13

More than a Toy Box: Dandanah and the Sea of Stories

Artemis Yagou

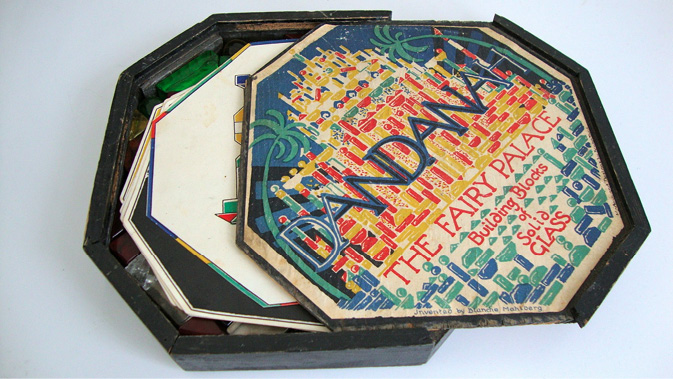

Fig. 13.1 Dandanah, The Fairy Palace (photograph by Artemis Yagou)

Name: Dandanah, The Fairy Palace – building blocks of solid glass. Date of birth: 1920. Place of birth: Germany. Shape: octagonal. Size: 278 x 277 x 40 mm. Material: wood, with a lithographed colour illustration on the lid. Colour: dark brown wood with multi-colour illustration. Behaviour: unpredictable and inspiring. Habitat: museum exhibitions, museum depots, private collections, auction houses. Distribution: eight in Germany, one in Canada, one in the United States. Similar species: Vitra re-edition (2003).

Keywords: containing, attracting, ordering, contradicting, surprising

This box is a strange specimen. It is an octagonal wooden box with a sliding door, on which a multi-colour illustration is attached; it serves as the container for a set of children’s building blocks made of glass. The box is elaborate, carefully designed, and has a complementary relationship with its fragile content. The colourful glass pieces are placed inside the container in a way specified by a ‘packing plan’ placed at the bottom of the box, facilitating their positioning and ordering. The box also contains six ‘pattern sheets’, showing possible designs to be made with the glass pieces (Yagou 2013). The geometric properties of the box and its contents are derived from the octagon and described in detail in the relevant patent (Deutsches Patentamt 1921). The patent text describes the object in question as a children’s toy made of blocks of transparent material, especially coloured glass, whose forms are based on the regular octagon, a shape of both reflective and rotational symmetry. The patent text includes no reference to the box at all and is chiefly devoted to the geometrical attributes and relative dimensions of the blocks themselves. It claims that these octagon-derived shapes make it possible to create special and unique constructions, such as bridge-like structures, which were not feasible with previous types of building blocks – a claim which is rather presumptuous and quite unconvincing.

The set of building blocks was patented in the early 1920s by Paul and Blanche Mahlberg, an art historian and his wife, respectively. However, small inscriptions on the edge of the box lid state: ‘Invented by Blanche Mahlberg’ and ‘Models and Designs by Bruno Taut’ – and indeed, the object is usually attributed to renowned architect Bruno Taut. Although the box proposed by the Mahlbergs in the patent is a regular octagon (all sides being equal), the actual wooden box has sides of unequal lengths. This may be attributed to Taut’s influence; it has been observed that the box has close geometrical affinities with Taut’s Monument des Eisens of 1913, as well as with Indian temples. The India-inspired name and cover illustration, and the six pattern sheets, are also considered to result from Taut’s input. Although there is a massive literature on Taut and his multifarious work, less is known about Paul and Blanche Mahlberg. According to one source, Paul Mahlberg was involved in the 1914 Werkbund exhibition in Cologne, where he also served as a member of the Jury (Speidel, Kegler and Ritterbach 2000). This was the exhibition where Taut presented one of his first major works, the famous Glashaus; Mahlberg was active as an architect and exhibition curator well into the post-war years (Speidel 2011). There is scant information about Blanche Mahlberg. However, she appears to be the translator of H. G. Wells’s utopian novel of 1930, The Open Conspiracy.1 In this book, Wells attempted to show how political, social, and religious differences could be reconciled, resulting in a more unified, inter-cooperating human race working towards a utopian society, and how everyone in the world could take part in an ‘open conspiracy’ which would ‘adjust our dislocated world’.2 Utopian themes such as those of Wells’s book held a central significance in the conception and design of the Dandanah. Although the connection between Taut and the Mahlbergs remains unclear and undocumented, it may be inferred that they all belonged to progressive, intellectual circles of inter-war Berlin, and shared certain beliefs. It is reasonable to assume that the Dandanah is a synthesis between the Mahlberg patent and Taut’s ideas.

