5

What is ‘good’ security? Categorising and evaluating encrypted messaging tools

Classifications and categorisations are, to put it in Bowker and Star’s (1999) words, ‘powerful technologies’, whose architecture is simultaneously informatic and moral and can become relatively invisible as they progressively stabilise, while at the same time not losing their power. Thus, categorisation systems should be acknowledged as a significant site of political, ethical and cultural work. Building upon the variety of different architectural and interface formats that we examined in the previous chapters, this chapter examines how this ‘work’ by actions of categorisation and classification happens in the field of encrypted messaging tools.1 We examine, as a case study, one of the most prominent and emblematic initiatives in this regard: the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s 2014 release of the Secure Messaging Scorecard. A particular focus is on the debates it sparked, and its subsequent re-evaluation and evolutions. We show how the different versions of the SMS, as they move from an approach centred on the tools and their technical features to one that gives priority to users and their contexts of use, actively participate in the co-shaping of specific definitions of privacy, security and encryption that put users at the core of the categorisation system and entrust them with new responsibilities, while at the same time, ultimately warning users that ‘we can’t give you a recommendation’ (Cardozo, Gebhart and Portnoy 2018). We also show how this shift corresponds to an evolving political economy of the secure messaging field: instead of a model of ‘one app to rule them all’, new approaches emerge, such as those mentioned in Chapter 4, that embrace the freedom of users to choose from or use simultaneously a multitude of apps, according to their social graphs and contexts.

The EFF Secure Messaging Scorecard: The shaping of a ‘community of practice’ through categorisation

For the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a digital rights group based in San Francisco, the question of what the most secure and usable tools are, in today’s diverse and crowded landscape of messaging systems, has been at the core of their advocacy work for several years. Their most prominent initiative in this regard has been the 2014 release of the Secure Messaging Scorecard (SMS),2 a seven-criteria evaluation of ‘usable security’ in messaging systems.

While the 2014 version of the SMS (1.0) displayed a number of apparently straightforward criteria – including, but not limited to, encryption of data in transit, ability to verify contacts’ identities, available documentation for security design assessment, and whether a code audit has happened in the recent past – our research shows that the selection and formulation of these criteria has been anything but linear.3 This was made particularly evident by the EFF’s 2016 move to update the SMS. Acknowledging that ‘Though all of those criteria are necessary for a tool to be secure, they can’t guarantee it; security is hard, and some aspects of it are hard to measure’, the foundation proceeded to announce that this was why it was working on ‘a new, updated, more nuanced format for the Secure Messaging Guide’.4

Indeed, in a digital world where, as Chapter 2 has shown, the words security and privacy are constantly mobilised with several different meanings – even within the same debates and by a priori alike actors, and even more so when profiles of needs and adversaries vary – it seems relevant, so as to shed light on yet another facet of the making of encryption, to take SMS’s first release as a case study. We can see its subsequent discussions and renegotiations as processes that destabilise, negotiate and possibly restabilise particular definitions of security, of defence against surveillance and of privacy protection. This chapter intends to show that initiatives such as the SMS and the negotiations around the categories that are meaningful to qualify and define encryption are in fact contributing to shape what makes a ‘good’ secure messaging application and what constitutes a ‘good’ measurement system for assessing (usable) security, able to take into account all the relevant aspects – not only technical but also social and economic. In addition to the fieldwork and interviews that are the basis for previous chapters of this book, the present chapter particularly relies on three in-depth interviews with current or past EFF personnel, conducted in November and December 2016. These are the person in charge of the first SMS (R1), the coordinator of the second SMS (R2) and the trainer and coordinator of the EFF Surveillance Self-Defense Guide (R3).

As Geoffrey Bowker and Susan Leigh Star remind us in their seminal work Sorting Things Out (1999), issues such as the origin of categorisation and classification systems, and the ways in which they shape the boundaries of the communities that use them, have been an important preoccupation for the social sciences in the last century. STS scholars in particular have explored these systems as tools that co-shape the environments or the infrastructures they seek to categorise and have addressed their particular status as both a ‘thing and an action’, having simultaneous material and symbolic dimensions (Bowker and Star 1999: 285–286). As this chapter will show, the EFF’s attempt to define an appropriate categorisation system for assessing the quality of secure messaging tools is indeed simultaneously a thing and an action, co-shaping the world it seeks to organise.

From an STS perspective, classification and categorisation processes are strictly linked to the shared perception different actors are able to have of themselves as belonging to a community. In many cases, these processes highlight the boundaries that exist between communities and constitute the terrain where they might either move closer or drift further apart:

Information technologies used to communicate across the boundaries of disparate communities […] These systems are always heterogeneous. Their ecology encompasses the formal and the informal, and the arrangements that are made to meet the needs of heterogeneous communities—some cooperative and some coercive (Bowker and Star 1999: 286).

Categorisation processes, as Goodwin (1996: 65) reminds us, are meant to ‘establish […] an orientation towards the world’, to construct shared meanings within larger organisational systems.

Borrowing from Cole (1996: 117), Bowker and Star point out that the categories produced by such processes are both conceptual (as they are resources for organising abstractions, returning patterns of action and change) and material (because they are inscribed, affixed to material artifacts). The act of using any kind of representation, from schematisation through to simplification, is a complex achievement, an ‘everyday, [yet] impossible action’ (Bowker and Star 1999: 294) that is, nevertheless, necessary to become part of a ‘community of practice’ (Lave and Wenger 1991), or in Becker’s words, a set of relations among people doing things together (Becker 1986). The community structure is constituted by ‘routines’ and ‘exceptions’ as identified by the categorisation system – the more the shared meaning of this system is stabilised among the members of the community, the more the community itself is stabilised as such:

Membership in a community of practice has as its sine qua non an increasing familiarity with the categories that apply to all of these. As the familiarity deepens, so does one’s perception of the object as strange or of the category itself as something new and different (Bowker and Star 1999: 294).

