6

Slide Box: How to Stock Some Thousand Cancer Cases

Ulrich Mechler

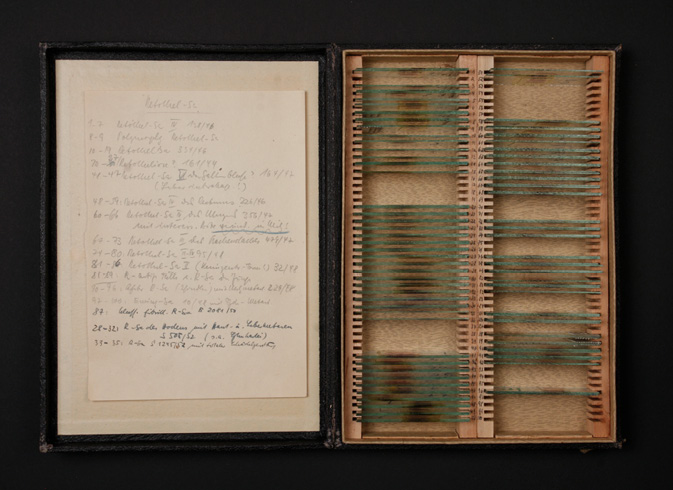

Fig. 6.1 Microscopic slide box from the collection of German pathologist Karl Lennert

Box: slide box. Appearance: functional, mostly unadorned; if old, often worn out. Size: different sizes, but usually (like this one) about 19.5 x 27.5 x 3.5 cm. Habitat: not far from microscopes, life sciences research institutes, medical facilities (particularly pathology), archives, sometimes museums. Origin: nineteenth century, probably England or Germany. Migration: spreading from botany over the entire field of life sciences. Status: still widespread.

Keywords: collecting, archiving, ordering, classifying

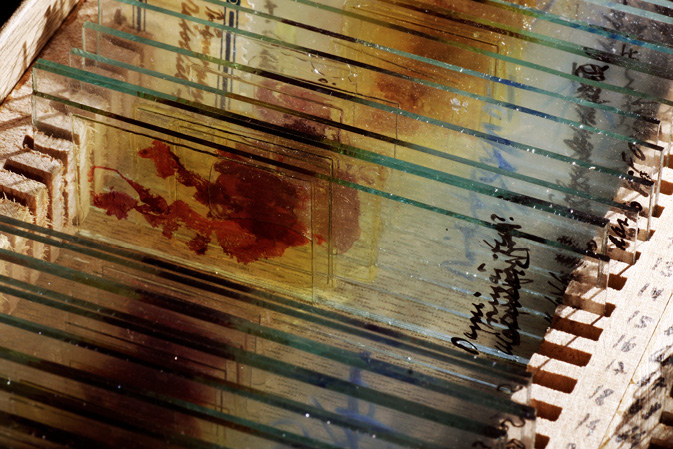

Our box dates back to the 1940s and is designed and manufactured for a single specific purpose. It is a storage container for microscopic – more specifically, histological – specimens, briefly called slides. Our box contains 124 of them. Histologic slides are the ubiquitous working tools of pathologists when working with a microscope, which is what most of them do most of their time. Histologic slides preserve human tissue samples, either taken post-mortem and examined in the context of an autopsy of deceased patients, or, more commonly nowadays, taken intravitally during the diagnostic examination of patients. Removed during a surgical procedure, the tissue sample undergoes elaborate laboratory processing in which it is artificially changed and preserved. After the tissue has been dehydrated, it is embedded in paraffin. Next, a so-called microtome is used to cut 4-micrometer-thick tissue sections which are then mounted on a glass microscope slide, usually measuring 26 x 76 mm. The section is then stained and sealed with a cover slip. Under the microscope, pathologists examine the slide and search for minute anomalies in the tissue pattern that they can correlate with a disease entity. Particularly in the case of malignant tumour-forming diseases, the histological examination is a central component of the diagnosis; a given tumour can be specified (by a process called ‘typing’), and in many cases, to the patient’s relief, a true malignant process can be excluded.

