27

Cardboard Box: The Politics of Materiality

Maria Rentetzi

Fig. 27.1 A homeless man sleeps inside a cardboard box on Ermou street in central Athens in the early hours of Sunday, 28 June 2015 (source: Associate Press/Daniel Ochoa de Olza)

Material: cardboard paper, that is, heavy-duty paper consisting either of a single thick sheet of paper or multiple corrugated and non-corrugated layers. Size and shape: it is produced in a variety of sizes and shapes. Origin: we first come across its modern broad commercial appearance in the early nineteenth century in the US. Habitat: it often appears sleek and decorated in store windows; loaded with all kinds of objects in attics, storerooms, and warehouses; orderly arranged in archival depositories; flattened and crumbled on pavements; greasy and worn out in storefronts. Behaviour: attractive and seductive when performing its original function; protective when it appears as a home of the homeless person; political when appearing in newspapers and TV news. Migration: from packaging industries, window stores, and commercial warehouses to pavements and the open urban environment.

Keywords: seducing, persuading, commercialising, modernising, storing, packaging, protecting, shipping, housing, ordering/disordering, displacing, huddling

I have a strange interest in all boxes. I used to collect tin and paper boxes, most of the time empty ones, just because I enjoyed the graphics on their exterior. An odd habit. A close friend of mine was courageous enough to suggest that Freudian theory might hold the answer. In his general introduction to psychoanalysis, Freud discusses the symbolic interpretations of dream elements. The great majority of symbols in the dream, he argued, are sex symbols. Boxes find a prominent place there. ‘The female genital is symbolically represented by all those objects which share its peculiarity of enclosing a space capable of being filled by something – viz., by pits, caves, and hollows, by pitchers and bottles, by boxes and trunks, jars, cases, pockets, etc.’ (Freud 1920). I was not sure what to make of this and so I pushed it under the carpet for a long time – that is, until boxes began turning up in my scientific work (Rentetzi 2011) and, more persistently, in my daily life. I always thought of boxes as objects that enclose other objects. But my recent daily experience proves that boxes have also been extensively used for enclosing human beings. I’ll begin with this.

I live in Athens, Greece, and I love walking on Ermou Street, a once-bustling pedestrian destination with an impressive history and some of the best coffee shops in the world. A symbol of the city’s modernisation, it was designed in 1834 by Stamatios Kleanthis and the court architect Eduard Schaubert. It served as the base of an isosceles triangle with its peak at the Royal Palace – today’s Greek Parliament – and has been a symbolic geometric apex of power since then. Ermou Street was named after Hermes, the Olympian god and patron of commerce, and served from the early days as the city’s upscale shopping heaven.

The idea of modernity that Bavarian King Otto and his royal court tried to impose on Greece, although at odds with the locals, sought to politically incorporate the country into modern Europe. Architects and city planners were called upon to do part of this job. The report by Emmanuel Manitakis, a general in charge of public works in Greece, on the progress of Athens’ reconstruction in 1866 is indicative of this intent. The report refers to Athens’s ‘large and well-aligned streets, beautiful houses built according to Italian taste, the oldest of which dates to 1834, numerous public structures and its population which, in its manner of dressing, living, and thinking, is to such a degree similar with the great family of civilized nations of Europe’ (quoted in Bastea 2010: 30).

Indeed, throughout the nineteenth century, Ermou Street, with its 360 shops selling goods such as hats, shoes, stationery and jewellery, embodied the notion of modernity that Manitakis had in mind. A destination for the royal family and the upper class, Ermou remained so even during the interwar period, monopolising women’s fashion and hosting some of the most extravagant artists of the period. Among them was Nelly, the well-known Greek photographer, who set up her studio in Ermou Street in 1924. Interestingly, the street never lost its flavour and flair for exclusive shoppers. In 1997 it was turned into a pedestrian thoroughfare, becoming the city’s most expensive commercial street and a colourful cultural destination. Along with New York’s Fifth Avenue, Paris’s Champs-Élysées, and Milan’s Via Montenapoleone, it appeared in the list of the ten most expensive streets in the world. Yet in 2009, because of the financial crisis that hit the country, Ermou began losing its glamour. Recent statistics show that two in ten of the street’s ground level stores are vacant.

Today I take fewer walks in the area, but not because I no longer enjoy shopping. I never did anyway. Rather, I caught myself feeling sad as I watched the transformation of the cardboard box from a symbol of commercial prosperity to an icon of financial depression.

