2

Microclimates of

(in)security in Santiago: Sensors, sensing and sensations

Martin Tironi and Matías Valderrama

Abstract

Over the past ten years, a climate of fear and insecurity has developed in Chile. Despite the low homicide and crime victimization rates, Chileans generally feel unsafe. This feeling is widespread in Las Condes, one of the country’s wealthiest municipalities. Inspired by the techno-imaginary of Smart Cities, the local government has introduced a series of ‘innovative’ and ‘dynamic’ surveillance technologies as part of its effort to manage and secure urban spaces and wage the ‘war on crime’. These measures include the deployment of aerostatic surveillance balloons more recently, highly sophisticated drones that deliver ‘personalized warnings’ in parks and streets. These drones and balloons offer the municipality a new vertical perspective and allow it to have a presence in the air so that it can give the residents a feeling of security. However, residents and local organizations have protested the use of these technologies, citing profound over-surveillance and raising important questions about the use of these security devices. In this chapter, we argue that vertical surveillance capacities must be analysed not only in terms of the surveillance and control that they generate, but also the affective atmospheres that they deploy in the urban space and the ways in which these atmospheres are activated or resisted by residents. We reflect on how these technologies open up an affective mode of governance by air in an effort to establish atmospheres or micro-climates in which one experiences (un)expected sensations such as safer, disgusted or indifferent.

Keywords: Drones, video surveillance, security, affective atmosphere, Santiago.

Introduction: The occupation of the urban sky

The skies over modern cities are increasingly occupied by new flying devices of monitoring and datafication. Cities are investing significant amounts of resources in order to test this type of ‘smart solutions’ based on mass data recording under the promise of greater levels of efficiency and public safety. This form of intervening in and surveilling the city ‘from above’, using devices such as drones, helicopters, satellites or aerostatic balloons, has given rise to a series of studies that seek to understand their impacts on urban life (Adey 2010; Klauser 2013; Arteaga Botello 2016). Stephen Graham (2012, 2016), has argued that this expansion of the practices of tracking, identifying and setting targets of suspicion in spaces of daily life speak to the increasing militarization of urban management and security. Within this process one can situate the intensification of what has been called ‘politics of verticality’ in which control is not limited to two dimensions, instead governments try to cover a three-dimensional volume of urban space. The air emerges as an ambience that must be controlled and securitized by the use of a series of aerial sensors and technologies that generate a vertical distancing between control rooms and the experiences of entities that coexist with/under the aerial gaze of such technologies (Adey 2010; Graham and Hewitt 2013; Klauser 2010; Weizman 2002).

In dialogue with this discussion of the urban effects of this new form of surveilling urban life from the sky, this chapter analyses the case of Santiago and its recent incorporation of aerostatic balloons and drones to surveil the municipality of Las Condes, one of Chile’s wealthiest areas. Described as pilot projects and experimental initiatives, these surveillance devices were introduced within a frame of a ‘war on crime’ mobilized by the right wing, attempting to improve the climate of insecurity and fear that every inhabitants supposedly perceive on a daily basis. In spite of criticism and opposition from citizen groups, these technologies are viewed as a great ‘success’ by those responsible for their introduction1 and have begun to be evaluated by other cities in Chile.

Based on an ethnographic study of the process of implementation and operation of aerostatic balloons and drones in Las Condes, we argue that these technologies’ vertical capacities should not only be analysed in terms of the surveillance and control that they generate, as tends to be the case in the literature, but also in terms of the atmospheres (Anderson 2009; Adey et al. 2013; McCormack 2008, 2014) that they deploy in the urban space. Adopting an approach from Science and Technology Studies and perspectives informed by the affective turn, we analyse these surveillance technologies as atmospheric interventions in the city. We seek to move beyond the idea of the fixed ‘impacts’ of security technologies on the city to examine how the presence of these flying video surveillance devices in the urban sky participates in the deployment of what we will call atmospheres or microclimates of (in)security.

This analysis is particularly relevant in the Latin American context, where there is a growing militarization of the modes of securing urban spaces, particularly through the use of transnational aerial surveillance devices (Arteaga Botello 2016). It is necessary to problematize the belief that technological solutions are imported from the North to Latin America as stable black boxes with preset qualities and functions. We demonstrate the importance of studying how these aerial surveillance devices are re-created and re-signified in local contexts, considering the entanglements, knowledges and situated frictions that are produced. We seek to contribute to the discussion of sensing security in the urban space in the Global South, showing that spaces and individuals are not only ‘surveilled’ through monitoring practices and data infrastructures, but also with sensors and devices that activate different levels of affectations that tacitly condition emotions and atmospheres of (in)security.

Specifically, the chapter describes two displacements. The first is related to how the drones and balloons form part of an experimental political strategy to make residents’ atmospheres and sensations more manageable with regard to security. The individuals responsible for the technology argue that the war on crime is not won solely by improving statistics, it requires intervention oriented towards influencing people’s sensations and sensibilities. Second, in regard to the effort to produce sensations of security among residents, we analyse the multiple feelings and situated forms of knowledge (Haraway 1988) that the surveilled individuals experiment in the everyday coexistence with the flying devices. These registers reveal how the attempt to make and sense the city secure are exceeded by contingent and indeterminate modes of inhabiting and weaving together atmospheres, in which experiences, materialities, representations and affects mingle. In other words, the work to condition atmospheres of security among the population are far from being lineally and uniformly deployed, and are instead the result of specific entanglements and micro-resistances distributed in diverse agencies and contexts.