The theme of utopia emerges in particular from the study of the illustration on the box lid. The geometric and ordered nature of the box’s shape appears somehow at odds with the impressionistic and exotic character of the multi-colour illustration. The latter shows an imaginary building, a ‘palace’ made of glass pieces similar to those contained in the box. The image of this building occupies the larger part of the illustration; it is flanked by palm trees and appears to sparkle and radiate light, although, curiously, there are black rays to be seen against a dark blue background behind the building. Several individual glass pieces in green and blue are shown in the lower part of the image. The illustration includes a multitude of glass pieces, certainly many more than those contained in the box: it is obvious that the construction shown on the lid may not be made with the contents of the box. The spectacular illustration is a product of imagination, a vision conveying a fairy-tale impression further enhanced by the Indian-inspired name Dandanah and the subtitle ‘The Fairy Palace – Building blocks of solid glass’. Although the toy was unnamed in the Mahlberg patent, the name Dandanah – The Fairy Palace (in English) is prominent on the box illustration and may be attributed to Taut. The use of the English language on the box cover is considered to be an indication that Taut wanted to promote the object internationally, possibly in the United States. Dandanah is an Indian word for a bundle of rods or pillars – in harmony with the box cover illustration of ‘colourful palace designs reminiscent of India and exotic places’ (Heckl 2010: 216; see also Speidel 1997; Speidel 2011). Apart from its Oriental connotations, Dandanah might also be a pun on Dada, the artistic and intellectual movement of the early twentieth century.3 This appears likely given Taut’s connections to and intellectual affinities with Dada (Boyd Whyte 2010: 178–98 and 138–141; Lodder 2006: 58; Benson 1993: 43–44). In any case, the impressive name and cover signify a clear move away from the attempted rationality of the patent descriptions and suggest a more complex picture; this paves the way for an exploration of the elaborate ideas and beliefs behind the toy.

The imaginary building on the box lid is a direct link to Taut’s utopian schemes for architecture made of glass that had preceded the creation of the Dandanah. There is a great tradition of glass architecture, incorporating a mixture of influences including Oriental philosophies and mysticism. Architectural historian Haag Bletter is keen to emphasise the long history and thoroughgoing interest in literary and architectural conventions associated with glass and crystal, and points out that such iconographic themes stretch from King Solomon, Jewish and Arabic legends, medieval stories of the Holy Grail, through the mystical Rosicrucian and Symbolist tradition down to the twentieth-century avant-garde groups (Haag Bletter 1981: 20). Taut was deeply interested in Oriental cultures and saw a harmonious relationship between the sacred and the profane in the cultures of the Orient, especially India (Boyd Whyte 2010: 56). Critic Adolf Behne amplified this in his essay ‘Wiedergeburt der Baukunst’ that Taut included in his publication Die Stadtkrone of 1919: ‘But isn’t India even greater than the Gothic? At no time has Europe so nearly approached the Orient as during the Gothic age […] Seen as a whole, however, the example of India stands high above all others as the purest oriental culture’ (Taut 1919: 130–1). Taut included photographs of great Oriental temples in Die Stadtkrone and returned to this theme enthusiastically in Ex Oriente Lux, an article published at the beginning of 1919 (Boyd Whyte 2010: 56–57). During the 1930s, Taut went to Japan where he produced three influential book-length appraisals of Japanese culture and architecture, comparing the historical simplicity of Japanese architecture with modernist discipline (Speidel 2007).

