15

Parcels Render Neglected People Visible

Tanja Hammel

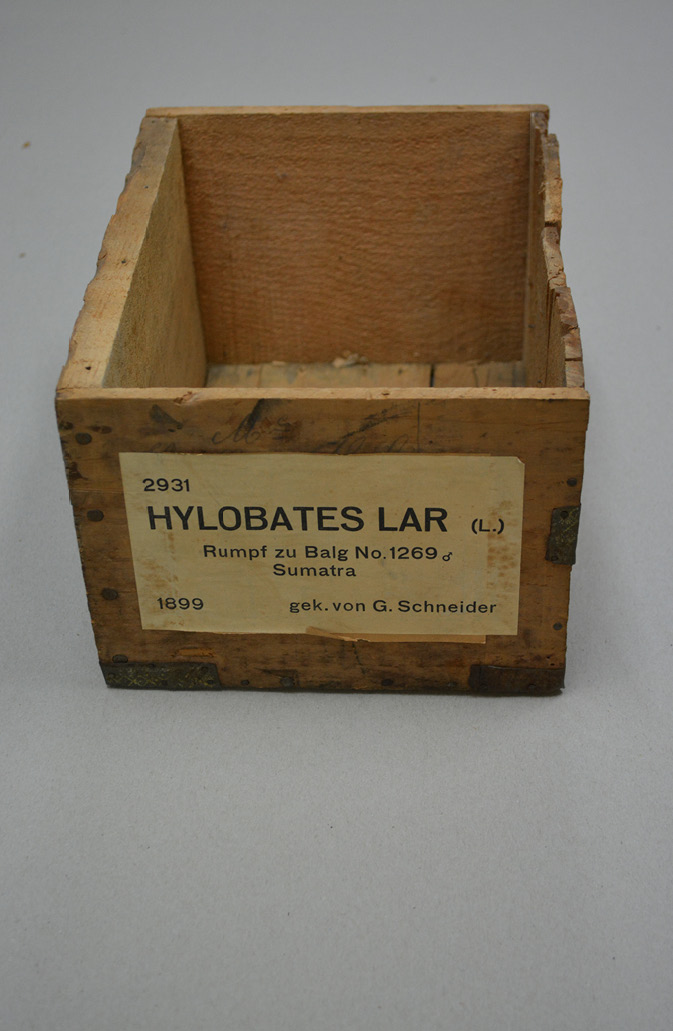

Fig. 15.1 A wooden box from the Natural History Museum – Archives of Life, Basel, Switzerland (source: photographed by Tanja Hammel, 10 September 2014)

