8

Conclusion: The Haunted Pharmakon

Assemblage Marketing and Corporate Disguises

Together, the many elements that pharmaceutical companies shape, adjust and assemble constitute markets. These markets are new creations, but because they draw together medical science and health needs they take on an appearance of necessity. They look like entities that have emerged whole from just below the social surface.

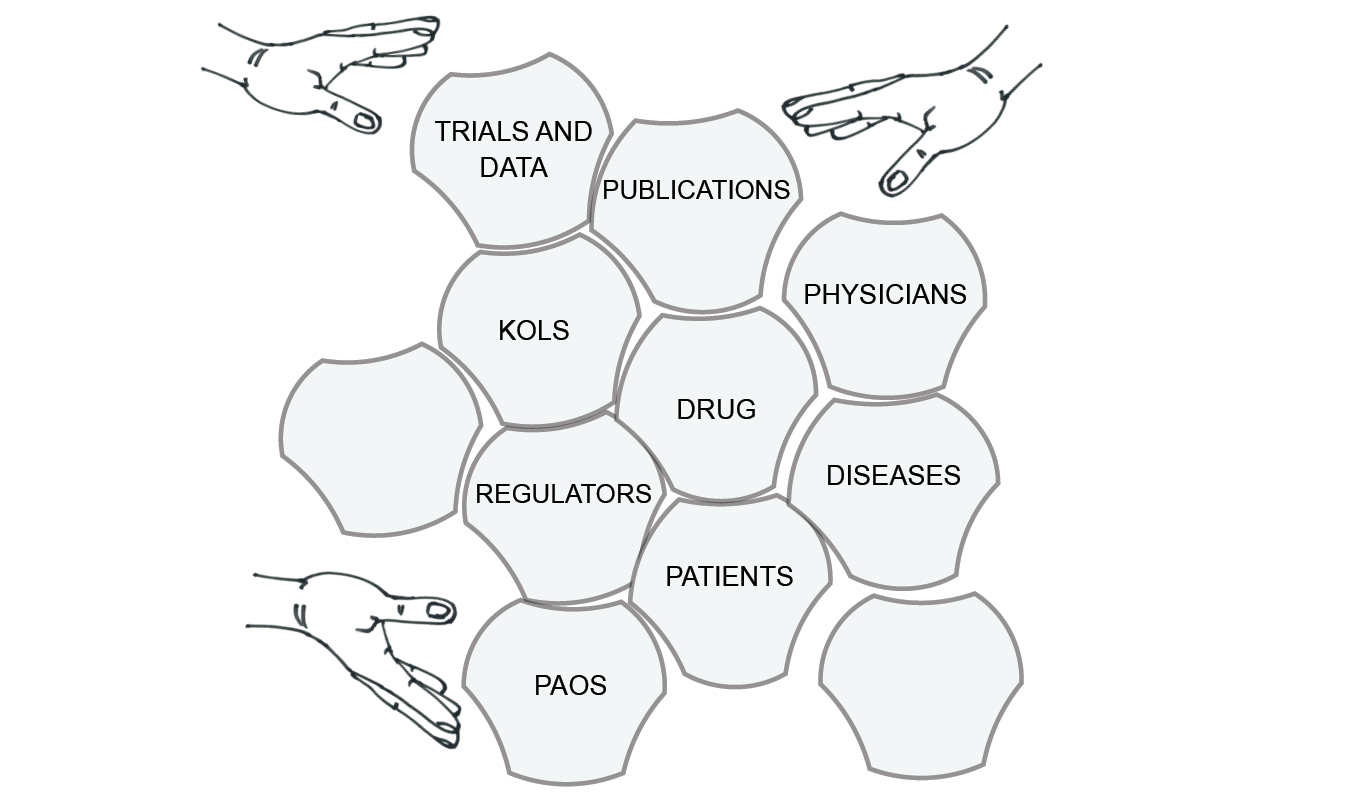

The goal of pharma’s assemblage marketing is to establish conditions that make specific diagnoses, prescriptions and purchases as obvious and frequent as possible. Ideally, all of the elements of a market can be directed towards the same issues, claims and facts, so that the drugs sell themselves. Pharma companies can then recede into the background, and apply only minimal pressure when needed. From the original image of assemblage marketing I presented in Chapter 1, pharma tries to achieve something more like Figure 8.1. Here, the drug is at the centre of the diagram, surrounded by actors, institutions and information that make it successful. In a sense, the assemblage makes not just the market but also the drug.