Taut’s attraction to the Orient may also be viewed in relation to the longstanding German fascination with an imagined East. It has been suggested that, Germany being ‘the middle country’, ‘a land in the middle’, or ‘the place that belonged to neither side completely’, ideas and perceptions of the East have fascinated the German mind. The political fragmentation of the country, and the problems of unification, have underpinned the need to understand and delineate ‘West’ and ‘East’. Additionally, Germany’s obsession with modernisation and progress is often juxtaposed to centuries-old Eastern traditions and the perception of the East as a lost paradise. The complex and ambiguous process of Germany’s adaptation to its own modernisation and nation-building has nourished the appeal and study of the distant Other, particularly in scholarly works of lyric and fantasy, and may be examined within the wider context of Orientalism (Roberts 2005).

Another significant dimension of the Dandanah box is technology-inspired. In the beginning of the twentieth century, not only was glass technology presented as a potential agent of change in engineering and architecture, but glass was also considered by Taut and others to be a metaphor for purity, innocence, and hope. Often, the call for light in buildings represented a symbolic dimension of a spiritualised, utopian architecture. Taut believed in architecture as a regenerative force in society at large, and that, through its power to dematerialise, glass lifted architecture above materialism, to a higher, spiritual level. In addition to the use of glass, many of the visionary architectural proposals of the early twentieth century emphasised the physical and plastic qualities of buildings through colour. Taut wrote that ‘the glowing light of purity and transcendence shimmers over the carnival of unrefracted, radiant colours. […] like a sea of colour, as proof of the happiness in the new life’ (Taut 1919: 69). Commentators have also attempted to historicise and theorise the remarkable fascination with crystals found in contemporary art theory and practice. In aesthetics, science, and art production, the crystal embodies intimations of transparency, of vitalistic transformation, or of a purist stability; it powerfully articulates a line or gradation between the organic and inorganic (Cheetham 2010).

Although Taut intended to produce Dandanah commercially, this project did not materialise. Only a few copies were produced, which have become cherished museum objects and much sought collectors’ items today. In the early 2000s, the Swiss company Vitra issued a reproduction of the Dandanah; the box lid was, however, only a simplified version of the original, as the Indian glass palace illustration was only shown on the cover of the enclosed leaflet.4 The lid of the Vitra re-edition of the object was thus plain, compared to the original; the ‘oriental’ and mystical associations were removed from the exterior, turning the box into a sleek item compatible with a fashionable and perhaps more marketable modernism. One might argue that the Vitra re-edition expresses an attempt to control and modify the emotional content of the artefact and, in a sense, to rationalise it. Thus, the Dandanah becomes more appropriate to a clientele attracted by a minimalist, functionalist image of modernism, rather than by its more mystical aspects. The Vitra edition promotes a selective modernism, compatible with the company’s wider strategy of reproducing and marketing modernist icons. The price-tag made the object inaccessible to all but a minority of consumers. What impression would the Vitra Dandanah give, when laid out on a contemporary living-room table? Arguably, it would suggest a lot about the owners’ wealth, taste, and status. The re-edition is not meant to be a toy for children, but rather a decorative object or home accessory to be flaunted and appreciated by adults (Yagou 2013).

A further contradiction emerges in relation to the assumed users of the original object. Building blocks are supposed to be made for children, but they are designed by adults and express their preoccupations, concerns, and fantasies: these are projected onto children and suggest desired ways of behaving. In the case of the Dandanah, the illustration on the box’s lid, the exotic name, even the unusual shape, generate great expectations; they fire the imagination and underpin a complex relation between the box’s appearance and the content, the actual plaything. The highly geometric nature of the glass pieces, and the discipline required to use them safely (given the unusual and fragile nature of the material), somehow contradict the expectations created by the lid illustration. By hiding and selectively revealing, the box preoccupies the user and shapes to a great extent the object’s identity. This is particularly significant if one thinks of the object as a product in the market, where the box or container becomes ‘packaging’ that often drives the purchasing act. In the case of playthings, the purchaser – for example, a parent – is more often than not different to the end-user – i.e. the child. Sometimes though, the adult purchaser also becomes a user by playing together with the child or children. In any case, the reality of play in everyday life is rarely documented; children do not normally leave records of their actions. Activities of daily life in domestic settings, and especially children as historical actors, usually remain in the shadow of adult activities. One wonders how children actually used this box and how they played with the glass pieces: how did the adult utopian fantasy, expressed so powerfully by the box lid illustration, influence the reality of children’s play? Furthermore, the exuberant illustration is at odds with the highly ordered interior, which affords a limited number of solutions for packing the pieces, thus requiring disciplined action by the player after the play is over. Given the fragile and potentially dangerous nature of the glass pieces, it is assumed that proper positioning and safe packing of the pieces would be indispensable after playing. Despite the fancy cover illustration, there is a clear antithesis between the formalism of the austere octagon and the presumed spontaneity of free play activity.

