1

The Deplantationocene: Listening to yeasts and rejecting the plantation worldview

Denis Chartier

Fermentation processes are energetic phenomena which change the vibratory state of the environments which are subject to them and, when it comes to wine, those who drink it. All of this energy produces organoleptic emotions and sensations of wellbeing when we drink ‘real’ wine. In our modern age, in which people consume an increasing number of dead and disguised products which distance them from their fundamental nature and affect their intelligence and their looks, ‘real’ wine is a vibratory source which helps people find alignment within themselves, with others and with the environment (Philippe Pacalet, natural wine-maker).

Listen

Make yourself comfortable and put some headphones on if you can. Let’s begin with a journey through sound, scale and time. What you are about to listen to is a composition of the sounds produced by the microorganisms which produce so-called natural wine in the wine-makers’ vat (see Figure 1.1).1

Fig. 1.1 Yeast recording system (Clos du Tue Bœuf, Les Montils, France, September 2018)

This piece is the first part of a longer composition (Origins 2019) created for an art installation called L’Assemblée, made with vine stocks which were dug up after dying from fungal diseases. The aim of this piece was to create awareness of the complex but specific relationship that natural wine-makers have with the living world and to render this relationship perceptible. You will hear the juxtaposition of different parts of the fermentation process: Saccharomyces cerevisae (and other yeasts) transforming sugar into alcohol, Lauconostoc Oenos (and other bacteria) transforming malic acid into lactic acid (and perhaps others still). If I may, I will ask you to let these sounds sink in for a moment before you return to the text.

Scan the QR code (see Figure 1.2) with a smartphone or use the HTML link below to be transported to the Yeast Symphony (https://soundcloud.com/chartier-denis/yeastsymphony).

Fig. 1.2 Yeast Symphony (QR code)

Recordings from a vat of conventional wine-making fermentation2 would produce sounds which would probably be difficult to differentiate from those you have just heard. However, hours of recording and listening to the song of these microorganisms, enhanced by hours of observing the relationship between them and the wine-makers, have led me to track these talkative cracking sounds with a discerning ear. I suggest that we can hear agricultural practices which are gentler than those of conventional wine-making, more attentive to the cultivated environment, more respectful of the soil and of the existence of non-human creatures (the plants, microorganisms, fauna and flora present in the vineyard). What we hear is the result of an attempt at cohabitation, collaboration between humans and non-humans, rather than an attempt to coerce the living world or a relationship of domination. What we hear is a hymn to Orpheus, rather than to Prometheus: a hymn which involves listening to the living world to understand its secrets, rather than dominating it to force it to reveal things to us. What we hear is the materialisation of an ‘Orphic political ecology’ (Chartier 2016) in which yeasts, these beautiful symbiotes,3 are the main actors. What we hear is the promise of these microbes. Yes, the promise: because the care given to the yeasts in these vats is the embodiment of an attempt to break with the notion of monoculture which has shaped our tastes, our emotions and the modern era’s relationship with living creatures, as the concept of the Plantationocene developed by Haraway, Tsing and Gilbert so powerfully captures (Haraway and Tsing 2019). The plantation consists in the reproduction ad infinitum of a single species of plant, requiring other life forms to be neutralised or killed with herbicides and pesticides. But these French natural wine-makers are engaged in a break (insofar as is possible) with the practices of the plantation. They are trying to take us out of the Plantationocene by becoming actors of the Deplantationocene.4

So, there we have it. Everything has already been said, but now I must explain myself. To grasp this process of ‘Deplantationocenisation’, I will proceed in stages. First, I will demonstrate the extent to which vitiviniculture is an agribusiness which is organised around a naturalised vision of the plantation (ecological simplification, discipline of plants and humans, etc.) as a condition for managing nature. This sector has not escaped the global reproduction of a plantation economy. I then focus on natural wine-makers’ choices concerning vinification to reveal their very specific relationship with microorganisms and to show how, by means of a chain reaction, this relationship leads them to question the aesthetics of repetition, the standardisation of plants, the nature of the wines we drink, the ways of ensuring cohabitation and control of the living world, consumer tastes and the violence to which the inhabitants of these areas are subjected (Ferdinand 2019). This should help us to understand how they encourage us to abandon the plantation by inviting us to dream and to interact with living creatures other than humans.