While a perfectly tight assemblage is only an ideal, sometimes pharma companies get close to that ideal. It should now be clear that these companies systematically influence the production, distribution and consumption of medical knowledge. Pharma companies and their agents make decisions in the running of clinical trials, in interpretations of data and established medical science, in the messages conveyed in articles and presentations, in the timing and location of publications, in the identities of authors and presenters, in what their representatives communicate, and in what their allies say. Companies sustain large and partly invisible networks to do all of this, creating and participating in shadowy knowledge economies.

Fig. 8.1 The goal of assemblage marketing

In the ghost management of research, publication and dissemination, pharma companies see value in letting apparently independent academics and physicians serve as their conduits for scientific information. These key opinion leaders (KOLs) can be thought of as disguises for corporate faces, allowing companies to market their products through more neutral representations of medical science.

Sometimes, the disguise is nearly perfect. Many ghost-managed publications, talks and continuing medical education courses are presented as more or less independent research. Sometimes, not only is the sponsoring company unseen, but so is the product. When it comes to marketing to physicians and researchers, pharma companies can, if they choose, make themselves almost invisible.

Even when they are more visible, pharma’s agents can use elements of disguise. Physicians can take advantage of something like plausible deniability when company influence is cloaked in science – in speaker bureau presentations, for example. KOLs can act with clearer consciences if the substantial benefits they receive are seen as parts of scientific exchanges. The same may be true for physicians benefitting from continuing medical education courses or the attention of company representatives. But whether the ghost-managed medical science disguises pharma interests so that they cannot be seen, or simply so that they need not be seen, the result is often that they are not seen.

The ghostly work of pharma companies to produce, distribute and encourage the consumption of medical information is not merely a corporate use of the patina of science. In the ghost management of medical science by pharmaceutical companies, we have a new mode of science. This is corporate science, done by many unseen workers, performed for marketing purposes, skilfully communicated and disseminated, and drawing its authority from traditional academic science. However, this commercially driven science differs from academic science in the narrow interests behind it and the kinds of choices those narrow interests produce. Unlike most independent researchers, pharmaceutical companies have clear and strong interests in particular kinds of research, questions and outcomes. They want to build markets and increase sales.

The ancient Greek word ‘pharmakon’, I mentioned earlier, can be translated as either ‘cure’ or ‘poison’. According to the ‘inverse benefit law’, the effort to enlarge the market for a drug is correlated with a decrease in the ratio of benefits to risks.1 Increasing the number of people taking a drug decreases its average benefit, and may increase its average risk – adverse reactions to prescription drugs are currently the third or fourth leading cause of death in many countries.2 The pharmakon becomes less cure and more poison.

If almost every decision in the research and publication process pushes the research even subtly in a consistent direction, then that is the direction in which the research will go. We can reasonably expect – and there is abundant evidence to support this – that the industry makes its choices to support its commercial interests. We know that pharma companies’ research produces results that favour its products. We might care just as much about the more nebulous issues of how the kinds of research and questions that pharma supports shape medicine to favour its products.

Because assemblage marketing is a much larger activity than mere advertising, it changes the world in profound but subtle ways. In particular, pharma’s assemblage marketing increases the burden of disease. To increase their markets, pharma-sponsored medical studies and guidelines tend to expand the definitions and prominence of specific diseases. This increases the number of people potentially affected. Pharma’s selective but aggressive distribution of medical information promotes symptoms and diagnoses to physicians and patients. Patients present themselves to their doctors with complaints shaped by pharma promotion and readily available pharma-sponsored information. Physicians may then understand their patients, and patients may understand themselves, in terms laid out by the industry. Big pharma’s invisible hands are making us more sick.

Ghost-managed Integrity

Medicine’s close relationships with the pharmaceutical industry pose moral challenges. At the core of justifications of the connections between medicine and the pharmaceutical industry is the assumption that medicine has the integrity and rigour needed to keep control while welcoming pharma’s invisible hands into its journals, conferences, clinics and more. Medicine and its regulators hope to use what pharma has to offer to improve medical science, education and care. They very rarely see the possibility of interested knowledge, the possibility that the careful deployment of science can support commercial over patient interests: science is taken as a guarantee that medicine can remain pure. This is even though the terms in which medicine evaluates science – and the resulting education and care – are influenced by pharma.