Histopathology, the science of pathologically altered tissues, developed in the last third of the nineteenth century. It changed our knowledge of diseases fundamentally. In the twentieth century it became an important branch of diagnostics, with greatly increasing significance for patients. This development continues today: histopathology strives for a theoretical understanding of diseases, their causal pathophysiological mechanisms, and their manifestations and effects on the organs, tissues, and cells. In pursuing this goal, histopathology is always dependent on the examination of specific individual cases of illness. Theoretical disease research and practical application in diagnostics are thus intertwined, and it is from this epistemic tension that our box has emerged. Tracing the emergence of this specific type of box in the nineteenth century opens an insight into the material culture of a specific ‘thinking collective’ (Fleck 1935). Exploring the history of our individual box deepens this insight through the example of a particularly intricate chapter of disease research in the twentieth century. The practice of knowledge production in histopathology is substantially shaped by the medial qualities of its mundane objects, including slides.

Our slide box belongs to the extensive collection of microscopic slides amassed by the German pathologist Karl Lennert (1921–2012) over the course of his entire professional life. Karl Lennert is considered one of the most outstanding scientists of German post-war medicine. His special research interest was the diseases of the blood-forming organs: bone marrow, spleen, and especially the lymph nodes. Lennert gained international recognition in the 1970s for developing a classification of the so-called non-Hodgkin lymphomas, a subgroup of the malignant lymphomas, the tumours of the lymph nodes. The diagnosis of these diseases has always been considered particularly complicated, while corresponding problems also shaped their theoretical and systematic understanding. For many decades, the question of how to classify lymphomas was a particular problem in tumour pathology. Emblematic of this situation is the laconic and oft-cited comment of the Australian pathologist Rupert Allen Willis that ‘Nowhere in pathology has a chaos of names so clouded clear concepts as in the subject of lymphoid tumors’ (1948: 760).

Karl Lennert’s collection contains around 10,000 cases of diseases that show lymph node infections, mostly malignant lymph node diseases. Each case is a material-semiotic ensemble, containing strictly selected and highly compressed clinical information and, of course, some slides (usually four, sometimes up to thirty). The oldest cases date back to the 1940s, when Karl Lennert was a student. He added the latest in the 1990s, years after he retired. Lennert’s collection reflects half a century of history of pathology. Considered together, the cases bear witness to rapidly evolving laboratory techniques and a gradually deepening biological understanding of lymphoma disease. This is reflected in changing disease names that resulted from new knowledge, definitions, boundaries, and concepts of disease. During this period of post-war medicine, not only the diagnosis of lymphoma changed, along with all its methodological and epistemological conditions, but also disease research itself, its infrastructure, and its socio-technical and institutional conditions. With his lifelong passion for meticulous collecting, Karl Lennert appears more like a scholarly type of the nineteenth century; nevertheless, he was a forerunner of modern biomedical disease research in Germany.

Lennert’s collection also reflects his biography as a scientist. It starts with an aesthetic fascination that was developed into a profound expertise and finally flowed into a research programme pursued for decades. Lennert’s collection was the central tool of his entire work. And the principle of success of this work was his detailed familiarity with the histological morphology of the disease, its variants, stages, and varieties. This knowledge, in turn, was based on his meticulous and dogged collection of cases that he considered notable. Again and again, Lennert revised these cases, compared them with others, and related them to current research results. The manner in which the collection is organised is therefore by no means uniform; indeed, the collection can be considered an adjustable research instrument, whose functionalities were adapted to meet changing conditions and objectives.

One such adaptation of the collection to new requirements will be outlined in our focus on a single box, which will show how Lennert aligned his research interests to the demands of modern postwar pathology and its strictly clinical and therapeutic orientation. In the early years of his research, Lennert used flat wooden boxes for storing the cases, like the one shown here. The 124 slides archived in our box belong to sixteen different patients, or cases, from the years 1946 to 1952. All of the patients were suffering from a disease that was known at the time as ‘retothel sarcoma’. This diagnostic term is no longer in use today, because it refers to a group of diseases that are nowadays differentiated – although all of them show a similar course in that they are aggressive, rapidly progressing types of malignant lymphoma. They are similar, then, without being identical. Classifying diseases histologically means searching for hardly detectable patterns and cutting demarcations into an ocean of possible variations of appearance. Sorting slides in a box can be a subtle and quite complex epistemic endeavour.