Vitiviniculture and the Plantationocene

The history of vineyards and wine is so ancient that it is conflated with the history of humanity (Dion 2010; Ulin and Black 2013) or, at any rate, the history of Western society which laid the foundations for the Capitalocene (Moore 2015) and the Plantationocene. It is significant to analyse this economy, these pruned vines and the yeasts which make this beverage – which Brives (2017) reminds us, were among the first organisms to have been domesticated by humans. La vigne (vine) is an iconic ‘natureculture’ (Haraway 2016), as vineyards and wine have long been important economic and cultural elements within Mediterranean societies, and as such subject to processes of Plantationocenisation: they have become plantations like any other, reconfiguring the landscape and exploiting the living world and its share of pathogens. Because of the ecological simplification of the plantation and the increased transport of living materials from one continent to another (Tsing 2017), wine-making plantations have provided ideal conditions for the development of diseases and other animal ‘pests’.

The stereotypical image of fields of vineyards as a monotonous sea of stumps, stretching as far as the eye can see, is a recent reality and the result of the rise of monoculture vineyards, particularly at the end of the nineteenth century. The trend toward monospecific plantations intensified in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, although the speed at which it was adopted depended on whether the wine-making region had a long history of polyculture agriculture. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, French viticulture had entered a period of frenzied production. Low quality wines were preferred and there was no hesitation when it came to replacing traditional grape varieties with more productive varieties. Production in France rose from 30 million hectolitres in 1788 to 40 million in 1829, 70 million in 1870 and 85 million in 1875 (Dion 2010). Increased production subsequently led to the spread of diseases, primarily from the Americas, into French vineyards. Sparganothis pileriana, a vine-eating moth, arrived in the 1830s, closely followed by other microorganisms. Grapevine powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator) arrived in the early 1850s, while grape downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola) spread from 1878. Various measures were taken each time to limit the damage, including the application of sulphur and hot water and Bordeaux mixture made with copper sulphate. However, grape phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae) could not be contained. This aphid is said to have arrived with a soldier returning from a French military operation in Mexico and established itself among the few American vines he planted in 1864 in the south of France.5 This is significant, given that the concept of the Plantationocene ‘re-establishes a historicity of global environmental changes which does not erase the colonial and enslaving foundations of globalisation’ (Ferdinand 2019: 84). In about thirty years, phylloxera spread across French vineyards (and to the rest of the world); despite major efforts, this led to the total destruction of the vines (which died within three years of infection). Billions of dead vine stocks were dug up and gradually replaced by insect-resistant plants from America onto which local grape varieties were grafted. Hence this aphid brought the world of the vineyard and the landscapes associated with these plantations into the Plantationocene. Following this, vines were replanted in straight rows, making it possible to use draught animals and then machines to work the land. Production, which had fallen in five years from 85 million hectolitres to 30 million in 1880, began to rise again, with an increasing focus on monoculture vineyards (Dion 2010).6

Today, the wine industry remains a key economic sector in France (even if there has been a decline in the area cultivated for wine-growing and in wine production over the last few decades). With nearly 50 million hectolitres produced in 2018, France is one of the world’s leading wine producers (global production stands at 292 million hectolitres annually). With 750,000 hectares of cultivated land, 10% of the world’s vineyards but just 3% of French agricultural land, the wine industry is France’s leading agricultural sector in terms of value and the second largest export sector with a turnover of 9.32 billion euros in 2018 (after aeronautics and before cosmetics).7 As an industry, it is extremely standardised and is governed by considerable legislation. Wine has become a regulated product like any other and many wine-makers try to stabilise production from one year to the next, in terms of volumes, taste and distribution methods. The vast majority of these wines are produced ‘conventionally’, as my interlocutors refer to viniculture that makes use of pesticides, fungicides and other inputs, even if there has been a significant increase in organic production in recent years, with 14% of French vineyards recognised as organic in 2019 compared to 5% in 2009 (Agence Bio 2020). Given that there is more to wine-making than how the grape is grown (organically or not), it is important to be aware that conventional wine-makers intervene significantly in the fermentation processes in the vats, where grape juice is transformed into wine, to ensure maximum control of the fermentation and the resultant taste and stability of the wine. Only one third of wine-makers vinify their wines (the majority have their wines vinified in co-operatives). In organic wine-making, these interventions can be significant, even if just over 40 inputs are authorised, compared to more than 600 in conventional wine-making (Pineau 2019). This is to say that even in organic conditions, the logics of the Plantationocene dictate the orientations of public institutions, research organisations, wine state services and consumer tastes (Smith et al. 2007).