Atmospheres and the city

A cluster of publications mainly based on cultural geography and non-representational theory have emerged in the past several years that are interested in understanding territory and technologies beyond their physical or discursive qualities, emphasizing the need to incorporate the sensorial and affective dimensions that they involve (Thrift 2004; Anderson 2009; Bisell 2010). The consideration of affects in the construction of spatiality, environments and urban practices pays attention to how emotions and affectivities shape perspectives, forms of behaving and doing, deploying peculiar modes of production and appropriation of space. While this approach has been particularly important for examining infrastructures and practices of urban mobility (Bisell 2010; Merriman 2016; Simpson 2017; Tironi and Palacios 2016), it also has begun to be used in surveillance studies to explore how technologies oriented towards the control of spaces and populations install particular atmospheres in the space (Adey et al. 2013; Adey 2014; Ellis et al. 2013; Klauser 2010).

A relevant concept for this work is ‘affective atmospheres’ (Anderson 2009; Ash and Anderson 2015; Bissell 2010; McCormack 2008, 2014; Stewart 2011). Understood as heterogeneous and ambiguous configurations in which the presences and absences, the visible and invisible are connected, this concept reveals that the issue of affects goes far beyond a purely subjective matter and is rooted in material and social circumstances, bodies and imaginaries, creating realities that influence how people feel and act (Bissell 2010). The qualities of affective atmospheres cannot be reduced to words or numbers because they circulate and are felt through various senses, involving sight, smell, taste, sound and any other form that affects bodies, both human and non-human. Affective atmospheres manifest themselves performatively before they are manifested through discourse. Prior to a conscious discourse, the concept of affective atmospheres presents as circulatory, pre-narrative: ‘they are neither fully subjective nor fully objective but circulate in an interstitial place in and between the two’ (Adey et al. 2013: 301).

Exploring the idea of atmosphere, McCormack (2008) suggests that this concept is commonly defined in two ways: in a meteorological sense as the gaseous layer that surrounds a celestial body like the Earth and in which entities that inhabit said planet breathe and live, and in an affective sense as an affective situation or environment that surrounds or envelops a group of entities under a general or shared feeling or state, such as when one define a festive atmosphere during celebrations. An important element for our argument is related to the vague and diffuse nature of atmospheres: their qualities are not given and cannot be causally attributed, but are instead registered in and through sensing bodies (McCormack 2008: 413). They have the capacity to condition subjectivities and situations in a distributed and absorbing manner that is at once invisible and indeterminate (Böhme 1993; Bissell 2010). This idea is shared by Anderson (2009) considering that affective atmospheres are ambiguous because they are not only generated by the things or subjects that perceive them but are always present in the diffuse intersection or entangling of both.

This ontologically dynamic status of atmospheres requires that attention be paid to the conditions that give life to them, overcoming a vision in which the atmosphere is conceived of something ‘out there’. On the contrary, it is important to explore the materiality of atmospheres, how they are sensed and experienced, and how this atmospheric sensibility affects our participation in the world. In this sense, Ingold (2012) suggests that atmospheres should be understood as a becoming-with, that is, rather than representing fixed entities, they arise from the entanglements between multiple entities or forces (humans, chemicals, weather, wind, etc.) in particular places, and are perceived in different ways by different sensing bodies. As such, the urban ceases to be a well-defined container and is woven through environments and situations that constitute the threads of the city. As Anderson put it, ‘atmospheres are perpetually forming and deforming, appearing and disappearing, as bodies enter into relation with one another. They are never finished, static or at rest’ (Anderson 2009: 79).

The conditioning and design of atmospheres

Atmospheres shape how people feel and think about the spaces they breathe and live so it has become of great interest how atmospheres can be ‘designed’, ‘engineered’, ‘sealed off’, ‘intervened’ or ‘intensified’ by different means. Through the composition of various elements, atmospheres can deeply absorb many actors in almost unnoticed ways, but in other cases they could be more notorious. As Edensor and Sumartojo (2015) argue, this may depend on the skills of professional and non-professional designers of atmospheres and how they composite, curate or manipulate different materials through design.

This point has been addressed in depth by Peter Sloterdijk in his spherology and his question about the conditions for the deployment and persistence of life on the planet. In a world where security in the largest circles from traditional theological and cosmological narratives has been lost, for Sloterdijk (2011 2016) modernity have been producing technically it’s immunities by the design of interiors or spheres that protect or contain life: ‘Spheres are air conditioning systems in whose construction and calibration, for those living in real coexistence, it is out of the question not to participate. The symbolic air conditioning of the shared space is the primal production of every society. Indeed – humans create their own climate; not according to free choice, however, but under preexisting, given and handed-down conditions’ (2011: 47–48).