The Emergence of the Microscopic View and its Material Environment

Although microscopes had been available since the seventeenth century, they did not begin to play a role in medical research until the middle of the nineteenth century. Various reasons are cited for this delay: the insufficient quality of early microscopes, the lack of experience of the early microscopists, and the lack of a theory that would provide a sound paradigm to substantiate the new visual experiences. An important reason probably lay, however, in a fundamental methodological deficiency and its far-reaching consequences. The French anatomist Xavier Bichat (1771–1802) is considered the founder of histology at the beginning of the nineteenth century. He of all people mistrusted the microscope, and opined that ‘[…] physiology and anatomy, do not seem to me, besides ever to have derived any great assistance [from microscopic instruments], because when we view in an object obscurely, every one sees in his own way, and according as he is affected’ (Bichat 1813: 42). Bichat speaks here of a lack of trans-subjective evidence, and thus of something that is considered essential today for scientific knowledge, namely reproducibility. Once removed, organic tissues undergo rapid decay processes; without fixation, their analysis is a one-time event that cannot be repeated. This deficiency cannot be compensated for in speech or drawings, because what the observer saw always remains subjective – ‘every one sees in [their] own way, and according as [they are] affected’. In short, microscopic specimens of organic tissues, and what they revealed to the eye, were unstable and, consequently, immobile.

Fig. 6.2 Same slide box as above, detail

The microscopic slide as we know it today was not developed until the middle of the nineteenth century. Beginning in the 1830s, Canada balsam was used as an embedding medium; from 1849 glycerine was the favoured substance; ten years later it was gelatine. At the same time, techniques were developed for dehydrating the tissue with alcohol and turpentine, and for embedding tissues in wax, stearin, or gum arabic (Smith 1915: 86 ff). In 1869, the German medical scientist Edwin Klebs published his paraffin-embedding method, the method of embedding tissue that is still the dominant technique in histological lab routine today (Klebs 1869). As Hans-Jörg Rheinberger stresses, only then did the most important condition for a broad application of microscopic methods and their lasting epistemological impact exist: permanence (2005: 71). Klebs’s microscopic slide guaranteed that that which was seen became permanent, making it possible to revise an object, if necessary to re-evaluate what was seen, and to compare the object with older or more recent objects. With a permanent slide, the phenomenon we are looking at is separated from any accidental occurrences when or where it appeared. And this gives it discursive authority.

The microscopists of the time were definitely aware of the significance of this innovation. In 1856, the German anatomist Hermann Welcker stressed the ‘estimable, conclusive’ advantages of permanent slides, and the possibility they provided to ‘be able to show a specific object at any moment’ (1856: 5). Welcker even devoted an entire book to a problem that automatically arose: the ‘storage of microscopic objects’ (1856). A permanent slide that can be archived generates a need for practical and appropriate storage technology. A standard work on scientific microscopy dating to 1860 mentions a commercial producer of slide boxes. Included is an illustration and a description of a slide box exactly resembling ours. In addition to the boxes, the author describes smaller ‘card boxes for holding 24 slides’ or ‘cabinets’ of varying sizes and qualities (Balfour 1860: 36). The announcement by the resourceful salesman is an indication that a microscopic slide culture was rapidly taking root. Microscopic collections proliferated, a development that had other constraints and side effects. The industrial production of glass led to a massive availability of cheaper glass slides. With this, the older variants of specimen holders made of wood or ivory disappeared. Also, standard formats became established. Out of a multiplicity of dimensions, the so-called ‘English format’ of 76 x 26 mm, or 3 x 1 inch, became the standard in Germany. The above-mentioned slide boxes and cabinets of 1860 were already made for this format.

Slide box and slide cabinet, however, also point to different types and contexts of collection. Slide collections grew in large institutions, such as departments of pathology, in the form of teaching collections or case archives. The furniture offered for these collections – ‘a cabinet of Honduras mahogany, capable of holding […] 2000 slides, eleven pounds’ (Balfour 1860: 36) – was recommended for its suitability, durability, and large capacity – and came at a concomitantly formidable price. In contrast to such a centralised, immobile accumulation of slides, to which the actors must go, a handy slide box hints at small collections of individual researchers or ambitious laypersons and their informal get-togethers. The Microscopical Society of London, founded in 1839, was primarily a platform for contact and the exchange of ideas, techniques, and specimens. Above all it was a forum in which the participants took turns to examine a spot on a slide through a microscope (Smith 1915: 88).