We will see how, in the highly unstable environment of the EFF’s initial attempt to categorise secure messaging tools with a view to providing guidance on their quality, the embryo of a community of practice started to emerge. At the same time, it went beyond – and revealed the manifold points of friction between – the relatively homogeneous group of cryptography developers, to include users of different expertise, trainers, civil liberties and ‘Internet freedom’ activists.

Classifications and categorisations, despite their embeddedness in working infrastructures and consequent relative invisibility, should be investigated as a significant site of political, ethical and cultural work (Bowker and Star ibid.: 319) – three aspects that our analysis of the SMS negotiations will unfold. In these three respects, categories are performative (Callon 2009): the reality of the everyday practices they subtend reveals that, far from being ‘enshrined […] in procedures and stabilized conventional principles that one merely needs to follow in order to succeed’ (Denis 2006: 12, our translation), they actively participate in the construction of the relation between the different actors that have a stake, or a role, in the categorised environment; categories, from this perspective, are one of the components of a complex network of actors and technologies.

The Secure Messaging Scorecard 1.0 and the unveiling of ‘actual security’

In November 2014, the EFF released its Secure Messaging Scorecard. The SMS was announced as the first step of an awareness campaign aimed at both companies and users – a tool that, while abstaining from formal endorsement of particular products, aimed to provide guidance and reliable indications that ‘projects (we)re on the right track’, in an increasingly complex landscape of self-labelled ‘secure messaging products’, in providing ‘actual […] security’.5 According to R1, ‘We tried to hit both audiences, we wanted to provide information for users and we also wanted to encourage tools to adopt more encryption to do things like release source code or undergo an audit’.

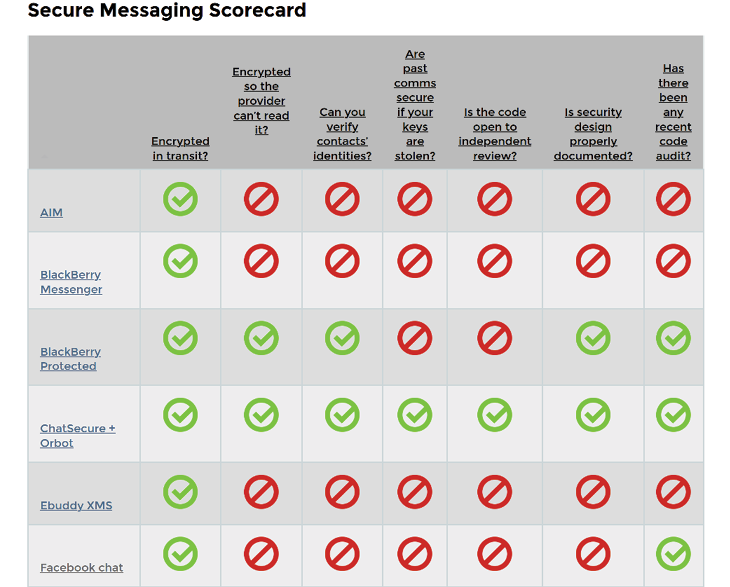

Fig. 5.1 The Secure Messaging Scorecard, version 1.0.

Overcoming the security vs usability trade-off

The EFF closely linked the SMS initiative to the Snowden revelations, mentioning that while privacy and security experts had repeatedly called on the public to adopt widespread encryption in recent years, Snowden’s whistleblowing on governments’ ‘grabbing up [of] communications transmitted in the clear’ has made widespread routine adoption of encrypting tools a matter of pressing urgency. R1 suggests that the need for such a tool came out of a need expressed by the general public:

It kind of came out of conversations at EFF […we] got a lot of queries with people asking which messaging tools they should use. So there have been a couple of projects in the past, like the guide ‘Who has your back’, a project that is a sort of scorecard of Terms of Service and how companies handle data, that’s where the idea came from… try to use the same approach to put information out there that we thought was useful about different messaging tools. (R1)

In the EFF’s view, adoption of encryption to such a wide extent ‘boils down to two things: security and usability’. It is necessary that both things go hand in hand, while in most instances, the EFF observes a trade-off between the two:

Most of the tools that are easy for the general public to use don’t rely on security best practices – including end-to-end encryption and open source code. Messaging tools that are really secure often aren’t easy to use; everyday users may have trouble installing the technology, verifying its authenticity, setting up an account, or may accidentally use it in ways that expose their communications (R1).

Citing collaborations with notable civil liberties organisations such as ProPublica and the Princeton University research Center on Information and Technology Policy, the EFF presents the SMS 1.0 as an examination of dozens of messaging technologies ‘with a large user base – and thus a great deal of sensitive user communication – in addition to smaller companies that are pioneering advanced security practices’, implicitly involving both established and emerging actors, with arguably very different levels of security and usability, in the effort. The visual appearance of the SMS is presented in Figure 5.1: a simple table listing specific tools vertically and the seven classification criteria horizontally. These are the following:6

1. Is your communication encrypted in transit?

2. Is your communication encrypted with a key the provider doesn’t have access to?

3. Can you independently verify your correspondent’s identity?

4. Are past communications secure if your keys are stolen?

5. Is the code open to independent review?

6. Is the crypto design well-documented?

7. Has there been an independent security audit?

The table includes intuitive symbology and colours to account for the presence or the lack of a requirement, and a filter giving the possibility of displaying only specific tools or getting a bird’s-eye-alphabetised-view of all the examined tools.