Such thoughts emerge from the study of this unusual object and imply the fascination it generates as the focus of design discourse. Design discourse deals with artefacts, the meaning of which remains fluid and un-fixed, continuously arising in social interactions based on language. When objects of design are treated as language-like, interactive meanings and the practices they inform render materiality and technology subordinate to what people see. Unravelling such meanings may be achieved by, among other things, expanding design spaces through systematic reframing of existing artefacts. In this process, meanings emerge or disappear and thus new, unexpected and still unimagined meanings may be produced (Krippendorff 2006, 2011). Research along these lines generates a wealth of links to different as well as interconnected themes. In this vein, looking at the Dandanah from the perspective of its container may lead to alternative histories of the object. It could be the starting point to a ‘sea of stories’, a reference to a children’s novel by Salman Rushdie, where the author speaks of

[…] a thousand thousand thousand and one different currents, each one a different colour, weaving in and out of one another like a liquid tapestry of breathtaking complexity; […] these were the Streams of Story, that each coloured strand represented and contained a single tale. Different parts of the Ocean contained different sorts of stories, and as all the stories that had ever been told and many that were still in the process of being invented could be found here, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was in fact the biggest library in the universe. And because the stories were held here in fluid form, they retained the ability to change, to become new versions of themselves, to join up with other stories and so become yet other stories. (Rushdie 1993: 72)5

The Dandanah, almost a century old, is nowadays a rare and precious item. It resides quietly in museum exhibitions or museum depots, or lies as a treasured object in private collections and is sold for high prices at auctions. Formerly used by children as a toy – perhaps even mistreated, as the worn-out box and several damaged glass pieces indicate – it is now handled delicately and carefully preserved in museums or private collections. The box itself bears visible signs of wear, revealing traces of the people who have handled and used it over the years. Its material specificity in the present brings to the fore ideas, dreams, illusions, and actions of people long gone. Research on the Dandanah has illustrated the continuing allure of larger-than-life utopian themes; it has also pointed to the power of small things to challenge, inspire, and delight. The Dandanah box may be a small piece of material evidence, and no more than a detail in the history of design, but it is rich and replete with potential for different narratives. It is a mysterious and contradictory item, but also exciting and inspiring. This short essay has demonstrated that, by using the box of the Dandanah as a starting point, it is possible to discuss a variety of issues related to society and technology, to learn, reflect, and take pleasure in discovering aspects of human experience.

On a more general level, object-based museum research highlights the complex existence of objects by revealing their multiplicity and by demonstrating the ways in which they may act as pointers to a whole range of sociocultural issues. The development of object-based research could be of major importance in a culture that depends on being perpetually renewed, as this type of research adds value to the material repository and enables diverse stakeholders to reflect on society, ask new questions, formulate new answers, and in these ways contribute to shaping desirable futures. The richness of objects may be uncovered by historical research and may form the basis for a range of engaging museum activities. Exploring objects like the Dandanah may disclose a treasure of histories and potential meanings; the fascination of learning from mundane boxes is just one of these meanings.

notes

1 Published in Berlin by P. Zsolnay in 1928 under the German title Die offene Verschwörung: Vorlage für eine Weltrevolution, and republished as Die offene Verschwörung: Aufruf zur Weltrevolution in Frankfurt by Ullstein in 1986, as well as in Vienna by Zsolnay in 1983. The Open Conspiracy was published in English in 1928. A revised and expanded version followed in 1930, and a further revised edition in 1931, titled What are we to do with our Lives? A final version appeared in 1933 under its original title (Yagou 2013).