In this sense, natural wines are more than ‘just’ organic wines. Their fermentation processes do not involve inputs and require minimal intervention, determining a whole chain of relationships and practices to the living world and the local landscape. There are only a handful of natural wine-makers in France, probably no more than 1,000 from a total of 85,000 vineyards, or approximately 1.5% of the French wine market.8 However, they are extremely visible and are rapidly growing in numbers. I have been conducting regular fieldwork in the Loire Valley since 2013. In 2017–2018, as part of the Vin/Vivants collective, this fieldwork focused more specifically on the estates of three wine-makers.9 Hervé Villemade has a 25-hectare estate, Thierry Puzelat, who now works with his daughters Zoé and Louise, owns 19.5 hectares and Noëlla Morantin’s estate spans 6 hectares. The first two inherited their parents’ conventional wine-making vineyards, before changing their wine-making practices to produce natural wines. Noëlla Morantin took over a biodynamic vineyard. In addition to the deep affinities that bind us, I chose these wine-makers because the question of withdrawing from the practices of the plantation has been at the heart of everything they have done for more than 20 years.

Choosing to make do with what the area’s inhabitants give us

In order for fermentation to take place, yeasts are needed, as Louis Pasteur demonstrated in his Etude sur le vin, which revolutionised wine-making and earned Pasteur the title of ‘the father of modern oenology’ (Pasteur 1866). In natural wine-making, the care given to these organisms is crucial and determines everything the wine-makers do, from the field to the cellar. The biggest difference between natural wine-makers and their organic wine-making colleagues lies in the vinification process, during which technical interventions are limited as much as possible. In most wine cellars, grape juice is pasteurised, the processes are sanitised and controlled with sulphites, and exogenous, laboratory-grown yeast species are added to ensure that the right species are at work in the vats.10 The list of interventions is long and includes a horde of technical terms: reverse osmosis, tangential filtration, flash pasteurisation, thermovinification and more. All these practices are disavowed in natural wine-making, during which it is said that ‘nothing is added and nothing is removed’. Natural wines are made using organic grapes and indigenous yeasts; the process involves hand-picking but does not involve any inputs, filtering or any techniques which are described by some wine-makers as brutal and traumatising for living creatures.11 Sulphites are not added before or during fermentation;12 however, some wine-makers use very low doses (30mg/l) before bottling and, occasionally, to prepare their starter.

This way of making wine with minimal intervention is very risky and requires an intense focus on microorganisms and the processes of the living world. These processes are highly unpredictable. As a result, natural wine-makers must work differently at every stage from growing the grapes in the fields to selling the wine. Most importantly, natural wine-makers must understand and listen to the yeasts and the microorganisms; their activities and their environment must be closely monitored because any mistake can result in multiple complications, including the development of undesirable yeasts. Different yeasts result in different fermentation processes and some, like the famous Brett (Brettanomyce), can make wines undrinkable. In the words of Noëlla Morantin:

Brett, […] I’ve found that in some of my wines, it was just horrible […] the yeast develops when […] the grape juice is cold… it’s incredibly resistant, it establishes itself gradually but consistently, it invades the environment, it ferments really well… and so, once it’s started… I promise you, your wine is dry […] there’s no problem with volatile acidity […] but it smells like shit […] Brett’s a killer, it destroys everything it finds, it just takes over.13

These words, which highlight the truly unique relationship between natural wine-makers and these yeasts, show how important it is to monitor what happens in the vat as well as the ambient temperatures at the time of harvest. This is crucial information when it comes to understanding which yeasts will flourish. It is understandable that conventional wine-makers, when trying to produce a wine with the same characteristics from one year to the next, prefer to use industrial yeasts which have been chosen for their fermentation properties and organoleptic impact – a practice which has intensified over the past 40 years (Carbonneau and Escudier 2017).

Shepherding Yeasts:

Accepting uncertainty

There are different approaches to the fermenting processes, involving various levels of painstaking intervention. Jacques Neauport, one of the first oenologists to have championed natural wines, encouraged ‘obsessiveness’. If sulphur is to be avoided, everything must be impeccably clean. Neauport often told new wine-makers that they should spend time working in a dairy or brewery to learn how to clean the equipment. He also recommended buying a microscope to monitor yeast. Many wine-makers follow his advice to reduce the uncertainty of additive-free fermentation by using microbiological analysis:

During the harvest, we become microbiologists: we look with a microscope to see which yeasts and bacteria are potentially present […], I think it’s good to know the direction you’re going in, to find out if there are already any issues or not […] You have a clearer idea of where you’re going.14