The slide box resulted from new technical attributes of microscopic specimens: permanence and archivability. But the slide box is also an indication of a fundamental property of the slide itself, namely that it can be readily mobilised. Bruno Latour (2006) has pointed out the important role of mobile and invariable representations for the distribution of knowledge. Immutable mobiles are crucial parameters when it comes to winning allies and resources. To be sure, slides are not inscriptions on paper in the sense meant by Latour. Slides show the tissue itself – a complex morphological visibility that eludes the abstraction and reduction involved when we write things down. It is this surplus of significance that cannot be expressed exhaustively that makes up the potential of the slide. And it is precisely this that made necessary a universally standardised format for the newly permanent specimens. The slide can be circulated and fitted into various contexts and uses. It is compatible with the infrastructure of the most varied actors. In short, the slide box is the representative of this universal mobility.

Slide Boxes in Karl Lennert’s Collection

Our slide box is only a tiny piece of the puzzle of Karl Lennert’s collection. It belongs to a set totalling 110 slide boxes, known by Lennert as the ‘autopsy archive’, which again is only a part of the total collection. The autopsy archive with its 110 boxes is historically the oldest part of the entire collection. How is it organised? How did Lennert work with it?

Two types of collection have already been mentioned: the teaching collection and the case archive. These types pursue different strategies, but we can still find both in modern pathology departments. Regardless of the fact that the teaching programme is dominated by high-quality photographic reproductions in textbooks, atlases, and Internet platforms, we still have so-called slide series for microscopy courses for students. These are sets of slide boxes, each of which contains a set of identical cases, i.e. slides that were prepared from a single block of tissue. Residents in pathology also train their eyes with the help of small, carefully selected sets of cases in slide boxes that are at the disposal of all pathologists in the department. In addition to these highly selective compilations, every pathology department has an archive. Already, for legal reasons, all analysed cases are archived for at least ten years. For a long time, and to some extent even today, these archives were also used as a reservoir from which suitable cases for a specific research project could be selected as needed.

In Lennert’s collection, both strategies exist in equal measure. Nineteen of the 110 boxes comprise a teaching collection. Each of the nineteen boxes is allocated to an organ system. They contain slides of the most important diseases that can affect the organ. Lennert created this collection for autodidactic purposes. Here we can see that, before specialising, he wanted to master the universal, i.e. the entire scope of histopathology. This includes not only knowledge of the basic types of tissue and their specific pathological deviations, but also knowledge of the optical effect of different staining techniques that highlight the various structures of the tissue. Lennert prepared all of the slides himself; he also wanted to master the histological laboratory technology himself.

The nineteen boxes are numbered, and of course the flat containers were stacked so as to save space. The small sides of the boxes are also labelled, so that they can be read from the side, making the stacked box identifiable. Therefore, only a few steps are required to find a box and a specific slide. The nineteen slide boxes are a kind of compendium of histopathology. With these cases, Lennert learned histomorphological seeing, and on the basis of these teaching files he could calibrate his eyes repeatedly. We do not know how long he used this training tool, although presumably it was only for a few years. At any rate, he was not content with a textbook or with a local departmental collection. He wanted to have his own transportable collection that contained his initial study subjects. This resource accompanied him for his entire professional life. The great majority of Lennert’s boxes, however, are organised in a different way: they contain chronologically filed cases. Our box with the sixteen cases of ‘retothel sarcomas’ is among these. It is one of the oldest; its first case dates to 1946. At this time, there were three boxes and thus three disease categories, one each for myeloid and lymphoid leukemias, and one for lymphomas, all of which were catalogued as reticular sarcomas. Each time a box was filled, a new one was started. The boxes were numbered consecutively. Our box is accordingly designated as ‘ReSa 1’. Thus, the classification of the boxes follows a very simple formula that reflects the nosology and systematic understanding of the late 1940s.