For Sloterdijk, the twentieth century will be remembered for the development of ‘atmotechnics’ innovations or technologies for atmospheric design or climate creation: ‘Air-design is the technological response to the phenomenological insight that human being-in-the-world is always and without exception present as a modification of “being-in-the-air”’ (2009: 93). As Sloterdijk shows, the recognition of our ontological condition of being always enfolded in atmospheres in coexistence with others was directly exploited in the gas warfare, through the use of chemical weapons to make unbreathable the enemy’s air. The terrorist principle of intervening the environment (the atmosphere) instead of the system (the enemy’s body), was generalized to everyday life through the design of interiors like shopping malls, clinics or hotels. The hygienic cleaning of the air is no longer sought, but rather with air design it is intended to intervene directly the atmospheres of these spaces to induce pleasurable sensations in people and facilitate consumption (2009: 94). Similarly, Böhme signals the ‘increasing aestheticization of reality’ (1993), where we find the everyday making of atmospheres through the aesthetic work of multiple objects (like stage sets, advertising, landscapes, cosmetics, gardens, music, art, and so on) with the sentient or observer subject.

Within this growing conditioning of the air, atmospheres are becoming objects of concern for security. Based on Sloterdijk’s spherology, Klauser (2010) proposes that we think about the efforts to develop an urban security agenda as an entanglement of practices, technologies and architectures of policing, surveillance and enclosure that are not only oriented to the ground but also increasingly to the air. From this view, security is becoming an atmosphere formation force, splintering the urban volume in multiple psycho-immunological spheres of protection. With the unfolding of drones and everyday security technologies, Peter Adey (2014) speculates that security becomes more alive, encompassing and immersive, registering and resembling the sensibilities of the sensing bodies in the city. Feelings of greater ‘security’, ‘tranquillity’ or ‘hospitality’ are intended to be engineered and contained atmospherically through the arrangement of surveillance technologies, posters, air condition, music, etc. providing new forms of sensing and controlling (Adey et al. 2013). Therefore, in the discussion of the military nature of vertical technologies for security, there is a need to turn our attention to the intervention of micro-climates through the affective relationships between the sensorial presence of these technologies and the ambiguous and diffused feelings that they may produce in everyday life.

Following this literature on the – always partial and fragile – modes of creating self-sealed atmospheres, we believe that aerial surveillance technologies are used to try to generate ‘a state of being immersed in a psycho-immunological sphere of protection’ (Klauser 2010: 327). Here we do not emphasize on how individuals are disciplined and/or controlled, but instead we demonstrate how the ambiguous aerial intervention activates sensations and forms of sensibility, politically and affectively configuring urban life. Following Rancière (2000), we understand politics as an ontological operation that defines the sensible, that is, what is visible and thinkable, what can be spoken and what is unspeakable or noise. But this ‘partition of the sensible’ (2000: 12) may operate under a regime that Rancière calls police in which an effort is made to distribute functions and capacities, the public and the private, that which can be perceived and named. In this sense, we will show how these aerial surveillance technologies seek to provoke specific affective atmospheres, trying to reconfigure the city’s sensible distribution.

At the same time, we focus on the resistance to those efforts to design and condition atmospheres of security. The situational nature of affective atmospheres, which are constantly being built and becoming-with, requires that we examine the surveillance situations as moments in dispute and negotiation. As Edensor and Sumartojo (2015) suggest, the enfolding of an atmosphere is always conditioned by social, historical, cultural contexts as well as the personal background and trajectories of each body. Thus, rather than considering the entities absorbed or immersed in an atmosphere as passive and uncritically actors with no agency, they actively constitute their own sensory experience. They can resist, modify and charge the atmosphere with unwanted or unforeseeable tones or sensations for their designers. Therefore, is relevant to show how an atmosphere can be felted and experienced in unexpected ways by different sensing bodies.

On an empirical level, this kind of atmospheric intervention is examined using the example of the municipality of Las Condes and its increasingly introduction of sensitive and aerial technologies to fighting crime. Here we propose to understand these surveillance air balloons and drones as a way of affective atmospheres creation or air design in the sense that these security technologies modify the mood and sensibility of inhabitants. Their presence in the sky, sensing and registering urban spheres, affect how bodies feel, interact and lives in the urban space. In this sense, we wanted to explore not just what people feel about these surveillance aerial systems but also ‘how they act as sensors working on the human body and generate affects in human bodies.’ (Lupton 2017: 8).

This chapter is based on two periods of fieldwork. The first was conducted in 2015 and focused on aerostatic balloons, and the other took place in 2017 and was centred on the use of drones. We conducted approximately 20 interviews with key stakeholders such as municipal officers, council members who supported and opposed the use of these technologies, members of social organizations, attorneys, residents and others. In addition, ethnographic work was carried out in the urban sites where these balloons and drones were situated. We went on guided walks and had conversations with residents and visited the mobile operation centres for these technologies. Finally, the study includes a thorough review of secondary documents, including media coverage of the controversies and legal and administrative documents that were generated through the introduction and judicialization of these technologies.