For example, we saw in Chapter 5 that KOLs, without any need for prompting, respond to conflict in their roles by drawing on a range of justificatory schemes, producing a range of moral microclimates.3 The main sources of the justification they provide for working for pharma involve connected claims that they are contributing to patient health by educating other doctors, and that they stand behind their ghost-managed presentations and articles, believing in the products they promote. Their sense of independence or integrity is crucial. They can vigorously insist that they are not paid shills, paid stooges or paid monkeys, even though they are paid. They can focus on the fact that they believe what they say, that they see it as warranted, regulated and useful. If they can speak with conviction, they don’t consider relevant any of the relationships that they might have with the sponsoring company. KOLs can cheerfully take the money, status and perks that pharmaceutical companies offer, believing that they are acting in the interests of health.

Similar things could be said about many of the other actors we’ve met. Doctors who see sales representatives are often confident of their ability to maintain their independence and their scientific standards, and to take advantage of what the reps have to offer, thus helping their patients.4 While some patient advocacy organizations are simple pharma creations, other PAOs are or develop out of grassroots patient efforts, and join forces with pharma in order to conscientiously represent patient interests. Some of the interest in patient adherence is purely to increase sales, but some researchers approach the adherence issue from the position that doctors’ prescriptions improve patients’ health, and therefore that non-adherence is a health problem to be addressed. Even within pharma, publication planners, medical science liaisons, sales representatives and others often justify their actions in terms of communicating scientific truths.

But pharma companies go to some lengths to gain control over the actions, habits, beliefs and loyalties of the people with whom they engage. Relationships, and what those relationships are intended to achieve, are carefully managed, and in the process they are co-opted into promotional plans. By definition, pharma’s careful management efforts impinge on medicine’s actual independence, though medicine may not always be aware of it. People working in medicine may be misled by their sense of integrity, since they are not fully independent.

Not only does pharma put considerable effort into managing its relationships with medicine, but it also creates conflicts of interest. Publication planners, for example, are paid to create sound scientific articles reporting on clinical trials and other studies, and at the same time to help promote products by placing favourable articles in medical journals. It would be surprising if study results weren’t sometimes bent to serve promotional goals. Meanwhile, the authors on those ghost-managed articles receive something for almost nothing: credit for scientific work in trade for their credibility. It would be surprising if they weren’t inclined to accept pharma manuscripts more or less as they receive them, even if the results reported in those manuscripts are spun to serve companies’ interests. KOLs’ conflicts of interest, stemming from their payments for speaking engagements, not only make it more likely that they will give sales messages in their talks, but also make it more likely that they won’t even recognize that this is what they are doing. Conflict of interest has powerful effects, in medicine as elsewhere.5

In addition, integrity does not address central issues in the political economy of medical knowledge. The industry provides roughly half of the funding for clinical trials, and sponsors a majority of the new trials initiated each year. As we’ve seen, pharmaceutical companies produce a significant portion of the scientific literature on in-patent prescription drugs. They and their agents shape these articles, and choose both their authors and the journals to which they are submitted. Companies’ interests influence a myriad of legitimate choices in the design, implementation, analysis, description and publication of clinical trials. The result is still recognizably medical science, but it is science serving very particular and clear commercial goals. The influence goes on: when pharmaceutical companies get physicians and researchers to circulate information, it is the companies’ preferred KOLs doing the circulation and the companies’ preferred information being circulated. If seen as education, the form of continuing medical education in which KOLs participate is one thoroughly shaped by the interests of the companies that sponsor it; this is science chosen to help sell a product. Even if companies are not completely coherent actors, they are coherent enough in their goals that choices at all the different stages of research and communication can point in the same direction.

As a result, when physicians learn about conditions and treatments, they are often learning results created by agents of pharmaceutical companies and transmitted by other agents of those companies. In the end, it matters little what all the participants think they are doing, how honest they are, or how much they believe what they say. They are, inevitably and inescapably, part of large-scale, commercially driven efforts to shape the medical knowledge that physicians have and apply in practice. Where pharma is involved, research, education and marketing are everywhere fused by invisible hands.