In this case archive, Lennert collected all available cases of the special subject he had chosen: the malignant diseases of the hematopoietic system. The case archive fulfilled two functions, the first of which was that it captured the phenomenal breadth of the subject and therefore formed the material basis for the outstanding expertise in malignant lymph node diseases that the young scientist Karl Lennert had already acquired in the mid-1950s. At the same time, with this stock he created a pool of cases that could be used for the processing of his own research questions. We find individual cases from the collection in Karl Lennert’s publications, and decades later entire case series from the autopsy archive were drawn upon for analyses of aspects of diseases. Here, the epistemological productivity of permanent specimens and their revision becomes evident. An investigation of a slide can always only be based on the historical state of knowledge at a given time. Therefore, a slide always remains subject to general revision, because there are always elements that are not yet foreseeable and not yet recognisable. That is its potential. Diseases, understood as entities – i.e., as clearly defined self-contained and discrete objects – are not natural unchangeable quantities. New laboratory methods, new theoretical insights, and new therapeutic procedures repeatedly challenge an entity. The cases of rare diseases meticulously compiled by Karl Lennert were a reservoir for investigating newly generated questions on the basis of available cases. The slide box is a container of future unanticipated questions, and possibly their answers.

In both parts of the collection (the teaching collection and the case archive) the slide appears as a boundary object that leads from one epistemological context to another. Autopsies, from which all of these cases are derived, are used in the final assessment of a case. The point is to clarify what happened in the body of a patient – and possibly was not recognised during his lifetime. Transferred to the collection, however, the cases served other interests. Here it was no longer a matter of the final clarification of a specific case, but of the disease itself.

The two parts of the collection point to two different strategies for comprehending a disease. Teaching collections represent the entire field of relevant phenomena. Their intelligible reference point is the prototype of a disease; their actual material objects are carefully selected examples of a category that show prototypical qualities (Daston and Galison 2007). Typically enough, the slides in Lennert’s teaching collection no longer have registration numbers. Hence all references to the patient, his or her case history and its documentation are cut off. In these cases the slide is merely a signifier. It shows a sarcoma, a metastasis, etc. Antetypes don’t have a history. The case archive, in contrast, is a complete chronological registration of all relevant incoming cases. This strategy comprehends the disease as a spectrum of infinitely different variants, forms and stages. The two strategies, to identify the prototypic and to comprehend the variance, complement each other and are mutually dependent in the definition of an entity.

The consecutive registration of all relevant cases also has another effect, however. It virtually provokes disturbances, borderline cases that do not fit into the categories, ones that lie crosswise to their boundaries and thus undermine the organised structure. The established order of diseases represented by antetypes in the teaching collection and by the categorical structure of boxes in the archive are here undermined. The scruples and doubts of classification in the daily routine of diagnosis become evident, generating new questions and research projects. Precisely here, the limits of the box are evident. In the autopsy archive the slide boxes demonstrated their advantages. As a standard tool in pathology, they were inexpensive and available. They were also mobile – both spatially-logistically and epistemologically – because as a classification in material form they can be adapted to the most varied contexts. It is only when we try to relate filed cases to each other in a new manner that the slide box proves inflexible.