Thus, as we can see, the political and ‘quasi-philosophical’ rationale behind the SMS was clearly presented. It is interesting to acknowledge, in this context, that the ‘Methodology’ section in the presentation page was very matter of fact. It presented the final result of the categorisation and criteria selection process, but EFF provides very little information on the thought processes and negotiations that led to the selection. The page states, ‘Here are the criteria we looked at in assessing the security of various communication tools’, and proceeds to list them and the definitions used for the purpose of the exercise.

Yet, as researchers exploring the social and communicational dimensions of encryption from an STS perspective, we hypothesised that selecting and singling out these categories had been anything but linear, and that the backstage of these choices was important to explore – not merely to assess the effectiveness of the SMS, but also as a way of exploring the particular definition of encryption and security the EFF was inherently promoting at it was pushing the project forward. Indeed, it seemed to us that by fostering the SMS project, and due to its central role as an actor in the preservation of civil liberties on the Internet, the EFF was not merely acknowledging and trying to accumulate information about a ‘state of things’ in the field of encryption and security; rather, it was contributing to shaping the field, with the categories chosen to define ‘actual’ or ‘usable’ security being a very important part of co-producing it.

An ongoing reflection on the ‘making of’ the criteria

While the SMS’s main presentation page focused on the criteria in their final form, there were some indications of the EFF’s ongoing reflections on the ‘making of’ such criteria, and of their online presence. A post in early November 2014 by chief computer scientist Peter Eckersley, ‘What Makes a Good Security Audit?’, acknowledged that the foundation had ‘gotten a lot of questions about the auditing column in the Scorecard’ (Eckersley, 2014). Eckersley proceeded to explain that obtaining knowledge about how security software had been reviewed for ‘structural design problems and is being continuously audited for bugs and vulnerabilities in the code’ was deemed as an essential requirement, but it was also recognised that the quality and effectiveness of audits themselves could vary greatly and have significant security implications. This in turn, he suggested, opened up discussions that eventually led to the inclusion of three separate categories accounting for the process of code review (regular and external audits, publication of detailed design document and publication of source code) (Eckersley, 2014). Despite the fact that methodologies for code audit vary, Eckersley gave examples of fundamental vulnerabilities that a ‘good code audit’ may decrease. The code audit criteria thus refer to other systems of classifications, such as the CVE (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures), an international standard for Informational Security Vulnerability names.7 Other ‘Notes’ attached to some of the criteria are indicative of backstage negotiations, as they mention ‘compromises’ both on forward secrecy (encryption with ephemeral keys, routinely and permanently deleted after the communication, a ‘hybrid’ version of which is accepted ‘for this phase of the campaign’) and on the source code’s openness to independent review (‘only require[d] for the tool and not for the entire OS’).8

In parallel, musings on the SMS came from several actors in the encryption/security community at large. Some criticised the lack of hierarchy among the criteria, the phrasing of some of them and even the messaging tools’ alphabetical ranking.9 Others conducted alternative reviews of tools included in the SMS and questioned their quality, despite the fact that they had been scored positively on the EFF grid (Hodson and Jones 2016). Yet others concluded that the EFF was being ‘pushed to rethink’ the SMS (Zorz 2016). Indeed, relying on these documentary sources, it seems that reflections within the EFF on the quality of the SMS categories and their possible alternatives and evolutions, and, on the other, more or less constructive external criticisms of these same aspects, took place in parallel and paved the way for a subsequent version of the tool – all the while shaping ‘good’ security and ‘good’ encryption, as well as how users and developers could grasp what this meant.

In early August 2016, these reflections seemed to have reached a turning point as the EFF ‘archived’ its SMS main page, labelling it a ‘Version 1.0’, and announced it would be back in the near future with a new, improved and ‘more nuanced’ guide to encryption tools, explicitly referencing the ongoing revisions that had characterised and were still characterising their categorisation work: ‘Though all of those criteria are necessary for a tool to be secure, they can’t guarantee it; security is hard, and some aspects of it are hard to measure’ (Figure 5.2).10 It also anticipated that the term ‘scorecard’ would be dropped in favour of ‘guide’.

Fig. 5.2 Secure Messaging Scorecard main page between August 2016 and its withdrawal in 2018 (https://www.eff.org/secure-messaging-scorecard).

What did the first SMS do? Performativity and performance of a categorisation tool

And thus, Version 1.0 of the SMS was no more, except in the form of an archive preserved ‘for purely historical reasons’ of which the EFF itself discourages further use.11 Nonetheless, our interviews with EFF members and with security trainers in several European countries – as well as the fact that the EFF decided to leave the SMS visible to the public while putting it in context – demonstrate that the first SMS did a lot of things to and for the encryption and security community, and contributed to shaping the field itself.

Indeed, the first SMS appears to have had a performative effect on the community: the EFF has a central role as a protector of online civil liberties and setting up a scorecard in this field was a pioneering effort in its own right. In an otherwise mostly critical discussion thread among tech-savvy users,12 it was recognised as such (‘The EFF scoreboard carries the embryo idea of a global crypto discussion, review, comparison and knowledge site that could also serve as a great resource for non-crypto people and students to learn a lot about that field’), and most interestingly, it led the encryption technical community to be reflexive about itself and its own practices.