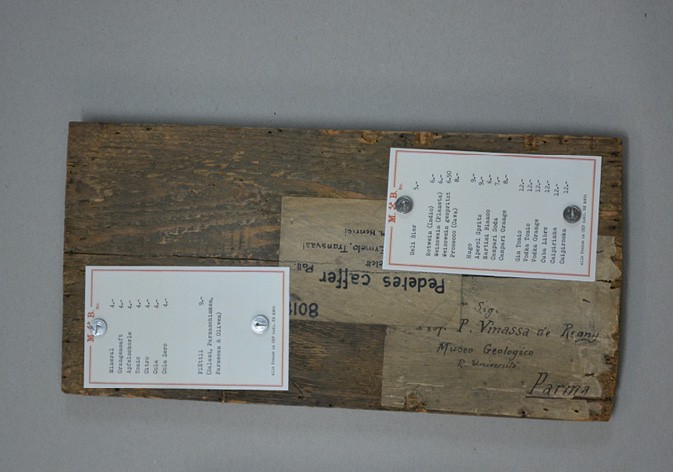

Box: parcel in Natural History. Material: wood or cardboard. Wooden boards of different thickness, from different tree species, and from different points of time, in various colours depending on their materiality and the artefacts or biofacts they transported. Many of them are reused boxes that previously contained goods such as sugar, soap, cigarettes, photo glass plates, etc. Size and shape: one side is about 60 x 30 cm, of rectangular shape. Behaviour: they enveloped, safeguarded, and preserved their content on their journeys from the animals’ natural habitat to the collection or laboratory where their content was researched or prepared for display. They connected sender and receiver over vast distances. Habitat: some endured and are still part of the storing infrastructure of natural history museums or private collections. Others, such as those at the Natural History Museum – Archives of Life, Basel, Switzerland, have been adapted for other purposes. Migration: the accessibility of the material allowed for its use by virtually everyone. On their way, parcels moved through the hands of numerous people, and were in contact with various vehicles – horse-drawn carriages, ox-wagons, and steamboats, for example – and animals – such as the various insect species that damaged them. Collector: Martin Schneider, Geosciences’ Collection Manager at the Natural History Museum – Archives of Life, Basel, Switzerland. The museum was founded in 1821. Schneider and his predecessors have preserved a collection of boxes since the late nineteenth century and stored them in three large cardboard boxes. Status: largely intact, some damaged and missing parts; other parts remain but are differently used today. As they were often in use for transport until it became impossible, hardly any ephemeral cardboard parcel has been preserved. Where scraps remain, they can provide interesting information such as addresses, collectors’ names, and the tags added later to store specimens. Boxing principle: opening up, rendering visible, connecting, providing, enriching.

Keywords: containing, compressing, concealing, circulating, shipping, re-using, networking, recycling, abducting, assembling, combining, interlacing, rendering companion species visible

This parcel (Figure 15.1) was used to transport part of a lar-gibbon’s skeleton from Sumatra to Basel. The content was part of German-born Gustav Schneider’s (1834–1900) collection. Schneider was conservator of the natural history collection in Basel, Switzerland, from 1859 to 1875. At the same time, he traded specimens to make a living. He accumulated a rich collection that he sold to museums. Specimen dealing was much more lucrative than working at the museum, which is why he made this his main profession. He also acted as a taxidermist of the specimens he sold (see Schneider 1900).

Going through exhibitions at natural history museums such as those in Basel, visitors encounter white male Europeans as the sole actors in the field of natural history. But if curators attended to the routes by which the parcels arrived at the museums, and how the material on display was packed and transported, this narrative cannot persist. Focusing on parcels and their human companions, this article shows how parcels shed light on men and women collectors, both colonial and indigenous, who have hitherto been marginalised.

Due to the ephemeral nature of their material, we do not find many parcels from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in collections. Being part of everyday transport infrastructure, parcels as such were not considered noteworthy, and this is why there are hardly any illustrations depicting them. But parcels were nevertheless of vital importance in knowledge circulation. A scientist’s or an institution’s status increased with the number of parcels received. Parcels caused excitement among metropolitan naturalists, but also fear lest the contents be damaged or fail to reach the addressee. The boxes’ content was, for metropolitan and, later, colonial urban naturalists, an intricate link between their laboratories and the ‘field’ in the wider world. This content provided metropolitan naturalists with evidence for taxonomy and theories, for example, for species’ distribution and evolution by natural and sexual selection. Darwin’s correspondence, for instance, is full of references to lost parcels, stolen manuscripts and specimens, and the resulting detailed, almost paranoid, enquiry about the whereabouts of parcels. In one hundred and fourteen letters to and from Darwin between 1828 and 1881, parcels are mentioned. Darwin always ‘anxiously […] hope[d] to hear that the parcel is safe’, and was so concerned that he asked his correspondents to send parcels to his brother in London, not his home in the Kent countryside, where he feared it would get lost (Darwin to Japetus Steenstrup, 30 December 1849). He was ‘much obliged for a single line to acknowledge’ a parcel’s ‘receipt’ (Darwin to J. F. W. Herschel, 7 May 1848), and when manuscripts were dispatched he asked his colleagues to inform him ‘when [the] parcel is sent off’ (Darwin to James Crichton-Browne, 31 January 1870). When a parcel’s content was particularly valuable, he would send his servant in the tax-cart to pick it up (Darwin to J. D. Hooker, 19 July 1855, 30 December 1849; to Sowerby, 11 November 1850).