2 H.G.Wells, The Open Conspiracy, Chapter 2, gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1303661h.html#chap02 [accessed 21 November 2018]

3 Dada or Dadaism, a cultural movement that began in Zurich, Switzerland, during World War I and peaked between 1916 and 1922. Born out of negative reaction to the horrors of war, this international movement rejected reason and logic, prizing nonsense, irrationality, and intuition. The movement involved visual arts, literature, poetry, art manifestoes, art theory, theatre, and graphic design, and rejected the prevailing standards in art. Dada intended to ridicule the meaninglessness of the modern world as its participants saw it. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dada> [accessed 2 October 2018]

4 A copy of the Vitra re-edition of the Dandanah is kept in the Badisches Landesmuseum, Karlsruhe.

5 Rushdie, Salman, Haroun and the Sea of Stories, Puffin, 1993. The title of this essay alludes to this book, a phantasmagorical story that begins in a city so old and ruinous that it has forgotten its name. Haroun and the Sea of Stories is a novel of magic realism, an allegory for several problems existing in society today, especially in the Indian subcontinent. The connection between this novel and the Dandanah is in a sense arbitrary, but also intriguing and perhaps intellectually fertile. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haroun_and_the_Sea_of_Stories> [accessed 2 October 2018].

References

Benson, T. O., ‘Fantasy and Functionality’, in Timothy O. Benson, ed., Expressionist Utopias: Paradise, Metropolis, Fantasy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

Boyd Whyte, I., Bruno Taut and the Architecture of Activism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Cheetham, M. A., ‘The Crystal Interface in Contemporary Art: Metaphors of the Organic and Inorganic’, Leonardo, 43.3 (2010): 250–56.

Deutsches Patentamt, Patentschrift 340301, 7 September 1921.

Haag Bletter, R., ‘The Interpretation of the Glass Dream: Expressionist Architecture and the History of the Crystal Metaphor’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 40.1 (1981): 20–43.

Heckl, W. M., ed., Technology in a Changing World: The Collections of the Deutsches Museum (Munich: Deutsches Museum, 2010), pp. 214–15.

Krippendorff, K., The Semantic Turn: A New Foundation for Design (Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis, 2006).

——, Designing Design-Forsch-ung, not Re-search, Keynote speech, Conference on Practice-Based Research in Art, Design & Media Art, Bauhaus-University Weimar, 1–3 December 2011

Lodder, C., ‘Searching for Utopia’, in C. Wilk, ed., Modernism: Designing a New World 1914–1939 (London: V&A Publishing, 2006), pp. 22–40.

Roberts, L. M., ed., Germany and the Imagined East (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2005).

Rushdie, S., Haroun and the Sea of Stories (London: Puffin, 1993).

Said, E., Orientalism (New York: Vintage, 1979).

Speidel, M., ‘Der Glasbaukasten von Bruno Taut’, Unpublished manuscript (Munich: Deutsches Museum, 1997).

——, K. Kegler and P. Ritterbach, eds, Wege zu einer neuen Baukunst, Bruno Taut ‘Frühlicht’-Konzeptkritik Hefte 1–4, 1921–1922 und Rekonstruktion, Heft 5, 1922 (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2000).

——, ed., Bruno Taut. Ex Oriente Lux: Die Wirklichkeit einer Idee (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2007).

——, ‘Stadtkrone und Märchenpalast. Zum Glasbauspiel von Bruno Taut’, Unpublished manuscript (Karlsruhe: Badisches Landesmuseum, May 2011), reproduced in Yagou (2013).

Taut, B., Die Stadtkrone (Jena: Diederichs, 1919).

Yagou, A., ‘Modernist Complexity on a Small Scale: The Dandanah Glass Building Blocks of 1920 from an Object-Based Research Perspective’, Deutsches Museum Preprint, 6 (2013) <http://www.deutsches-museum.de/forschung/publikationen/preprint/> [accessed 2 October 2018].