There were a number of reasons for this reflexivity. The first was because a ‘hybrid’ organisation – EFF includes some technical people but also individuals with a number of other profiles – spearheaded this effort (‘Isn’t it a bit strange that a small organisation of non-computer scientists produce something that was painfully missing for at least 50 years?’). The second was because it prompted reflection on parallel categorisation efforts that may better respond to what the technical community sees as ‘good security’. As one contributor put it:

The highly valued information you and other experts are dropping […] should be visible in a place that collects all that stuff and allows for open discussion of these things in the public, so people can learn to decide what security means for them. If such a thing exists, please show me. If not, please build it.

Indeed, by its very creation, the SMS caused a reaction in the developer community, making them wonder whether a categorisation effort of this kind was worthwhile, including the EFF’s particular efforts. Despite the flaws they saw in the scorecard, developers seemed to perceive EFF as a sort of standardising or trend-setting body; they knew that many users would rely on the SMS if they perceived it to be the advice of EFF, in part thanks to some of the other initiatives aimed at bridging technical soundness and user-friendliness, such as the ‘crypto usability’ prize.13

Interestingly, and despite the EFF’s announced intentions, we can retrace some early ambiguity and perhaps confusion about the SMS’s intended target audience. The simplicity and linearity of the grid, the symbols used, the way categories were presented – each of these aspects could indeed lead the encryption technical community to think that it was aimed at both developers and users (confirmed earlier by R1, as well), and perhaps primarily at users. However, there are other indications that it might have been the other way around – in which the primary target would be fostering good security practices among a wide number of developer teams, with usability being a subsequent target. According to R2,

what motivated us to make the scorecard, is to survey the landscape of secure messaging and to show developers: ‘look that’s what we think is important. So you should use all these things to make a truly secure tool’, and then we can get to the usability part.

And later, even more clearly:

Originally the target of the SMS was not users, telling users ‘you should use Signal or you should use something else’. […] It was… we were trying to make a grid so that developers could see ‘ok I need to get this and this to check all the boxes’. But it backfired….

So, it appears that one of the core things the SMS did was to prompt practices by end users that to some extent escaped the EFF team’s intentions and control: intended as an indicative checklist for developers, the SMS actually assumed the shape of an instruction tool for users and cryptography trainers – a ‘stabilised’ and defining artefact, when in fact it was anything but.

Ultimately, and despite the EFF’s warnings,14 developers appeared worried that the SMS and its set of criteria would appear to guidance-seeking users as a performance standard that tools should achieve in order to qualify as ‘good encryption’. Take, for instance, this comment by ‘tptacek’ on Hacker News:

Software security is a new field, cryptographic software security is an even newer field, and mainstream cryptographic messaging software is newer still. The problem with this flawed list is that it in effect makes endorsements. It’s better to have no criteria at all than a set that makes dangerously broken endorsements.15

This concern is echoed by EFF, with R2 pointing out during our interview how the organisation became worried about the SMS’s use as an endorsement, or a standard, especially by those users whose physical safety actually depends on the security of their communications – those user profiles we defined as ‘high risk’ in Chapter 1. Indeed, the effect of SMS 1.0 on ‘real life’, relating both to how it was engineered and presented, appears as one of the primary motivations to move towards a second version, as we will explore further in the following section of this chapter.

‘Security is hard to measure’: Revisiting the SMS, (re-) defining security

In the interviews we conducted with them, EFF members describe how, since the early days of the SMS’s first version, there had been an ongoing process of thinking back to the different categories. Taking into consideration what actors in the encryption community considered ‘errors’ (shortcomings, misleading presentations, approximations, problematic inferences), and revisiting their own doubts and the selection processes used during the making of 1.0, the EFF team started to analyse how the choice of these categories contributed towards building specific understandings of encryption and security. With this in mind, they started to consider how the categories could evolve – and with them, the definitions of ‘good encryption’ and ‘good security’ they presented/suggested to the world.

Questioning the grid: Incommensurability of criteria and the ‘empty tier’

A first, fundamental level at which the reflection took place concerned the choice of the format itself. The feedback on the first version of the SMS revealed that in the attempt to be of use to both developers and users, the scorecard might have ended up as problematic for both:

We got a lot of feedback from security researchers who thought that it was far too simplified and that it was making some tools look good because they have hit all the checkmarks even though they were not actually good tools. So we ended up in a little bit in between zone, where it was not really simple enough for end users to really understand it correctly, but it was also too simple from an engineering standpoint (R1).

But in the making of the second version, according to R2, they wanted ‘to make sure […] that we can put out something that we’re confident about, that is correct and is not going to confuse potential users’. Especially in light of the meanings that users bestowed upon SMS 1.0, a key question arose: was a grid the most useful and effective way to go? Perhaps the very idea of providing criteria or categories was not suitable in this regard; perhaps the updated project should not take the form of a grid, to avoid the impression of prescription or instruction to users that may previously have been given by ‘cutting up’ such a complex question into neat categories. As R2 explained, while discussing the possibility of creating a second version of the scorecard,

we are definitely abandoning the sort of grid of specific check boxes […] A table seems to present cold hard facts in this very specific way. It is very easy to be convinced and it’s very official […] we are definitely going towards something more organic in that way, something that can capture a lot more nuance. […] there’s a lot more that makes a good tool besides six checkmarks.