The climate of insecurity and surveillance technologies in Las Condes

Although Chile has historically reported some of the lowest homicide and victimization rates in the region, a feeling of insecurity and fear has intensified over the past few years. This sensation is constantly mentioned in public opinion surveys, which suggest that people believe that crime is rising and public security appears as one of the key concerns of the population (CEP 2017). This climate of insecurity has been particularly present in the municipality of Las Condes, which is one of the wealthiest in the nation. A series of high-impact crimes took place in 2014, including ATM, jewellery store and vehicle robberies and two explosions in metro stations. City council members and residents staged cacerolazos – protests during which participants bang on pots and pans – and called for specific measures to be implemented to win the ‘war on crime’. This feeling calls into question the low crime statistics that had been reported in the municipality at the time. Some believed that crime reporting did not manage to capture the ‘real’ level of criminality in the area and in the country in general due to factors such as under-reporting of crimes. For others, such as Las Condes Mayor Francisco de la Maza, citizens’ fear was driven by high-impact news coverage that generated a sensation that was different from the ‘reality’ of crime in the municipality (Las Condes Municipal Council 2014a: 10).

In response to these events, the Municipality of Las Condes introduced a series of ‘technological solutions’ that would be categorized as innovative and smart in order to ensure complete, flexible surveillance of the urban space and thus reduce criminality in the area. These have included the deployment of a video surveillance system based on aerostatic balloons, algorithm-based camera control systems, facial recognition and license plate detection, citizen security app SOSAFE, panic buttons and anti-carjacking systems, lenses with integrated video cameras for guards and most recently the use of drones that provide ‘personalized warnings’ in public squares.

In this paper, we focus on the transnational travel and adoption of the balloons and drones for video surveillance in the municipality. Rather than cantering the discussion on the effectiveness of these aerial technologies when it comes to detecting and reducing crime or the legal aspect of the violation of privacy, our intention here is to reflect on how these technologies intervene in the urban sensibilities. We argue that these technologies have a capacity beyond that of detecting, recording and discouraging crime, an ‘affective capacity’ to condition atmospheres of security among residents.

Aerostatic balloons

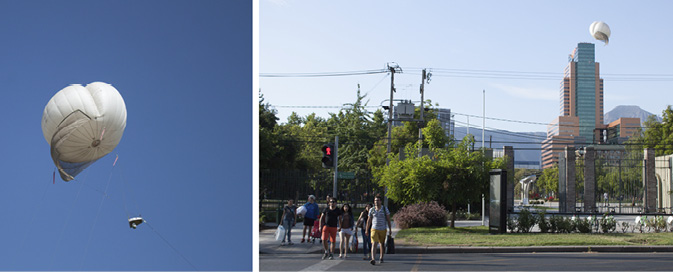

Aerostatic surveillance balloons (for a more complete analysis, see Tironi and Valderrama 2016), were presented in September 2014 as one of the most important smart innovations of the municipality of Las Condes. Former mayor Francisco de la Maza, proposed that these ‘high technology aerial cameras’ be purchased as they were successfully being implemented in the university town of College Station, Texas. He argued that if the municipality had two or three of these cameras ‘nearly the entire municipality of Las Condes could be surveilled’ right down ‘to the size of an ant’ (Las Condes Municipal Council 2014b: 9). In response to this proposal, a service commission travelled to Texas to learn about the scope and characteristics of the surveillance system.

The Skystar 180 tactical aerostatic system was developed by the Israeli firm RT Aerostats, which was founded by a retired colonel who had served in Beirut and Gaza named Rami Shmueli. The device consists of a helium balloon measuring 5.7 meters in diameter that can fly up to 300 meters. A video camera with night vision that can swivel 360° degrees is hung from the device, allowing someone up to 5 kilometers away to be observed. The elements are connected by an electrical cable to a compact trailer, and the set is operated from land by two or three agents in a van or enclosure near the trailer. The corporate brochure describes the device as the perfect tool for surveilling fixed sites such as military bases, temporary military camps, strategic facilities and borders where there are high risks of hostility. While the balloons were initially designed for military use and were deployed on the Gaza Strip and more recently on the US–Mexico border, the company has expanded its scope, selling the military intelligence system to local police departments such as the College Station traffic control unit and to security services for massive events such as Rio de Janeiro’s Carnival or the 2015 Climate Change convention in Paris.

After learning about the technology in College Station, the Las Condes service commission returned to Chile convinced that they should buy it. In order to bring the balloons to the Chilean context, they sought to erase or minimize the military origins of the technology, invoking it as a global, civilized tool that had been adapted for Santiago’s urban context. In interviews and news pieces, the mayor, councillors and municipal directors constantly emphasized the balloons’ capacity to capture evidence of crimes and to have a ‘dissuasive effect’ on criminal behaviour and drug trafficking when criminals recognize that they are under the gaze of the camera. In addition, it was stressed that the balloons would provide more dynamism and flexibility in surveillance and management of the public space, covering a greater visual radius. This would eliminate the need to install many fixed cameras and would decrease oversight costs, identifying broken pipes or traffic lights, crowds of people or traffic problems more quickly. Moreover, the balloons would be described as ideal for the physiognomy of the municipality because of the topography of the hills and considerable variations in altitude, which would eliminate the possibility of using traditional short-distance fixed cameras. It was argued that the terrain necessitated an aerial, vertical vision with greater range for city management.