Loosening the Grip

Pharma has achieved a considerable degree of hegemony over medical science and the practice of medicine. The industry has succeeded by applying its enormous resources where they can influence taken-for-granted medical knowledge, ordinary medical practice, policies and regulations, and attitudes toward the industry itself and its contributions to health. It is difficult to muster effective responses to the industry’s actions, precisely because it commands so many resources. Attempts to reform pharma-haunted medicine are often met with very effective opposition.

In addition, pharma has so tightly insinuated itself into medicine that pharma appears essential to the functioning of medicine. How would new drugs be developed without the industry? How could medical research run without pharma funding? How would physicians stay up to date without presentations paid for by pharma companies? How would clinics run without the free lunches provided by sales reps? As a result of this infiltration, attempts at reform are often met with genuine opposition from within medicine. There is no point in giving moralizing sermons to physicians and researchers. Not only are sermons ineffective, but the industry is already easily able to counter them, pointing to how much it contributes to medicine and medical research.

Effective ways of addressing the haunted world of pharma should focus on correcting large imbalances in the current political economy of medical knowledge. Unfortunately, this way of understanding the problem doesn’t lend itself to easy solutions. If pharmaceutical companies’ substantial resources give them too much power to shape medical knowledge, solutions have to focus on reducing their resources or substantially redressing the balance of resources.

Given the scale and reach of the pharma industry’s actions, no single solution will address all of the problems it creates, short of closing the industry down. So many reforms have been proposed, and even implemented, that I cannot discuss them here. Instead, I’ll chart out approaches in very general terms.

Responses that challenge pharma tend to assume one of seven forms, not always cleanly distinct from each other: individual withdrawal, safeguarding the quality of information, increasing transparency, restricting pharma practices, applying monetary penalties for illegal actions and harms, promoting the independence of medicine and industry, and disrupting the industry as a whole. I discuss each of these in turn.

Individual Withdrawal

Perhaps the most straightforward, though modest, approach is for individual patients to cautiously and sensibly avoid taking more prescription drugs than necessary, and for physicians to avoid prescribing more drugs than necessary.

One of the starting points of this book is that information does not move on its own, but always requires a mover. I’ve argued that when it comes to medical information, pharmaceutical companies are some of the most important movers, though their efforts are often obscured. Most of us could be much more aware than we are that the health and drug information we receive – even the information that we appear to receive randomly – may have been shaped and transmitted by pharma. At the least, it is always worth asking whether and how much influence pharma has had.

Patients even need to ask this of the information they receive from their own doctors. With that in mind, we might try to avoid becoming patients in the first place by avoiding unnecessary tests, paying more attention to our bodies, using common sense and staying healthy in uncontroversial ways. (This is not an advertisement for ‘alternative’ treatments, which can be both controversial and also embedded in their own problematic political economies of knowledge.)

When we do become patients, we should press our doctors about whether there are alternatives to drug treatment, whether there are older, off-patent drugs – not only are they less expensive, but their effects and side-effects are better known and the interests in propping up a body of knowledge behind them are much smaller. We might also press our doctors to avoid long-term treatments, thinking of us as intrinsically healthy rather than intrinsically diseased. And finally, we should press them about exactly how they gained their knowledge.

For each of these points, there are analogous ones for physicians, who can actively work toward minimalist prescribing and generous de-prescribing.

Safeguarding the Quality of Medical Information

Many people take this issue to be one of ensuring that medical information is sound. Many regulators prevent pharma companies from off-label marketing – for example through their sales reps’ and speaker bureau presentations – so the label reflects evidence that has gone through proper channels.

However, much of the information that pharma promotes is already ordinary. We shouldn’t assume that well-educated and apparently honest physicians and researchers are routinely peddling falsehoods. Indeed, the kind of knowledge they share fits medical standards well, and passes many routine regulatory and scientific tests. It looks like mainstream medical science. This is why medical journals solicit pharma’s articles and apply similar standards to them as they do to more independently produced articles.

Relatively few pharma medical journal articles have been shown to involve scientific fraud involving data or statistics (although of course there is widespread fraud in terms of authorship). For the cases of fraud, correctives to the medical literature can be very useful – seen in, for example, the recent initiative to ‘restore invisible and abandoned trials’.6 But without widespread dissemination, correctives can languish. Meanwhile, pharma companies are distributing their preferred parts of the medical science literature.