As both R1 and R2 suggest, we see how this intended additional ‘nuance’ was at some point being created not by eliminating categories, but by revisiting them. A suitable second version of the SMS may have divided the messaging tools in a set of different groups – R2 calls them ‘tiers’: the first group would include tools recommended unconditionally, whereas the last group would convey an ‘avoid at all costs’ message (e.g. for those tools that have no end-to-end encryption and present clear text on the wire). Within each group the tools would again be presented alphabetically, and not internally ranked; however, instead of visual checkmarks, each of them could be accompanied by a paragraph describing the tool in more detail, specifically aimed at users. As R2 comments, ‘this is essentially so that we can differentiate [between tools] … because we realize now that users are using this guide…’. And R1 suggests that it is also for the benefit of diverse user groups, with different levels of technical awareness: ‘the goal is for people who are looking on the scheme on a very high level [to] say these tools are the best, these are bad, and there will be a slightly more nuanced explanation for people who really want to read the whole thing’.

Interestingly, the EFF team declared to us in early 2017 that, if the tiered model was going to be used, there were plans to keep the first tier… empty. This had strong implications for the definition of good encryption and security, basically implying that an optimal state has not yet been achieved in the current reality of the secure messaging landscape, and as of yet, a mix of usability and strong security is still an ideal to struggle for. One of our interviewees, for instance, commented that there is currently no tool that provides sufficient levels of insurance against a state-level adversary. Interestingly, the feeling that a ‘perfect tool’ is lacking has found its graphical representation in drawings collected as part of our fieldwork (see Chapter 1, Figures 1.2, 1.3, 1.4). The new SMS would convey the message that nothing is actually 100% secure and make users aware of the fact that there is no ‘perfect tool’, yet it can still be recommended without reservation. R2 gave us practical examples of why the team came to this conclusion, citing WhatsApp’s practices of data sharing with Facebook (its parent company) or Signal’s reliability problems for customers outside the United States.

In passing, the EFF team was defining what, according to them, would ideally be a ‘perfect’ secure messaging tool: end-to-end encrypted, but also providing a satisfactory level of protection from the risks of metadata exploitation, which, as we saw in Chapter 1, is still the core theoretical and practical issue for the developers of secure messaging tools. The emptiness of the tier represented a strong message to begin with, but was of course bound to evolve:

If a tool got pretty close, and did not provide perfect protection against metadata analysis, we still might put it up in that tier and say look, these people have made a really strong effort […] But so far, it is going to be empty. Just to emphasize that there’s still plenty of distance for tools to go, even the best ones.

Thus, the EFF was not planning to skip its ‘recommender’ function which was at the core of the first version of the SMS; however, as we will see later in more detail, the focus was going to be placed on contexts of use and on the different ‘threat models’ of various user groups. Thus, weaknesses ‘may not be shown in a check-box’.

The graphic and spatial organisation of the second version of SMS was planned to radically differ from 1.0’s table. First of all, moving from a table to a list implies a different way of working with the information and undermines the idea of a direct, linear and quantified comparison offered by the table. A list of tiers with nuanced descriptions of different apps and their properties offers room for detailed and qualitative explanations, while tables tend to put different tools on the same surface, thus creating an illusion of commensurability and immediate quantified comparison. As R2 says: ‘It’s […] definitely not gonna be a table […] it will be more like a list: here is the first group, here’s the next group, here’s the next group, here’s the group you should never use’.

The idea of ‘filters’ adds a certain degree of user agency to the classification of tools: the lists become modulable as users may set up a criterion that could graphically reorganise data, providing cross-tier comparisons. This offers a different way of classifying the data and ‘making sense of it’, compared to a table. The latter is, as Jack Goody puts it, a graphically organised dataset with a structure that leaves little room for ambiguity, and as such becomes an instrument of governance (Goody 1979).

Another problem posed by the grid format, that the new version of the SMS sought to address, was the projected equivalence of the different criteria, from the open-source release of the code to its audit and the type of encryption. The ‘checklist’ and ‘points’ system created the impression of an artificial equality between these criteria, and therefore led to the idea that one can ‘quantify’ the security of a given tool by counting points. In fact, the presence of some criteria rather than others, or the degree to which they are implemented, may result in different impacts on security and privacy, in particular for users in high-risk contexts:

[If you were] someone who does not know anything about crypto or security, you would look at this scorecard and would say, any two tools that have, say, five out of seven checkmarks are probably about the same [while] if… one of those tools actually had end 2 end encryption and the other did not, even though they both had code audit or the code was available, or things like that, their security obviously isn’t the same. [The SMS 1.0] artificially made the apps that were definitely not secure in the same way look secure. And we were worried it was putting particular users whose safety depends on… you know users in Iraq or in Syria, in Egypt, where their security of their messages actually affects their safety.

The EFF team also realised that some developers and firms proposing secure messaging tools had, while presenting their tools, ‘bent’ the 1.0 grid to their own advantage – more precisely, they had presented a high conformity to the SMS as a label of legitimacy. Again, R2 emphasises that this was a problem particularly in those cases when users lack the technical background or expertise to build their own hierarchy of the criteria’s relative importance, according to their needs or ‘threat model’ (see Chapter 1).

In 2017, a piece of research on user understanding of the SMS, authored by Ruba Abu-Salma, Joe Bonneau and other researchers with the collaboration of University College London, showed that indeed, users seem to have misunderstood the 1.0 scorecard in several respects. Four out of seven criteria raised issues: ‘participants did not appreciate the difference between point-to-point and e2e encryption and did not comprehend forward secrecy or fingerprint verification’ (Abu-Salma et al. 2017b), while the other three properties (documentation, open-source code and security audits) ‘were considered to be negative security properties, with users believing security requires obscurity’. Thus, the assessment concluded, ‘there is a gap not only between users’ understanding of secure communication tools and the technical reality, but also a gap between real users and how the security research community imagines them’ (ibid.).