Also, efforts were made during the negotiations to downplay the military-Israeli roots of the equipment and ‘Chileanize’ it, creating an alliance between RT Aerostats and the Chilean security technologies firm Global Systems, transferring knowledge and technical capacities for the use of the technology. The military intelligence functions of the balloons were removed from the bidding terms, and the equipment was described as a ‘surveillance and traffic control system’, and part of the financing was taken from the municipality’s transit department.

Once the bid was awarded in May 2015, the Municipality of Las Condes established a rental contract with the company Global Systems for two balloons, one mobile and one fixed, and delegated their operation and maintenance to Global Systems. The importation of a foreign technology involved lack of knowledge of the device’s surveillance capacities and possibilities, which meant that trainers had to travel from Israel for two months to prepare the Chilean staff behind the balloons. Two Global Systems staff members were assigned to five or six hour shifts for each balloon. They shared administrative tasks such as recording events, controlling the balloon’s height, monitoring the wind and controlling the camera using a joystick.2

Fig. 2.1 Surveillance balloon in Las Condes

In regard to the experience of the balloon operators, surveillance is never complete or so ‘intelligent’ because there are no analytics or sophisticated algorithms for interpreting the images. As such, the criteria of the operators when controlling the joystick regarding what to look at and focus on become very important. Wind, climate, geographic conditions and the restrictions set by the General Civil Aeronautics Directorate or DGAC regarding maximum heights would also be important conditions for the surveillance system’s capacities. For example, some of the main obstacles to visibility were the force of the wind, tree tops and high buildings, the latter generating blind spots that could not be accessed (field notes from 26 October 2015). According to one municipal director, the cameras had to follow roadways ‘but it is very hard to find something on a roadway because everything is moving and the camera is moving’ (Director, Municipality of Las Condes). In fact, the operators interviewed told us that they had not detected any ongoing crimes, just traffic accidents, couples having sex in public and 3-7s (people behaving suspiciously). The balloon operators believe that the devices do not reduce crime definitively, but just displace it: ‘The fact that the balloon is there and the bad guys see it, persuades. I personally feel like they just go someplace where there are no cameras.’ (Operator 1, Global Systems). The balloons are thus catalogued as ‘just another complement’ to other municipal safety policies, which the employees believe were already quite good.

Drones

The introduction of drones for video surveillance in Las Condes did not emerge as a result of a decision made at the top of the municipality’s administration as was the case with the balloons, but through a proposal made by a municipal worker. A former police officer and municipal inspector from the Las Condes Security Direction was a big fan of drones and had a great deal of experience using them recreationally. Connecting his hobby to his policing of the municipality, he began to draft a proposal for using drones in public safety work. In January 2017, after word got out that the municipality of Providencia was thinking about using a drone system, the proposal began to gain traction in the mayoral administration of Joaquín Lavín. The idea was discussed on two occasions by the Municipal Council. In contrast to the case of surveillance balloons where a large amount of money was spent without an assessment of their efficiency, the council members unanimous support a ‘pilot project’ of drones for surveillance with an initial period of evaluation and testing.

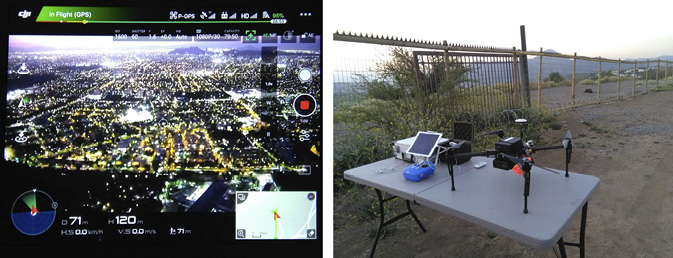

Following a public bidding process, in March 2017 the Las Condes Municipality purchased two DJI MATRICE 600 PRO drones to the DroneStore (Zalaquett y Avendaño Ltda.), the Chilean authorized DJI dealer. Da-Jiang Innovations (DJI) is a Chinese company founded in 2006 and based in Shenzhen, widely considered China’s Silicon Valley. This company has pushed the design of drones for non-military purposes such as film making, agriculture, security, search and rescue, energy infrastructure and recreational uses, becoming the world leader in the civilian drone industry. Specifically, the Matrice model was designed for industrial applications. It weighs around 9 kilos, and has an emergency parachute and a modular design that makes it easy to mount additional modules. It can travel at a maximum speed of 65 km/h and can fly autonomously for up to 32 minutes. he system also have a DJI Zenmuse Z30 camera weighing 549 grams with an optical zoom of at least 30x and digital zoom of at least 6x, which allowed for a broad range of vision.