Slides and Filing Cards

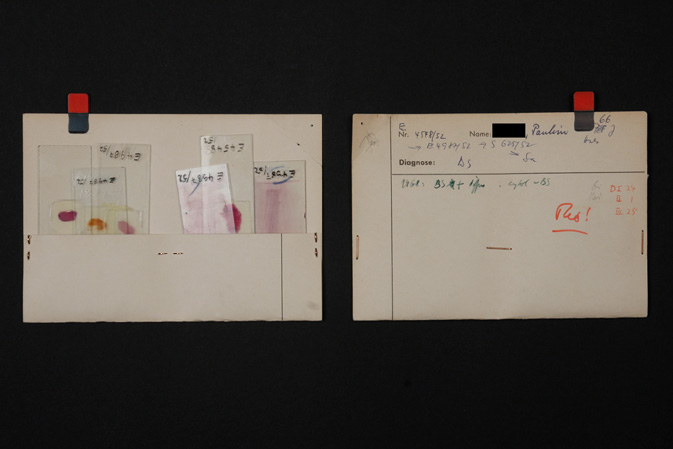

The 110 boxes of the part of the collection entitled ‘autopsy archive’ are, as I have mentioned, the oldest part of Lennert’s collection. In his first years in pathology, Lennert mainly examined material from autopsies. A few years later, he moved to a different department and there he took on a new main responsibility: the diagnosis of biopsy specimens of hematological diseases. These examinations concerned living patients from whom a tissue sample was taken in order to obtain insights into the disease from which they were suffering. Here too, he collected interesting cases, but the slides were no longer deposited in classical slide boxes. Now he deposited the slides in small paper pouches that consisted of a filing card folded and fastened with three paper clips. This technique created a pocket into which he placed the slides. On the front side there was room for notes.

Fig. 6.3 Filing cards, one of 5,400 bioptic (intravital) cases from the Lennert Collection.

Why this change of filing technique? For a long time, the histological examination of biopsy specimens was a very uncertain undertaking. Misdiagnoses were frequent, particularly in the case of malignant lymphomas. While in an autopsy we are dealing with the end stage of a disease visible in a fully open body, in biopsy specimens it is an early or even initial stage in a tiny piece of tissue. The histological condition is consequently less specific and much more difficult to assess. Not least because of these problems, several biopsies were often carried out at different times. Thus, the revision of an older case was no longer merely an option, but was highly likely to become a necessity. Each time that new tissue from a case arrived, the older slides and the original diagnoses were reassessed. For this, newly prepared slides had to be added to old cases. On the other hand, the revision often resulted in a new diagnosis and thus a change in category. The case changed its place in the structure of the collection.

The central question in Lennert’s professional life became how to improve lymphoma diagnosis, and hence he pursued an issue that began to gain urgency in the 1950s. At that time, the treatment of tumours with x-rays developed into a serious therapeutic option. It became evident that different tumours are differently sensitive to radiation. The more aggressive the progress of the disease, the more sensitive are the cells when exposed to radiation. Moreover, the first cytostatic drugs (in the form of nitrogen mustard and urethane) had become available in the late 1940s. Although the therapeutic results were modest at first, there were now various therapy options. Of course, differentiated treatments required more differentiated diagnoses – the expected course of the disease had to be anticipated prior to planning the treatment. Prognosis is a temporal dimension of the disease, something that is strange to the static snapshots of the histologic slide. But it was exactly these external parameters Lennert that wanted to include; he wanted to assess the degree of malignancy out of the morphologic picture of the tissue sample. To make headway here, Lennert began to follow up on the further clinical course of cases that had previously been examined, and to contextualise them with all relevant data (blood count, treatment, survival time). A filing card provides room for such notices; a box doesn’t. For each slide there is only a single line for notes on the inside of the lid of the box. Only the underlying disease and the case number were included as information.

As lymphomas were systematically investigated, more and more categories were distinguished in the structure of the collection. Lennert separated out new entities and differentiated subtypes. The diseases that are combined under the term ‘Retothel-Sarkom’ in our box already comprise three entities in the so-called Kiel classification of 1974, behind which Lennert was the driving force (Bennett et al. 1974). Today, dozens of types and subtypes are distinguished. The slide box cannot cope with these changing needs and practices. The arrangement in the boxes is fixed. The cases are added consecutively according to an inalterable system. It is just as impossible to prioritise individual cases by means of subcategories as it is to add slides with newly prepared stains. For this, the slides have to be painstakingly taken out of the slots in the boxes and re-sorted.

By contrast, the cardboard pouches arranged in a filing cabinet form a highly mobile experimental system. The cases can be removed and re-sorted, in batches or individually. With a technique employing filing cards, things can be moved around. Gaps can be closed. Room can be made as needed. Moreover, new slides prepared from the likewise-archived tissue blocks using new laboratory methods can be accommodated with the individual cases. The new information gained in the process can be added to the previous notes. In fact, the cases were repeatedly revised over long periods of time, placed in flexible new categories, and related to the newest state of research. The key structural element of the collection now lay in the mobility of all elements and categories, which embodied an open mind for unanticipated things. The filing card pouches form the infrastructure of a research process from which a new classification system emerged. In 1974, the so-called Kiel classification was published. Its categories are clearly recognisable in the collection.