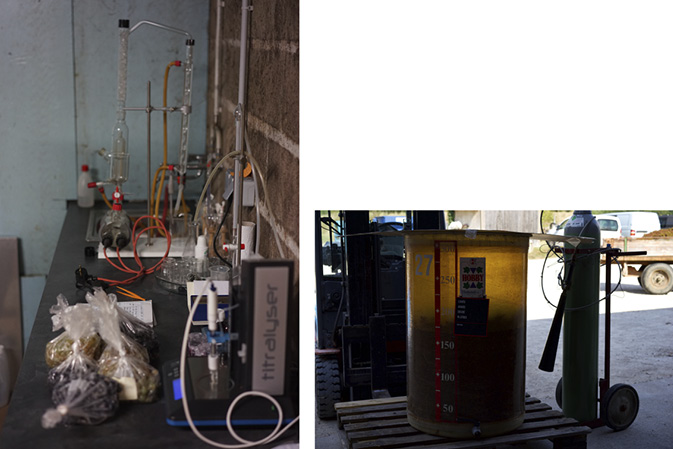

Fig. 1.3A, 1.3B Starter, testing system, and bags of grapes for testing (Hervé Villemade’s cellar, Celletes, France, September 2018)

Wine-makers are reassured to discover what they are working with and who they are talking to; they can also ensure that the right yeasts are developing by creating a starter (see Figures 1.3A and 1.3B). This operation, carried out just after harvest, involves using a small quantity of sulphites and heating a few dozen litres of grape juice to encourage the development of the desired indigenous yeasts and then introducing this into the vat containing the rest of the juice from the harvest.

As many people told us, testing usually confirms what the wine-makers’ own experience indicated during the fermenting processes. Wine-maker Jacques Neauport explains, ‘It takes ten years to start making natural wine properly, with ten years being the minimum period needed to understand every case, but even with years of experience, [a natural wine-maker is] always close to the edge’.15 Some people seem less worried than others about this ‘edge’ and have stopped carrying out these tests, having concluded that they did not leave enough room for wine-makers’ intuition or sensitivities, or even created unnecessary stress. The wine-maker Catherine Marin-Pestel, interviewed by Pineau (2019: 233), commented that she no longer tests her wines because it was like giving blood samples all the time to find out if she was ill when everything was, in fact, fine. In an interview, Didier Chaffardon noted:

I don’t know if we have sufficiently skilled laboratories for that. I’m not sure that it’s particularly useful, actually […] testing provides a kind of understanding which can restore confidence […] but that’s all […] you’ll never manage to contain the living world in a test or anything else […] testing will rarely be exhaustive […] on the other hand, intentions and trust are fundamental. If you don’t trust in the process, you can carry out all the tests you want […] the energy that you find in the wine won’t ever come from testing.16

At this stage, it is important to say that all the wine-makers we met told us that they listen to the yeasts fermenting in the vat, as you were asked to do at the beginning of this chapter. With a little experience, they are easily able to differentiate between the sound of alcoholic fermentation and the sound of malolactic fermentation, and they are able to identify the progress of the fermentation process by listening to various auditory characteristics in the vat (power, frequency of cracking sounds, etc.). This listening process is not in any wine-making manuals, but it is clearly a way to connect with the microorganisms at work in the vat on a daily basis.

For many of these wine-makers, their stance is driven by a sense of humility and a deep respect for the processes of the living world.

[…] The fermentation process is just incredible, it’s totally beyond us. […] There’s a whole world inside [the vat], all I try to do is to listen, smell and touch it, because the temperature is important… smelling it, listening to it, listening to the sound of the yeasts, etc., […]. I watch them just like a shepherd watches his flock. […] I talk about monitoring rather than controlling, because as I tell my trainee wine-makers, if there’s one verb you can remove from your vocabulary when you start producing natural wines, it’s the verb to control (Azzoni in Pineau 2018: 232–3, my translation).

Removing the verb ‘to control’ from a wine-maker’s vocabulary goes against the conventional concept of wine-making. Yet even if natural wine-makers are not entirely in control, they still produce excellent wines. This leads me to a crucial point: the focus on yeasts is not limited to what happens in the cellar. Didier Barrouillet, one of the first natural wine-makers I met in 2012, told me that as a former chemist, he had initially taken an interest in the vinification process before remarking that what happened in the vat depended on the quality of the grapes and the condition of the vine. His interest in these plants was inspired by a mantra known to many wine-makers, which Chaffardon summarises as: ‘when you’re generous with the vine, the vine is generous with everyone’. At the end of his career, however, he concluded that further work was necessary, including a focus on the soil. He came close to providing the definition of ‘terroir’ (the famous central concept when it comes to French wines) of Philippe Pacalet, a natural wine-maker from Bourgogne. A terroir is ‘a delicate relationship between mankind, the soil (pedology, microclimate, exposure), a vine plant and a climate. The link between it all is biomass: yeast and bacterial microflora’. It is well understood that viticultural practices, in turn, have a significant effect on terroir. Jules Chauvet,17 a major inspiration for these wine-makers, said as much as early as the 1950s when he advised against the use of herbicides, pesticides and chemical fertilisers, which ‘destabilise the life of the soil and our terroir… and render it impossible to make good wines’.

