17

‘As Modern As Tomorrow’: The Medicine Cabinet

Deanna Day

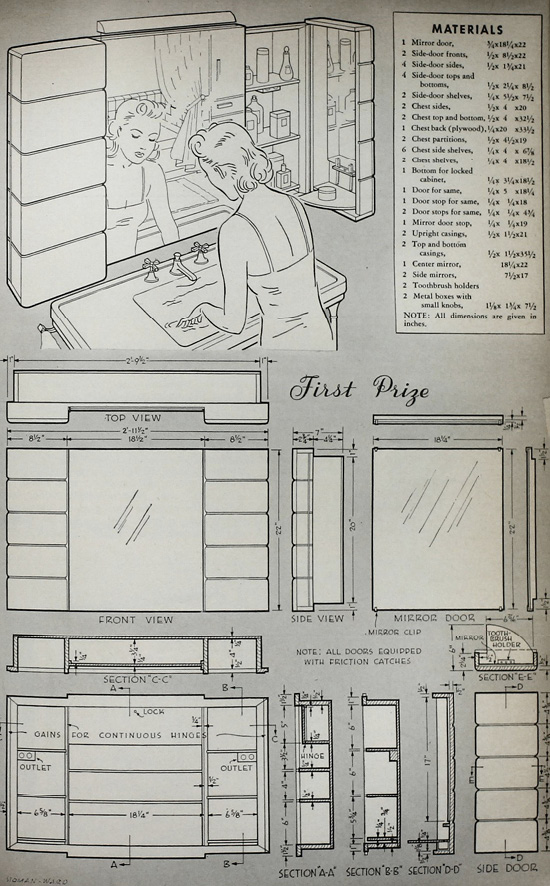

Fig. 17.1 First prize medicine cabinet designed by S. C. Carpenter in Cleveland, Ohio (source: ‘Medicine Cabinet Contest Winners’, Popular Science Monthly (Anonymous 1941: 147))

Box: medicine cabinet. Shape: rectangular. Colour: white and chrome. Distribution: every American home. Habitat: the bathroom. Behaviour: camouflaging, hoarding, and domesticating. Special features: illumination and mirrors. Social relationships: intimate and prescriptive.

Keywords: categorising, hiding, organising, instructing

In the early 1930s, 10,000 New York City families were part of a study conducted by the Office of the Commissioner of Accounts on the status of their home medicine cabinets. The report collected data about what kinds of drugs, devices, and other health care products the ‘average’ family kept on hand for ‘first-aid treatment’. It came to a troubling conclusion: the average home medicine cabinet – the first line of defence in the protection of the family – was shockingly ill-stocked. It was full of outdated medicines and drugs that could cause terrible side effects. Furthermore, it was usually missing several items that the report considered to be absolutely necessary (Palmer 1936: 1–3).

In response, the Consumers’ Project of the United States Department of Labor commissioned a bulletin to educate families about proper home health care. It began, ‘The average medicine cabinet presents a formidable array of bottles, jars, and boxes. The crowded shelves may look like a miniature drug store, but still may not have on them those remedies which are best or most frequently needed for first-aid treatment in the home’. Especially problematic, the bulletin continued, was the fact that the contents of the average medicine cabinet were based on ‘commonly held ideas’ about best health care practices that were ‘not based on sound medical facts’. The bulletin was meant to address this situation by providing families with a list of sixteen necessary items, which included drugs like pain relievers and burn applications, tools like hot water bottles and tooth brushes, and surgical devices like scissors and tweezers (Palmer 1936: 1–3).

In this instance, ‘the home medicine cabinet’ is two kinds of box. First, it is a literal box – the cabinet is the container that holds all of the consumer medical products and devices that the family needs. It keeps them close at hand, collected together, and easy to find, but it also appropriately hides them away, for reasons of both safety and propriety. But it is also another kind of box, for ‘the medicine cabinet’ is as much an ontological category as it is a physical reality. When the Consumers’ Project made this list of the contents of their ideal cabinet, they were collecting and cataloguing a certain kind of health care object: small, intimate technologies of the body. In the process of doing so, they also attached a particular set of social meanings and expectations to these technologies.

In this chapter I argue that the physical reality of the medicine cabinet helped to both create and mirror Americans’ ideas about health, hygiene, the body, and bodily maintenance during the course of the twentieth century. With a new set of objects – tools that belong in the medicine cabinet – there also came a new kind of person who was meant to be the steward and wielder of these tools. Casting ‘the medicine cabinet’ as an ontological category forces us to ask a new set of questions. Why was it created? Who uses it? Who benefits from it? What does it obscure? Answering these questions will help us to start piecing together a patient-oriented history of medicine at the turn of the century, with implications that continue to reverberate today.