After Greece’s first bailout in 2010, unemployment rocketed from 9.5% in 2009 to 17.7% in 2011, and finally to 25.2 % in 2015 (The World Bank; Eurostat). As I write this, Greece has the highest unemployment rate of all EU Member States. A massive wave of layoffs that started right after 2009 led many to unemployment and soon to homelessness. In addition, Greece’s social infrastructure collapsed from the impact of the most brutal austerity measures that a European country has seen since World War I. When limited and meagre unemployment benefits expire, people are left with no income and no right to health insurance. Until the crisis started, homelessness was relatively unusual in a country of strong family ties. In 2009 there were just over 7,000 homeless people in Athens. Today, there are more than 20,000, among them even middle-class people who lost their jobs and were unable to pay rent.

As Marianella Kloka, advocacy officer of PRAKSIS, which works with Doctors without Borders, reported

I could never imagine there would be so many homeless people in the center of Athens. There used to be a very small number of people who lived in the streets all their lives. Now I see young people in the streets, I see people my age, around 40. They are on the street begging or sleeping. (World Socialist Website 2015)

Greek and international newspapers report on how the new homeless find shelter during warm summer nights and cold, rainy ones in makeshift homes. Photographers such as the Spaniard Daniel Ochoa de Olza from the Associated Press, or the Greek Yannis Behrakis from Reuters, have extensively documented what has become part of our everyday lives: people huddled on flattened cardboard boxes or sleeping inside them, as others sleep wrapped up in blankets in entrances and in arcades all over the city centre. Despite its historical and glamorous past, Ermou Street was among the first to be populated by the homeless and their cardboard boxes. Indeed, these cardboard boxes now characterise a particular urban aesthetic of homelessness.

The History of the Cardboard Box

The cardboard box goes largely unappreciated. We usually associate it with changing locations and residences. We use it for shipping products, storing our books, packaging our food and an endless number of commodities, preserving our personal mementos, archiving our research projects, holding children’s toys in order to keep their rooms tidy. Often, we break up the boxes that arrive home as packaging. We flatten them, convinced as we are by the recycling industry that this is a way to reduce our environmental footprint. And indeed, the environmental burden is not trivial. For example, in the United States, one of the most industrialised countries, over 90% of goods are packaged and shipped in cardboard. Statistics inform us that in the United States and Canada there are approximately 1500 corrugated packing plants and over 400 million tons of cardboard are produced worldwide. The demand for cardboard as packaging material has turned the cardboard box into the single largest waste product in the developing world. It has been estimated that over 24 million tons of cardboard are discarded each year.

A symbol of industrialisation and commercialisation, the cardboard box also reflects recent changes in the geopolitics of power. Since 2009, China has taken the lead in cardboard manufacturing, with the United States trailing by some margin. In 2009 China produced a little over 86 million metric tons of paper and cardboard, and the United States almost 72 million tons. Yet by 2013 had China reached 105 million tons compared to the United States’s 74 million. These numbers reflect China’s rapid growth and its attempt to build the most extensive global commercial market.

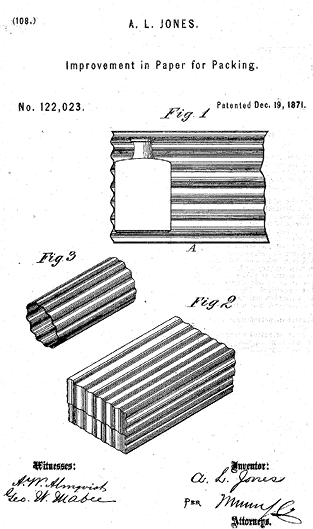

Cardboard boxes have always been associated with the rise of consumerism and the need to both protect and promote new consumables and thus new desires. The story goes that the first commercial cardboard box package design was created in England in 1817 to hold a German game called ‘the Besieging Game’, inspired by armed forces and war (Groth 2006: 7).1 Paper and cardboard remained luxuries until the end of the century when Albert Jones of New York filed a patent in 1871 for the ‘improvement in paper for packing’. He proposed to turn corrugated paper into packing boxes instead of wrapping for vials or bottles. According to the patent,

The object of this invention is to provide means for securely packing vials and bottles with a single thickness of the packing material between the surface of the article packed; and it consists in paper, card-board, or other suitable material, which is corrugated, crimped, or bossed, so as to present an elastic surface by reason of such corrugated, crimped, or bossed surface, as will be hereinafter more fully described (Jones 1871).