‘Not everyone needs a bunker’! From a tool- to a context-centred approach

The additional expertise needed by the user to understand the difference between various criteria and their importance emerged as a crucial flaw of the first version of the grid. One of the keys for a ‘new and improved’ SMS, thus seemed to be the fact of taking user knowledge seriously, as a cornerstone of the categorisation: for it to be meaningful, users needed to identify and analyse their respective threat model, i.e. identify, enumerate and prioritise potential threats in their digital environment. R3 remarked that this is one of the core objectives of EFF in several of its projects beyond the revision of the SMS, and noted that there are no direct tools to indicate what threat model one has, but users need to uncover the right indicators in their specific contexts of action:

We’re not answering what someone’s threat model is, we just help guide them in their direction of what to read. We can say like journalists might have good secure communication tools that they might wanna protect their data, but we can’t say how much of a threat any journalists are under because different journalists have different threats.

Furthermore, R2 pointed out that the same wording used to identify a particular threat might have very different meanings or implications depending on the profile of the user who utters it and on the geopolitical context she operates in: ‘there’s still a difference between “I am worried of a state-level actor in Syria” versus “I am worried of a state-level actor in Iran” versus China versus US’. In this regard, the more ‘qualitative’, descriptive nature of the new SMS should be useful to trigger the right reflexes.

In the absence of a universally appropriate application, the new SMS should take the diversity of the users – and the corresponding diversity of their threat models – as a starting point. R2 again resorted to specific case-examples to illustrate this point, citing Ukrainian war correspondents and ‘hipster San-Francisco wealthy middle-class people’ as opposites in terms of needing to worry about the relationship between their safety and the security of their messages. Helping individuals to trace their profile as Internet users, and the different components of their online communication practices, would be a first step towards identifying the threat model that best corresponds to them:

Not everyone has to put on a tin foil hat and create an emergency bunker. Lots of people do, but not everybody. I think that would be great to have an [ideally secure] app but since it’s not there I think it’s useful to tailor things, tailor the threat model.

If for the user the choice of a strong secure messaging tool is in this vision strictly linked to the understanding of his or her threat model, for its part the EFF acknowledges that just as there is no universally appropriate application, the same applies to the definition of what constitutes ‘good’ encryption – ‘good’ security and privacy. Beyond the strength of specific technical components, the quality of being ‘secure’ and ‘private’ extends to the appreciation of the geographical and political situation, of the user’s knowledge and expertise… of whether privacy and security are or not a matter of physical and emotional integrity, which can only be contextually defined and linked to a particular threat model. A high-quality secure messaging tool may not necessarily always be the one that provides the greatest privacy, but the one that empowers users to achieve precisely the level of privacy they need.

Comparing with other categorisation systems

The efforts to revise the SMS could not, for the EFF team, do without a comparison with other categorisation systems. On one hand, the new version of the SMS would interact with the Surveillance Self-Defense Guide, developed by the EFF itself and destined for the purpose of ‘ defending yourself and your friends from surveillance by using secure technology and developing careful practices’.16 Indeed, the contextual approach to users’ needs and threat models appears to be dominant in this project: in stark contrast to the technical properties-based criteria of the first SMS, on the guide’s home page, a number of ‘buttons’ introduce the reader to different paths of privacy and security protection depending on… user profiles and ‘ideal-types’ (Figure 5.3). The revised SMS should have partaken in this shift.

According to R3, this approach based on facilitation, induction and personalisation is informing more broadly the recent EFF efforts, and goes back to identifying the right level of relative security for the right context:

Fig. 5.3 Sample of ‘user paths’ on the SSD home page as of early 2017. These ‘user profiles’ have as of 2019 been turned into a ‘Security Scenarios’ menu (https://ssd.eff.org/en)

We don’t distinguish threat models; we give tools to help users figure out what are their threat models. […] I still would not say we were putting an answer to the question out there. The key to the guide that we’ve created is that we want people to start with understanding their own personal situation.

The EFF was also looking at categorisation systems in the same field produced by other actors – acknowledging that SMS 1.0 has been, in turn, an inspiration for some of them and that there seems to be a need, generally identified in the field, for tools to provide guidance in the increasingly complex landscape of secure messaging.17 R1 engaged in dialogue with several organisations which had the same kind of categorisation projects ongoing or were considering establishing one. A few of these organisations explicitly acknowledged that they were drawing ideas and concepts from the first version of the SMS, but re-elaborating it, which EFF considered a positive thing. Both R1 and R2 refer in particular to the similar effort by Amnesty International in 2016,18 and while R1 acknowledges that

they were really trying to produce something very simple and consumer-based and I think they did that, their report was much easier to digest for the general public’, R2 mentions how ‘I feel they suffer a lot from the same problem that Scorecard had, which is they […] rely on a single number, they gave this score, like 90.5 points out of a 100 [and] you can’t reduce security down to a single number.

The alternative, user-centred approach arose not only as a result of internal reflections on the first version of SMS, but also in relation to how parallel categorisation attempts were performed by other actors promoting online civil liberties. This includes informational security trainers and their recent pedagogical shift from tools to threat model evaluation, as described in Chapter 1.

Conformity to criteria: Evidence-seeking, evidence-giving

A final set of evolutions was meant to move beyond the building of the categorisation system itself. It aimed to question how EFF would request proof of the different secure messaging tools’ conformity to their guidance, and how this evidence would subsequently be provided by the developers of the tools, as well as the encryption/security community at large. Indeed, one of the early criticisms of the first SMS did not have to do with the format of the grid, but concerned the opacity of the ways in which its ‘binary’ recommendations were evidence-supported.