The municipality decided to train internally the staff required to manage the new technology. The municipal inspector who contributed to the process of adopting the drones agreed to train seven operators (including five municipal inspectors) on the aerial technology. Three of these employees would go on to form part of the Municipal Aerial Surveillance Brigade, which became responsible for drone operation to support Public Security work. The Brigade’s work began in April 2017, initially supporting the ‘Vacation Phone’ plan which consists of ‘taking care of’ residents’ homes when they were on vacation. However, the focus quickly changed because, as the municipality explained, ‘It was very difficult to take care of them or know if something happened, because we were only looking from outside of the gate, so we could only know whether or not someone had broken the gate or opened a window’ (Las Condes Public Security Direction). Furthermore, the regulations regarding drone use in urban space establish that in order to surveil homes, each property owner would have to submit a notarized letter to the municipality authorizing the drones to fly over their house. This limiting factor (there could be 2,000 homes assigned to a single flight) caused the municipality to change their focus to surveillance of public squares, parks and public spaces. As a council member stated, ‘The purpose of the drones ended up being the squares… there was a lot of alcohol and drug use in certain squares’ (Council Member A, Las Condes). The devices became a tool for surveilling and patrolling the 15 plazas regarding which the most complaints for drug trafficking and alcohol abuse focused. The sophisticated cameras that were mounted on the drones allowed them to obtain evidence that could be used in police or prosecutor’s office investigations.

The purpose of the drones’ use was not the only element to undergo changes. Once introduced in Las Condes, the devices acquired new ‘Chilean-style’ functionalities. As one member of the brigade said, a drone is ‘like a tailor-made suit’ to which one can add elements in order to respond to certain requests or needs. First, in response to an announcement made by the mayor on social media, drones were equipped with speakers connected to a radio so that the operator (municipal inspector) could interact with the people who were committing crimes or required assistance. Another drone was subsequently outfitted with special LED lights for night monitoring (field notes from 13 November 2017). For the winter of 2018 a thermal camera was added to one of the drones to monitor and sanction the use of chimneys on days of high environmental pollution. The drones were thus catalogued as ‘Chilean’ and unique, manifesting an intervention in their design and functionalities.

The implementation of the drones was accompanied by a strong municipal communications plan to legitimate the benefits of their use. The mayor himself used Twitter to defend the measure, publishing images and videos, directly addressing questions and criticism posed by residents who were opposed to the technology. The municipality claimed that the drones had increased surveillance and optimized municipal resources, becoming more effective than a guard and more precise, flexible and inexpensive than the surveillance balloons. The media exposure of the drones was such that they were included in a local military parade.

Fig. 2.2 Military parade with drones

Fig. 2.3 Drone assembly and aerial view

The daily use of the drones is as follows: The drones are launched from five closed areas that are agreed to by the municipality and the DGAC. An operations centre is installed in each of those areas, and the drones are assembled there. Operators review the flight requirements such as battery loads, ensure that the trip memory of the drone is restarted and verify that the weather conditions are optimal. Drones are not used if it is raining or windy. They can still fly but use more energy and thus have a shorter autonomous flight time. The flight route varies but cannot exceed 500 meters from the departure area or last more than 32 minutes (battery life). The devices’ actual use depends on the mission that is to be completed for that day. Specific requests submitted by the Investigation Police (PDI) require the drones to be as unobtrusive as possible, identifying the suspect and hiding their lights so that the suspects’ behaviour does not change (field notes from 13 November 2017). By contrast, patrolling of public plazas to discourage people from committing crimes involves making the drone’s presence known. The operators may turn on the lights or interact through the speakers in these cases. One of the drone operators said that ‘often just placing the drone over the plaza makes the people causing trouble leave’ (Revista Drone Chile 2017: 17). This is indicative, again, of the importance of the presence/absence of this kind of technologies in the urban sky, an issue that we will further explore in the next section.

Conditioning atmospheres of security in Las Condes

The analysis of the incorporation of these two technologies in the municipality of Las Condes shows how the purposes of the surveillance systems were reconfigured as they travel to Chile and were inserted into the urban space. Efforts were made to erase the military origins of the drones or balloons by trying to ‘Chileanize’ the technologies and give them new applications. But at a deeper level, and based on the discourses of those responsible for them, their capacities would go further than detecting or discouraging crime. They would also have a less visible or publicly recognized affective capacity. The municipality is aware that both the drones and balloons are not only a technical solution, but also an instrument that intervenes in and reconfigures the dominant ‘climate of insecurity’, which is associated with feelings of fear and anguish on the part of residents. For example, the municipality’s Security Direction representative stated:

Las Condes is the municipality in which crime has fallen the most over the course of this year, but people continue to feel fear. The fear that people feel does not reflect reality. Today people can say, “Yeah, the numbers are down but I am still afraid and I know there is crime because I see it.” And that is a reality. It is a highly subjective matter because it is a feeling, and it is an enormous challenge to address. (Reyes 2017)

It has become necessary to try to manage and shape residents’ feelings. Decreasing fear is not just a matter of operations, but is mainly sensible and environmental. This has led officials to seek out ways of managing people’s feelings, combatting fear, anxiety or panic. It is not only important to manage the issue of crime using functional instruments or declaring decreases in crime rates. It also becomes necessary to manage the sensations and affective climates around people’s security. The solution is not limited to increasing the number of security agents or putting more fixed cameras on corners. It involves creating secure atmospheres and making people feel that they are living in a sphere of constant protection and care.