Medicine Cabinet as Miniature Drug Store

The cultural narrative of the medicine cabinet is almost entirely one of medical consumerism, a consumerism that was also part of broader efforts to create a new kind of American citizen, both bodily and domestically (Leach 1994). The Consumers’ Project report on the home medicine cabinet literally called the cabinet a ‘miniature drug store’. Moreover, this consumerist impulse is often cast as technologically and scientifically determined. But it may be useful, and more nuanced, to think about the medicine cabinet not as just another set of shelves for household objects, but as something more akin (both literally and symbolically) to the doctor’s black bag. This was the period in which physicians were professionalising and taking control of the practice of medicine. But although unacknowledged, twentieth- (and twenty-first-) century American patients have also been scientific medical workers, and the medicine cabinet has held their tools.

In the majority of the literature in the history of medicine, scholars have most often focused on professionals – physicians, surgeons, nurses, etc. – as they form communities, set standards for education and practices, and gatekeep to keep others out of their domain (Stevens 1999; Porter 1999; Starr 1984; Rosenberg 1995; Melosh 1982). Scholarship on patients, then, often focuses on patients’ interactions with professionals: how they are compliant, or not; how their voices are heard or silenced; or how a patient’s subjective experience of her body is at odds with the physicians’ opinion. But patients also manage their health care without professional intervention: the times that they self-diagnose and self-treat, often relying on family members, friends, and other non-professional support networks. As a practical means, I argue this by focusing on the technology that they use, deploying a broad definition of technology that includes items like thermometers and blood pressure cuffs, but also pharmaceuticals, hot water bottles, bandages, toothbrushes.

The medicine cabinet, as both the place where these objects live and the ontological category from which they operate, does important, unexamined work in structuring this labour. What’s more, the medicine cabinet is a crucial node in a sociotechnical network that often operates to obscure this labour in favour of a consumerist approach. The medicine cabinet materially reinforces the rhetorical and economic ways in which patients are cast as consumers, placing home-based medical care – and those who perform it – firmly within the realm of the private and the commodified. But if we can think outside of this narrative, and focus instead on the object in use, we can see the ways that patients work: how they create knowledge about their bodies, figuring out how they work, and what they should be.

Moving the Medical Box

Several scholars have examined a phenomenon related to the medicine cabinet, namely, the turn-of-the-century travelling medicine chest. Particularly present in the literature are the Tabloid brand medicine chests, manufactured by Burroughs Wellcome & Co. These portable chests were designed to be used in Britain’s tropical colonies, in an explicit effort to bring modern, Western scientific medicine to areas of the world perceived to be in need of the benefits of white European culture. However, as Ryan Johnson has shown, these chests were often little more than a repackaging of centuries-old medicines, bandages, and tools. The modernity of Tabloid medicine chests was, in fact, largely about the chest itself and its categorical functions; as the box gathered certain items together, named and labelled them, and then stamped them with a trademarked brand, it stabilised and then standardised the particular medical practices and authority of its users. Whether or not the medicines inside were themselves modern hardly mattered – their organisation and their use was (Johnson 2008).

At the same time that the Tabloid medicine chest was making its way from Britain to her tropical colonies, domestic medicines were beginning to make a similar move from the kitchen cupboard to the bathroom cabinet. Like the Tabloid chests, the early twentieth-century medicine cabinet collected and organised health care aids, but it also broadcast its own set of requirements and expectations. From its location to its size, the medicine cabinet dictated when, where, and how it should be used. As the medicine cabinet became a standard American household fixture, it was crucial in the process of solidifying cultural standards around home medical practice – standards of hygiene, morality, privacy, and gender (see, for example, Hoy 1996; Ogle 2000; Kline 2000; Cowan 1983; Moskowitz 2008).

Prior to the twentieth century, medicine chests, cupboards, and shelves of various kinds were quite common, but they little resembled the bathroom medicine cabinet we are familiar with today. For centuries, women were the primary providers of care for their families’ health needs, and their medicinal products and tools were stored in the logical place, given the material constraints that were involved: the kitchen. The majority of medicinal remedies were mixed at home, using domestic recipe books that included remedies alongside recipes for meals and other household prescriptions. These recipes often utilised ingredients that would be found in the home kitchen and required the use of tools that would also be found there. Additionally, the location of domestic medicine in the family kitchen is consistent with pre-bacteriological ideas about health. When maintaining bodily harmony was part of an integrated system of care that also holistically included elements like diet, the logic of keeping medicines in the kitchen was obvious (Porter 1999; Vogel and Rosenberg 1979).