The objective was to protect the content of the box and prevent the delicate glass products from breaking. In these early days, box making was an intensive labour craft that was carried out by hand and catered mainly to hat and shoe factories. However, the most efficient cardboard box was created by the American lithographer Robert Gair a few years later. American printers were among the earliest paper-based packaging makers. Gair saw potential in the use of paper packaging for marketing household items, but the invention of the actual cardboard box was serendipitous. Gair, who was already in the paper bag business, had set up his first paper factory in 1864 in New York, and soon mechanised his production. In 1879, one of his workers accidentally cut through 20,000 paper seed bags by setting up a type ruler too high. This has been described as the event that inspired Gair to develop an efficient mechanised method to produce folding cardboard boxes by printing, cutting, and creasing cardboard in one go (Twede et al. 2015). The major advantage of his invention was that boxes could be stored flat and easily transported – the first ready-to-assemble folding boxes. With this modification Gair was able to cut 750 sheets an hour on one press, something that had previously taken a day. Gradually he introduced the direct printing of cartons, facilitating both branding and advertising.

Fig. 27.2 Albert Jones’s patent for the improvement in paper for packing, 1871 (source: United States Patent and Trademark Office, patent number 122023)

By 1900 all kinds of products were already being shipped in corrugated paper boxes. Soon, Gair built up a paper and packaging empire. His first clients were mainly tea, tobacco, and cosmetics companies. His big break, though, came when Nabisco, the National US Biscuit Company, decided to pre-box the Uneeda Biscuit, placing a two million-unit order in 1898. To respond to such high demand, Gair built two six-story brick factories in Brooklyn, and in 1909 he commissioned the construction of one of the earliest industrial buildings in reinforced concrete. As he bragged in one of the company’s advertisements,

From its housing in the little loft in down-town Manhattan, our business has expanded to occupy a large group of modern steel and concrete buildings on the Brooklyn waterfront. We have recently further enlarged our facilities by the acquisition of the three paper mills… These plants, located on tide-water, offer in combination with our Brooklyn factory unusual resources to meet the needs of our clients. (Robert Gair Company 1920: 7)

But while Gair was building his paper empire, working conditions in many paper box factories were below par. Already by 1910, during the thirteenth US census, New York dominated the country’s fancy- and paper box manufacture with 315 establishments and close to 13,000 workers. In industries that produced folding boxes, such as Gair’s, the majority of tasks were performed by a large die-cutting and creasing machine, which cut and creased the entire box form in one piece. In many cases, trade names, design, and descriptions were printed on the pasteboard prior to cutting and creasing. Women, mostly young girls, worked in the printing department, lifting the uncut sheets and feeding them into the press. A report published in 1915 by the Commonwealth of the State of Massachusetts on the wages of women in the paper box industry revealed the occupational risks of working in these factories. More than 43% of those injured were women, the majority under thirty years old. Similar reports on the New York paper box industry for 1913 and 1914 showed that women were paid 40% less than their male colleagues. With little education, and under social pressure to leave work after marriage, women were destined to earn less for more work (Vitaliano 2009; The Commonwealth of the State of Massachusetts, Minimum Wage Commission 1915).2

An extended review produced by the Department of Labor for the State of New York in 1928 was revealing of the gender differences in the paper box industry, even during the interwar years. Men represented a third and women two-thirds of all the workers in the industry. While fewer in number, however, men were employed in better and more well-paid positions. They were exclusively employed in box shipping and transportation, and in the mechanised cutting department, as highly-skilled machinists who repaired, set up, and maintained the machines. Women were largely employed in finishing and manual work. Work conditions were poor and had already led to a major strike in 1927, an event that triggered the report. In short, physical working conditions, plant hours, rates, and salaries were particularly controversial issues. Among the outstanding facts mentioned in the report were cleanliness and sanitary arrangements: ‘Workrooms were dirty and there was inexhaustible neglect in regards to sanitary arrangements. Cellars were often used as cutting rooms, exposing workers to cold and dampness in the spring and fall and to excessive heat from the boilers in winter’ (Hamilton 1928: 8).

