlighting how each organisation construed ADHD. Thus, as Stengers (2011) asserts, we were caught in the trap of ‘comparing comparisons’, and were too preoccupied with weighing the vices of the medicalisation frame on the one hand, and the virtues of ours in terms of ‘evidence-based activism’, on the other.

As we should have expected, it was precisely this issue of ‘comparing comparisons’ which the reviewers pointed out. They were all very enthusiastic about the richness of our empirical material, and just as much very critical of what they felt was an immoderate attack upon the concept of medicalisation. They suggested that we forced our empirical data into a restrictive analytical frame, and that somehow we were not fair enough in playing the game of ‘comparing comparisons’. Consequently, they raised the issue of how exactly we compared the two organisations, and asked whether the national contexts into which they evolved might explain their differences, which our demonstration left little room to do.

While revising the paper, much discussion arose amongst the co-authors on how to handle this issue of national contexts. Eventually, we developed a twofold argument:

1) That the two organisations are preoccupied with aligning their politics of illness (i.e. ADHD is a multidimensional disorder which needs a multimodal therapeutic approach) with their politics of knowledge (i.e. an interest in different species of credentialed expertise – biomedical, psychiatric, psychological, educational, etc.). Moreover, it appears that in order for this to be achieved, medicalisation is a starting point for the two organisations but not the end of the story.

2) That the two organisations’ politics of illness/knowledge aims to transform the network of experts and professionals they ally with/oppose, and that these alliances/oppositions themselves result from the ways the two organisations problematise patients’ and families’ specific situations.

Subsequently, the second version of our paper tried to tighten more than we did initially:

1) The comparison between our approach to ADHD activism and alternative understandings of the same phenomenon.

2) The comparison between the two cases we studied.

In retrospect, it is clear that putting together our special issue was yet another device: a very demanding one which forced us to provoke once more the issue of comparison and to sharpen our view on what exactly we ended up with. Of course, the writing of academic articles is always a trial, if only because reviewers have their own embodied epistemic perspectives and political agendas which the authors may not share. The comments we got from the reviewers on the first drafts of our papers also reopened our comparative toolkit and brought back the question: how to compare without explaining differences and similarities between cases from the outside? As a matter-of-fact, reviewers’ criticisms, as well as discussions between the co-authors over the writing and revising process, epitomised the ‘differential agency of comparison’, which manifested itself in a variety of ways and at different moments from the start to the end of our project. We faced the cumbersome injunction for international comparison, which we strived to get rid of in our proposal to the EU call. We fixed our methodological and conceptual approach to comparison and did the work accordingly. When the time came to write and revise our articles, we were overwhelmed by questions we thought we had mastered: what to do with national contexts? How to pull ourselves out of the traps of picturing the situations we examined as elements of a typology, or models of broader phenomena, or exceptions to well-established social theories? How to make sense of singularities which emerged out of our comparative approach without giving the impression of being too descriptive and lacking analytical depth? Those were the challenges which the evil spirit of comparison asked us to take up, and which led us to entirely rewrite the articles we submitted. Having gone through that process, we now feel (a bit) more comfortable with the questions Madeleine’s colleague raised in the beginning of this paper.

Conclusion

Recall that our colleague asked Madeleine about the general lessons we could draw on for our comparative research project. Comparison was indeed long considered as a surrogate experimental device for either revealing the general character of certain social phenomena, or for producing a model of the structure and functioning of society and its elements. The respective merits of quantitative and qualitative methods were fiercely debated: those who followed a positivist approach to society à la Durkheim embraced statistical methods, whereas those after Lévi-Strauss viewed society as a mechanics to be dissected and favoured case studies.8 Those debates on ‘variable-based’ versus ‘case-based’ comparison (Ragin 1981) have certainly evolved, but they have left two legacies: (1) that social sciences should overcome the singularity attached to case studies; and (2) that comparison is the methodology par excellence for elaborating and testing general causal explanations in social sciences.