But at the turn of the century, medicine experienced a number of dramatic changes that were mirrored in the ways that lay individuals managed their health care at home. With the germ theory of disease, the professionalisation of medical care providers, and the invention of a score of new diagnostic medical technologies, the practice of medicine was becoming a more reductionist, standardised, and expert-driven affair (Bynum 1994; Warner 1997; Howell 1996). Furthermore, patients did not only experience these changes when they visited their physicians – they also experienced marked changes in the realm of at-home, non-expert care, where lay individuals began to perform increasingly scientific medical work themselves.

The move of the medicine chest from the kitchen to the bathroom wall occurred at the same time that individuals were expected to stop making remedies themselves and start using new antiseptics, professionally manufactured pain relievers, and scientific diagnostic tools like thermometers. Crucially, this change in use was predicated upon those users sharing a new scientific epistemology of the body. They had to believe a new idea in medicine at the turn of the century: that human bodies were standardised, and the same medicines would work equivalently on all. They had to believe, for example, that there was a shared normal body temperature, and that deviations from the norm meant ill health, not simple idiosyncrasy. This was a radical shift in understanding the body and using these kinds of medical technologies – the things found in the medicine cabinet – was one of the ways patients came to create this understanding for themselves. In other words, the new ontological category of the medicine cabinet was co-constituted with a new epistemology of the body that was itself created by the scientific labour of both domestic and professional users.

The location of this work was a key component in the construction of its meaning. At the turn of the century, Progressive Era reforms brought a scientific, rationalised, and professional approach to all kinds of endeavours, including indoor plumbing. One of the results was the modern bathroom: efficient and discrete. When new home plumbing systems were combined with late-nineteenth-century public health innovations like city sewage systems, the twentieth-century bathroom became the preeminent hygienic home health management space. While the standard late-nineteenth-century bathroom generally only housed a bathtub, sink, and toilet, twentieth-century bathrooms expanded to incorporate fixtures like foot baths, showers, towel racks, cup holders, and planned lighting fixtures – all in the name of improved sanitation, household management, and efficiency (Hoy 1996).

Medicine Cabinet as Mother’s Tool Kit

These changes were part and parcel of another sweeping change occurring in the United States during the Progressive Era: a widespread consensus gathering around the notion of a national, consumerist standard of living. Historian Marina Moskowitz has described how during the early decades of the twentieth century new national distribution systems for manufactured goods combined with a new advertising and advocacy infrastructure to create a particular aspirational standard of living that embodied progressive ideals in consumer products (Moskowitz 2008).

But while Moskowitz’s account develops in detail the ways that middle-class living spaces (including bathrooms) became part of the advertised iconography of the American home, what is missing are the ways that lay individuals actually utilised them; this is the crucial missing piece for understanding the domestic labour of American medicine. Patent applications and advertisements notwithstanding, historical evidence for daily practices inside the home is often difficult to find. However, I will now examine two evocative examples that suggest the contours of real-life medicine cabinet use, showing the ways that individuals maintained, used, and organised them: a short story by James Thurber, and reporting on medicine cabinets in the pages of the magazine Popular Science Monthly.

Thurber’s short story, titled ‘Nine Needles’, was published in The New Yorker in 1936. After a brief introduction to set the scene, his narrator, who is shaving in the bathroom of his good friends’ home, begins his diatribe about the medicine cabinet:

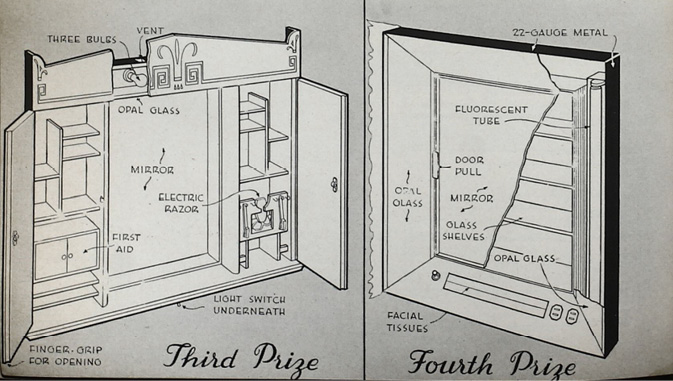

Fig. 17.2 Third prize medicine cabinet designed by John W. Knobel in Ozone Park, New York. Fourth prize medicine cabinet designed by Marvin J. Neivert in Lawrence, New York (source: ‘Medicine Cabinet Contest Winners’, Popular Science Monthly (Anonymous 1941: 148))