Gender differences in the industrial production of goods weren’t and aren’t news, but they have been an intimate part of the commercialisation of the modern world and the triumph of capitalism. The gender profile of the paper industry did not really change even after World War II. By 1940, the Paper Box Manufacturers Association ran 865 shops, most of which were located in the north-eastern part of the country. It is telling that the industry employed 40,000 workers, of whom 75% were women. In several New York shops, the few men and native-born American women who were employed did the skilled work, while immigrant women, mainly from Italy, posted labels or stuffed finished boxes.

From Symbol of Commercial Prosperity to Icon of Financial Depression

‘Changing the buying habits of a nation: How the individual package has grown from an experiment to an essential in modern business’ was the telling title of a text and image advertisement that the Robert Gair Company placed in The Sun and New York Herald in 1920. With the growth of consumerism came the rise of packaging, which in turn changed consumer habits. There is nothing intrinsically surprising about this development. After all, packaging economies provide a context for understanding such a correlation. Until the end of the nineteenth century, to manufacturers and retailers in the US, packaging meant tying up a parcel with wrapping paper and string. Merchandise was sold in bulk in makeshift packages and then transported home. As merchandise changed in the early twentieth century, however, so did the packaging of commodities. Using a container to convey the product to the end consumer reduced handling and transportation costs. Packaging reinforced by publicity and advertising induced consumers to pay a higher price for goods and served to identify a product by its brand name, and thus facilitate sales. Gair’s invention gave manufacturers the opportunity to take control of the market. Products were pre-packaged in the factory and not in the store, and thus direct advertisement became possible in magazines and newspapers. The cardboard box was elevated to a symbol of the American commercial boom.

In general, this was the time when new materials such as glazed paper, aluminium foil, glass containers, and folding cartons influenced the ways products were marketed. Political factors, such as the eighteenth amendment that prohibited the consumption of alcohol and came into effect in 1920, led to novel uses of glass beyond the manufacture of liquor containers (which was no longer a profitable option). As the economic depression eased, and the world of business and technological improvements boosted, the use of colour and the shaping of materials offering a wider range of choices in package design.

In the midst of the Great Depression, folding carton manufacturers established the first packaging association in 1929, known later as the Folding Paper Box Association in America (FPBAA). In 1933, thirteen folding cartoon manufacturers set up the first Code of Fair Competition regulating work in the paper box industry. Yet women were still paid five cents per hour, when the Code suggested a minimum wage of forty cents (Paperboard Packaging Council).

By the mid-1930s, the packaging industry had grown stronger as it became clear that container-design clearly affected merchandising. At that point, package manufacturers were in control of the market. In 1936, five years after the first Packaging Conference in New York, Irwin Wolf, the vice president of the American Management Association, proclaimed that packaging was ‘a vital factor’ required to move stocks and that packaging had undergone ‘revolutionary changes’ in development within the past five years (Wolf 1936: vii). Kellogg’s is a good example here. In a full-page advertisement in LIFE on 12 December 1938, the company urged its customers to collect the package-tops of Kellogg’s Rice Krispies, a ‘real-rice cereal’. The company’s customers dutifully collected twenty such package tops and mailed them with $1.40 to receive framed, full-colour copies of six illustrations featuring characters such as Humpty Dumpty and Pumpkin Easter. The packages themselves had become traded goods, and market research into consumers’ preferences fuelled the packaging industry. As package designer Egmont Arens later argued, ‘mass production and changing ways of living have elevated [package] design to a merchandise science’ (Arens 1952, 153).

As the American economy stabilised in the 1950s and 1960s, and technology advanced, the cardboard box packaging industries tried to streamline production. The aim was to use statistics, marketing information, and management tools in order to improve their business. Their lavish annual meetings were living proof of the booming packaging industry (Figure 27.3).

Fig. 27.3 American singer Wyoma Winters was named Miss Folding Paper Box 1952 at the annual Folding Paper Box Association of America (source: aperboard Packaging Council)

Ironically, as the cardboard box was elevated to the status of a symbol of America’s economic success, commercialisation, and industrialisation, it also signalled the increase in the numbers and the visibility of homeless people in urban areas. Closely connected to, but at the same time a counterpoint of, the country’s economic transformation, the cardboard box served as a shelter and precious possession of the American homeless person (Figure 27.4).