Fighting against monotony: Encouraging multispecies relationships to flourish

The yeasts found in the vat in early autumn are highly dependent on the yeasts found on the grape blooms in the fields in early spring. In order for these yeasts to be involved in the fermentation, organic practices must be implemented in the fields and a great deal of care given to the soil’s microorganisms and to the plants. Agro-ecological practices are adopted by these wine-makers to move away from a productivist, monocultural viticulture where forms of life other than the vine itself are neutralised with herbicides and pesticides. These wine-makers see other-than-human beings as allies, rather than enemies (Pineau 2019), with the maxim that a greater diversity of living things improves the chances of having healthy grapes, good yeasts and sufficient food for these yeasts during fermentation. For example, a significant level of nitrogen in the grape musts is crucial for the metabolism of the yeasts which will carry out the alcoholic fermentation. It ensures an excellent start to the fermentation process by promoting cell multiplication and encourages the yeasts’ metabolism to consume sugars during the process. In contrast, grape musts which lack nitrogen will lead to poor fermentation. In conventional agriculture, nitrogen can be added in different forms. This is not the case when it comes to natural wines. Wine-makers must therefore ensure that it is present in sufficient quantities in the fields and in the grapes. As Noëlla Morantin explains:

During vinification, I carry out several tests. When it comes out of the press, I take a sample on the same day and take it to the lab to find out how much nitrogen is in it, because if there’s enough nitrogen, you know that the fermentation process will be complete […] if there’s not enough nitrogen, it’s a nightmare […] we have to make sure that there’s enough nitrogen in the vines […] it’s pretty fascinating! So when people say that the vine makes the wine [slowing down for emphasis] you see what they mean […] and in the soil […] you see that’s right […] ensuring that your wine doesn’t lack anything means ensuring that the vine is in a good condition and not lacking nitrogen itself.18

It is clear that agricultural practices are instrumental here. To ensure a supply of nitrogen, some natural wine-makers focus on growing leguminous plants (lucerne, clover, vetch, etc.) to encourage nitrogen fixation. They break up the monotony of the plantation by introducing other plants between the rows of vines (see Figure 1.4).

Fig. 1.4 Biodiversity between rows (Hervé Villemade’s Vineyard, Celletes, France, July 2017)

Similarly, they plant between the vine rows to attract allies against predators (insects, birds, etc.). Some even hope to go further:

Because it’s humans who have created cultivated vines, which then become dependent. Then, to ensure that they continue to grow leaves and to produce fruit, you have to prune them and I find that really problematic. I’m considering lots of options, the shape of the vine when I prune it, something much less drastic, leaving more wood [… ]but that won’t necessarily work well […] Actually, I don’t know, I haven’t found an answer yet […] My goal is for the vines to become independent […] independent and wild […] just as I like to be [laughs] (Anne-Marie Lavaysse in Pineau 2017: 204, my translation).

The diversity of the living world and cohabitation with other non-human beings is cherished here, but it must not be essentialised. Viticulture is a complicated choreography involving human beings, soils, plants, microorganisms and the climate in areas which continue to be dominated by monoculture. Often, the relationship with certain microorganisms is similar to warfare, as some wine-makers told us during the mildew attacks in the Loire Valley in 2018.

To fight against mildew, organic farmers can only use copper, a heavy metal which can build up in the soil, leaving it infertile. It seems that well maintained, well fed, organic and diverse vines are more resistant to fungi (Deguine et al. 2016), but, in the Plantationocene, these fungi are becoming increasingly virulent because they are ‘cultivated’ in environments which benefit them (Haraway and Tsing 2019). This makes it increasingly difficult to fight them. These microbes, along with some animals which occasionally eat grapes and vine leaves, such as deer, are monitored and driven away or killed, in accordance with the practices which govern contemporary plantations, but with weapons which are often much less aggressive than those used in conventional plantations, the idea being to find other ways to fight or to cohabit, insofar as is possible.