I am sure that many a husband has wanted to wrench the family medicine cabinet off the wall and throw it out of the window, if only because the average medicine cabinet is so filled with mysterious bottles and unidentifiable objects of all kinds that it is a source of constant bewilderment and exasperation to the American male […] It may be that the American habit of saving everything and never throwing anything away, even empty bottles, causes the domestic medicine cabinet to become as cluttered in its small way as the American attic becomes cluttered in a major way. I have encountered few medicine cabinets in this country which were not pack-jammed with something between a hundred and fifty and two hundred different items, from dental floss to boracic acid, from razor blades to sodium perborate, from adhesive tape to coconut oil. (Thurber 1936: 17)

The rest of the story is concerned with this protagonist’s frustrations when, after opening the cabinet, nine sewing needles fall into the sink. He attempts to retrieve them using all kinds of objects that repeatedly hit him as they cascade out of the cabinet, including a toothbrush, iodine, and lipstick.

What is telling about this story is the way that the comedy would have depended utterly on the trope (still familiar to us today) of the ludicrously overstuffed medicine cabinet – the situation Thurber creates is acutely funny precisely because of its relatability. Yet despite the situational comedy, none of the items on their own would have seemed particularly out of place; the razors, the adhesive tape, the sewing needles, and the toothbrush are the small-scale equivalents of the household fixtures that Moskowitz describes. They fit comfortably within the class of consumer goods that embody the nebulous cultural values of health and hygiene, and they contribute in specific ways to the maintenance of proper modern bodies.

The story is also a compelling case because of the way it specifically paints the American man as the person frustrated by the medicine cabinet. The narrator/protagonist experiences this assemblage of goods as somehow more upsetting or confusing than he imagines the American woman might be expected to. This framing is initially peculiar, in that the objects which fall out of the cabinet in the story (e.g. razors, bandages, toothbrushes, etc.) are generally not ones that have been culturally coded as specifically feminine. But what the narration makes clear is that what has been coded as female is the category of the medicine cabinet.

While scholars have long explored the domestic sphere as the palette for American women’s consumerist expression, the private space of the medicine cabinet resists these characterisations. Its intimate position as a closed space within the already private space of the bathroom makes it a far less attractive canvas for displaying one’s purchased goods. The role of the cabinet is clearer when we see it not as just a container for consumables, but as a place where work tools are categorised and housed, where the work in question is domestic medical stewardship. The woman of the house is presumably the one who gathers, organises, and is in charge of the tools of home body work. What Thurber’s story illustrates is the extent to which the American medicine cabinet has demanded the attentive work of these female family members – one of the reasons why the overflowing medicine cabinet trope has proliferated so widely is precisely that we know it needs careful maintenance in order to work properly. Consequently, it is the women of the house who are blamed when it does not.

In the Consumers’ Project Report discussed earlier, there is another example of the trope of the poorly stocked medicine cabinet, but in this case the narrative is a much more serious and cautionary one. The story begins with the tale of a small boy running into the family home with a badly scratched knee. When he arrives inside for help there is no antiseptic to be found in the medicine cabinet. There is, however, a two-year-old bottle of cough medicine readily (and uselessly) at hand (Palmer 1936).

The boy’s mother knew that maintaining the family medicine cabinet was a crucial responsibility, but it was also a complicated and time consuming one. The report makes it clear that the mothers of America were felt to be in need of expert instruction on the subject.

Although the explicit purpose of the report is concerned with consumption – it is literally a guide of things to buy and have on hand – practically it reads far more like a training manual, communicating to the non-expert the practical knowledge of professionals about what kinds of medicines to use, and how. It not only contains explicit details about products and brands, but also step-by-step instructions on when and how to use them in order to be the most capable and responsible parent possible. Being proficient in the use of the medicine cabinet was considered to be a crucial step in the moulding of a healthy family.