Parcels are companions, and have life forces. Let us extend Donna Haraway’s concept of ‘companion species’ (Haraway 2003), which she particularly used for dogs, to inanimate beings such as parcels that may shape the scientific or professional person who comes into contact with them as much as the person shapes the parcel. Postcolonial and STS scholars have long debated whether there are different epistemologies or ontologies in different contexts. The main problem has been that for too long STS scholars have seen the world and science through Euro-American eyes. In this context, the nature/culture divide that distinguishes between animate and inanimate entities has determined how scholars think about actors in science. However, in Bantu society, for example, people do not differentiate between objects and persons, but see all animate and inanimate beings as forces of life in interaction (Connell 2007: 97–98). Seen from such a perspective, then, parcels may have ‘life forces’, like their human companions. One such force that is of particular importance here is the power they have to render visible their human companions who have hitherto been neglected because of their belonging to subordinate social groups – whether this subordination was based on ethnicity, gender, or social class.

Parcels render their less visible human companions visible when ‘black-boxing’ fails (see e.g. Endersby 2008: 65, 89–93, 97, 205–08; Musselman Green 2003: 367–92). Black-boxing, according to Bruno Latour, is the process through which aspects of science make themselves invisible when they are successful. When parcels arrive, as Darwin’s letters show, they become opaque and obscure (Latour 1999). Looking for parcels in famous nineteenth-century naturalist’s writings, such as Alfred Russell Wallace’s accounts from the Malay Archipelago, we learn that locals filled parcels with their collected birds of paradise that Wallace then sent to England to become known (Wallace 1862). In Australia, botanists and botanical artists employed men aboriginal ‘guides’ and men and women collectors but did generally not acknowledge them by name. However, there are rare cases such as the herbarium sheets found at the National Herbarium of Victoria in Melbourne, from which we learn that parcels were packed by part-Aboriginal Australians Lucy and Thomas Webb, and Lucy Eades, who had also collected the plants that were career-making for German-born, Australia-based botanist Ferdinand Mueller (Maroske 2014: 74–75, 85). In Europe, volunteers and poorly-paid employees unpacked parcels. Parcels filled with botanical specimens, particularly from the Cape, were transported between Trinity College Dublin and ‘the quay’ on the donkey and cart of Jack Spain, an elderly disabled man (Fischer (ed.) 1869: 215).

Parcels allowed humans to negotiate power. Colonial collectors were aware of naturalists’ dependence on them, and they voiced the need for tools and parcels. In the Cape, the colonial naturalist Mary Elizabeth Barber (1818–1899), for instance, stressed that boxes were ‘not as “plentiful as black-berries” in the country’ (Barber to Trimen, Highlands 15 April 1864); a striking analogy given the local rarity of blackberries. Scientists at urban or metropolitan institutions subsequently provided her with boxes. Metropolitan naturalists preferred colonial collectors who knew little about science and would content themselves with sending specimens. Botanist William Hooker, for instance, encouraged collectors to have their ‘eyes open’, but not to read books, since ‘many of the best collections of plants’ had ‘been made without books’ (1859: 419–20). Colonial collectors who were not content with this metropolitan attitude and aimed to show how important they were sometimes retained parcels to name specimens. George Bentham at Kew Gardens published seven volumes on Australian flora (1863–1878) with the ‘assistance’ of Ferdinand Mueller, who had aimed to do it himself. The only possibility for Bentham to empower himself was to classify plants before sending them to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew (Lucas 2003: 255–81). Hooker’s son and successor, Joseph Dalton, silenced his collectors in New Zealand, William Colenso and Ronald Gunn, in the same way as had his father before him (Endersby 2001: 343–58, Endersby 2009: 74–87). Ferdinand Mueller also silenced his women and autochthonous colleagues and collaborators, sometimes misspelling their names (Maroske, Vaughan 2014: 72–91, 91–172), in a sign that he wished to downplay their work in order to establish his own reputation as more than a collaborator of metropolitan scientists. Since the time of the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) it had been common practice among taxonomists not to acknowledge every individual collector in their studies. When Mueller was accused of ‘plagiarism’ against plant collectors, his Austrian colleague Joseph Armin Knapp defended him, arguing that it was ‘downright absurd’ to ‘demand such a high degree of resignation and self-effacement’ (1877: 597–617). To ensure mutual interchange between colonial and metropolitan naturalists and institutions, exchange societies were established that ensured the swap of specimens between collections worldwide. One example was the South African Botanical Exchange Society, founded in 1866, which aimed to ensure sufficient supply from a large number of amateur botanists. By 1868 approximately 9,000 duplicates had been sent abroad in parcels, and in return specimens from Europe, North America, and Australia entered South African herbaria (Gunn and Codd 1981: 183).