Facing up to the monsters of the Plantationocene

The decision to work only with the microorganisms which are present in the soil heightens natural wine-makers’ awareness of environmental disruption and leaves them particularly exposed to disturbances and to ‘monsters’ (new pathogens, hybrid species) created by the Plantationocene (Tsing 2017). For example, some wine-makers told us that they struggled with the spotted wing drosophila (Drosophila susukii). This fly from Asia appeared in France in 2010 and is now present throughout France, where it has found new hosts. Like its European counterparts, it targets bunches of grapes, where it tends to inoculate acetic bacteria, which transform grape must into vinegar. When a plantation is affected, conventional wine-makers can pasteurise the must to kill any bacteria and re-sow with exogenous yeasts. This is not possible for natural wine-makers. Everything is intertwined.

They are also directly affected by climate change to such an extent that they are raising the alarm publicly, as sentinels. Thierry Puzelat explains:

My father only experienced a single black frost [a severe sub-zero episode] during his first year in 1945, and afterwards […] it froze 5, 6 times […] in 25 years, it’s frozen 10 times […] it’s become a more common occurrence with a significant shift in the 1990s […] the problem is that bud break and flowering happen earlier. Before, bud break began at the end of April, so no-one cared about the April frosts […] this year [2018], there were leaves on the vines at the end of March [… ]it’s not the spring frosts which have changed, it’s the time when bud break begins, because the winter is shorter. The problem that we have now is that we have hotter years and more sugar in the grapes; this makes vinification difficult and the wines are more difficult to drink, because they contain too much alcohol.19

This ever-changing situation is crucial when it comes to the development of their vineyards. ‘We are planting late grape varieties. Our parents had dug them up because they didn’t manage to bring them to maturity every year’. This also has an impact on their ability to make wine:

Claude Courtois [a renowned figure who has made natural wines for 30 years] says that everything is changing and that no-one understands it any more, particularly over the last two or three years! There are probably fundamental changes in the local microfauna and microflora and in a wider sense […] this has had a particularly disruptive effect on fermentation. He is mainly talking about red wine, it’s less noticeable when it comes to white wine but it’s true that things are changing…20

What is happening here is that the wine-makers are identifying a struggle, precisely because of the specific relationship they have with yeasts. Just as our human bodies struggle with the disappearance of symbiotic allies (Zimmer 2019), these wine-makers have seen that the terroir’s body is also struggling for the same reasons. A new microbiopolitics is emerging (Paxson 2018): it has been perfectly identified by wine-makers and leads them to quietly object to the expansion of the worldview of the plantation.

Drinking cloudy wine: living with the trouble21

Rejecting the worldview of the plantation when producing processed food makes it possible to step away from uniform tastes. For all the reasons mentioned here, the taste of these wines often differs from standardised conventional wines. They may be more acidic, more oxidised or more reduced than conventional wines. These ‘flaws’ often prevent them from being recognised as an appellation d’origine contrôlée (AOC)22 and there are endless debates as to what makes a wine ‘good’ and what makes it ‘flawed’. In some instances, this can end up in court, with natural wine-makers refusing to accept that their wines are not authorised for market.23 These wines still contain living microorganisms when they are bottled, and so they must be stored carefully because of the risk of microbial alterations which can make them undrinkable (continued fermentation, transformation into vinegar, etc.). Moreover, it is often said that it is better to drink a specific vintage at certain times of the year than at others, because it can be affected by lunar phases, for example.

These wines impose their own conditions in terms of how they should be stored and when they should be drunk: their sensitivity to atmospheric and astronomic changes has a significant effect on their taste. The vitality of these wines, which are produced by myriad relationships, dictates how they should be approached, how they should be drunk and how they should be sold. They are not sold by large retailers because they are too fragile and not sufficiently standardised. Instead, they are sold where they are produced or by a network of specialist sellers who provide explanations. Indeed, because they are rather bewildering when compared to conventional wines, an explanation about exactly what is being drunk needs to be provided to help novice drinkers fully appreciate these wines. One of the central tenets of the explanations about natural wines, offered almost systematically by wine-makers and wine merchants, is that these wines are made with genuine respect for the living world and are therefore a living product themselves. This argument is crucial when it comes to accepting a symbolic lack of clarity, which can sometimes be literal concerning these wines. They can become cloudy because the living microorganisms they contain may continue to develop, causing the wine to lose its clarity. What is normally seen as a flaw becomes a sign of vitality and of a drink which tells a different story to that of a deadly monoculture. Those who drink natural wines are also drinking an attempt to develop another story of multi-species cohabitation within the agricultural world.