The conception of comparison as a set of methods for generalising observations and research findings still looms large in many discourses, most notably in ones about EU research proposals. Explaining differences between national case studies by national contexts is the alpha and omega of EU comparative projects. For reasons related to our political agenda and our actor-network theory background, we did not go with this causal explanatory framework. Our contention was that whatever national contexts are, patients’ organisations display strikingly similar epistemic capacities for shaping health issues they deem relevant, transforming their environment for these issues to be considered at an individual and collective level. We were simultaneously very sensitive to the irreducible character of each organisation, and argued that patients’ organisations cannot be compared using a predefined exogenous metrics. This sounds like a catch-22: how to maintain that patients’ organisations are similar and yet irreducible? How to work out the ‘same but different’, as Deville et al. (this volume) nicely put it?

The methodology we staged aimed to handle this puzzle and propose an alternative approach to classic international comparisons. We progressively forged our consortium as a comparator: as a collective of individual researchers, case studies and concepts whose work was to make the situations we selected commensurable, i.e. searchable through the same set of research questions and procedures for data collection, and to augment contrasts within each situation in light of cross-examination and cross-interpretation of our observations. This way of comparing came with a radically different conception of generalisation: that is, generalisation in our research project was not a matter of ‘montée en généralité’ (Boltanski and Thévenot 1987), where case studies are abstracted from their idiosyncratic character. Rather, it was a matter of singularisation, which entailed shedding light on and making sense of how each patients’ organisation construed its cause and its context (Asdal and Moser 2012) in light of how other organisations do it. Our approach towards ‘how to compare’ and ‘what for’, attempts to put an end to the prevarications between sociology and history (Wievorka 1992; Passeron and Revel 2005). We neither built a social theory of patients’ organisations out of case-based comparison, nor did we celebrate the uniqueness of events which punctuate the history of each organisation. What we did instead was to highlight the existence of common practices amongst patients’ organisations, and to examine each organisation through the lenses of these practices. This eventually enabled us to pick out each organisation’s specificities, and to deepen understandings on their singular and original way of dealing with their own problems.

There are two additional issues which we would like to conclude with. One is the issue of how to measure patients’ organisations’ successes/failures in order to change policies. As it stands, this question does not resonate with our preoccupations, not because it is of no interest to us, but because it supposes the existence of a standard against which to evaluate successes/failures. Yet, we cannot compare ceteris paribus what happened before and what occurred after one patients’ organisation engaged in a condition-area, for patients’ intervention transformed the network of issues, problems, and actors at stake. It is the scope of these transformations and their effects that we should examine closely if we are to grasp the meaning of patients’ activism. Moreover, we suspect that this question of success and failure conveys another supposition, that certain national contexts are more conducive to patients’ and health activism than others. One commonplace thinking, for instance, is that within the EU certain countries are ‘advanced’ whereas others are ‘backward’ in respect to patients’ participation in health policies.9 Though tempting, such a supposition does not do justice to patients’ organisations’ transformative effects, including in the production of ideas on which countries are moving forward, and which ones are lagging behind in the condition areas they are concerned with. Our project also supported a more dynamic view on the ongoing construction of the EU by offering an alternative understanding of differences and similarities between its member states.

The last issue we would like to conclude with is the effect of our own comparative research project. From the outset, we were willing to act politically (i.e. to contribute something to the recognition of patients’ organisations as genuine actors in the domain of health and medicine), and not just as auxiliaries to traditional stakeholders (i.e. researchers, health institutions, political authorities, the industry), or as social movement organisations opposing traditional stakeholders. Our project certainly strengthened our political agenda: our data and analysis provided evidence on patients’ organisations’ active involvement in ‘collective enquiries’ which give shape to ‘publics and their problems’ (to borrow from Dewey [1927]), and helped us to argue that these POs’ practices are core to their activism. To convey the idea that patients’ organisations are legitimate experts on issues they raise, we organised a participative conference with social scientists, patients’ organisations, and stakeholders in the condition areas we studied. This conference took place in Lancaster in September 2011, and gathered about sixty participants. The epistemic-political message we transmitted over the conference was that whatever their specificities, all patients’ organisations have epistemic capacities: that is, they do not consider knowledge as mere resources for defending their causes, but as ‘things’ they are able to work around inventively and reflexively for transforming the politics and polity in their condition areas. This is what we actually meant by our notion of ‘evidence-based activism’, and this was diversely appreciated. Some patients feared that it echoed evidence-based policy and evidence-based medicine (EBM) too much, and may well have adverse effects in picturing patients’ organisations as insiders into research and political milieu. Others warmly welcomed our notion, arguing that it indeed offers a positive view on patients’ organisations as ‘knowledge-able’ (Felt 2013) and responsible actors who contribute something to society. So, one effect of our comparative project was to have extended dialogue (including with patients’ organisations) around the fact that despite their heterogeneity, they must be considered, and consider themselves, as full-fledged epistemic actors able to question the relevance and legitimacy of evidence onto which collective decisions are made. No doubt, we will continue to dig around this message, for it is what our comparative project enabled us to articulate.