In SMS 1.0, ‘green lights’ had sometimes been awarded for specific criteria as a result of the private correspondence between R1 and the developers, says R2: ‘He would just email […] sometimes he knew who was the developer but most cases it was just like contact @…’. The subsequent version of the SMS would thus adopt a more transparent approach and encourage display of public evidence from the developers, the lack of which may be a deal-breaker:

This time around we are not going to accept as proof of any criteria any private correspondence. If an app wants to get credit for something, it has to publicly post it somewhere. I mean, we may be contacting developers to encourage them to publicly post it. […but] we don’t want to have to say, ‘well, we talked to them’. We want to say they are publicly committed to it. (R2)

In particular, one of the criteria that had raised more objections in terms the evidence provided was the review of the code – a developer, contributing to the previously-mentioned SMS-focused Hacker News discussion thread, asked: ‘What does “security design properly documented” even mean?’. The EFF did not have sufficient resources to review the code line by line, and for several of the tools the code was not available, which is why the ‘external audit’ criterion was added. The lack of resources to dedicate to this task continued to be a problem, one more reason why, in the second phase, the EFF meant to concentrate on what app developers made public via their official communication channels. In parallel, the criterion calling for an independent audit – which, as we recall, had elicited a lot of internal methodological reflection since the beginning – was no longer meant to have a place in the second version of the SMS, once again because of evidence-seeking requirements and their material and human costs. As R1 pointed out, ‘the cost of really doing a crypto audit of a tool is really high. The audit of 40 tools would have taken an entire year for me. So we just did not have the resources’. Interestingly – and while he agrees that the criterion needs to be dropped as such – R2 points out that several companies do their own audits, and the fact that they keep the results private does not necessarily affect their quality:

There are companies like Apple or Facebook […] it’s almost certain they’re doing an audit with an internal team so they will not release it publicly. It does not necessarily mean that the internal team did not do a good job. […] For that reason we feel like the whole audit category does not do a lot. But we are going to still include if the code is open for an independent review because we think that’s important [for some threat models].

Finally, to support the arguments provided in the new SMS, the EFF team expressed the wish to build on the competencies of the encryption communities of practice – cryptographers, professors, people in industry and digital security trainers – in order to get feedback about whether they possessed enough information about a particular tool, and whether the available information was correct. The EFF team anticipates that the search for feedback will be ongoing, to avoid falling into the same trap that had led commentators to wonder why the making of the first SMS had seemingly been a mostly ‘internal’ matter for EFF19 and also to be able to react promptly to important changes in the tools: ‘We try to make it clear that we’re keeping the door open to feedback after we publish it, for anyone we did not get a chance to talk to before we published it. We can’t get feedback from everybody before it goes live’. As tools evolve, what constitutes ‘good’ security evolves, or may evolve, as well.

Conclusions: Sometimes narratives are the best categories

Using the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s prominent attempts at building a grid or guide to assess secure messaging tools, this chapter has sought to examine the role of categorisation and classification in defining ‘good’ encryption, privacy, security and secure messaging. In doing so, it has analysed how, by challenging, re-examining and re-shaping the categories that are meaningful to define the quality of secure messaging tools, the EFF has sparked a ‘global crypto discussion’20 that currently contributes to shape what constitutes ‘good’ security and privacy in the field of encrypted messaging.

Indeed, on one hand, the EFF’s activities, epitomised by the SMS and its revisions, seem to contribute to the ‘opportunistic turn’ in encryption (IETF 2014) that gained momentum in 2014 after the Snowden revelations, and consists in a progressive move of the crypto community towards making encryption ‘seamless’, with almost no efforts required on the part of users. In terms of design choices, this entails a ‘blackboxing’ of quite a few operations that used to be visible to users and that needed to be actively controlled by them (e.g. key exchange and verification, or the choice of encrypted/unencrypted status etc.). The opportunistic turn calls for ‘encryption by design’, and constructs a new user profile, one who ‘does not have to’ have any specific knowledge about cryptographic concepts and does not have to undertake any additional operations to guarantee a secure communication. That shift may also be explained by the growing popularity of ‘usable crypto’ that undermines experts’ monopoly on encryption and makes easy end-to-end encryption accessible outside of the tech-savvy user groups, where users used to be at the same time designers, developers and cryptographers.

However, while calling upon developers for improved usability – demanding that the technical crypto community make some properties, such as key verification, easy for users and independent from user agency – the EFF also puts users at the core of its attempt to develop a better ‘guiding system’, and in doing so, entrusts them with an important decision-making responsibility. To put it in R2’s words, ‘[The aim] is still to push the developers to improve but we realise that people are using it to make choices, so now the idea is [to do this,] instead of just showing the developers here’s what you have to do’. As it is often the case with categorisation and classification systems, the SMS was re-appropriated by the different actors in the community of practice, beyond the intentions of its creators – and several users in particular have relied on it heavily. Attempts at an evolved SMS intended to take this into account to a greater extent; but within the new paradigm that guided attempts to move beyond the SMS 1.0, there is an understanding that users have to question their threat models, increase their awareness of them, and have to know how to make technological choices according to their particular situation – a tool, from this perspective, is ‘good’ if pertinent to the context of use. This paradigm shift is also experienced and reflected upon by the trainers, organisers of cryptoparties and informational security seminars whom we have interviewed in different countries.