Taking care of yeasts to reject the worldview of the plantation and vice-versa

These wine-makers reconnect with our microbial companions, developing relationships which are mindful of the interconnected worlds which these microbes impose. They fight against an ‘epidemic of absence’ (Velasquez-Manoff 2013) and a reduction in microbial exchange. Through their practices and their lives, they counter the ecological simplification of the plantation with an ecological complexification; they counter discipline with a form of wilderness, or rewilding, and they counter control of the living world with trust and relaxed detachment. By rejecting the practices of the plantation, they create trouble for the public institutions which govern French terroirs and orient consumer tastes. Rather than exhausting the soil, humans, plants and non-human creatures, they choose to feed, care for, nurture and protect them,24 guided by the microorganisms themselves.

Indeed, just as Stepanoff (2018) has shown that it is lichens which lead the reindeer and thus the Siberian ‘shepherds’, and just as Paxson (2018) has shown that cheese is the product of a multi-species collective which includes the sheep, the dogs which watch over them, the bacteria and the cheese-makers, making natural wine in the Capitalocene is a process which involves bringing microorganisms, plants and geological and climatic factors together, transcending the distinctions between biological and geological life (Povinelli 2016). Their actions are guided by the way the vine, the soil and the yeasts ‘respond’ to what they do. They talk about ‘soil’ as teeming with life and processes. They rely on chemistry and microbiology in addition to their knowledge of the principles of organic or biodynamic agriculture, and common sense which they develop over time. But they also rely significantly on their ‘feelings’ and what they hear and understand of the yeasts which ultimately guide their actions. In this way, they reject the worldview of the plantation, often quietly but tangibly, and they lead us in a subtle inter-species dance towards a Deplantationocene.

Notes

1 I made these recordings as part of a creative research project carried out in 2017–2018 with the Vin/Vivants collective made up of Emmanuelle Blanc, Aurélien Gabriel Cohen and myself. As a hybrid project combining humanities, visual arts and life sciences, Vins/Vivants intended to highlight responses to environmental disaster constituted by situated practices. Research was conducted in three vineyards belonging to Noëlla Morantin, Hervé Villemade and Thierry and Jean-Marie Puzelat (Clos du Tue Bœuf). It led to several exhibitions in France, including ‘Des Vivants, des Vins’ at the Scène National d’Orléans (January–March 2019).

2 The term ‘conventional wine-makers’ refers to wine-makers who control the life of the vineyard with a variety of toxic treatments to maintain a ‘healthy’ vine. They also intervene in fermentation processes, using numerous exogenous products to control them.

3 A symbiote is an organism which participates in a symbiosis, a long-lasting association between organisms of different species. Here, I use Haraway’s (2016) definition of symbiote, and not a strict ‘biological’ definition.

4 I would like to thank Emilia Sanabria for suggesting this term.

5 The objective of France’s intervention in Mexico (1861–1867) was to establish a political regime in the country which would be sympathetic to French interests.

6 Two of the wine-makers with whom we worked inherited their properties from their parents, who made the decision to transition from polyculture to monoculture in the 1950s and 1960s. Their children continued with this dynamic for a while, before recently returning to polyculture.

7 https://www.vinetsociete.fr/chiffres-cles [accessed 13 July 2020].

8 It is extremely difficult to provide an exact number, given that there are few natural wine-making associations or labels. However, work is currently ongoing to ensure the French government’s recognition of natural wines (Pineau, personal communication).

9 I also visited and discussed the wine-making process with other natural wine-makers, often working alone on small estates, to enhance my understanding of this practice.

10 There is an official catalogue of wine-making yeasts (384 in 2020) which wine-makers can choose from, depending on the fermentation and the type of wine they produce. These yeasts are not genetically modified organisms, as these are prohibited in France (unlike in the USA where GMO yeasts are approved by the Food and Drug Administration).

11 These are the terms used by a group of wine-makers who are trying to develop a natural wine charter as part of an association which was founded in 2019: Syndicat de Défense des Vins Nature’l (Proust 2019).

12 The first use of sulphites to make wine easier to store dates back to the eighteenth century and is said to have been invented by the Dutch (Carbonneau and Torregrosa 2020).

13 Interview, March 2018.

14 Morantin, March 2018.

15 laplumedanslevignoble.fr/2016/11/08/jacques-Neauport/ [accessed 6 July 2020]

16 Interview, December 2019.

17 Jules Chauvet is a wine-maker and biologist who studied fermentation from a chemist’s point of view in an attempt to remove chemistry from the process. See Pineau (2019) and Cohen (2013) on his role in the development of natural wines.

18 Interview, March 2018.

19 Interview, July 2017.

20 Chaffardon Interview, December 2019.

21 In French, this title is a pun on the word ‘trouble’ which means both confusion and a cloudy, murky quality, such as that of an unfiltered natural wine. Here, it echoes Haraway’s (2016) Staying with the Trouble.