Fig. 27.4 An elderly homeless African-American woman pushes a pram with a large cardboard box on top (source: Scurlock Studio Records, ca. 1905–1994, Archives Center, National Museum of American History)

Throughout the twentieth century urban homelessness had a particular aesthetic, one that to social researcher Myrto Tsilimpounidi ‘seems to reinforce the imbrication of market forces within its very conditions; with homeless men and women often purloining shopping trolleys from super markets in which they wheel their belongings.’ Instead of carrying purchased goods from supermarkets to apartments, these trolleys hold the ‘vestiges of home, becoming piled high with fresh cardboard boxes and throwaway items’ (Tsilimpounidi 2015). In most cases, the homeless person’s home is a cardboard box, a makeshift shelter on the pavement, in front of the shop windows of major pedestrian shopping areas. Paradoxically, the cardboard box – the waste of our commercial world – is recycled in such a way as to make visible the disorder in our societies, the faults of capitalism.

I look again at Daniel Ochoa de Olza’s picture of the homeless man sleeping in front of a chain store on Ermou street. My friend’s suggestion begins to make sense. I walk down Ermou Street less often because the house of the homeless – the crumpled cardboard box – is a womb-like enclosure that upsets my sense of security and eats away at my trust in order. It reveals the fragility of our social world and the fluidity of its boundaries. I might be next. This is why I/we should probably go back and resume our walks on Ermou Street, piecing together a new order, a new kind of humanism that eliminates the cardboard box from sidewalks and reveals the inhuman politics of materiality.

Notes

1 An example of this game can be found in Victoria and Albert Museum in England, see <http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O25924/the-game-of-besieging-das-board-game-unknown/>

2 See also The Commonwealth of the State of Massachusetts, Minimum Wage Commission 1915.

References

Arens, E., ‘25 Years of Progress in Package Design’, Modern Packaging (March 1952): 152–59.

Bastea, E., ‘Athens’, in E. G. Makas and T. D. Conley, eds, Capital Cities in the Aftermath of Empires (New York: Routledge, 2010), pp. 29–44.

Eurostat, ‘Unemployment statistics’, in Eurostat Statistics Explained, <http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Unemployment_statistics>.

Freud, S., An Introduction to Psychoanalysis (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1920), <http://www.bartleby.com/283/10.html>.

Groth, C., Exploring Package Design (Clifton Park, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning, 2006)

Hamilton, J., ‘The Paper Box Industry in New York City’, Department of Labor, Special Bulletin, 154 (1928): 8.

Jones, A., ‘Improvement in Paper for Packing’, U.S. 122023 A Patent, 1871.

Paperboard Packaging Council, ‘PPC: Over 80 Years of Excellence’, <http://paperbox.org/About-PPC/PPC-History>

Rentetzi, M., ‘Packaging Radium, Selling Science: Boxes, Bottles and Other Mundane Things in the World of Science’, Annals of Science, 68., 3 (2011), 375–99.

Robert Gair Company, ‘Changing the Buying Habits of a Nation’, The Sun and New York Herald, Thursday, 15 April 1920.

The Commonwealth of the State of Massachusetts, Minimum Wage Commission, ‘Wages of Women in the Paper Box Industry’, Bulletin 8 (September 1915).

The World Bank, ‘Unemployment, total’, in The World Bank Database, <http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS?order=wbapi_data_value_2011%20wbapi_data_value%20wbapi_data_value-first&sort=desc>

Tsilimpounidi, M., ‘Topographies of Illicit Markets: Trolleys, Rickshaws and Yiusurums’, in M. Zaroulia and P. Hager, eds, Performances of Capitalism, Crisis and Resistance Inside/Outside Europe (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015), pp. 56–76.

Twede, D., et al., Cartons, Crates and Corrugated Board. Handbook of Paper and Wood Packaging Technology, 2nd edn (Lancaster, PA: DEStech Publications, Inc., 2015).

Vitaliano, D., ‘Gender Wage Differences and Human Capital in the Early Twentieth Century: The Case of the Paper Box Industry in New York’, in Review of Economics of the Household, 7 (2009), pp. 179–88.

Wolf, I., ‘Foreword’, in James Rice, ed., Packaging, Packing and Shipping (New York: American Management Association, 1936), pp. vii–viii.

World Socialist Website, ‘I could never imagine so many homeless people in Athens’, World Socialist Web Site, 9 March 2015, <http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2015/03/09/gree-m09.html>