According to Moskowitz, engineering the family home – or, more exactly, the house – was a further, and explicit, way in which this virtuous ideal was perpetuated. She writes

At the heart of the organization of middle-class spaces, whether domestic or public, was a belief in environmental determinism, that the material world not only reflected the status of those who lived in it, but could in fact help shape that status. […] Objects and spaces were freighted with, and thus carried, significant values of middle-class life, such as the importance of etiquette and social codes, privacy and interiority, investment, and careful management. (Moskowitz 2008: 18)

Or, as one advertisement for Kohler put it, ‘There is one room in every home which is the key to the real standards of living of that household […] [the bathroom] reflects your sense of refinement, your ideals of hygiene and sanitation’. It is, the ad goes on, a matter of pride.

This sentiment also seems to go beyond mere consumerism, even an American consumerism that has been inextricably tied up in citizenship, social values, and belonging (Cohen 2003).

There is a strong engineering and management ethos in Moskowitz’s description of the environment of the home; for a certain class of post-war Americans, an ideal material world not only displayed their social position but also played a role in creating it. Objects and spaces were seen to be so powerful in affecting the lives of their users and inhabitants that citizens needed to be active in managing the materiality of their lives.

The Architectural and the Ontological

Reports from official government agencies were not the only places where lay individuals were taught how to scientifically manage their homes and medicine cabinets (Apple 1995; Cowan 1983). In 1925, approximately a decade before the Consumer’s Project report, Popular Science Monthly published an article titled ‘First Aid For Your Family’. Written by Dr. John F. Anderson, former Director of the Hygienic Laboratory of the U.S. Public Service, the article focuses explicitly on both the design and the contents of medicine cabinets: ‘The household medicine cabinet should be the best lighted part of the bathroom, and so placed that when the mirror-fronted door is open, a light shines full upon its contents. It should be painted and kept in spotless white, and its shelves should be of glass’. Instructions for supplying the cabinet were also provided (Anderson 1925).

Anderson incorporated explicit scare tactics into his appeal for proper medicine cabinet management. The subheadline to the article reads ‘What you should keep in your medicine cabinet for every emergency – How to safeguard against mistakes’, and Anderson warns of the possibility of mistaking a dangerous drug for a harmless one in an unorganised or poorly lit cabinet. Furthermore, he chastises readers against keeping items in the cabinet of which the family physician ‘would not approve’, emphasising that the medicine cabinet was no mere storage device. The article communicates the clear hierarchy of expertise that was embedded in the medicine cabinet. By labelling this collection of hygienic, health-related objects as explicitly medical, physicians and technology producers were able to claim authority over their deployment, which they then communicated to users. In response, as lay individuals began to incorporate their advice and tools into their intimate lives, they also adopted the impulse to properly (i.e. scientifically) manage their tools and their bodies.

Readers of Anderson’s article may have recognised and enacted this impulse in a contest held by the same publication sixteen years later. In 1941, Popular Science Monthly held a contest for readers to design the ideal bathroom medicine cabinet. The contest was incredibly popular by the magazine’s own standards: five prizes (one more than originally planned) and twenty-two honourable mentions were awarded, and the five winning medicine cabinets were featured in a full spread in the magazine. The article was accompanied by stylised representations as well as schematic design drawings of the winners, and it included descriptions and explicit encouragement for readers to attempt to build the cabinets for themselves. The magazine supplied a special award for a contest entrant who actually built their proposed cabinet (Anonymous 1941).

The features of the submitted cabinets give us a sense of how individuals were using their home medicine cabinets by showing us how they wished they could improve that use. For instance, the most highly desired innovations among contest participants were interior as well as exterior mirrors, followed by doors, shelves, and drawers that would maximise the usefulness of those mirrors. Designers also wanted more shelf space, more lighting, electrical outlets, and specialised holders and containers for devices like scissors, tweezers, and tissues. The winning entry also had additional ‘his’ and ‘hers’ shelves on either side of the main cabinet in order to eliminate gender conflict over space for items specifically designed for personal grooming. Runner-up medicine cabinets had even more specialised containment innovations: sterile drawers for first-aid supplies, shelves with different shapes for a multitude of bottles and jars, compartments designed especially for electric razors, etc. One design even included a special locked compartment for ‘dangerous drugs’, implicitly recognising that ‘toilet items’ and medical supplies belonged in the same physical and ontological space, and that in order to share this space effectively they had to be quite carefully managed.