22 An AOC is a product developed in accordance with recognised regional expertise that gives the product its characteristics and determines criteria, including agricultural practices and taste, which are required for it to be recognised as an AOC. Samples are blind tasted and approved or rejected by legislators who are often conventional wine-makers themselves.

23 Sébastien David, a wine-maker from Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil, lost his case against the French state and had to send 2,078 bottles of a 2019 vintage to a distillery; this wine was declared unfit for consumption due to its excessively high acidity.

24 I do not wish to stigmatise conventional wine-makers who love and care for their wine estates and the plants they grow in their own way, albeit in a context radically forged by the plantation (Haraway and Tsing 2019).

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Emmanuelle Blanc and Aurélien Gabriel Cohen for the inspiring Vin/Vivants collaboration and to Emilia Sanabria for her stimulating insights. My thanks also go to the sound artist Thomas Tilly for his precious advice which helped me enter more deeply into the world of sound recording, as well as to Jean Foyer with whom this research on natural wines began in 2013 and continued in the Institutionalising Agroecologies research programme. I am deeply grateful to all the wine-makers who shared their wonderful visions and ways of living.

References

Brives, C., ‘Que font les scientifiques lorsqu’ils ne sont pas naturalistes? Le cas des levuristes’, L’homme, 222 (2017), 35–56.

Carbonneau, A., and J.-L. Escudier, De l’œnologie à la viticulture (Paris: Editions Quae, 2017).

Carbonneau, A., and L. Torregrosa, Traité de la vigne, Physiologie, terroir, culture (Paris: Dunod, 2020).

Chartier, D., ‘Répondre à l’intrusion de Gaïa. Écologie politique orphique et gaïagraphie à l’ère Anthropocène’ (HDR Thesis, Université Paris 7 Denis Diderot, 2016).

Cohen, P., ‘The Artifice of Natural Wine: Jules Chauvet and the Reinvention of Vinification in Postwar France’, in Black R. E., and R. C. Ulin, eds, Wine and Culture: Vineyard to Glass (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), pp. 261–78.

Deguine, J.-P., and others, eds, Agroecological Crop Protection (London: Springer, 2017).

Dion, R., Histoire de la vigne et du vin en France. Des origines au XIXe siècle (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2010).

Ferdinand, M., Une écologie décoloniale (Paris: Seuil, 2019).

Haraway, D., Staying with the Trouble (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

Haraway, D., and A. Tsing, ‘Reflections on the Plantationocene’, Edge Effects Magazine, (2019) <https://edgeeffects.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/PlantationoceneReflections_Haraway_Tsing.pdf> [accessed 17 June 2020].

Moore, W. J., Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (New York: Verso, 2015).

Pasteur, L., Études sur le vin, ses maladies, causes qui les provoquent. Procédés nouveaux pour le conserver et pour le vieillir (Paris: Imprimerie impériale, 1866).

Povinelli, E., Geontologies. A Requiem to Late Liberalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

Proust, I., ‘Une nouvelle tentative pour définir les vins nature’, Vitisphère, <https://www.vitisphere.com/actualite-90880-Une-nouvelle-tentative-pour-definir-les-vins-natures.htm> [accessed 12 July 2020].

Paxson, H., ‘Post-Pasteurian Cultures. The Microbiopolitics of Raw-Milk Cheese in the United States’, Cultural Anthropology, 23.1 (2018), 15–47.

Pineau, C., ‘Anthropologie des vins “nature”. La réhabilitation du sensible’ (PhD thesis, EHESS Paris, 2017).

_______ La corne de vache et le microscope. Le vin ‘nature’, entre sciences, croyances et radicalités (Paris: La Découverte, 2019).

Tsing, L. A., The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017).

Ulin, R., and R. Black, Wine and Culture: Vineyard to Glass (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013).

Smith, A., J. Maillard, and O. Costa, Vin et politique. Bordeaux, la France, la mondialisation (Paris: Presses de Sciences Po, 2007).

Stepanoff, C., and J.-D. Vigne, eds, Hybrid Communities. Biosocial Approaches to Domestication and Other Trans-species Relationships (London: Routledge, 2018).

Velasquez-Manoff, M., An Epidemic of Absence. A New Way of Understanding Allergies and Autoimmune Diseases (New York: Scribner, 2013).

Zimmerer, A., ‘Collecter, cultiver, conserver les microbiotes intestinaux’, Écologie & Politique, 58 (2019), 135–50.