The fact that pharmaceutical companies go to such length to disguise their interests suggests that people are prepared to accept that even rigorous science can be affected by interests. At this point in the book, it might seem obvious that science can be shaped by interests, but that idea runs against the common view that pharma can be a valuable contributor to medicine as long as it respects common rules.

Medical journals could stop publishing pharma-sponsored research altogether. The twenty or so most important medical journals have such a lock on prestige that together they could step away from the pharmaceutical industry and show off their clean hands. A set of ‘pharma-free journals’ might even gain prestige.

Given this book’s argument that pharma controls a shadowy economy of medical knowledge, we need to focus on independent quality information. Though they may not always do it, pharma’s invisible hands are fully capable of producing what passes for good medical science, but it is interested medical science.

Transparency

Transparency, captured by the saying that ‘sunlight is the best disinfectant’, is a popular response to the shadowy aspects of pharma’s actions.7 Transparency is especially valuable to those studying pharma. This book has benefitted considerably from access to data – on clinical trials, on payments to physicians – made available through various public disclosures. This, however, is a very roundabout route for sunlight to take to become a disinfectant. Analyses based on disclosures come slowly, and people need to act on them.

Sometimes transparency affects behaviour more directly. The US Physician Payments Sunshine Act, which records all payments to physicians by pharmaceutical companies, had very minor effects on total payments.8 However, it appears that the amount spent on speakers’ fees dropped slightly in the first few years of the programme. And at conferences on managing speaker bureau programmes, I heard anecdotal evidence that the amount spent on speakers’ fees plummeted immediately before the Act was implemented. This suggests that exposing payments was potentially embarrassing to at least some KOLs, or that the industry saw some payments as posing public relations problems.

There is some evidence that exposing conflicts of interest intensifies their effects – people declaring conflicts seem to feel licensed to act less in the public interest, but they are perceived as acting more in the public interest.9 Even setting aside this concern, pharma funding of medical education and research is common; as a result, many people within the medical community evaluate information with industry origins or connections in the same ways they evaluate more independent information, and sometimes even value it more highly. For example, physicians know that sales reps have interests in promoting products, but many nevertheless welcome interactions with those reps.

Finally, transparency can be challenging to implement. Some shadowy practices can remain in the shadows. The industry can subvert efforts at transparency by making data take forms that ensure their uselessness.10 It can also comply selectively, if the risk and consequences of being caught are low enough. For example, it appears that the industry does not fully comply with mandates for transparency around clinical trials, and doesn’t even provide all trial data to regulators, despite legal requirements to do so.11

Restrictions on Pharma

Some strategies for reform simply focus on taking away some of the pharmaceutical industry’s effective tools. In some places, pharma companies are prevented from (or have voluntarily stopped as a result of pressure) providing branded trinkets – Viagra pens, Abilify clipboards and the like. These apparently trivial gifts are effective, but can’t be justified as contributing to medical care or education. In other jurisdictions, regulatory bodies have banned gifts above a certain value – golf trips, tickets to sporting events – that don’t directly contribute to education. In most places, direct-to-consumer advertising is restricted.

All of these measures simply restrict effective sales techniques. However, they are almost always implemented in such a way that equally or more effective sales techniques bound up with education and medical care continue to be allowed. So, golf trips might be banned, but not free dinners accompanied by educational presentations. Branded prescription pads might be unacceptable, but not free samples of the drugs themselves. Direct-to-consumer advertising is restricted, except when it comes to disease awareness programmes. Building on the argument of this book, restrictions on pharma’s effective marketing tools would have to extend to tools that also claim to contribute to medical research, education and care.

Monetary Penalties and Threats

Perhaps the most promising avenue for addressing pharma is through legal action. Leading the way, the Office of the Inspector General of the US has argued that, through illegal marketing, individual pharmaceutical companies have defrauded federal health care programmes. These suits have resulted in settlements, because none of the companies can afford to lose cases and then see their products become ineligible for purchase by Medicare, Medicaid, and other programmes. The settlements have put in place very wide-ranging procedures – called corporate integrity agreements – that temporarily limit some unethical and inappropriate actions. Among other things, these corporate integrity agreements often demand that companies establish firewalls between their commercial and their medical affairs departments.12

Therefore, though corporate integrity agreements may originate in complaints about illegal activity, they are sometimes able to effect safeguards that go beyond simply penalizing one-off instances of such activity. Nevertheless, they are only temporary agreements, and tend to cleave to the logics that accept the value of pharma companies contributing directly to medical research, education and care.