Acknowledgements

The EPOKS project that we discuss in this article was funded by the European Commission FP7 (more information on the project is available on http://www.csi.ensmp.fr/WebCSI/EPOKSWebSite). We owe a lot to our research partners who contributed a creative and friendly atmosphere over the three-year duration of the project. We warmly thank the participants of the workshop organised by Joe Deville and Michael Guggenheim on this edited book, and who offered inspiring suggestions on a previous version of our article. We are particularly grateful to Joe Deville and Roland Bal for their thoughtful remarks. Our final thanks go to the members of Centre de sociologie de l’innovation of MINES ParisTech for their comments on the first draft of our article.

Notes

1 European legislation defines rare diseases as conditions that affect less than 1 out of every 2,000 people, or 5 out of every 10,000 people in a given area.

2 The EU call was funded by the ‘Science in Society’ initiative of the European Commission FP7.

3 There were notable exceptions such as Steven Epstein (1996), who studied HIV-Aids activism in the US, and Janine Barbot (2002) and Nicolas Dodier (2003), who studied HIV-Aids activism in France.

4 We warmly thank Joe Deville for suggesting this idea of an ‘agency of comparison’.

5 In her piece, Marilyn Strathern opposes ‘perspectivalism’ and ‘perspectivism’: ‘To be perspectivalist acts out Euro-American pluralism, ontologically grounded in one world and many viewpoints; whereas perspectivism implies an ontology of many worlds and one capacity to take a viewpoint’(2011: 92).

6 This grid is taken from Akrich and Rabeharisoa’s PowerPoint presentation at the EPOKS Kick-off Meeting, 24 February 2009.

7 We suggest adopting Isabelle Baszanger and Nicolas Dodier’s (1996) term ‘ethnographie combinatoire’ (combinatory ethnography), described as a process of selective collection of data/events which aims to account for situated activities that cannot be interpreted in terms of a unified set of normative references.

8 On those early debates about what comparison entails, see for instance the introduction to the special issue of Common Knowledge (2001) provocatively titled: ‘Comparative Relativism. Symposium on an Impossibility’. See also Niewöhner and Scheffer (2008) and Krause (this volume).

9 On these ‘development rankings’ of EU Member States, see also Teresa Stöckelova’s paper in this volume.

Bibliography

Akrich, M., et al., The Dynamics of Patient Organizations in Europe (Paris: Presses de l’Ecole des Mines, 2008)

Akrich, M., C., Méadel, and V. Rabeharisoa, Se mobiliser pour la santé. Des associations de patients témoignent (Paris: Presses de l’Ecole des Mines, 2009)

Akrich, M., and C. Méadel, ‘Prendre ses médicaments/prendre la parole: Les usages des médicaments par les patients dans les listes de discussion électroniques’, Sciences Sociales & Santé, 20.1 (2002), 89–116

——‘De l’interaction à l’engagement: Les collectifs électroniques, nouveaux militants de la santé’, Hermès, 47 (2007), 145–53

Akrich, M., and V. Rabeharisoa, ‘EPOKS Kick-off Meeting’, PowerPoint presentation at EPOKS kick-off meeting, 2009

Asdal, K., and I. Moser, ‘Experiments in Context and Contexting’, Science, Technology, & Human Values, 37.4 (2012), 291–306

Barbot, J., Les malades en mouvements: La médecine et la science à l’épreuve du sida (Paris: Balland, 2002)

Boltanski, L., and L. Thévenot, De la justification: les economies de la grandeur (Paris: Gallimard, 1991)

Collins, H. M., ‘The TEA Set: Tacit Knowledge and Scientific Networks’, Science Studies, 4 (1974), 165–86