The reader may wonder at this point whether there is an (ongoing) epilogue to this story, given the fieldwork for this particular strand of our research ended in 2017. The answer is both that there is continuity with our conclusions above, and at the same time, things have moved in a slightly surprising direction. In March 2018, Nate Cardozo, Gennie Gebhart and Erica Portnoy of EFF published a piece with a provocative title: ‘Secure Messaging? More Like a Secure Mess’ and an equally provocative first sentence: ‘There is no such thing as a perfect or one-size-fits-all messaging app’ (Cardozo et al. 2018). As we kept on reading the article, we realised that we were in fact looking at the latest, and likely the final, iteration of the SMS – one that in describing the intention to create a ‘series’, reads like a selection of articles, all attempts at schematisations and categorisations gone, including the ‘tiers’ organisation that our interviews had unveiled as the EFF’s intended next step:

For users, a messenger that is reasonable for one person could be dangerous for another. And for developers, there is no single correct way to balance security features, usability, and the countless other variables (…) we realized that the ‘scorecard’ format dangerously oversimplified the complex question of how various messengers stack up from a security perspective. With this in mind, we archived the original scorecard, warned people to not rely on it, and went back to the drawing board. (…) we concluded it wasn’t possible for us to clearly describe the security features of many popular messaging apps, in a consistent and complete way, while considering the varied situations and security concerns of our audience (…) So we have decided to take a step back and share what we have learned from this process: (this series will) dive into all the ways we see this playing out, from the complexity of making and interpreting personal recommendations to the lack of consensus on technical and policy standards.

For users, we hope this series will help in developing an understanding of secure messaging that is deeper than a simple recommendation. This can be more frustrating and takes more time than giving a one-and-done list of tools to use or avoid, but we think it is worth it. For developers, product managers, academics, and other professionals working on secure messaging, we hope this series will clarify EFF’s current thinking on secure messaging and invite further conversation (Cardozo et al. 2018).21

Ultimately, the EFF’s conclusion – after, as Cardozo and his colleagues themselves point out, ‘several years of feedback and a lengthy user study’ – can be understood as the celebration of the ‘relational’ concept of risk we introduced in Chapter 1, and as a consequence, of the impossibility, when it comes to secure messaging, of a classical categorisation system including lists, schemas, regroupings, bullet points, tables, columns and rows. The soundness and ‘goodness’ of privacy and security protection in the field of secure messaging cannot be accounted for in a system intended to provide a set of possible answers for all possible readers – even if categories were expressed as open-ended questions aimed at personalising feedback, instead of red crosses versus green dots. A similar approach has been taken by the Citizen Lab’s Security Planner22 project, an interactive online digital security guide that gives a personalised and detailed ‘action plan’ including recommendations on security measures and tools based on users’ responses to a set of questions.

The epilogue of the EFF’s experimentation first with a scorecard, then with a guide, brings us to the conclusion that our fieldwork on the transition from the first to the second version had already unveiled: if a tool is good when it is pertinent for the user(s) and their social, geographical and political context of use, the best categories cannot possibly be anything else than narratives – narratives that do not prescribe, but inspire reflection on who a person is and what they want to do, who their adversary is, and what they want their communicative act to be. For some things and some times, suggests the EFF, open questions and narratives may be the best categories – and a field such as encrypted messaging today, which ‘is hard to get right – and […] even harder to tell if someone else has gotten it right’ (Cardozo et al. 2018), is very likely to be one of those things and times.

Notes

1 A previous version of this chapter was published as Musiani, F. and K. Ermoshina, ‘What is a Good Secure Messaging Tool? The EFF Secure Messaging Scorecard and the Shaping of Digital (Usable) Security’, Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 12.3 (2017), 51–71 <http://doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.265>. Sections are reproduced and adapted here under a CC-BY 4.0 license. The paper was also presented and discussed at the annual conference of the International Association for Media and Communication Research (IAMCR) in Cartagena de las Indias, Colombia, on 19 July 2017.

3 See e.g. the discussion of the code audit criterion at Peter Eckersley, ‘What makes a good security audit?’, EFF Deeplinks, 8 November 2014, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2014/11/what-makes-good-security-audit, which will be addressed in more detail later in the chapter.

5 https://www.eff.org/node/82654. This webpage, introducing SMS v1, is now preserved ‘for purely historical reasons’ on the EFF website. Citations in this section are from a version of this page that was online at the time of our fieldwork (2016–2017) unless otherwise noted.

6 We will return to them in more detail below.

9 Discussion thread on Hacker News, https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=10526242.

10 Formerly at https://www.eff.org/secure-messaging-scorecard, which was taken offline during 2018.

11 https://www.eff.org/node/82654: ‘you should not use this scorecard to evaluate the security of any of the listed tools’.

12 https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=10526242. Citations in this paragraph are from this thread unless otherwise noted.

14 See also https://www.eff.org/node/82654: ‘the results in the scorecard below should not be read as endorsements of individual tools or guarantees of their security; they are merely indications that the projects are on the right track’

17 This issue had also been brought up in the Hacker News SMS-related thread: ‘Isn’t it a bit strange, that there is no such thing as that scoreboard produced by an international group of universities and industry experts, with a transparent documentation of the review process and plenty of room for discussion of different paradigms? (see https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=10526242).

18 https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2016/10/which-messaging-apps-best-protect-your-privacy.

19 See https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=10526242: ‘Why didn’t they consult any named outside experts? They could have gotten the help if they needed it; instead, they developed this program in secret and launched it all at once’.

20 Ibid.

21 We license this text from the EFF website under a CC-BY license: https://www.eff.org/copyright.