Along this line, the Las Condes Public Security Direction has implemented various initiatives in public spaces in an effort to increase the sensation of security, such as lighting streets, erasing graffiti and installing home alarms. These measures are all meant to decrease the sensation of ‘disrepair’ or ‘lack of protection’ of certain neighbourhoods. The introduction of aerial video surveillance technologies come to constitute another step in this atmospheric conditioning agenda. The audible and/or visible presence of drones and balloons above Las Condes and the meanings attached to these technologies connected to their smart nature seek to establish an air design or conditioning of certain affective relationships between the residents and their environments, generating the sensation that they are being ‘protected’ or ‘surveilled’ on an ongoing basis. The aerial surveillance technologies are conceived by their proponents as having the ability to trigger perceptions and feelings of security among passers-by. As such, the presence of the drone was considered from the outset as a way of amplifying the presence and power of the municipality in and on the neighbourhoods. ‘Some communities have told us that they want a drone to be sent there. In that sense, the drone can be assimilated by being there, in the sense of making its presence known.’ (Las Condes Safety Direction). Similarly, during our field trips in the communities, some residents (including children) mentioned that the balloons made them feel like they were being observed, which produced a feeling of more security and tranquillity for example when they were walking at night.

These examples show the capacity of these technological devices (balloons and drones) to make some people feel emotions of security. The operations are part of an attempt to decrease crime rates but also to manage affective atmospheres. We see a form of surveillance emerge here that seeks not to internalize the norm through a certain action but to evoke and intervene in the sensations of security of the bodies, assuming that emotionally affected bodies can contribute to generating atmospheres or microclimates of greater security.

Excess, violence and ambiguity

The affective capacities of these technologies in regard to conditioning atmospheres are never unidimensional or confined to a single intention of those who seek to produce sensations of security. We identified feeling of displeasure, vulnerability, indifference and even insecurity in some actors, that goes against the sensations of security that were sought, but these sensations nonetheless coexists in urban space despite the intention of the municipal authorities.

An attorney from Las Condes and other residents filed a remedy of protection against the balloons, arguing that their mere presence symbolically generated the same level of displeasure as seeing military officials with machine guns in the street. The balloons’ omnipotent and omnipresent observation disrupted their social lives, generating a feeling of vulnerability. He insisted on this:

You have a military device that was built for war operated by a mayor, not even a mayor, by private operatives who are recording a large, unspecified number of people, 24 hours a day every day in public and private spaces. It seems the closest thing to a Western world nightmare. (Independent attorney)

Activist organizations also filed remedies of protection against the balloons and drones, denouncing the violation of privacy by these aerial technologies and limitations on freedom of movement. The devices’ vertical nature simulated ‘a combination of the panopticon and the Eye of Sauron’ over the city (Opposition D, Derechos Digitales). According to the NGO Derechos Digitales, residents have changed their way of life because of the balloons’ proximity. One of the victims had a balloon located 90 meters from her home and said:

I can imagine the clarity with which they can see my bedroom and it gives me chills. I have to keep my windows closed and I can’t live the way I used to live because I feel like I am being watched 24 hours a day, seven days a week. (Garay 2015)

These descriptions seek to emphasize the negative effects of the presence and over-surveillance of these technologies, making visible the affective states of vulnerability and precarity that these devices would activate in the municipality through their mere presence in the sky. The efforts to ‘militarize public safety’ are also criticized in an attempt to stop the propagation of these aerial tools in other spaces.

What we could call the “pacification” or “civilization” of military equipment does not have to do with changing its name. It has to do with the disproportionate use of force…. No matter how dangerous a neighbourhood may be, you don’t go in like Rambo with a machine gun firing or tank. You have to react proportionally. This is the same with the balloons. You can paint it, you can civilize it… the problem is not so much its appearance but what it is. (Opposition C, Corporación Fundamental)

A sort of military ontology is manifested that re-emerges despite the municipality’s attempts to whitewash the military tints of the technologies. In addition, residents say that the technologies may inhibit criminals’ actions but they may also affect the behaviours of residents in the public space because they know they are always being watched.

If you know that they may be watching you, you stop doing certain things… if I know that I am in a radius in which a drone might be surveilling me, I will behave in the way in which the drone wants me to behave. (Opposition E, Fundación Datos Protegidos)

These surveillance technologies are again ascribed a capacity for generating an affective atmosphere in their radius of vision – which is indeterminate and dynamic, changing both conducts and sensations by making the presence of these technologies visual or audible. When we asked to activist organizations about how they interpreted the adoption of these devices, some said that they were sensationalist measures ‘showier than effective’ (Opposition F, Derechos Digitales) because they mainly serve ‘to provide the feeling that something is being done about crime’ (Opposition E, Fundación Datos Protegidos). If local authorities managed to decrease crime rates, they would not have an impact for people because they would be guided more by perceptions and sensations. They thus felt that the balloons and drones were highly demonstrative technologies designed to establish a presence in the public space and win votes for local officials whether or not they actually reduced or displaced crime. Despite these arguments, the remedies of protection against the technologies’ use have been dismissed and their operation has continued.