While recent studies have focused on the knowledge British scientists gained in the southern hemisphere, or the vital role autochthonous people’s informal knowledge or collaboration played in the production of knowledge (see e.g. Jacobs 2006, McCalman 2009), parcels allow us to see further. The parcels retained by Australian botanical collections show how colonial naturalists exercised their power and emancipated themselves from British institutions at an earlier point in time than previously thought. The parcels demonstrate the impact people in the south had on the formation of new disciplines that have generally been believed to have emerged in the north. These mundane, ephemeral companion objects allow us to encounter women and men from different social and ethnic backgrounds, their access to parcels, and their impact on science. Museum exhibits would be many fewer, we would know much less about the world’s flora and fauna, and some scientific disciplines may never have emerged without parcels.

The box in the photographs above remains hidden in the natural history museum’s storeroom, enclosed in a cardboard box. Its lid, however, has recently been seen in the museum. The curators used it to decorate menu cards at special events (Figure 15.3).

Fig. 15.2 A cardboard box filled with wooden boxes at the Natural History Museum – Archives of Life, Basel, Switzerland (source: photographed by Tanja Hammel, 10 September 2014)

Fig. 15.3 Menus for ‘After Hours Summer Edition, Chillen im Museum’, 11 September 2014 (source: photographed by Tanja Hammel)

Being used for this purpose, this new artefact raises awareness of the materiality and temporality of museum and science objects. It helps us to visualise the circulation of matter and being. The animal specimens, as well as the trees that the box and paper are made of, evolved over millennia and in distant parts of the world. This new artefact also reveals the museum’s past practice or effect of ‘cutting objects out of specific contexts’ and ‘therefore concealing the relations of power that produced the collection’ (Clifford 1988: 220; Roque 2011: 5) and raises awareness of black-boxing. In fact, it works in the opposite way to black-boxing and purification – scientists’ de-contextualisation of specimens that arrived in parcels to construct ‘pure’ knowledge objects and separation between nature and culture (Latour 1993: 24, 44, 140). It is therefore a significant intervention that the museum now exhibits parts of the parcels and confronts visitors with their life stories. The boxes’ histories had a vital impact on Western knowledge production and discipline building, so rendering them visible should be shortlisted on every (museum, university, archival) collection’s agenda. This would allow us to reflect on the politics of knowledge production, and to take the history of science out of its black box.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the workshop organisers, to the editors and participants, and to Balz Aschwanden, Melanie Boehi, Madeleine Gloor, Michael Schaffner and Christine Winter for their comments.

References

Bentham, G., Flora australiensis: A Description of the Plants of the Australian Territory, assisted by Ferdinand Mueller, 7 vols (London: L. Reeve and Co., 1863–1878).

Clifford, J., The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988).