Far from reading like a lifestyle magazine or a shopping guide, this report of this contest clearly portrays the medicine cabinet as a utilitarian object that its users wished to scientifically master. They showed a keen awareness for the values embedded in the object – clean lines, hygienic sterility, efficient organisation, and targeted clarity – that were in turn transferred to the tools within it and the bodies that those tools altered. According to the headline, the winning cabinet was ‘as modern as tomorrow’; so, too, would be the people that it helped create.

Coda: Organisation and Erasure

If the cultural narrative of the medicine cabinet has worked to obscure the work that patients do – and by doing so has excluded patients’ work from crucial discussions about the structure and nature of health care – this chapter must ask one final question. If the ontological category of the medicine cabinet captures a certain kind of small, intimate technology of the body, what does the existence of this category imply about seemingly similar objects that do not belong in that box? This volume discusses at length the processes of making boxes, moving boxes, and putting things into boxes, but what we often overlook are the items – and therefore the identities – that are excluded from our categorisations and collections.

For her cultural history of menstruation, historian Lara Freidenfelds interviewed a number of women about their mid-twentieth-century menstrual practices (2009). These women recounted to her that during their youth, the commonly accepted place for storing menstrual products was not the bathroom, but the bedroom; such products were generally hidden under their beds, or sometimes tucked away in the corners of their closets. The bathroom medicine cabinet was considered to be far too public a place to store such intimate objects. This exclusion raises important questions about our cultural relationship with menstruation. Is it too dirty, too untoward for the medicine cabinet? Were (and are) the cycles and fluctuations of women’s bodies too chaotic and messy for the hyper-rational, hyper-sanitised medicine cabinet? This relegation of menstrual technologies to the even more private (yet less culturally hygienic) space of the bedroom reveals the embarrassment that the women interviewed were meant to feel about their unruly bodies. Even in the domain of intimate health and body work of which women were the family stewards, each woman experienced her period alone.

In Freidenfelds’ account, it was not until the emergence of another common bathroom storage innovation, the under-the-sink storage cabinet, that her interviewees felt comfortable storing menstrual products in the family bathroom (2009: 146–50). If we consider seriously what the medicine cabinet does as it orders, rationalises, and makes appropriate a very specific and ultimately limited kind of body work, we can see the ways that it contains, hides, tells stories about, and ultimately devalues that work and the bodies of those who perform it.

References

Anderson, J. F., ‘First Aid for Your Family’, Popular Science Monthly, February 1925.

Anonymous, ‘Prize-Winning Medicine Cabinet’, Popular Science Monthly, May 1941.

Apple, R. D., ‘Constructing Mothers: Scientific Motherhood in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries’, Social History of Medicine, 8. 2 (1 August 1995): 161–78.

Bynum, W. F., Science and the Practice of Medicine in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

Cohen, L., A Consumer’s Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America (New York, NY: Knopf, 2003).

Cowan, R. S., More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1983).

Freidenfelds, L., The Modern Period: Menstruation in Twentieth-Century America (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009).

Howell, J. D., Technology in the Hospital: Transforming Patient Care in the Early Twentieth Century (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996).

Hoy, S., Chasing Dirt: The American Pursuit of Cleanliness (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1996).

Johnson, R., ‘Tabloid Brand Medicine Chests: Selling Health and Hygiene for the British Tropical Colonies’, Science as Culture, 17.3 (2008): 249–68.

Kline, R., Consumers in the Country: Technology and Social Change in Rural America (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000).

Leach, William R., Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture (New York, NY: Vintage, 1994).

Melosh, B., The Physician’s Hand: Nurses and Nursing in the Twentieth Century (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1982).

Moskowitz, M., Standard of Living: The Measure of the Middle Class in Modern America (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008).

Ogle, M., All the Modern Conveniences: American Household Plumbing, 1840–1890 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000).

Palmer, R. L., The Home Medicine Cabinet (Washington, D.C.: Consumers’ Project, U.S. Department of Labor, June 1936).

Porter, R., The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1999).

Rosenberg, C., The Care of Strangers: The Rise of America’s Hospital System (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995).

Starr, P., The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1984).

Stevens, R., In Sickness and in Wealth: American Hospitals in the Twentieth Century (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999).

Thurber, J., ‘Nine Needles’, The New Yorker, 25 January 1936.

Vogel, M. J., and C. Rosenberg, eds, The Therapeutic Revolution: Essays in the Social History of American Medicine (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1979).

Warner, J. H., The Therapeutic Perspective: Medical Practice, Knowledge, and Identity in America, 1820–1885 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997).