Parallel to the public debate of these legal remedies of protection, in our visits to Las Condes we find a multiplicity of sensations that complicate the affections that were sought to activate in the population. The residents stated that the balloons or drones did not necessarily provide security and often made them feel like they were being ‘tattled on’, ‘as if the devil were watching’. But the opinion that was repeated most frequently in our ethnographic visits regarding the placement of the balloons and drones was that crime had continued, showing a certain indifference to their presence. ‘Everything is still the same’, was one of the phrases most frequently uttered by the residents of the Colón Oriente area, suggesting that drug trafficking and crime continued to take place even with the presence of the balloon: ‘The people who were committing crimes were afraid in the beginning, but after a while they got used to them’ (Resident from the Colón Oriente). Furthermore, due to the daily coexistence with these technologies in the sky, people demonstrated forms of situated knowledge (Haraway 1988), recognizing certain frictions, fragilities and problems that the technologies experienced in their contexts of operation. For example, some residents pointed to blind spots, mainly the tree tops that blocked their view, or technical limitations like helium charge or battery life, gusts of wind and the height restrictions that they had to follow. Others residents criticized the discriminatory capacity of these technologies, saying that both the drones and the balloons were there ‘to protect the rich’, speculating on where their cameras are focused. This manifests the asymmetric partition of the sensible. The position of these aerial technologies speaks of a vertically defined distribution of feelings in the urban volume that establishes certain neighbourhoods and squares as more ‘dangerous’, ‘insecure’ or ‘necessary to fly over’ than others, thus reproducing socioeconomic differences and accentuating processes of stigmatization and criminalization. In sum, the multiplicity of micro-climates is not represented in public debates or even imagined by those responsible for these aerial devices, who do not consider the performativity of their located and sensitive presences.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have shown how the introduction of aerial surveillance technologies involves multi-sitedness relations, strategies and re-designs, both discursive and material. In the two cases analysed here, we can see an attempt to ‘de-militarize’ and ‘de-politicize’ these vertical technologies, performing them as ‘civilized’ tools suitable for the context of Las Condes, or even ‘Chileanized’ despite their transnational origins. The justification of the vertical regime of surveillance established by the municipality of Las Condes has been based on the supposed efficiency and greater capacity to surveil and identify ‘suspicious’ or ‘conflictive’ behaviours and spaces. However, we have tried to show that these technologies are not exclusively deployed for detecting or discouraging criminal acts, but also to intervene in citizen’s atmospheres of security.

During our research, we were able to observe how drones and balloons are used to try to activate a governmentality based on sensations, that is, to condition and produce micro-climates of security in the population. In response to the misalignment between the quantification of crime and the way the population feels, the people who promote these technologies use them not only as a tool for conduct criminal conducts, but also to affect, intervene in and conduct citizen perceptions and sensations. As such, the devices analysed here are not only handled as technical instruments, but also as mechanisms for installing micro-spheres of psycho-immunological protection in the city (Sloterdijk 2009, 2016; Klauser 2010). Or, to cite Rancière (2000), these technologies are mobilized to reconfigure the politics of the sensible, that is, seeking to impact the ‘partition of the sensible’, trying to regulate the orders of the visible, the audible, utterable, and doable. Thinking about drones and balloons as the inscription of a specific politics of the sensible – which for Rancière is the reduction of the multiplicity of the idea of consensus and normalization – implies recognizing the ontological orders that these devices seek to install, influencing ways of sensing and being in the city.

If there is a tendency to disassociate the human as a sentient entity from technologies as a simple passive reflection of human will, in this chapter we have tried to demonstrate the ways in which these technologies affects the urban environment in affective terms. In other words, our analysis allows us to situate the discussion regarding security technologies beyond our understanding of them as tools for detecting a reality ‘out there’ to be disciplined and modulated as well as a way of deploying a vertical politics of affects that reconfigure ways of feeling, living and inhabiting the urban space.

However, it is important to note that atmospheres are always fragile and ambiguous, producing themselves in an always vague and situated manner, often indifferent to efforts to design and control them at will. The intended microclimate on the part of the municipality of Las Condes inevitably coexists with varied sensations that exceeds their programme. Many residents expressed emotions that crack open the possibility of conditioning safer atmospheres, experiencing at times displeasure, violence, discrimination or indifference. The municipality’s goal of allowing residents to artificially breathe security is situated in a territory of excesses and disputes, exceeding all manner of programming. Officials can use drones and balloons to try to control the types of affects and atmospheres that are experienced in the municipality, but in their entanglements and frictions with their surroundings, these devices have the potential to exceed the intentions and wills of their operators (Simondon 1989), performing other atmospheres and modes of feeling. In this sense, the emotions and affective atmospheres produced by the drones and balloons do not depend on their intrinsic or objective qualities, but the different agencies involved. In this sense, the bodies do not only feel the qualities of the atmospheres produced by the drones and balloons differently – they also often act in unanticipated, recalcitrant manners, complicating the ways in which agents try to condition/control the urban space.

In this chapter, we sought to recognize the importance of studying the operations of atmospheric conditioning introduced by aerial surveillance technologies and the redefinitions that this suggests for surveillance and control practices in Latin American cities (Arteaga Botello 2016). We also analysed the ways in which these atmospheres are rearranged in the process of being activated by different bodies situated in specific socio-material contexts. In this sense, far from analysing the ‘security’ of these technologies as a technical effect of increasing the capacity for observation and data collection, we have tried to understand it as an event that emerges from the entanglement of bodies, varied climatic forces, materialities and sensations.