Connell, R., Southern Theory: The Global Dynamics of Knowledge in Social Science (Cambridge/Malden, MA: Polity 2007).

Darwin, C., Darwin Correspondence Project (http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk), Darwin to J. J. S. Steenstrup, 30 December 1849, Letter 1281; Darwin to J. F. W. Herschel, 7 May 1848, Letter 1173; Darwin to J. D. Hooker, 19 July 1855, Letter 1722; 30 December 1849, Letter 1281; Darwin to J. C. Sowerby, 11 November 1850, Letter 1368; Darwin to James Crichton-Browne, 31 January 1870, Letter 7089

Endersby, J., ‘“From Having no Herbarium”. Local Knowledge vs. Metropolitan Expertise: Joseph Hooker’s Australasian Correspondence with William Colenso and Ronald Gunn’, Pacific Science, 55.4 (2001): 343–58

——, Imperial Nature: Joseph Hooker and the Practices of Victorian Science (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2008).

——, ‘A Gunn and two Hookers. Friendships That Shaped Science’, in: I. McCalman and N. Erskine, eds, In the Wake of the Beagle. Science in the Southern Oceans from the Age of Darwin (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2009), pp. 74–87.

Fischer, L., ed., Memoir of W. H. Harvey, Late Professor of Botany, Trinity College, Dublin: With Selections from His Journal and Correspondence (London: Bell and Daldy, 1869).

Gunn, M., and L. E. Codd, Botanical Exploration in Southern Africa (Cape Town: A. A. Balkema, 1981).

Haraway, D., The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003).

Hooker, W. J., The Article Botany, extracted from the Admiralty Manual of Scientific Enquiry, 3rd edition, 1859: comprising Instruction for the Collection and Preservation of Specimens; together with Notes and Enquiries regarding Botanical and Pharmacological Desiderata (London 1859).

Jacobs, N., ‘The Intimate Politics of Ornithology in Colonial Africa’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 48.3 (2006): 564–603.

Knapp, J. A., ‘Baron Ferdinand von Mueller: Eine biographische Skizze’, Z. Allg. Österr. Apotheker-Vereins, 15.36 (1877): 597–617, trans. by D. Sinkora, 15 January 1977, p. 7, The Library of the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne.

Latour, B., We Have Never Been Modern, trans. by C. Porter (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993).

——, Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999).

Lucas, A. M., ‘Assistance at a Distance: George Bentham, Ferdinand von Mueller and the Production of Flora australiensis’, Archives of Natural History, 30.2 (2003): 255–81.

Maroske, S., ‘“A Taste for Botanic Science”: Ferdinand Mueller’s Female Collectors and the History of Australian Botany’, Muelleria, 32 (2014): 72–91.

Maroske, S., and A. Vaughan, ‘Ferdinand Mueller’s Female Plant Collectors: A Biographical Register’, Muelleria, 32 (2014): 91–172.

McCalman, I., Darwin’s Armada. How Four Voyagers to Australasia Won the Battle for Evolution and Changed the World (Sydney: Simon & Schuster Australia, 2009).

Musselman Green, E., ‘Plant Knowledge at the Cape: A Study in African and European Collaboration’, International Journal of African Historical Studies, 361 (2003): 367–92.

Roque, R., ‘Stories, Skulls, and Colonial Collections’, Configurations, 19.1 (2011): 1–23.

Schneider, G., jr, ‘Gustav Schneider, 1834–1900’, Verhandlungen der Schweizerischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft, 83 (1900), lxxxiv–xciv.

Trimen Correspondence, Royal Entomological Society, St Albans, Naturalist Mary Elizabeth Barber to entomologist Roland Trimen (1840–1916), Box 17, Letter 37, Highlands, 15 April 1864.

Wallace, A. R., ‘Narrative of Search After Birds of Paradise’, Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1862, ed. by C. H. Smith, <http://people.wku.edu/chalres.smith/wallace/S067.htm> [15 September 2014].