And the box? The box has a quality that the filing card pouches do not have. It is robust and stable; it protects the fragile slides reliably from careless handling. This feature made it indispensable for Karl Lennert throughout his professional life. Lennert’s letters, and the notes on the filing cards, show how, as his scientific reputation grew, he operated in a constantly growing network of scientists and medical practitioners. Whereas all of the cases in the autopsy archive come from the hospital where Lennert was employed, many of the biopsy cases in the filing card pouches came from a great number of German hospitals or from other countries. The slide, as immutable and mobile, is easily compatible with an inexpensive resource that is available everywhere: the post office. As a well-known expert on the diagnosis of lymph nodes, Lennert was often consulted in difficult cases. Colleagues with whom he was acquainted sent him rare or unusual cases. Karl Lennert’s correspondence reveals a lively exchange within the scientific community. Slides were circulated. For transporting these delicate slides by post, miniature slide boxes were used.

But classical slide boxes like ours were also still used. They accompanied Karl Lennert in his luggage when he travelled. There are several such slide boxes with selected slide sets in the collection. They are labelled with the names of large cities and dates – the dates and places of important conferences, workshops or tutorials. Despite the high-quality microphotographs and useful practical projection techniques that were readily available in the 1960s and 1970s and were employed in presentations, the original slides were always at hand. For these scientists, every meeting was an opportunity to discuss findings together under a microscope. The slide was always the most immediate and strongest argument.

And today? Using ultra-high resolution scanners, complete slides can be digitalised. This offers considerable advantages, and some technological enthusiasts assume that in the foreseeable future servers will take the place of the old slide archives. Many pathologists are sceptical, however. They point out that no reproduction technique can transport the optical brilliance, the radiance, and the rich details that an impeccable slide reveals to the eyes under a good microscope. One could say that this may change in time. However, the argument seems rather to confirm that microscope and slide continue to comprise the core elements of the identity of the thinking collective of pathologists. These instruments shape not only their daily work, but also their self-conception, and therefore appear indispensable. The slide box will probably still be around for some time.

Acknowledgements

The ideas and context of this essay are the results of an interdisciplinary research project on the biopsy collection of Karl Lennert, a collaboration between the Medical and Pharmaceutical Collections of the University of Kiel and the Kiel Lymph Node Registry. The project was funded by the Volkswagen Foundation.

References

Balfour, J., The Botanist’s Companion: Or Directions for the Use of the Microscope and for the Collection and Preservation of Plants (Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1860).

Bennett, M., et al., ‘Classification of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma’, Lancet, 304.7877 (1974): 405–08.

Bichat, X., A Treatise on the Membranes in General: And on Different Membranes in Particular (Boston: Cummings and Hilliard, 1813).

Daston, L., and P. Galison, Objektivität (Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 2007).

Fleck, L., Entstehung und Entwicklung einer wissenschaftlichen Tatsache [1935] (Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 1980).

Klebs, E., ‘Die Einschmelzungs-Methode, ein Beitrag zur mikroskopischen Technik, Archiv für mikroskopische Anatomie, 5.1 (1869): 164–66.

Latour, B., ‘Drawing Things Together: Die Macht der unveränderlich mobilen Elemente’, in A. Belliger and D. J. Krieger, eds, ANThology, Ein einführendes Handbuch zur Akteur-Netzwerk-Theorie (Bielefeld: transcript, 2006), pp. 259–308.

Rheinberger, H. J., ‘Epistemologica: Präparate’, in: A. te Heesen and P. Lutz, eds, Dingwelten. Das Museum als Erkenntnisort (Köln, Weimar, Wien: Böhlau, 2005), pp. 65–75.

Smith, G. M., ‘The Development of Botanical Microtechnique’, Transactions of the American Microscopical Society, 34.2 (1915): 71–129.

Welcker, H., Ueber Aufbewahrung mikroskopischer Objecte nebst Mittheilungen über das Mikroskop und dessen Zubehör (Giessen: Ricker, 1856).

Willis, R. A., Pathology of Tumours (London: Butterworth & Co., 1948).