Separating Medicine and Industry

We can see some of the problems around pharma in terms of conflicts of interest, which appear to be handled particularly poorly.13 In an earlier chapter I mentioned the revolving doors between regulators and the industry. The routine application of familiar conflict of interest rules should rule out such obvious problems. But they might also be applied to many other situations, including almost all payments and perks going to physicians. These payments put physicians in positions of conflicted interest with respect to their duties to their patients. Whether physicians recognize it or not, payments are inducements to prescribe. It is a testament to pharma’s success at insinuating itself into medicine that it would be considered almost unthinkable to end all such payments.

One could respond to this book’s account of KOLs with a limited proposal based on conflicts of interest and a separation of powers. There is no obvious public good served by physicians giving promotional talks. Even if there is educational value in promotional talks – a point debated even by the KOLs who give those talks – that value could be provided just as well by sales representatives as by physicians. It would make sense, then, to ban promotional talks by physicians. If promotional talks persisted, they would be given by sales representatives, whose promotional role is at least overt.14

A number of organizations provide independent sources of information about pharmaceuticals, often carefully reviewing the medical literature with highly critical eyes and a commitment to digging deep into the data. These are extremely useful ventures for those physicians and others who consult them. However, they run up against the same problem as corrective publications, namely, that pharma has much better resources for distributing its preferred medical information than have independent agencies.

Recognizing that the integration of pharmaceutical R&D and marketing doesn’t serve the interests of the public, governments could force companies to split these functions – just as electricity generation and distribution are separated in many privatized markets, and, more informally, the editorial and advertising departments of newspapers are supposed to be separated. R&D firms would sell, in a well-regulated manner, their successful products to marketing firms, and so would have less incentive to carry out thorough assemblage marketing.15

Or, at the highest level, governments could separate drug research and marketing more firmly.16 We can’t assume that drug companies will end the integration of research and marketing on their own. A number of commentators have suggested that governments take clinical trials – at least those done for regulatory purposes – out of the hands of drug companies and fund necessary ones through taxes on those companies.17 Such solutions would take an enormous political will that is currently nowhere in view, but might solve many problems.

Disrupting Pharma as a Whole

Other approaches are even more radical. They identify the problems with the pharmaceutical industry as rooted in a core conflict between capitalism and medicine. Seen in this way, real solutions must involve dramatic changes to how drugs are developed, produced and sold. A common proposal is to end patents on drugs, which would allow for broad competition on price and would reduce pharma’s interest in creating markets for expensive treatments. Another proposal is to integrate pharmaceutical research, development and manufacturing into national health systems; this would, presumably, more closely link pharmaceuticals to pre-existing health needs in a context in which costs are contained.18 Perhaps, while researchers and governments work out how to completely reform the system, there could be a moratorium on new drug approvals – ten years would give some breathing space.

Obviously, if governments are mostly unwilling to separate drug research and marketing, they will be much less willing to consider radical disruptions of pharma more generally. At the highest level, governments are themselves highly conflicted, typically seeing the pharmaceutical sector as an important part of the new high-tech economies that they wish to establish.

Stepping Back

Reform should attempt to limit the sheer amount of influence that pharmaceutical companies have on medical opinion. A small number of companies with well-defined and narrow interests have inordinate influence over how medical knowledge is produced, circulated and consumed. The issue here, as in other cases of hegemony, is one of a few actors having accumulated the power to shape landscapes – in this case, some very important landscapes – on which many others base their decisions. And pharmaceutical companies not only shape taken-for-granted medical knowledge and opinions, but in many locations have also naturalized their presence and activities. Most physicians see the companies as playing legitimate roles in their offices, in creating and distributing medical research and in funding and providing medical education.

The high commercial stakes mean that all of the parties connected with pharma’s presence in medicine can find reasons to participate, support and steadily normalize it. It seems that it is here to stay for a while.