Deville, J., M. Guggenheim, and Z. Hrdličková, ‘Same, Same but Different: Provoking Relations, Assembling the Comparator’, Working Paper 1 for Centre for the Study of Invention & Social Process (CSISP), Goldsmiths, University of London, 2013

——‘Same, Same but Different: Provoking Relations, Assembling the Comparator’, this volume

Dewey, J., The Public and Problems (New York: Holt, 1927)

Dodier, N., Leçons politiques de l’épidémie de sida (Paris: EHESS, 2003)

Dodier, N., and I. Baszanger, ‘Totalisation et altérité dans l’enquête ethnographique’, Revue Française de Sociologie, XXXVIII (1997), 37–66

Epstein, S., ‘The Construction of Lay Expertise: AIDS Activism and the Forging of Credibility in the Reform of Clinical Trials’, Science, Technology, & Human Values, 20 (1995), 408–37

——Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge (Berkeley: University Press of California, 1996)

Felt, U., ‘Innovation-driven Futures and Knowledge-able Citizens’, Lecture given at Science and Society – Meet with Excellence series, Department of Science and Technology Studies, Vienna, 2013

Glaser, B. G., and A. L. Strauss, The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1967)

Haraway, D., ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies, 14.3 (1988), 575–99

Hassenteufel, P., ‘De la comparaison internationale à la comparaison transnationale: Les déplacements de la construction d’objets comparatifs en matière de politiques publiques’, Revue Française de Science Politique, 55.1 (2005), 113–32

Huyard, C., ‘Who Rules Rare Diseases Associations? A Framework to Understand their Action’, Sociology of Health and Illness, 31.7 (2009), 979–93

Jasanoff, S., Designs on Nature: Science and Democracy in Europe and the United States (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2005)

Jensen, C., ‘Comparative Relativism: A Symposium on an Impossibility’, Common Knowledge, 17.1 (2011), 1–12

Klawiter, M., ‘Breast Cancer in Two Regimes: The Impact of Social Movements on Illness Experience’, Sociology of Health and Illness, 26 (2004), 845–74

Knorr-Cetina, K., The Manufacture of Knowledge – An Essay on the Constructivist and Contextual Nature of Science (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1981)

Krause, M., ‘Comparative Research: Beyond Linear-causal Explanation’, this volume

Langstrup, H., and B. Ross Winthereik, ‘The Making of Self-monitoring Asthma Patients: Mending a Split Reality with Comparative Ethnography’, Comparative Sociology, 7.3 (2008), 362–86

Lévi-Strauss, C., Anthropologie Structurale (Paris: Plon, 1958)

Löfgren, H., E. de Leeuw, and M. Leahy, eds., Democratizing Health: Consumer Groups in the Policy Process (Northampton: Edward Elgar, 2011)

Marcus, G. E., ‘Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography’, Annual Review of Anthropology, 24 (1995), 95–117

Niewöhner, J., and T. Scheffer, ‘Comparative Sociology: Introduction’, Comparative Sociology, 7.3 (2008), 273–85

Passeron, J. C., and J. Revel, eds., Penser par cas (Paris: Éditions de l’EHESS, 2005)

Rabeharisoa, V., and M. Callon, Le pouvoir des malades: L’association française contre les myopathies & la recherche (Paris: Presses de l’École des mines, 1999)

Ragin, C. C., ‘Comparative Sociology and the Comparative Method’, Comparative Sociology, 22.1 (1981), 102–20

——‘Introduction: Cases of “What is a case?”’, in C. C. Ragin and H. S. Becker, eds., What is a Case? Exploring the Foundations of Social Inquiry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 1–18

Stengers, I., ‘Comparison as a Matter of Concern’, Common Knowledge, 17.1 (2011), 48–63

Strathern, M., ‘Binary License’, Common Knowledge, 17.1 (2011), 87–103

Stöckelová, T., ‘Frame against the Grain: Asymmetries, Interference and the Politics of EU Comparison’, this volume

Wievorka, M., ‘Cases Studies: History or Sociology’, in C. C. Ragin & H. S. Becker, eds., What is a Case? Exploring the Foundations of Social Inquiry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 1–18